Managing Editor P. V. Vygantas

|

www.lituanus.org |

|

Copyright

© 1957 Lithuanian

Students Association, Inc.

September,

1957 No.3(12)

Managing Editor P. V. Vygantas |

|

M. K. ČIURLIONIS

1875 -1911

THE FIRST ABSTRACT PAINTER OF MODERN TIMES

ALEKSIS RANNIT

ALEKSIS

RANNIT,

Estonian poet and art critic. He graduated from the University of

Tartu, Estonia. Since 19i0 lived in Lithuania and worked in the State

Theatre as well as in the Central Lithuanian archives. In exile he

lectured on art history at the Art Institute in Freiburg i. Br. Besides

several verse collections in Estonian, Mr. Rannit has published

numerous translations of Lithuanian poetry and drama. His articles have

appeared in the main European art magazines, such as "Arts," "La

Biennale," "Das Kunstwerk" etc. He is author of a number of

monographies of Lithuanian artists. At present Mr. Rannit is employed

as an expert with the Prints Department of the New York Public Library.

[This article is based

on the lecture presented at the II International UNESCO Congress of the

art critics in Paris]

|

|

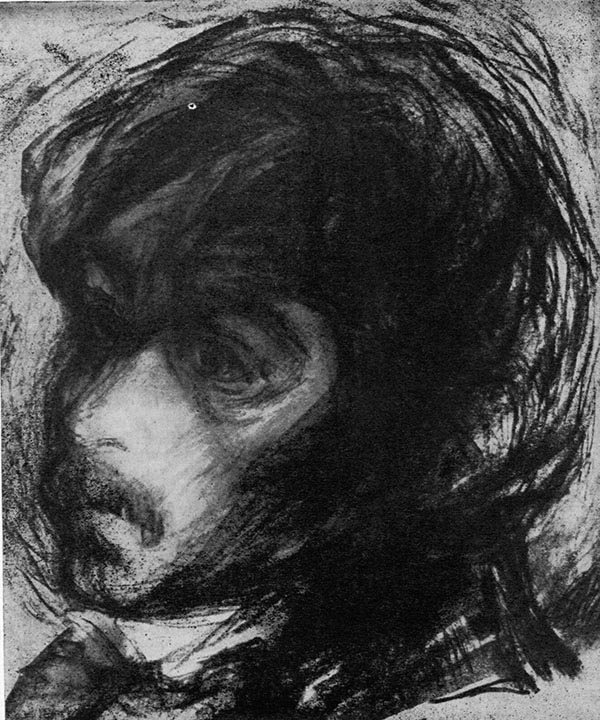

M.K.

Čiurlionis

Drawing

by A. Marčiulionis

|

Baltic art is little known in the Western world. The tragic fate of our peopples and their remoteness from Paris have had a great deal to do with this. From the cultural-historical point of view, the physiognomy of the right shore of the Baltic Sea has so far been little studied and inadequately described. So the spiritual and artistic achievements of our countries remain, in spite of their richness, unfamiliar to the world at large. I would like to draw attention to two artists now working in Paris, who will serve as living examples of the high artistic culture of the Baltic peoples. They are the Estonian graphic artist Eduard Viiralt and the Lithuanian landscape painter Adomas Galdikas. About Viiralt — whose art, I may say, remains unequalled in purity in modern Europe1 — Raymond Cogniat says that he is an accomplished master in the sphere of graphic art,2 while Pierre Mornand emphasizes that in Viiralt's creative work an attempt is expressed to achieve a simple classical perfection," that he "possesses the absolute purity of an Ingres, improved by the humanizing conception of a Chasseriau" and that "his genius will continue to unfold steadily, will find a new means of expression that will once again evoke astonishment."3 Andre Salmon says, "Viiralt must forgive our century the pitiful bunglings of pseudo-masters of graphic art. What other graphic artist of our time has developed to the highest perfection such an absolute harmony between drawing and color scheme?"4 And when we turn to another artist of the Baltic area, the Lithuanian painter Adomas Galdikas, we are in complete agreement with Wal-demar George that he is "an artist of European rank."5 Waldemar George characterizes the work of Galdikas accurately when he says, "The life-giving faith, the capacity to see God's principle in nature and to understand it, leads the painter to a revelation of the atmosphere of Lithuania, permeated with mystery."6

The theme of my essay is precisely a painter who proceeds from a mystical and cosmical perception of the landscape; his name is Čiurlionis, and his work is one of the most significant mani- festations of the art of the North European countries. Čiurlionis was a Lithuanian, and in order to understand him one must know a little about his native land and about the Lithuanian soul. The flat land stretches out endlessly, competing with the sky. Plowland and meadow follow one another in broad expanses. In this majestic flow of fields, hills and forests everything is unity, and there is a cosmic fullness. In this landscape a man becomes conscious of his minuteness and his helplessness. Eternity, still and exalted, watches him and draws him away from the earth. Here freedom is not power but renunciation, a giving up of things. The thirst for immortality, a yearning for the supernatural, is the continuing source of strength in the life and culture of the Lithuanian man. The visionary nature of the landscape, with its peculiar qualities of light, leads a Lithuanian outward over the horizon of the world into the infinite, into the purlieus of the supernatural.

