Managing Editor P. V. Vygantas

|

www.lituanus.org |

|

Copyright

© 1957 Lithuanian

Students Association, Inc.

June,

1957 No.2(11)

Managing Editor P. V. Vygantas |

|

THE DEVELOPMENT OF MONUMENTAL ART IN ANCIENT LITHUANIA

DR. POVILAS RĖKLAITIS

DR. POVILAS RĖKLAITIS, born in 1922 in Kaunas, Lithuania, studied philosophy, history of art and library science in the universities of Kaunas, Vilnius, Poznan and Tuebingen. At present he is living in Germany and has written many articles on history of art.

All the centuries of Lithuania's history have teen accompanied by works

of architecture sometimes connected with sculpture and painting of

decorative or symbolic character.

|

| VILNIUS. Ruins of Upper Castle's living palace. Present view. |

However, our knowledge of the

earliest centuries from the 12th to the 14th Is very icant, and the

surviving monuments are not numerous. In the period of transition to

early historic times the widely distributed Lithuanian fortresses were

a very important phenomenon of our country's material culture. Their

social, architectural and urtanistic character determined the

beginnings and later development of monumental art in Li'huania. The

Lithuanian word "pilis," meaning an ancient fortress or castle, is

similar to the Greek "polls." Indeed, "pilis" meant not only the

residence of the feudal "kunigas" (king) in the formative period of the

Lithuanian empire but also an embryonic town, an administrative and

economic canter made up of the fortified high ground and "suburban"

settlements, as we know from analogies in other countries of Eastern

and Central Europe.1

The defensive walls were adapted to the border of the plateau and took

the form of an irregular ring, inside which were a great number of

buildings the ruler's palace; dwellings for his attendants,

relatives, servants, warriors and artisans; and sanctuaries. In the

earliest times these buildings were constructed exclusively of wood, as

was natural in a country rich in forests but lacking stone suitable for

masonry constructions. We can only guess at their teauty and fanciful

forms by studying the rural wooden buildings of later times i. e.,

rural churches, bell towers, granaries ("klėtis") and so forth the

oldest known examples of which date tack to the 18th century. (The

exploration of this subject belongs to ethnography.) All wooden

structures of earlier periods have been destroyed by fire, and only

conical hills, now overgrown with grass and bushes, mark where the

fortresses formerly stood. The excavated traces of wooden structures on

these sites make up a separate problem of archeology. The attention of

the art historian is drawn to the few stone monuments that have been

preserved from the earliest historic times, or have teen found during

excavations, and that permit us to retrace the aspect of early

monumental art.

1. THE FORTRESS AND TOWN

OF VILNIUS

|

|

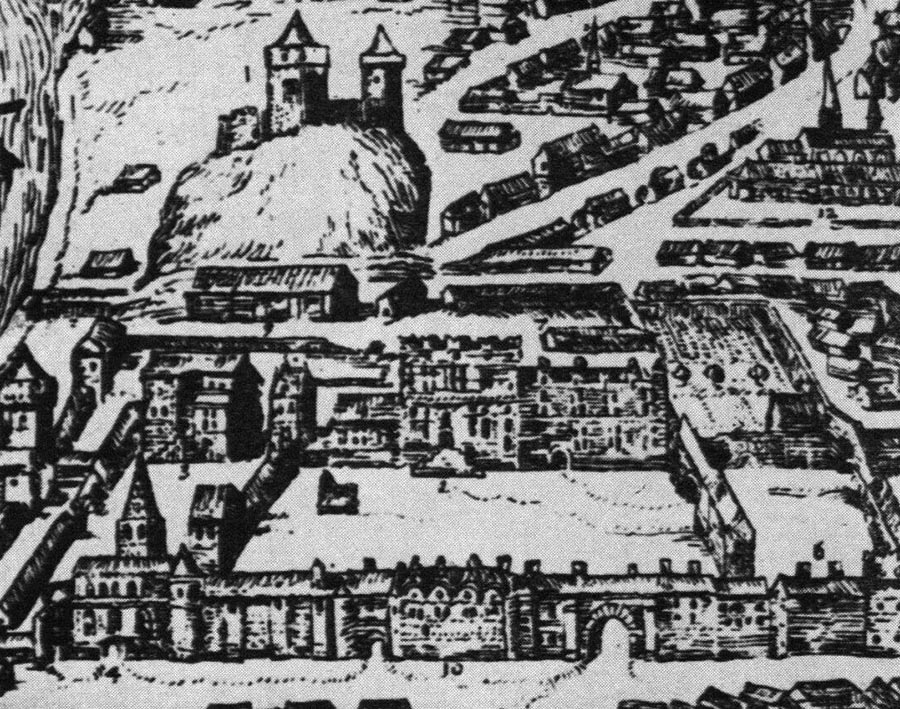

VILNIUS.Feudal Region in XIVcentury,

Fortress, Ducal Palace, Cathedral.

(Frim vilna Litvaniae Metropolis, G. Braun 1581) |

VILNIUS. Feudal region on the left,

Municipal Regionfree city with city hall on the right. Column in the

middle is symbol of strength.

