Editor in Chief: L. Sabaliūnas

|

www.lituanus.org |

|

Copyright

© 1956 Lithuanian

Students Association, Inc.

October

1956 No.3(8)

Editor in Chief: L. Sabaliūnas |

|

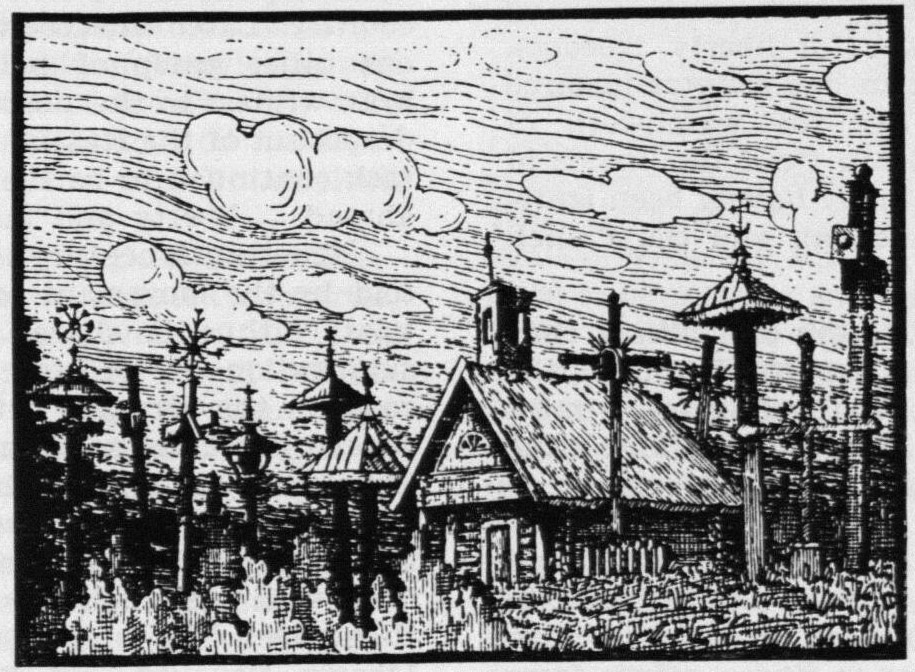

CROSSES

|

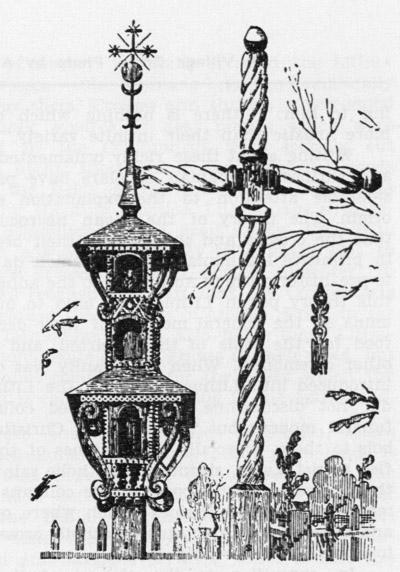

| Crosses near Vilnius. A drawing by A. Jaroševičius |

DR. J. GRINIUS

DR.

JONAS GRINIUS

studied at the University of Kaunas, Grenoble and Paris, taught

literature, history of art and esthetics at the University of Kaunas,

was a staff member of the College of Free Europe at

Strassburg—France and chairman of the Lithuanian group of

that

institution of higher learning. Author of various books and plays; is

active as a critic.

All THE NATIONS of Europe have had their rich folk art but, in many places, the technical advances of civilization have already shoved it out of existence. Lithuania is one of the few European nations which, to this day, have kept alive their folk art. It is especially in her folk-songs and her hand-carved wooden crosses and shrines that this is manifest. The beauty of Lithuanian songs has been praised by German poets and writers since the middle of the 18th century. Lessing, Herder, and Goethe were the first to be fascinated by the originality of these songs. From then on Lithuanian songs began to interest poets, musicians, and scholars of other European nations.