It was Čiurlionis, a son of this landscape, who fully discovered the cosmic Lithuanian soul, a soul that desires no conflict between the material and immaterial worlds or between man and nature. Čiurlionis sought for neither the type of the race nor that of the Godhead but for the absolute, the all-uniting aboriginal essence of things. His eye was attuned to eternity and not to form. His love for the All, the totality of things, was of a strength hardly known before in the North.

Mykolas Konstantas Čiurlionis was born on Sept. 10, 1875, in Varena, Lithuania, and was only 35 when he died on March 28, 1911, in Czerwony Dwor, near Warsaw. He belongs to those elect to whom — as to those beloved of the gods, those, whom Dionysus has possessed — only a brief time is given to record, in a few creative works, the brilliance and the suffering of their souls. In its external aspects, his fate resembles Van Gogh's; he, too, had only six years to complete his life's work in painting before his mind was seized by the night of insanity and death. As a youthful prodigy he was dedicated to a musical career. He graduated from Warsaw Conservatory and wrote a number of significant compositions, of which such symphonic works as "The Forest" and "The Sea" deserve special mention.

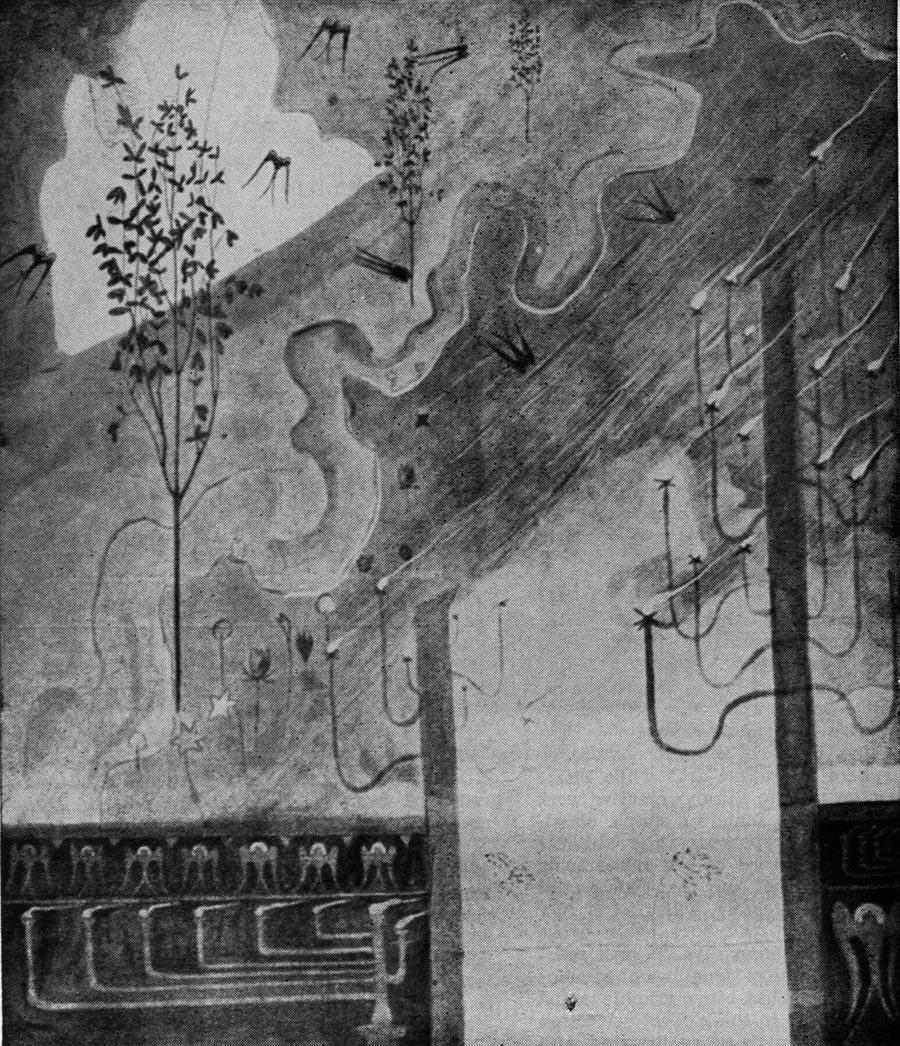

Čiurlionis was already suffering from deep spiritual depression as he entered his 30th year; disillusioned with his musical work, he decided to devote himself to painting. Now the pictorial-musical elements in him were spiritualized into a soulful experience of matter. He attended the Warsaw Art School, but only briefly, since he soon realized that what he wanted to express could not be acquired by learning. He cut short his studies, and remained a self-taught man of genius. Čiurlionis wanted to paint music, but he did not see the meaning and purpose of painting in a sensory-musical expression of the colors, nor was the mystical life of pure color, though it is present in his art, of any greater satisfaction to him. He was searching for a complete synthesis of time and space in painting — that is, for something "impossible." Trained as a musical scholar and a composer, Čiurlionis created his own world of a fantastic sort and constructed his art in purely contrapuntal fashion, as a series of symphonic statements. Thus arose his symbolic serial compositions "The Sea Sonata," "The Spring Sonata," "The Sun Sonata," "The Sonata of Pyramids" and "The Serpent Sonata," in which each work has its own musical characterization, such as allegro, andante, scherzo, finale, etc. There are also the cyclical works, such as "Creation of the World," "Cycle of Animal Life," "The Fairy Tale" and "Fantasy (Prelude, Fugue and Finale)," as well as several isolated, self-contained works.

Only

a few of the Lithuanian painter-composer's works are free-fiowing

compositions, presenting a delicate lyricism of feeling, a sublime

spiritualization of directly perceived impressions of nature. In

general, these are forms that, masterfully transformed into poetry,

acquire a symbolic significance in which a most profoundly Lithuanian

feeling for nature, stemming from mystical sources, finds its

expression. Above all, however, Čiurlionis joined to the beauty of

symbolic influences in the abstract style that he had achieved

something new — a sensitivity for the secret of cosmic Being and fate,

for the merciless invisible powers that ruled him, a sensitivity that

arose from metaphysical experience. Timeless figures and abstract forms

of transcendental beings, emerging from the depths, step upon the

silvery-gray ground. These forms, individually clearly delineated, seem

to wish to intensify the penetrating force of spiritual reflection, to

make themselves grow through contrapuntal and other