From a drawing by T. Makov-ski in 1604. |

The construction and subsequent growth of the stone fortress at Vilnius, the seat of the sovereigns of the Lithuanian empire, had prime importance for the further evolution of Lithuanian culture. In 1940 excavators of the fortress the so-called Upper Castle, or Gediminas Hill discovered the oldest cultural layer, which dates back to 400 A. D. and already belongs to the Baltic-Lithuanian tribes.2 The oldest stone structure of the fortress dates from the 14th century, the time of the heirs of the Grand Duke Gediminas; it combines granite boulders with brick and lime, which is typical of Lithuanian military architecture of the 14th and 15th centuries. Around 1420 the Grand Duke Vytautas erected, of the same materias, new defensive walls, with three towers, and a palace building; their magnificent ruins still dominate the panorama of the town.3 As early as i he 14th century there existed immediately at the foot of the fortress-hill, at the confluence of Vilnele Brook and the Neris River, an urban complex later called "Lower Castle." Its stone walls, irregular and with an unsymmetrical ground plan, were joined with the fortress on the hill and enclosed a large area with a great number of buildings of various types, among which was the palace of the Grand Duke.4 This palace was originally Gothic; in the 16th century the Lithuanian Grand Dukes Sigismund the Old and Sigismund August Jogai-lians built a new, Renaissance palace, with attics on its facades hiding the roofs around a cortile, or Italian-style courtyard with galleries; the cooperation of Italian architects must be presumed. This palace is shown in "Vilna Litvaniae Metropolis," the panorama of the town engraved by Braun and Hogenberg in 1581 and the oldest view of Vilnius; the palace, together with the surrounding buildings, was torn down in 1799-1803.5 As early as the 14th century this "fortress-town" of Vilnius became the country's political and religious center. A market place outside the walls plus neighboring settlements at the same time served as a crystallization point for a free merchant town. In 1387 the new suburb of Vilnius was granted city rights,6 although the German colonists of Vilnius had long enjoyed the civil rights of Riga. In the 16th century the town was girded by a wall, and fortified gates were built.7 Thus the town's social differentiation is clearly visible in its topography and monumental architecture: the formerly open municipal area around the market and the town hall, and a separate feudal area, earlier walled in as a "castrum," with its palace, temples and ancient stronghold on the hill having the same significance for Vilnius as the Acropolis has for Athens or the Kremlin for Moscow.

2. THE FORTRESSES ON THE HEIGHTS

We find stone "pilis" similar to the one at Vilnius in several other places in Lithuania. Extensive ruins have been preserved at Gardinas, on the Trakai Peninsula and at Naugardukas; in Veliuona and Merkine the stone structures have disappeared. In these places we observe the remains of an old fortress on a height, ringed by a wall; outside, and separated by a moat, is a suburb with i's own d:fense arrangements. Only the Gardinas ' pilis" has been satisfactorily explored, in 1931 to 1949. At a depth of eight meters the excavators found the remains of two 12th-century towers, measuring 10 by 10 meters and made of Byzantine bricks 4 by 17 by 28 cm. This is the oldest secular brick structure in the country, dating from the time Gardinas was under the rule of Ukrainians from Kiev.8 Above the 12th-century stratum, at depths of 6, 5 3, 4 m. are layers dating from tha Lithuanian culture of the 13th and 14th centuries and the remains of a large Gothic castle erected by Vytautas in 1398. This castle has an irregular ring wall and is built of bricks 8 by 12 by 27 cm and boulders. A Gothic monument that may be even older is the brick tower at Lietuvos Akmene (Kamenec Litovsk), the remains of a former castle which may have been built in the 13th century. The ring-shaped walls and their imposing dimensions and the severity and massivenes of the structure are characteristic of the oldest Lithuanian military architecture. In this period the elements of prehistoric culture are still predominant, but the influence of the neighboring Kiev empire and the Gothic world to the west begins to increase.

|

|

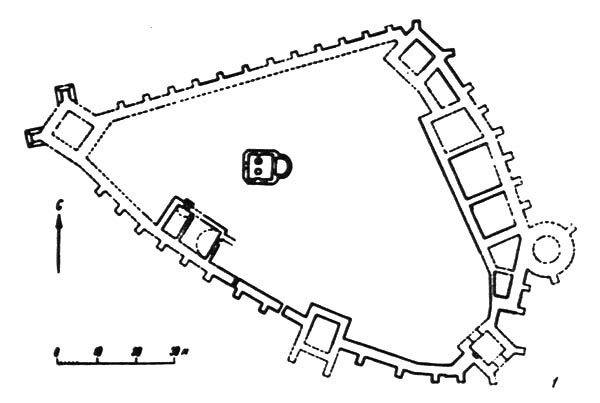

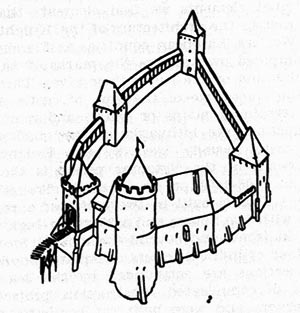

| GARDINAS. Plant and reconstruction of the castle of Vytautas the Great (1398). The Vytautas' church, the foundations of which have been excavated, is situated inside the castle yard. | |

|

|

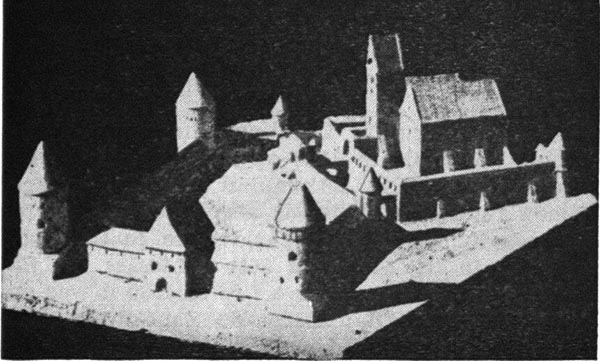

| TRAKAI. Plan of the island castle of Galve lake. Forecastle and Ducal Palace with representation hall. Gothic vaults of the hall have been rebuilt. Drawing by S. Lukoševičius. | TRAKAI. Model of the island castle in the Galvė lake, XV century. Forecastle and Ducal Palace. |

