Managing Editor P. V. Vygantas

|

www.lituanus.org |

|

Copyright

© 1957 Lithuanian

Students Association, Inc.

March,

1957 No.1(10)

Managing Editor P. V. Vygantas |

|

NATIVE MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS

PROF. JUOZAS ŽILEVIČIUS

JUOZAS

ŽILEVIČIUS, one of the most renowned Lithuanian composers and the

author of several hundreds of musical compositions, has been the Art

Director of the Lithuanian Theater, the director of the Conservatory at

Klaipėda and has been active participant in the field of Lithuanian

music both in Lithuania and the U.S.A.

An idea of the great extent of Lithuania's musical inheritance may be gained from the fact that within the short space of a year the writer has been able to clasify twenty-six distinct types of musical instruments as indigenous to the Lithuanian people. That this work was accomplished with the assistance of over a hundred voluntary co-wcrkers in various parts of that country speaks well for the esteem in which the common people hold their musical heritage.

Before beginning the actual descriptions of these instruments, a few words will be expressed concerning their various origins. Some of these instruments are undoubtedly indigenous to the country and cannot be met with elsewhere. A second class includes such transient types as were brought into the country by travelers, but which, because of their non-national character, failed to appeal to Lithuanian musicians and gradually fell into disuse. Among this class it is safe to include seme of the instruments which today have been entirely forgotten. However, there is also a third group instruments which are undoubtedly of foreign origin but which, because of their suitability and appeal to the people, were adopted and gradually adapted by them to their own peculiar needs, with the result that they eventually acquired a semi-naticnal character.

Fundamentally, all the instruments may be divided into the three usual groups: viz. string, wind, and percussion. These are further subdivided into eight classes which will be described separately.

The stringed instruments have been subdivided for convenience into three groups those sounded without a bow (by plucking, etc.), those bowed, and those sounded by means of a keyboard attachment.

|

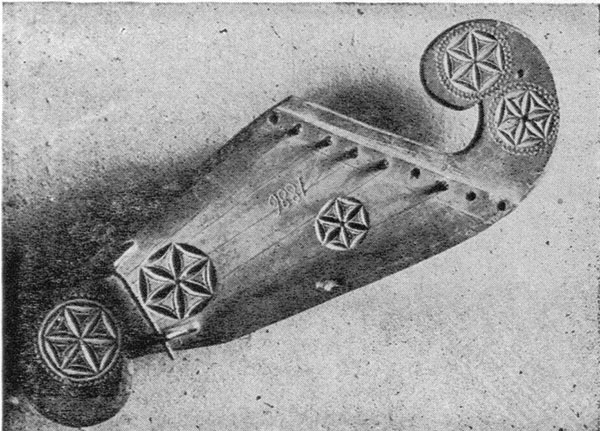

In the FIRST GROUP, the most important instrument is the Kankles. It is composed of a wooden frame with strings of various lengths stretched over it, on the principle of the piano scundingboard. Judging from recently conducted investigations, this instrument is native to the country, though it is known to the surrounding peoples also; for instance, the Letts, Estonians, Finns, Poles, and people in North-Eastern Russia. Elsewhere this particular type is unknown. Even so, the instrument disappeared so completely from Poland during the first century of the Christian Era that today not even a copy can be found. (Indeed, in describing the Polish "gęsle", historians generally use models of the Lithuanian Kankles, though these two differ somewhat in details.) Polinski, the Polish historian, states that the Kankles was a most popular instrument in Lithuania until the end of the sixteen century, after which it began to disappear. Before that time, the instrument adorned the palaces of the Grand Dukes and nobility of the country. Today, strange to say, popular fancy seems to have been caught by it again, and, with a few changes in the method of its performance, it is fast regaining its original popularity. The number of strings of this instrument varies. Examples with 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and even more strings are known, though the fundamental scale is the fentatonic. The better quality instrument is made of dogwood. Those types found among the neighboring peoples differ from the Lithuanian in a few details, especially those of the Finns and the Russians, who construct them after their own fashion. Some examples have been found where the wooden frame is sloped at the top to the right instead of to the left, as is usual. This circumstance necessitates a change in the method of performance.