"musical-geometrical" repetition in rhythms that resemble one another,

and then to purify themselves again into calm harmonies, until the

whole canvas seems filled with continuous correspondences of harmonious

elements of form.

Čiurlionis worked exclusively in tempera;

since he was too poor to buy good paints, he had to make c?o with

cheap, inferior paints. The tragic consequence is that today, 50 years

after his works were created, they have already lost half their silken

color quality. The works gathered in the Čiurlionis Gallery in Kaunas

are steadily fading; they are "dying away" before they have become

known to the world. Outstanding Russian art critics and poets have

interested themselves in Čiurlionis' creative work. Among them may be

mentioned Vyacheslav Ivanov, Sergei Makovsky, Nikolai Vorobyov,

Chdovsky, Lydie Krestkovsky and Lehman. In 1939 Romain Rolland, a great

admirer of Čiurlionis' art (as he says in a letter to the Russian art

critic Vorobyov), desired to come to Lithuania to write a book about

the artist. This would have given the marvellous painter a worldwide

audience; however, the war prevented the project. It is to be feared

that Čiurlionis will remain merely a legend on the fringe of the

history of art.

|

Villeneuve (Vaud) Villa Olga

Dear Mrs. Čiurlionis,April 10, 1930 . . It is now already fifteen years since I accidently came upon Čiurlionis (in the pages of a Russian magazine which, I think, was called "Apollon") and was literally stunned. "Since then I never stepped, even during the war, to look for ways to get better acquainted with him. It was not easy. Yet I succeded in acquiring two books which had reproductions of his works . . . "Words are powerless to express how much I have been affected by this genuinely magic art which managed to enrich not only painting, but man's vision in polyphony (counterpoints and fugues) and the rhythmics of music as well. To what developments this fruitful invention could lead in wide space painting, in monumental frescoe! It is a new continent of the spirit and Čiurlionis is its Christopher Columbus. "One of ttie characteristic features which astonished me in the composition of many of his paintings, is a view that opens itself toward endless plains from the top of some tower or a dizzyingly high walls. I ask myself: what could have given birth to these impressions in a land like yours which, to my mind, has not supplied him with any motives of height. I imagine that it was the painter himself who experienced such intoxicating dizziness and that feeling of soaring flight which overtakes one before falling asleep ... "I cannot thank you enough for the opportunity you have given me to acquaint myself at last with his music ... In my opinion the most original works are the 7 Preludes and the Fugue. One can feel in them the flow of atmosphere in forests and plains. I desire to hear some day his Symphonic poem "The Sea" . . . ROMAIN ROLLAND

"P. S. . . . Stravinsky has also spoken well to me about the works of Čiurlionis. He said he had one of his paintings . . . "I am still hopeful that some day I will have the opportunity to see your ancient Lithuania, the name of which always implies to me so many mysteries. I extend my fervent sympathy to the heroic land-tillers' nation that was able to preserve, wars and centuries-long suffering not withstanding, its free spirit and its sonorous and highly developed language. |

To consider Čiurlionis a phenomenon of the past, however, would be to do an injustice to his original personality, as well as to the history of art. As the first abstract painter, as the creator of the peculiar sonata form in painting and as symbolist and surrealist, he belongs among the most interesting phenomena of modern painting.