3. THE OLDEST CHURCHES

Christian sacred buildings in Lithuania, as well as in the empire of Kiev, were always built close to the rulers' residences, and the earliest churches wtrj fortress-churches. In 1933 a small (eight by nine meters) four-cornered church with a rounded apss and two interior pillars was excavated within the walls of Vytautas' castle in Gardinas. This church, dated at the end of the 14th century, clearly shows the idea of a central-type building smp ified into an elementary cubic structure of Rrmanesque taste, the bricks that are used being rot Byzantine in shape but slender Gothics ones (8 t y 16 by 31 cm)9 Below this fortress church of Vytautas the foundations of an earlier church, purs Byzantine in style and dating from the 12th century, were excavated. This church has three rounded apses, and it possessed a dome; fragments of faience tile were found in the floor and walls. Other fortress-churches existed in Naugardukas, Trakai and Vilnius, which had several of them. In 1956 the St. Anna Church, mentioned as early as 1390 and 1398 it had presumably been built earlier as an "intra muros castri (within the castle walls) was excavated in the former fortress-town area of Vilnius; it too, had a rounded apse.10 According to tradition, the Cathedral of Vilnius was built in 1386 on the site of a pagan temple, when the Lithuanian dukes embraced Roman Catholicism; it was also a fortress-church (ecclesia in castro), and stood close to the ducal palace.11 In the 15th and 16th centuries the Cathedral was Gothic; after a fire in 1530 it was enlarged by the Italian Bernardo Zenobl and Giovanni da Fiesule, and their version can be seen in an engraving made by T. Makovski in 1604. The present classical design is the work of the Lithuanian architect L. Stuoka-Gucevičius, who in the years 1777 to 1801 put up a structure of imposing gravity in the form of an ancient Greek temple, with a six-columned portico, that is in perfect harmony with the remains of the medieval stronghold and remains a true symbol of the former Lithuanian empire.

A second impulse for the development of ecclesiastical architecture was furnished by the monastic organizations; preserving a greater measure cf independence than the sovereign, they settled outside the fortress walls (extra muros castri) and therefore supplied their own defense arrangements. In Koloža, outside the fortress of Gardinas and close to the Nemunas River, are the remains of a 12th-century church in Byzantine style; two apses and some sections of wall, decorated with faience tiles in gecmetiical patterns, have been preserved of this basilica, which formerly had a dome; inside the church hundreds of acoustical vases are walled, in the manner of classical antiquity (Grecian "echea"). This church had embrasures above the interior galleries for defense. New explorations have confirmed that this church, built for the special cult of Saints Boris and Gleb, was connected with a monastery.12 In the 14th century the Franciscans and later the Dominicans founded their first cloisters in Vilnius, outside the fortress walls; missionaries of these orders had visited Lithuania as early as the 13th century.13

4. THE WATER AND PLAINS CASTLES

Gothic forms came to Lithuania from Western Europe largely in the second half of the reign of Vytautas. Under this statesman's farsighted policy, the Lithuanian Grand Duchy was united in a free alliance with the Roman Catholic kingdom of Poland, upon whose throne Jogaila, a cousin of Vytautas', was seated in 1386. The Western character of Lithuanian culture was now definitively determined. Vytautas' struggle against the Order of German Knights and in alliance with it against Jogaila undoubtedly gave new impulses to military architecture in the 15th century. In times of armistice Vytautas exchanged architects and artisans with the order; Lithuania's 15th-century castles were marked by new features and developed original features in their total design. Beside local, traditional elements we find elements that have their root in the architecture of the Knights or in such Western European countries as Flanders, and superimposed over all are the marks of the creative planning of the rulers themselves. This period saw the emergence of the type of castle adapted to a terrain of plains or water, and marked the introduction into Lithuania of the quadrilateral-pian castle usually used by the Knights. The maste rwork of the Vytautas period is the castle built in 1406-1409 on an island in Trakai's Lake Galvė.14 This is built in two sections: a residence castle with two houses and a 25-meter-high watch-tower in front, and beyend the moat a fore-castle with four cylindrical towers on square foundations; both sections are surrounded by the sea. These towers, of complicated construction, project from the corners and were built for bombarding from the flank; they are a peculiarity of construction not typical in the Knights' architecture.15 At Trakai defense arrangements of Western European origin were adapted to local requirements and ideas of beauty. This castle occupies a space of 8160 square meters and is built of at least 30,000 cubic meters of boulders; only the exterior facing and the vaults were constructed of brick. In the years 1929 to 1943 the Lithuanian Office for the Preservation of Cultural Monuments carried out thorough excavations and preservation work on this castle, which has been in ruins since the 17th century.16 To the period of Vytautas also belong the castle at Kaunas, quadrilateral with cylindrical corner towers, and the fore-castle on the Trakai Peninsula, both of which are now in ruins. The chronology of the castles at Medininkai, Kriavas and Lyda has not been firmly established; it is probable that they all belong to the 15th century, too.17 The trapezoidal ground plan of these castles shows a synthesis of Western and Eastern forms. The basic elements of the Vytautas castles determined the further development of all military architecture in Lithuania for the next two centuries. In the 16th century water castles with puadri'ateral ground plans were built, for instance at Geranainys and Myrius; around 1600 a castle was built at Vytenai, and many other smaller plains castles and palaces were constructed, all fortified and having the cylindrical or octagonal towers so characteristic of the feudal period in Lithuania up to the 17th century. Many factors point to the supposition that Muscovite quadrilateral castles of the 16th and 17th centuries (the earliest example is Ivangorod, built in 1492) were influenced by the Vytautas-type Lithuanian castle. The cultural influence of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania can be seen in other aspects of Moscow's life jurisprudence, for instance; the Muscovites imitated the Lithuanian Statutes.