The music of the Kankles is of a very melancholy character, and it was very often used for religious ceremonies. The people tell a most touching story, in the form of a ballad, concerning the origin of this instrument. It seems that a fisherman living on the shores of the Baltic had two daughters. The elder was melancholy and as silent as the night. The younger was most beautiful, and charming as the day. She fell in love with a young man who gave her a ring. The elder sister envied her this love and planned to kill her. She pushed her into the sea, declaring that in this way she would become an ornament to the bottom. The younger implored her aid as she began to sink, and even offered to give up the ring if her sister would save her. However, it was not to be, and her bones were left on the bottom to wither away. Later, her lover went fishing on the same spot, and his seine brought up what was left of her hair and her body. From these, overwhelmed with grief, he fashioned the frame and strings of the first "kankles." Finding the elder sister, he laments his misfortune and declares she will never find peace again because of her crime.

The making of some of these instruments in ancient times was combined with an elaborate ritual. "Kankles" could be made only at the time of the death of a close relative; therefore, it is no wonder that the "Kankles," made under such grave circumstances .cried and made the heart melt with its melancholy strains.

The Cymbalium is also composed of a wooden frame with stretched strings, though this frame is usually rectangular. The strings are sometimes struck by small hammers. Today this instrument is widely used in Hungary, though originally it came from the East. Some have only a dozen strings, while others with 48, 72, 80, 110, and more exist.

The Psaltery, like the Cymbalium, a forerunner of the piano, was well-known to the unlettered country folk. It had a long history among the Lithuanians, though today it is no longer used. Lepner, in his "Der Preussische Litauer" declares that it was very popular in the country before 1690.

The SECOND GROUP consists of the bowed Instruments and includes the Boselis, the Manikarka, and the Violin.

The Boselis is a primitive viol, with an air-filled bladder stuffed with peas for a bridge. This peculiar instrument is undoubtedly native to Lithuania and is most primitive of all of the instruments. A long branch is tied at both ends by a waxed string and the tone is produced by a rosined bow. The tone is strong and in quality like the double-bass. Similar types have been found among the Hottentots.

The .Manikarka is a one-stringed instrument with a bridge, similar to the cello. The name is probably a corruption of "Monochordus," a contrivance invented by Pythagoras for investigating the ratios of intervals. It is used a great deal even today by the Reformed Church in singing Chorals. Its tone is sweet and the resonance good.

The native violin is similar in shape to our modern violin, except that the frame immediately beneath the strings, instead of showing the "SS,' is covered with a skin. The tone produced is quite pretty and resembles that of the violin.

The THIRD GROUP consists of the keyboard type of instrument.

The Samogitian Cymbalium is the principle example of this type. It is widely known in that part of Lithuania known as Samogitia, and like its prototype, the Cymbalium, has a great number of strings.

The Wind instruments are divided into four classes.

The Skudutis is the simplest instrument of them all. This is a plain tube which produces a whistle-like sound when one blows across the top. Similar instruments are found almost among all people the Chinese, Greeks, Grusines, and most primitive nations are acquainted with them. There is a slight difference to be observed in their usage among the Lithuanians, however. In length the instrument is from four inches to a foot. It is generally made of wood from the young ash or the buckthorn, hollowed out. Some are hollowed out for only part of their length, others entirely, and one end is closed by a piece of wood. The open end is cut at an angle on both sides in such a manner that, after one places the pipe to the lips at this end and blows, a steady and clear tone is produced. This whistle is always used in sets of five, six, or seven, the number of performers in a concert varying with the number of instruments. The fundamental group consists of five pipes, to correspond to the pentatonic scale which they produce. Each pipe is of a different length, and all are fastened together by boards, in appearance very similar to the Syrinx or Pan's Pipes of the Greeks. The intervals of the first five pipes correspond to d-e-f-g-a; when two others are added, their tuning is a small and large semi-tone higher than a. In rare instances only three pipes are used. The music produced is simple and un-tempered, best enjoyed when heard in the open. It is then enchanting.