Odilon Redon once called himself "the symphonic painter." This title is an original definition, but so far as this master's creative work is concernedd it is a purely literary one that seems to lack any profound substantiation from a scholarly point of view. As against the claims of this French painter, and the Impressionists as well, it would seem to be Čiurlionis alone so far who is entitled to be called a "musical painter." This name was justly given to him by Lydie Krestovs-ky in her book "La laideur dans l'art" (Ugliness in Art).7

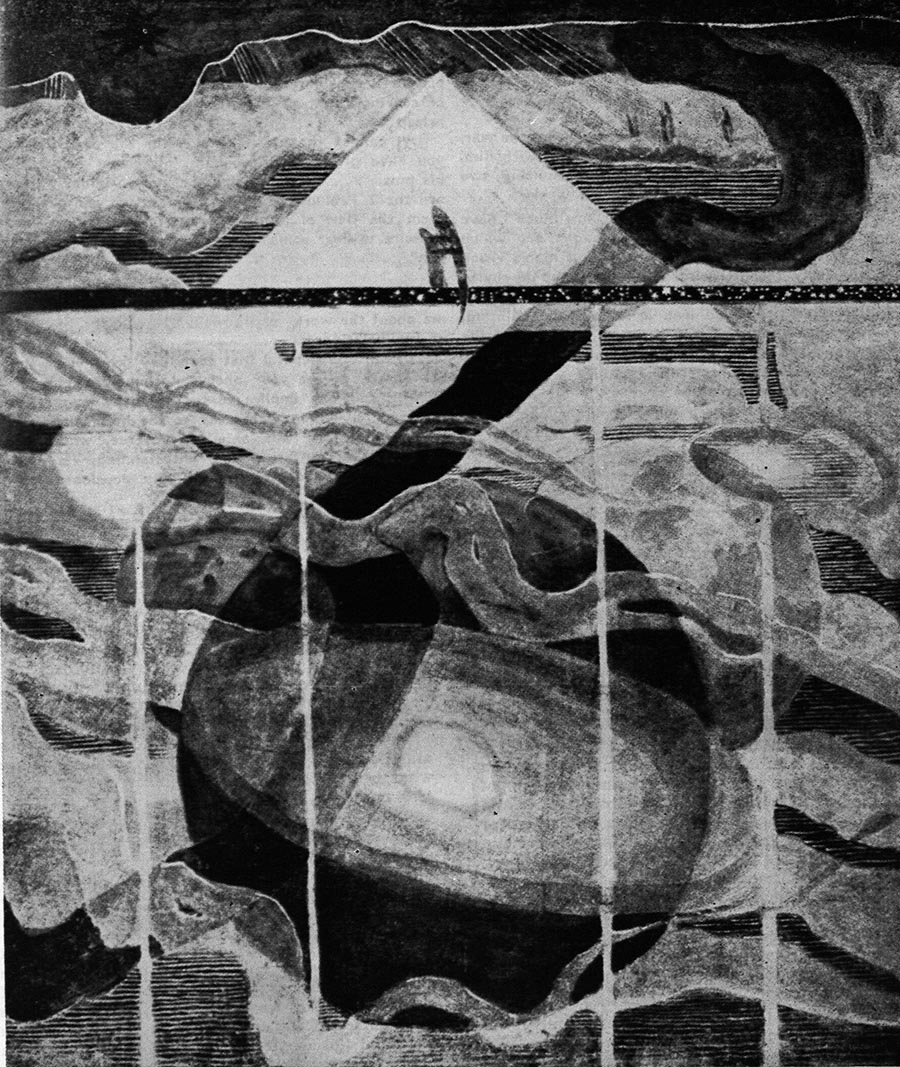

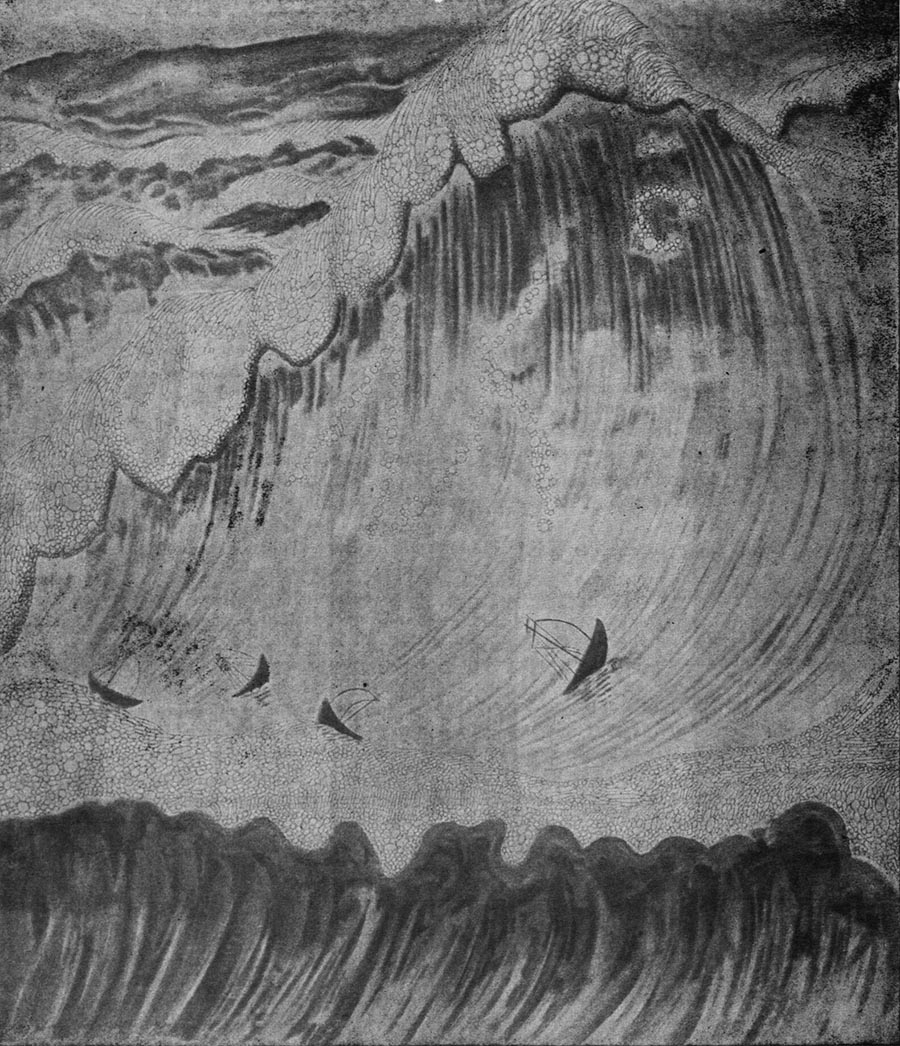

"For Čiurlionis, music formed the metaphysical substratum of the universe," Nikolai Vorobyov wrote. "Čiurlionis attempts to dynamize the picture by anologies to the means employed in music. Rhythmically graduated forms and groups of forms suggest the impressions of music. The tempos and the dynamic values are made visible either through a variety of playfully interwoven motifs, which are organized in zig-zags and which climb and fall diagonally (allegro, scherzo), or through drawn-out horizontal lines and large, calm surfaces (andante). The melody may be represented through the swinging sweep of a line, the tone and the modulation through the general tone color and through the deviations from it."8 As far as the musicality of the color is concerned, Čiurlionis sought for it least of all. As I have already pointed out, he constructed his works in purely contrapuntal fashion, as a series of symphonic statements; for this reason I permit myself to call him a true "symphonic painter," a musical scholar who mastered the medium of painting and created a form of painted sonata and painted fugue — a form that gave plastic, linear and color expressions to musical impressions and that arrived at a set of musical-geometrical laws. In Čiurlionis there is the poetry of powerful, exalted, demonic arts, the poetry of tempests, of sea storms. The central role, however, is always played by the concept of a specific rhythmical-musical arrangement. Here is realized for the first time in the history of art the symphonic concept in painting.