5. GOTHIC IN THE TOWNS

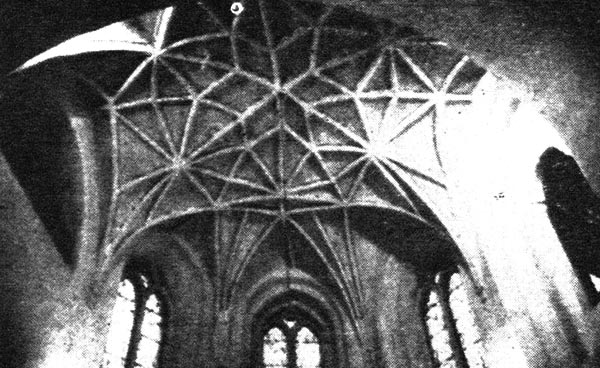

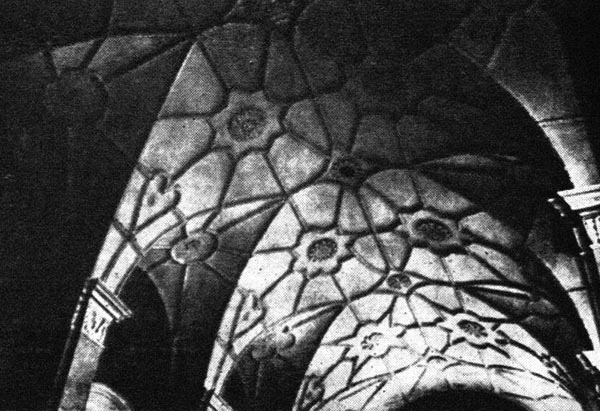

There are a number of brick structures in Lithuania's towns dating from the 15th and 16th centuries. The war between Lithuania and the Knights, which lasted more than 200 years, was ended by Vytautas, who then initiated commercial relations with Prussia; this was of great benefit to Lithuania's cities. After the victory of 1410 the cities began to bloom, and their economic importance far transcended that of the old economic centers of the fortresses' suburban setllements. Trade with such cities as Danzig and the establishment of German merchant colonies also enhanced the growth of Gothic culture in Lithuanian towns. Vytautas preserved and extended the autonomous status of towns in the form of Magdebur-gian town rights, which were granted to Kaunas in 1408.18 This development continued through the reigns of Kazimieras Jogailaitis (1440-1492) and Aleksandras (1492-1506), and urban planning, architecture and construction techniques all partook of an obviously Western character in this period. The slender Gothic bricks became common in the towns, as well as Gothic vaults and the system of buttresses. Several Gothic churches of the 15th century still survive as large parish churches in the cities St. John's, in Vilnius; Sts. Peter and Paul (now the Cathedral), in Kaunas; St. Mary's, in Gardinas; and smaller churches in Merkinė, Veliuona, Kėdainiai and Trakai. The brick Gothic so-called Baltic or Northern Gothic style to which all these monuments in Lithuania belong differs markedly from the sandstone Gothic of Western Europe. The characteristic vertical rhythms of Gothic wall structure and the decorative carving were impossible in the North, where the lack of sandstone necessitated the use of brick. The Baltic Gothic works with planes and underrated walls of red bricks, revealing the monumental logic of cubic masses. This crude severity is softened by plain blind windows, and friezes and embrasures of shaped brick. The monotony of the bare red-brick walls is enlivened by whitewashed niches and the insertion of glazed or black-burned tricks. The hall-church nave and aisles of equal height is most characteristic. Lithuania's brick Gothic vaults are highly decorative; they include 15th-century star vaults, in which the ogives that transmit the vaulting's weight to the pillars are arranged in large stars; net vaults, dating from the late 15th and the 16th centuries, and very characteristic of late Gothic, in which a web of ogives with no constructive function covers the vaults; and, finally, the honeycomb vaults, decorated with various crystal-shaped cavities; the finest surviving examples are in the sacristy of the Bernhardin Cloister in Vilnius.

|

| KAUNAS. Gothic churches. XV century |

|

| KAUNAS. Church of St. Nicholas. Choir vaults. Late Gothic. XV-XVI century. (Photo by architect Georg Gettner.) |

|  |

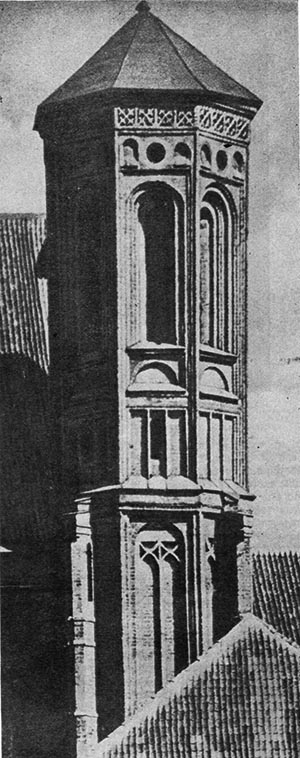

VILNIUS. Cloister Church of the Order of Bernhardine Southeastern Tower. Built about 1525. | VILNIUS. Facade of the church of St. Ann. Second half of XVI century. |