The Vamzdis pipe is of wood. It ordinarily has several finger holes on the sides and is blown from the end, on the principle of the Organ pipe. It was very widely used until recently, when it became gradually supplanted by more modern instruments.

It is the Clay Pipe, however, that presents the most opportunities for Lithuanian constructive genius to express itself. These pipes are shaped into animal forms and receive their names from the animals they represent. Thus we find "birds", "ducks," "horses," "dogs," and "roosters" being used as whistles by the country folk.

The Single and Double Whistle are less interesting instruments.

The SECOND GROUP of the wind instruments is that possessing the straight reed.

The Birbyne is the most representative member of this class. Though differing from the Clarinet in appearance, it produces much the same tone and can be substituted for it. Because of its limpid tone and wide range, it is very popular and extensively used. There is another of the Birbyne which is a variant made of cane. The reed is placed into the closed end of the cane. The other end is left open. Several holes are cut in the sides. The tone produced by this type is a loud one, like that of the oboe.

The Labanoru Dūda or Bagpipe was at one time very widely used, though it is almost forgotten. It is composed of four parts, each made of several pieces. The principle horn for playing the melody is similar to the Clarinet in shape, but has a curved end. There are six holes on top, one at the bottom a,nd two holes at each end on the side. The bass-horn attachment is much longer and thicker than that of the first and has no holes, since it can produce only one tone, the bass. Then there is a small tube used as a mouthpiece. These three separate horns are connected to a leather bag. The performer fills the bag with air through the mouthpiece and, holding the bag under his arm, squeezes it when necessary to produce a tone through the two horns. A distinctive peculiarity of this instrument lies in the fact that while the mouthpiece itself possesses no reed, both the other horns do.

The Ragelis was made of the natural horn, and there were several different classes of this instrument. All produce pleasing effects, whether used as solo instruments or in concert. At times they were pierced with holes in the sides. The end was fitted with either wooden or bronze lip pieces. Types similar to the Lithuanian horn can also be found among the Slavs. The tone has a mournful character, but on the whole is very charming. Today this type of horn has practically disappeared. Some horns used in hunting and for festivities possessed no reed, though these are not important. The most widely used had a small wooden reed, similar to that found in the modern Clarinet.

There are more instruments of this type of Animal Horn, but they are relatively unimportant.

The THIRD GROUP is that with the cross-reed.

The Čekštukas is a small tube with a cross-reed, producing a tone similar to a child's cry or the owl's hoot. Though today it is gradually being forgotten, in the past its use was symbolic. Soon after a wedding old friends would always produce the "child's cry" when passing the home of the newly weds, indicating their desire for progeny.

The FOURTH GROUP is the reedless type, blown with the lips, though differently than the First Group.

The Trimitas or trumpet is as well-known among the Lithuanians as are the Kankles. It is of different shapes: some tubes have very wide openings, others more slender openings, and some are straight from the lip-end to the opening. Some of these tubes are of bucthorn wood with bark while others are simply made of brass. The trumpet was used for various purposes besides entertainment: as, for example, in war, while herding, and for religious services. However, a separate species of horn, the Daudyta was most especially dedicated to religion. It was from four to six feet long and was used by the pagan priests for ritualistic purposes. The ordinary Trimitas is occasionally made as lonp; as fifteen feet.