The artist wishes to free himself finally from all elements of contradiction, in order to convey his spiritual experience, as in music, purely by means of art — that is, through a specific sequence of manifestations of the movement of forms. The artist ecstatically dissolves himself in the totality of the universe, submerges himself in the act of creation. It is an ecstasy simultaneously of the ear and the eye, in which we become exalted; it is a state cf dream, a moment of lethargy, a spirituality unequalled in art.

What is presented in Čiurlionis' paintings has little or nothing to do with experience (tradition); that which is perceived becomes an object not through a sensual awareness of a thing but through an act of the imagination, and its natural essence, striving toward unity, is formulated as a mystery. Here, therefore, the ideas of a rigorous musician and those of a mystic coalesce, since what is formed here is the essence not of an object but of a perception.

The essential things that have up to now been said about Čiurlionis have come from Vyacheslav Ivanov, the important Russian philosopher and poet who died as an exile in Italy in 1949. In his study "Čiurlionis and the Synthesis of Arts" this high-ranking man of letters wrote:

The work of Čiurlionis achieves an exalted meaning for the history of future art through its cosmic and transcendental fulfillment of things. For we cannot fail to note that the pathos of this artist is not a pathos of dream and illusion. It is a profession of faith in an objective world-view; it is at the same time a confession of the inner spectacle, a declaration about those spiritual tensions of human beings that Dante has called spiriti del viso.