6. THE LATEST, 16th-CENTURY GOTHIC

The Order of Bernhardins i. e., strict-observance Franciscans (in Poland and Lithuania) -established cloisters in Vilnius and Kaunas in 1469 Construction of these cloisters' churches continued into the 16th century, and although the Renaissance began to spread in Lithuania, the Bernhar-cins clung stubbornly to the medieval Gothic tradition of art, which survived in Lithuania until the end of the 16th century. This late Gothic was very original and inclined to variations. For instance, the bell tower of the Bernhardins' church, built about 1525 an octagonal structure decorated with frames of bricks in profile and rounded arch openings is a solution that does not violate the true style of brickwork. The increased decorativeness of the facades, broken up by many blind windows, can be seen in other 16th-century brick Gothic churches for instance, those in Zapyškis and Koden and in the castle at Myrius. This trend toward a fanciful decorativaness went far to give the ornamental details of the walls a more variegated character and a sculptured look. The most famous example of this style is the Church of St. Anna, near the Bernhardins' cloister in Vilnius, founded at the end of the 15th century as an oratory for the St. Anna Fraternity; the remarkable facade erected in 1576-1581 by an unknown Flemish architect, is a masterful execution in trick of various motifs of late French-Flemish sandstone Gothic combined with motifs of local provenance into a complicated decorative whole.19 The 16th- century Gothic gable of the so-called Perkūnas House in Kaunas a marvelous relic of the old civil architecture of this ancient trade center on the Nemunas River, where Hanseatic merchants gathered had a similar genesis

|  |

VILNIUS. Church of St. Michael. Buttresses ending in ca-pitals. 1594-1625. | VILNIUS. Church of St. Michael. Renaissance vaults decorated with stucco ribs. 1594-1625. |

7. THE PROBLEMATICAL TRANSITIONAL AGE AND THE RENAISSANCE

The period of the Renaissance in Lithuania is marked by reminiscences of medieval archaism. This is evident in the above-mentioned restoration ot the Cathedral in Vilnius after 1534 and in so far as we can judge from old engravings in the former Eucal Palace, put up in the Renaissance period. The similar attics of some remaining buildings in the town seem fairly remote from true classical Renaissance art, and the motifs of the friezes of rounded arches used in them are of a cuasi-Romanesque character. (The Romanesque frieze of rounded arches came into the neighboring Ukraine and Novgorod from the West in the 12th century and survived there for a long time.). We can speak of the revival of archaism in Lithuania as the first step toward something new.

The archaism also manifested itself in the return to Byzantine forms of the Orthodox churches constructed in 16th century. After the prohibition of the use of brick in constructing Orthodox churches was repealed, in 1514,20 a series of brick churches rose in the first half of the 16th century; they were now, paradoxically, dependent on Western forms: A Byzantine ground plan is united with Gothic vaults and decoration that employs revived "Romanesque" motifs. All these churches were fortified, with towers on all four corners and galleries with loopholes, and their hybrid design places them among the most curious products in the history of art. The oldest examples of this Gothic Byzantine syncretism are St. Trinity, in the Basilian Cloister; St. Nicholas, on the great market; and St. Mary's Cathedral all in Vilnius; surviving to our day are the fortified churches near Skribonlai (Lyda District); Sinkevičiai, near Slanimas; and the cloister church in Suprasi, near Baltstogė.21 Žemaitija (Samogithia, or Low Lithuania) has an interesting parish church at Šiauliai, built half a century later and decorated with Romanesque simple vertical mouldings and friezes, though the building itself is a fortified construction akin to Gothic. Cylindrical flanking towers are preserved in some other churches of the old brick co-s'ruction (Simnas, Kamojai, etc.). The church at Smurgainys exhibits a rare octagonal plan, and has attics of Romanesque shape. Many relics of this problematical transition period in the country have not yet been fully explored. Around 1600 church architecture began to mix Renaissance and early baroque forms with the traditional Gothic e'ements. This can be seen in the Bernhardin nuns' churches of St. Trinity, in Kaunas, and St. Michael, in Vilnius. The latter, a small church of one nave, has buttresses ending in "classical" capi-ta's and cornices; the barrel vault is decorated whh stucco ribs having rosette motifs; and the facade, again, is flanked by a pair of traditional cylindrical towers, of slender proportions. Even the uniouo late-Renaissance-style Calvinist church in Kėdainiai (1624-1654) has cylindrical towers at all four corners, like the fortified churches of the old type.

8. PAINTING AND SCULPTURE

Examples of monumental painting and sculpture of the 15th an dl6th centuries in Lithuania are scarce, owing to considerable losses during the first Muscovite invasion of 1655-1661, which do-vastated Vilnius and other towns. On the walls of the ruined island palace at Trakai we can see fragments of a cycle cf 15th-century frescoes representing scenes of homage to a secular ruler and portraits of saints; the style of the frescoes is related to the Balkan school of painting. Vestiges of pol-chrome wall paintings remain in the churches at Iškeldė and Rykantai (16th century). Many examples of 16th-century panel painting have unfortunately not yet been critically described. Two of them merit considerat'on for their cultic significance and the typical qualities of the local school that they reveal: the icon of St. Casimir, patron saint of the Duchy, in the Vilnius Cathedrai (the saint's tomb-chapel), and the Holy Virgin in the chapel of Aušros Vartai (Dawn Gate) a painting of high artistic value (between 1550 and 1650 ) 22 Written sources mention Gothic sculptures in the Vilnius Cathedral that no longer exist. Fragments of decorative Renaissance carving have been found in Vilnius. Several marble tombs survived the Muscovite devastations; the oldest, a marble tomb plate of Chancellor Albert Goštautas dated about 1539, is attributed to Giovanni Cini, and its severe frontal composition is medieval in feeling.