Lithuania's wooden crosses and shrines caught the interest of her southern and western neighbors much later than her songs did. Two Germans — Hermann Struck and Herbert Eulenberger — have vividly described the impression which these abundant monuments of Lithuanian religious and national culture make on the foreigner who is visiting Lithuania for the first time. In Skizzen aus Litauen, Weissrussland und Kurland (1916), written in collaboration, here is what they have to say: "Nowhere in the world, except, perhaps, in Tyrol, are there as many crosses to be seen as in Lithuania. Like ship masts they stand by paths, fields, and crossroads. They are assembled in the cemeteries of Lithuania where, like lofty arid lilies, they grow out of funeral mounds. Bent by time, the tall crosses seem to greet like symbols of the deceased with whom Lithuanians, like no other nation, live in a constantly fearful and friendly contact. They often create an eery atmosphere, especially in winter, when the entire country is covered with a thick layer of snow out of which rise tall black crosses which seem to beckon with one solemn finger. A Lithuanian cemetery indelibly imprints itself on the memory when, in the winter, the silhouettes of these assembled crosses rise to the sky like shadows of Galgota against the red background of the western sunset.

Having seen some photographs of Lithuanian crosses and shrines at the international exhibition at Monza (Italy), Luigi Caglio, an Italian, considered them as follows: "...primitive instinctive creations in whose living current, which spurts forth from the dark and sincere recesses of the genius of the people, one may rejoice." L. Caglio sees in the Lithuanian crosses the most typical expression of folk art in Europe. This opinion agrees with the view expressed by the German, Alfred Brust, who said: "Among them are works of art which, here exposed to all kinds of wind and weather, belong to the simplest and most meaningful rarities of great folk art." The French writer Jean Maucle thought remarkable the variety of form found in these wooden monuments. According to him: "...there is nothing which could be more artistic than their infinite variety."

|

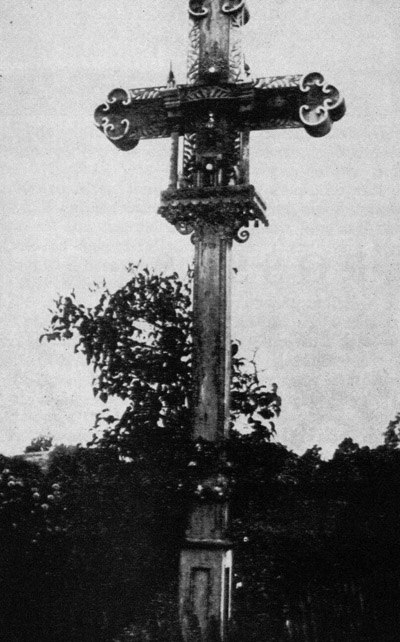

| A

Village Cross. Photo by A. Varnas |

Writing about these richly ornamented crosses and shrines, Lithuanian scholars have paid considerable attention to the explanation of their origin. The theory of the pagan necrocult holds that the crosses and shrines had their beginnings in primitive Lithuanian culture, which dates back to pre-historic times. According to the adherents of this theory pagan Lithuanians used to build columns on the funeral mounds of their dead, leave food for the souls of the departed, and perform other ceremonies. When Christianity was officially introduced into Lithuania (1387), the Lithuanians did not discontinue building roofed columns on funeral mounds but began adding Christian symbols to them, especially little statues of the crucified Christ. Later, statutes of Catholic saints found their place under the roofs of the columns. In this manner developed shrines which where one, two, and three stories high; truly Catholic crosses came into being considerably later.

In opposition to the theory of the pagan necrocult, stand the upholders of the theory of Christian origin. They contend that there are no weighty archeological facts which warrant stating that the wooden crosses and shrines stem from the pagan religion and that the 16th and 17th century documents, which mention prohibitions on the erection of crosses, do not prove anything of consequence. First, these documents speak of neighbors related to Lithuanians—Prussians and Latvians; second they do not indicate the reasons for these prohibitions on the erection of crosses; on the other hand, the sources from which we learned of the paganism of Latvian crosses were issued by Protestant clergymen who, in the 16th and 17th centuries, called any manifestation of the Catholic cult pagan. Even though their forms are original and almost not to be found in any other part of Europe, the adherents of the second theory maintain that the Lithuanian crosses and shrines are of Christian origin. They argue that these numerous and varied wooden monuments arose while Lithuanian nature was being "christianized" — when Christianity was fighting against tree worship which, in the Lithuanian pagan religion, occupied an important place. However, even the authors who uphold the theory of Christian origin admit that some ornaments used on these monuments and even some symbols may have had their beginnings in traditions reaching pre-historic times. Divers ornaments combined with the constructive forms of the cross endow the wooden crosses with a rare originality. To the extent that they testify to the live aesthetic sense of he Lithuanian people, the abundance of crosses and shrines and their Christian symbols disclose the deep faith and devoutness of the Lithuanians (W. Szukiewic).

While the wooden crosses and shrines are most abundant in Lithuania's village and town cemeteries, they are found everywhere: on highways, crossroads, and bridges; in the fields and in the woods, and on farms.