We have arrived at the boundary over which Čiurlionis passes into the world of the abstract.

Kandinsky, who used to be among us in Estonia, teaching law at Tartu University, painted his first abstract painting in 1911. Kandinsky first became acquainted with the work of Čiurlionis through the magazine Apollon, which in 1911 reproduced a series of works by the Lithuanian painter, together with an evaluation by the famous critic Sergei Makovsky. Later he saw and was profoundly impressed by the great memorial exhibition of Čiurlionis' paintings in Moscow. I repeat that Kandinsky painted his first abstract picture in 1911; by 1904, however, Čiurlionis had already painted pictures that today must be considered abstract or semiabstract.

It was in this and the following year that the Lithuanian painter created the great cycle (14 pictures in all) entitled "Creation of the World." In these works objects lose their compulsive reality and a dreamlike reflection of the inner life comes to the fore. It is the mystique of the Cosmos, and not of the individual, that is given us here. Čiurlionis paints the spiritual element of the creation of the world. He thinks of the identity of the infinite and tries to show visually how everything that is separate has been in this process a consequence of the whole. We emerge from the chaos of primeval darkness to greet the ecstatic flowering of nature. The forms of the cycles "Summer" and "Winter," both painted in 1907, are even barer; they can be regarded as classical examples of abstract art. "In 'Winter'," N. Vorobyov writes, "a profound immersion in the peculiar manifestations of light of the Northern winter nights, in the magical mood of a world of snow bathed in the d m light of the moon, is linked with the play of abstract forms and irrational outlines of the external world, as was later attempted in similar fashion by Paul Klee and Kandinsky... The present acquires multiple meanings; one and the same form appears simultaneously as star, flower, flame and sncwflake."10 In his important "Sonatas," Čiurlionis also represented the unifying force in nature, which often exists beyond any material details. This can be seen most clearly m "The Sonata of Stars." But, in contrast to his follower Kandinsky, Čiurlionis does not struggle against nature; quite contrary: In his love for her he establishes the pure, the abstract character of her forms, her metaphysical "nakedness"; he constantly transmits an experience of objects that is full of symbolism, as well as being a metamorphosis of phenomena.

As I have already mentioned, Čiurlionis was self-taught. Moreover, he was totally unfamiliar with modern French art. It was a fateful hour of history that linked him with the other renewers of art. At that time he, too, had created works that (to play with the terminology of cubism) aspire to the perfection of the crystal. Consider, for instance, works like the andante of "The Sun Sonata" (1907) and the andante of "The Serpent Sonata" (1908), which appear to us as geometrical compositions that were extraordinarily bold for their time.

Čiurlionis,

as the founder of the abstract form, as a painter-musician and as an

artist who renounced the old dimensions and who solved the formal

problems of composition, is an astonishing phenomenon. But it is his

innermost expression rather than his formalistic daring that makes him

a great painter. He demonstrates to us that the highest quality of a

work of art is its content, its spiritual substance — a metaphysical

essence, a mystical ingredient of existence, something life-spending.

Every object becomes for him the expression of his secret will. Every

form is conditioned by the personal will, which restlessly destroys

itself in everlamagine that it was the painter himself who experienced

such intoxicating dizziness and that feeling of soaring flight which

overtakes one before falling asleep ...

"I

cannot thank you enough for the opportunity you have given me to

acquaint myself at last with his music ... In my opinion the most

original works are the 7 Preludes and the Fugue. One can feel in them

the flow of atmosphere in forests and plains. I desire to hear some day

his Symphonic poem "The Sea" . . .

ROMAIN ROLLAND

"P. S. . . . Stravinsky has also spoken well to me about the works of Čiurlionis. He said he had one of his paintings . . .

"I

am still hopeful that some day I will have the opportunity to see your

ancient Lithuania, the name of which always implies to me so many

mysteries. I extend my fervent sympathy to the heroic land-tillers'

nation that was able to preserve, wars and centuries-long suffering not

withstanding, its free spirit and its sonorous and highly developed

language."sting labor. In his work we constantly meet this whole

torment of dissatisfied search. Everywhere is hope and struggle,

everywhere yearning, everywhere the great question and nowhere the

answer, everywhere the struggle of the living and nowhere the final

aim, the end. The principle of creation is constantly turned into a

tragic principle. For Čiurlionis the whole of nature is the fata

morgana of some god, and he paints the god's power as a visionary,

sensual idea. In this divine-demonic Cosmos man plays at best a rather

insignificant role — he is open to the caprice of nature. The "Serpent

Sonata" andante conceals an experience of shock, of worldwide fear, of

horror. Man stands at the brink of the abyss, filled with yearning for

the far-off light. Salvation is impossible. The serpent — the

catastrophe of the spirit — will overpower him. This picture and

Picasso's "Guernica" are the most shattering documents of our time,

presenting the whole situation of modern man to us with astounding

force.

magine that it was the painter himself who

experienced such intoxicating dizziness and that feeling of soaring

flight which overtakes one before falling asleep ...