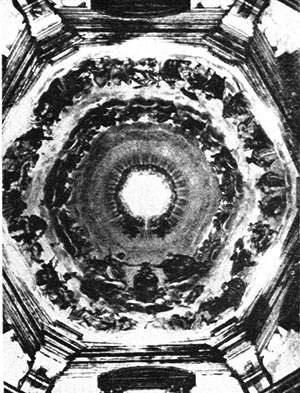

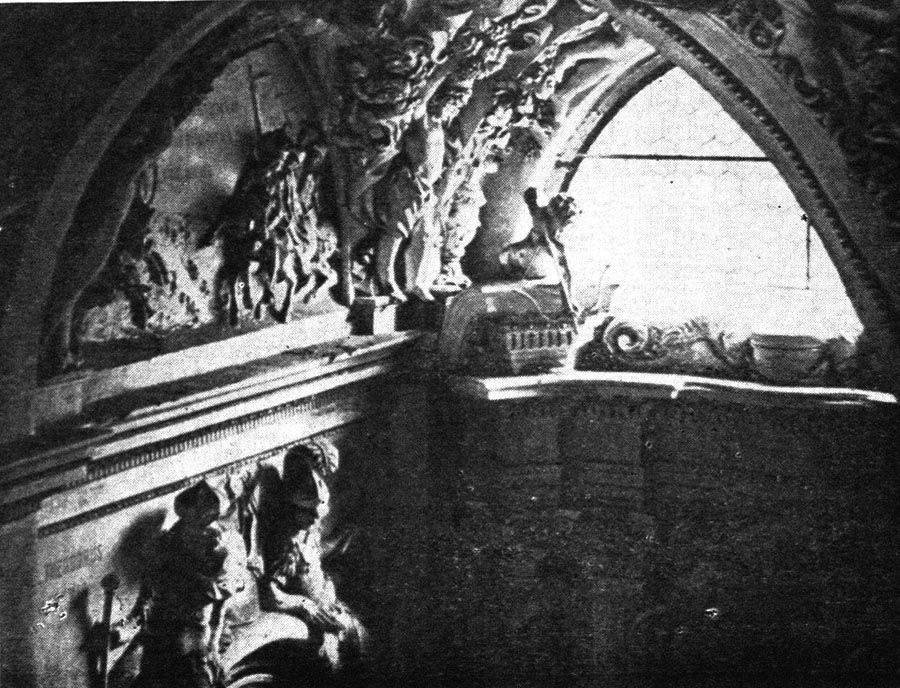

9. ITALIAN BAROQUE IN LITHUANIA

The reform of the Roman Catholic Church initiated by the Council of Trent and propagated by the Order of Jesuits reached Lithuania at the end of the 16th century, and during the 17th century It turned monumental art in a new direction. The religious fervor of the Lithuanian aristocracy and their inclination toward splendor stimulated the promotion of great monumental tasks. The noble families of the Radvilas, Pacas and others, who exercised autocratic power during the union between Poland and the Grand Duchy, built luxurious palaces and modern fortresses, as at Biržai and Nesvyžius, and they contributed generously to ths construction of cloisters and cloister churches. It was a period of flowering for the Jesuits, Carmelites and Dominicans. The Jesuits' center was the Academy of Vilnius, established in 1578, which in the 17th and 18th centuries grew Into a large complex with five arcaded courts.23 Only now was the Christianization of the people accomplished and Calvinism among the upper classes victoriously rooted out. The new art developed in Italy and brought immediately by the noble patrons to Lithuania, where it interupted the local evolution was an expression of the triumph of the Roman Catholic Church. During this period many Italian architecs, painters and sculptors worked in Lithuania. The Duchy's first baroque edifice was the Jesuit church at Nesvyžius, built in 1586-1588 by the Jesuit architect Bernar-doni de Como. The plans of the Jesuit churches were usually sent to Rome for approval. The first baroque church in Vilnius, the Jesuits' St. Casimir, was built in 1604-1615 after the scheme of the Church of II Gesu in Rome, a basilica with a dome at the crossing. At the same period were built the tomb-chapel of St. Casimir, as an annex of the Vilnius Cathedral (1624-1636) and the Carmelites' St. Theresa's Church in Vilnius (1638-1652), both of which followed Roman prototypes and were richly decorated with stucco, frescoes and marble. Two magnificent baroque monuments were erected in Lithuania after the liberation from the Muscovite occupation at the end of the 17th century: The large cloister of Camenduls, founded by the Li:huanian Chancellor Christoph Sigismund Pacas and built in 1667-1674 by Italian architects in the forest of Pažaislis, near Kaunas, is marked by a grand unity of plan. The cloister's church is a synthesis of the ideas of Borromini and Venetian classic architecture. The hexagonal dome, 14.8 meters in diameter, is a rare solution for Europe. This church's frescoes are the richest in Lithuania; they were painted by Italian masters Michelangelo Palloni, Delbene, Fernando della Croce who had affinities with the Venetian and Exilian Baroque schools of painting.24 Another important cloister, for the Augustinian Order, was founded at Antakalnis, near Vilnius, by Michael Casimir Pacas, the commander of the Lithuanian army. The great domed church was built by Jan Zaor and Fernando da Lucca, and is famous for its array of stucco figures and reliefs carried out by the Milanese Pietro Peretti and Giovanni Galli, with the help of local masters. The style of this sculpture is relatively calm and almost classical, and it is astonishing for its naturalistic details.