During the first half of the 19th century, so many crosses were erected that, on highways, they were hardly a few hundred feet apart and sometimes only a few tens of feet apart. Therefore, the Polish poet, W. Pol, called one province (Žemaitija — Samogitia) of Lithuania the "holy country of God." This abundance of crosses and shrines endowed the Lithuanian countryside with a specific character which is not encountered in any other part of Europe. Naturally such a landscape could not please the Russians who occupied Lithuania in 1795 and wanted to transform her into an insignificant) province of the Russian empire. Finding a suitable pretext in the revolt of 1863, they doubled the oppression of the Lithuanian people, concentrating especially on the demolition of their culture. An order prohibiting the erection of crosses on soil which was not blessed was issued by the czar's administration. This was supposed to lead to the extinction of wooden crosses and shrines standing on highways and farms. The Lithuanians refused to bow to this barbaric order, however. With foreboding in their sorrowing hearts, they watched the crosses which their grandfathers and fathers had built begin to sway from age; they knew that a few gusts of wind might fell many of them to the ground. Determined not to let their crosses disappear, the people found ways to evade the orders of the Russian administration. "When I was a child," testifies B. Ginet-Pilsudzki, "I often heard my mother and my aunts tell of frequent salvages of crosses. To confound the vigilance of the police who in their exaggerated diligence used to harass peaceful inhabitants, the people ussd to apply a certain color to any cross which was in danger of falling and then make a new cross of the color. Some dark night, with guards posted all around, as silently as possible, they removed the old cross and in its place erected its substitute (alter ego), i.e., the new cross." Thus Lithuanians showed their resistance for over 30 years until, in 1896, the Russian administration repealed its order.

The Lithuanian cross became not only a symbol of the Catholic religion but also a cherished monument of Lithuanian folk art. Lithuanian artists like M. Čiurlionis, A. Žemaitis, A. Varnas began to take the motif found in wooden crosses and shrines and introduce it into their creations. Lithuanian youth organizations began to erect them as witnesses to their activities. Lithuanian emigrants in foreign countries, especially those in the United States, used to and still continue to build crosses near their churches and monasteries and even on their farms as symbols of their native country. In the gardens of the National Museum of War (Kaunas, Lithuania) where various patriotic manifestations frequently took place, there were at the tomb of the unknown soldier a number of original crosses which had been assembled from different parts of Lithuania. When the tenth and the twentieth anniversary of the reconstruction of Lithuania was being celebrated (1928 & 1938, respectively) many towns could find no more fitting way to commemorate this occasion than to erect richly ornamented crosses.

World War II brought about some changes which can best illustrate how these monuments were intertwined with the good and bad fortune of Lithuania. June 15, 1940, the Soviet army invaded Lithuania and imposed on her an unheard of yoke of slavery. It fatally affected the Lithuanian crosses — the Russians began systematically to destroy them. Crosses and shrines which stood near public squares or near houses which were occupied by the Communists were secretly cut down at night; those which stood near the woods and in the fields served the Soviet soldiers as targets for shooting practice. Lithuanians witnessed this demolition with a deep sorrow. Unable to resist in any other way they tried unttll 1951 to erect new crosses wherever posible. However, in 1955 news reached the West that the Communists had forbidded the erection of crosses. True, in far Siberia Lithuanian exiles also build these Lithuanian monuments on the graves of their dead, but that cannot compensate for the losses which the occupant is constantly inflicting in the fatherland.

Besides, the wide expanses of

Siberia, where many

Lithuanians now live, is a foreign land, it is not that Lithuania of

the crosses which the people have defended through the ages and of

which the Italian G. Salvatori wrote in 1925: "Where time the destroyer

has mercilessly demolished and buried everything, these crosses rise

from the soil by the thousands. Where the ruins of a stone castle are a

rare sight, where the wooden houses are rebuilt only once in a hundred

years, there history could not plant in its wake eternal monuments like

in the lands of the pyramids and forums. True, here, too, history has

marched through with a step of iron and fire but in the footsteps of

brave soldiers forests grew up, oats were sown and reaped many times.

Only these wooden crosses, fallen and raised up again, damaged and

renewed every century by the modest carpenter, have a beautiful

significance: they bear witness to the unconquerable will of that small

but great nation which is fighting the deadly plot formed against it by

men and nature. This is why the cross in Lithuania is surrounded by

respect and adoration which we give to the revered remnants of the

marble columns of our Para."

|

| Old cemetery in Lithuania. A drawing by A. Jaroševičius |