This instrument as well as others which are thoroughly Lithuanian, is widely known to the people through the fables and folk songs which have grown up around it. The name itself, according to the historian Daukantas, is made up of two purely Lithuanian words tris, meaning three, and mytas, meaning stake. It seems that the first Trimitas was made of a pole or stake which had been cut into three parts, hollowed out, and put together again with tar. The name, therefore, means a three-pieced pole; i.e., a pole split into three pieces. The instrument itself was so popular and widely used by the ancient Lithuanians that seme historians of the Middle Ages attempted to analyze the name of the nation itself with its help. A story is told of the Grand Duke Kernius, son of the fabled Palemon, who came from Rome to the river Vilia, and found the Lithuanians living on its farther side. These people, being savages, had no name to the Romans, and Kernius was hard put to it, When referring to. them for some appel-lation^When he noticed that they used the trumpet so much in their daily lives, he began thinking of that country in Latin as the "land of the trumpet." Litus, meaning counry or land and tuba being the Latin for trumpet; the two words put together formed lituba, which gradually became Lietuva or Lituva, as the Lithuanians today designate their country.) This story most probably is only a story, but is interesting in that it demonstrates the great age of the Trimitas. The earliest records to be found are those given us by Arnold Schering, who states that "bronze trumpets have been used in Scandinavia and by the Baltic peoples as early as the twelfth century before Christ." Karamzine, a White Russian historian, declares that the Lithuanians used trumpet of wood in the twelfth century A. D.

In some districts of Lithuania ensembles of five, seven, and more trumpets are used with very pleasing effects. Curved wooden trumpets covered with birch-bark are also well-known, and quartet groups are often found, sometimes even in churches. Part of the pagan Lithuanian ritual still extant explains the duties mounted trumpeteers leading the funeral procession to the graveyard.

Small orchestras composed of the Ragelis, trumpet, the native Violin and Drums were formed by the country folk, and, it is reputed, with excellent results. These small horns (i.e., the Ragelis) were often most artistically ornamented, and at times Lithuanian hieroglyphics were carved into the sides. The Ragelis possessed a peculiar notation, differing from any other musical script then known.

Percussive Instruments form the Third and last section. tuba being the Latin for trumpet; the two words put together formed lituba, which gradually became Lietuva or Lituva, as the Lithuanians today designate their country.) This story most probably is only a story, but is interesting in that it demonstrates the great age of the Trimitas. The earliest records to be found are those given us by Arnold Schering, who states that "bronze trumpets have been used in Scandinavia and by the Baltic peoples as early as the twelfth century before Christ." Karamzine, a White Russian historian, declares that the Lithuanians used trumpet of wood in the twelfth century A. D.

In some districts of Lithuania ensembles of five, seven, and more trumpets are used with very pleasing effects. Curved wooden trumpets covered with birch-bark are also well-known, and quartet groups are often found, sometimes even in churches. Part of the pagan Lithuanian ritual still extant explains the duties mounted trumpeteers leading the funeral procession to the graveyard.

Small orchestras composed of the Ragelis, trumpet, the native Violin and Drums were formed by the country folk, and, it is reputed, with excellent results. These small horns (i.e., the Ragelis) were often most artistically ornamented, and at times Lithuanian hieroglyphics were carved into the sides. The Ragelis possessed a peculiar notation, differing from any other musical script then known.

Percussive Instruments form the Third and last section.

In order of time, these instruments were among the Lithuanians as elsewhere, the most primitive. Rhythm in music being the foundation of all else, means of producing it were of necessity first contrived. Knocking, rattling, striking, clapping, and, clucking, were the natural means of producing rhythm, and to aid the people in expressing that feeling, large and small drums, rattles, knockers, glass and iron tappers, and boards of different lengths were utilized everywhere. Some of these primitive instruments are to be met with even today.

Among the Lithuanians, it was customary to vary the ensembles for different occasions. For weddings bagpipe, horns, Kankles, and occasionally some other instruments were used. However, on the eve of the nuptials, when a farewell party was generally given, only the Kankles were played. Special music was performed on the pipes as the bride's dowry was brought out. In fact, the Lithuanian peasant is an inveterate musician. Every important event in his life must be celebrated with music that has become traditional through the ages. There is one combination in particular, in which the Skudutis, Kankles, and singing alternate; in the writer's opinion, this "trio" composition is the oldest in Europe today. When the music foi this is played on well-tempered instruments, (he result is a terrible dissonance. However, when performed upon the untempered instruments for which it was composed, the effect produced is truly beautiful.

|

| V. Marčiulionis - Kanklės' Player |