|  |

| VILNIUS. Church of St. Theresa. First half of XVII century | PAŽAISLIS near Kaunas. Frcscoes of the Dome. End of XVII century. |

|  |

| ANTAKALNIS near Vilnius. Church of Sts. Peter and Paul. Stucco scilpture of St. Florian. End of XVII century. | ANTAKALNIS near Vilnius. Church of Sts. Peter and Paul. Chapel of Holy Warriors. End of XVII century. |

10. LITHUANIAN LATE BAROQUE

In no other period were as many churches erected in Lithuania as in the 18th century, and the light baroque church became a familiar part of the Lithuanian landscape. A very characteristic feature of these churches is a pair of extremely slender towers, resembling minarets; they can be seen in all the counties of the Grand Duchy including Polock, Mohilev and Gardinas, as well as in Žemaitija and Latgali j a. The verticalism of the Northern Gothic appears here in the disguise of the Southern baroque. This type of tower marks a union of the angular flanking towers of local tradition with the ideas of Borromini.25 Most of these churches are of the basilica type, with interior rows of columns. Of about a hundred examples, two are especially distinguished: the Missionary Ascension Church and the Benedictine nuns' Church of St. Catherine, both in Vilnius. The Jesuits' church in Kaunas and the slender tower of the Kaunas Town Hall, completed in 1775, also belong to this group. Archival investigations have shown that the Lithuanian school of late baroque architecture had its origins in the cloisters, and that many of the architects were monks who were zealous students of Italian architecture. Ecclesiastical architecture ("Kalithectonic") was taught at the Jesuit Academy and also in the Dominican cloister-schools. One difference between the Jesuit and the Dominican baroque must be noted: The Jesuits' buildings are heavier and more severe, being more closely related to Roman examples (e. g., the facade, altars and campanile of St. John's Church), whereas the late baroque of the Lithuanian Dominicans was oriented to Piemontese prototypes and has more fancifulness and grace which are also manifest in the very original compositions of the interiors, such as the Dominicans' St. Spirit Church in Vilnius, devised by the Dominican Father L. Grincevičius (Hrynce-wic?). The Basilian Order was also active; the architect A. Ausikevičius (Owsikiewicz) prepared the designs for a large project for the Basilian Cloister in Barunai and the reconstruction of the church of Trinity Cloister in Vilnius. Besides the local masters, an active part was taken by the Flemish artists T. Dydresteen and J. Pens, the Dalmatian Father Teychert and the Italians A. Paracca, A. Casparini and F. Placidi. Some late baroque churches in Lithuania have central domes e. g., the Sacred Heart Church of the Visitation Order, in Vilnius, and the Dominicans' church at Liškiava. The interior of St. Cross's Church in Kaunas has 18th-century fresco paintings, and the vaults of the r ominican church at Kalvarija, near Vilnius, have frescoes in the manner of A. Pozzo which create an illusion of reaching up to infinite heights.. A splendid baroque fresco, "The Holy Virgin Shelters the Jesuits," was discovered on the ceiling of the former refectory of the Jesuit Academy in 1928. Baroque art became indigenous, and its influence can be seen in folk-art ornaments and in rural wooden architecture.

|

| VILNIUS. Missionary cloister church. (1753). |

|

| VILNIUS. Cathedral rebuilt by architect Stuoka-Gucevičius (1777-1801). On the left is the bell tower, built on former defensive tower (XV century). On the right is St. Casimir's chapel built by architect C. Tencella (finished in 1636) and the tower of the Upper Castle (XV century). |

11. CLASSICISM AND ROMANTICISM

The aspirations toward a revival of classical antiquity that arose at the end of the 18th century were felt in Lithuania's cloister-schools too. The first exponents of this new direction were the Franciscan Fathers K. Kamienskis and K. Karega and also the Italian Carlo Spampani, an architect for residences of nobility. The change to the new v/as a'so made by the Jesuit Academy after it was transformed by the abolition of the Jesuit Order in 1773 into the "Supreme School of Lithuania"; later it became the University, and M. Knakfusas, a professor there, designed the new facade for its astronomical observatory (1782-1788) and White Hall and began the Bishop's Palace at Verkiai. The founder of Lithuanian classicism was L. Stuoka-Gucevičius (1753-1798), who rebuilt the Vilnius Cathedral, designed the Vilnius Town Hall and completed the palace in Verkiai. The church at Jonava, the palaces at Čiobiškis and Derečinas and ether of his creations are free of arid, academic classicism and manifest a great talent for the organization of architectural ensembles and for the we'l-weighed and clear disposition of decorative elements. Other masters of classicism were M. Šulcas, K. Podčašinskis and the Dominican Father L. Eortkevičius, wl~o built a circular church at Su-derva in 1802-1811. Classical sculpture is represented by the Italian Rhigi, Andrea Le Brun (d. 1831) and K. Jelskis (d. 1871). A school cf painting at the University of Vilnius, established in 1798, was active until it was closed by the Russians in 1831, and it contributed considerably to raising Lithuania's artistic culture in the first half of the 19th century. P. Smuglevičius (1745-1805), who founded the school, painted many large religious pictures and frescoes for the churches of Vilnius. His most outstanding followers were J. Oleškevičius (1777-1830) and J. Rustemas (d. 1835). The school's finest achievements were in the field of portrait painting.^ The following years, under the 19th century Rufsian oppression, were unfavorable for the evo-lu'ion of monumental art. The persecution of the Roman Catholic Church interrupted churchbuild-ing. Only some of the rich landowners kept their social position and were able to build mansions or. their estates; they favored such classical patterns as the usual porch on columns, or, under the influence of romanticism, attempted to create replicas of medieval castles in neo-Gothic stvle (th<-manors at Vaitkuškis, Raudondvaris, Faudone, Lentvaris, etc.). During th? 19th centur" the cities of Lithuania lived through the same rriris of elec-ticism as the cities of Western Eurore. As a congruence of the unfavorable conditions, the talented painters, with few exceptions, emigrated to St,. Petersburg or Warsaw. The idea of national and social evolution was slowly growirg among the people of Lithuania, and in our century it called far a new monumental expression.

The

history of monumental art in Lithuania exhibits appropriations from

various sources and f he'r assimilation into original creation. The

unity of the artistic culture and the independent attitude toward

foreign prototypes in the territory organized by the Lithuanian Grand

Dukes and their fol'owers is evident in all periods, and new research

into the history of Eastern European art tends more and more to

recognize in Lithuania a region of active stylistic creativit"' between

the two worlds of rrt the Byzantine, in the East, and the

Gothic-baroque, in the West.

1

Herbert Ludat, Vcrstufen und Entstehung des Staedtewesens in Osteuropa

(Zur Frage der vorkolo-nialen Wirtschaftszentren im slawisch-baltischen

Raum), Koeln-Braunsfeld 1955, p. 17-18.

2 E. ir V. Holubovičiai, Gedimino Kalno

Vilniuie 1940 metų kasinėjimų pranešimas (A report about the

excavations in 1940 on the Hill of Gediminas), Lietuvos Praeitis I,

Kaunas 1941, p. 649, 651.

3 J. Puzinas, Gedimino Kalnas.

Lietuviškoji Enciklopedija Vin, Kaunas 1940, p. 1138.

4 W. Kieszkcwski, Dzieje placu

Katedralnego w Wilnie, "Wilno" No. 2, Vilnius 1939, p. 102-104.

s J. Obst, Zburzenie Zamku Dolnego w Wilnie, Litwa i Ruš II, 1912, 55.

« Sobranije drevnych gramot i aktov gorodov: Vilny, Kovna, Trok etc. I,

Vilnius 1843, p. 1 (No. 1).

7 Sobranije etc. o. c., p. 12-20 (No. 14).

s N. N. Voronin, Drevnee Grodno po materialam archeologičeskich

raskopok 1939-1949, Moscow 1954, p. 130.

9 N. N. Voronin, o. c., p. 183-189.

10 P. Sledziewski, Košciol šw. Anny šw.

Bar-bary intra muros castri vilnensn, Ateneum Wileflskie DC, 1933-34,

p. 1-32, and prers informations.

11 J. Kurczewski, Košciol Zamkowy czyli

katedra wilenska etc. II, Vilnius 1910, p. 7 (Privileg of Jcgaila on

10.11.1387).

12 M. Walicki, Cerkiew šw. šw. Borysa i

Gleba na Koložy pod Grodnem, Warsaw 1929; M. Limanowski, W sprawie

kultu Borysa i Gleba w Grodnie (Prace Sekcji Historji Sztuki III),

Vilnius 1938/39, 156 p.; Concerning "echea" (acoustical vases) see:

Lithuanian Encyclopedia VII (1956) 31 p. (Garsintuvas).

12 V. Gidžiūnas, O.F.M., De Fratribus Minoribus in Lithuania

usque ad definitam introductionem obser-vantiae (1245-1517), Romae 1950.

14 Z. Ivinskis, Trakų Galvės ežero salos pilis (The castle

of Trakai on the isle of the lake Galve), Vytauto Didžiojo Kultūros

Muziejaus Metraštis I, Kaunas 1941, p. 160.

15 E. Gall, Danzig und das Land an der Weichsel, 1953, p. 45.

16 J. Borovskis, Trakų salos pilis, kaip tvirtove ir

Didžiojo Kunigaikščio rezidencija, atlikti] konservacinių darbų

šviesoje (The isle-castle cf Trakai, as the fortress and the residence

of the Great Duke, in the light the works of conservation), Vytauto

Didžiojo Kultūros Muziejaus Metraštis I, Kaunas 1941, p. 211-7.

17 M. Morelowski, Zarysy syntetyczne

sztuki wi-lenskiej od gotyku do neoklasycyzmu, Vilnius 1939, p. 19.

18 J. Remeika, Der Handel auf der Memel

von Anfang des 14. Jahrhunderts bis 1430, Diss. Kiel 1927, p. 54-57

(the text cf this privilege).

19 P. Rėklaitis, Die gotische St. Annenkirche in

Vilnius. Eine kunstgeschichtliche Frage im Osten, Commentationes

Balticae II, Bonn 1954, p. 25.

20 J. FijaJek, Opisy Wilna až do polowy

wieku XVII-go, Ateneum Wilenskie II, Vilnius 1924, p. 144.

21 A. Szyszko-Bohusz, Warowne zabytki

architek-tury košcielnej w Polsce i na Litwie, Cracow 1914.

22 J. Klos, Wilno, Przewodnik

krajoznawczy, Vilnius 1929, p. 188.

23 W. Tatarkiewicz, Z dziej6w gmachu

universy-teckiego w Wilnie, Ksiega Pamiątkowa ku uczeniu CCCL rocznicy

založenia i X wskrzeszenia universy-tetu wilenskiego, I, Vilnius 1929,

p. 77-83.

24 H. Kairiūkštytė-Jacyniene, Pažaislis,

ein Ba-rockkloster in Litauen, Kaunas 1928, p. 137, 148.

25 M. Morelowski, Znaczenie baroku

wilefiskiego XVIII stulecia, Vilnius 1940, p. 22.

26 P. Galaune, Vilniaus meno mokykla (The

Art-school of Vilnius), Kaunas 1929, p. 70.