"I cannot

thank you enough for the opportunity you have given me to acquaint

myself at last with his music ... In my opinion the most original works

are the 7 Preludes and the Fugue. One can feel in them the flow of

atmosphere in forests and plains. I desire to hear some day his

Symphonic poem "The Sea" . . .

ROMAIN ROLLAND

"P. S. . . . Stravinsky has also spoken well to me about the works of Čiurlionis. He said he had one of his paintings . . .

"I

am still hopeful that some day I will have the opportunity to see your

ancient Lithuania, the name of which always implies to me so many

mysteries. I extend my fervent sympathy to the heroic land-tillers'

nation that was able to preserve, wars and centuries-long suffering not

withstanding, its free spirit and its sonorous and highly developed

language."

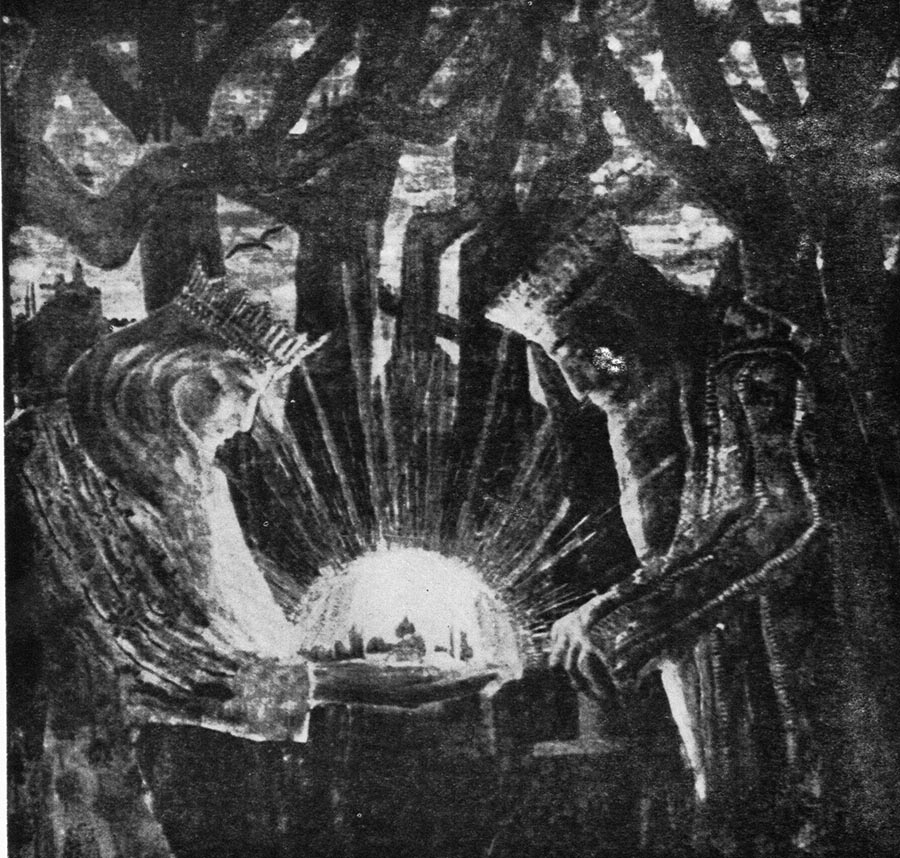

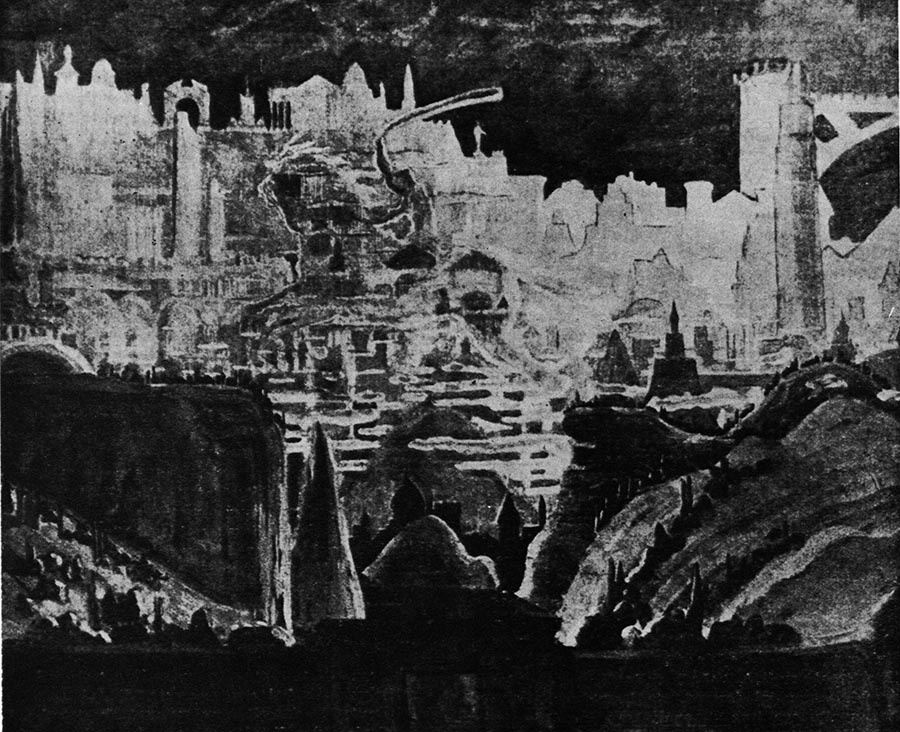

Tale of Kings

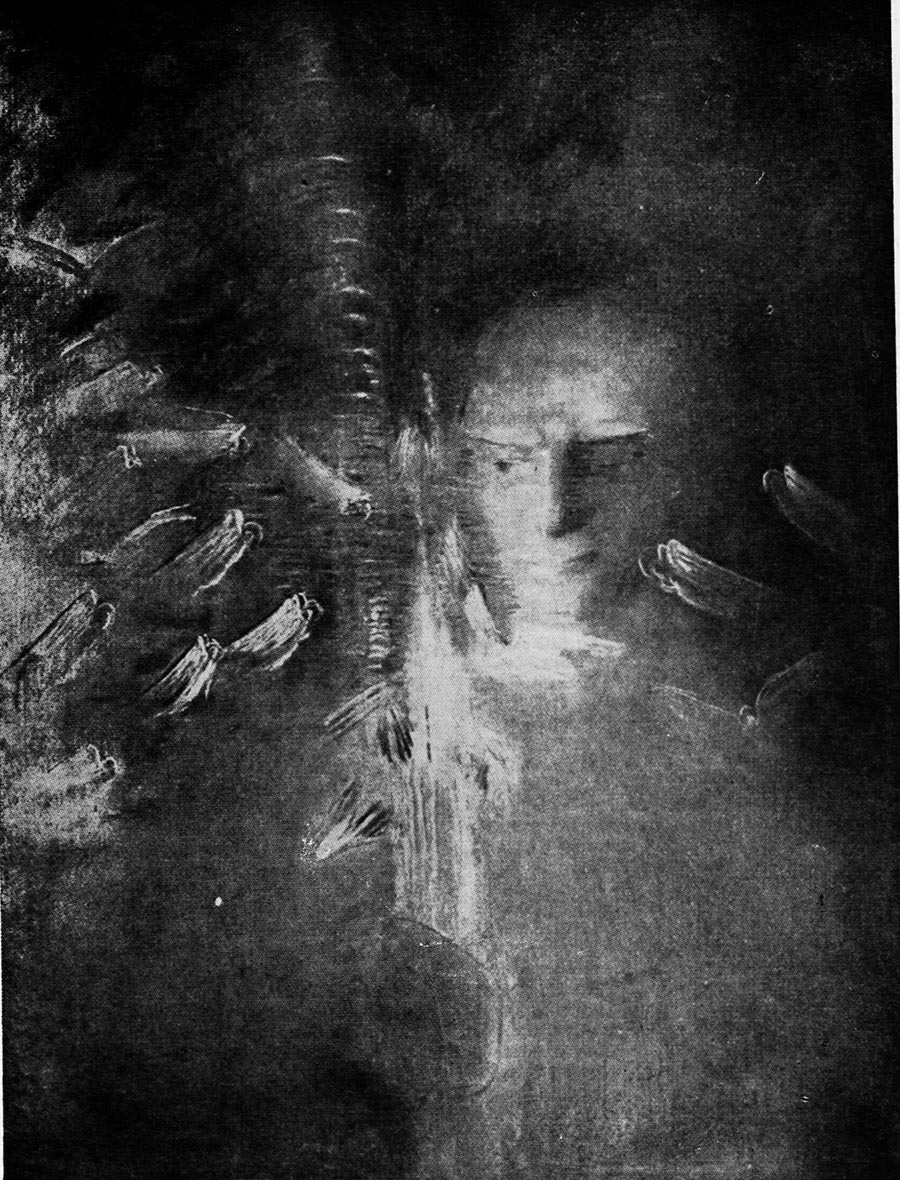

Hope

The Spring Sonata (Scherzo)

|  |  |

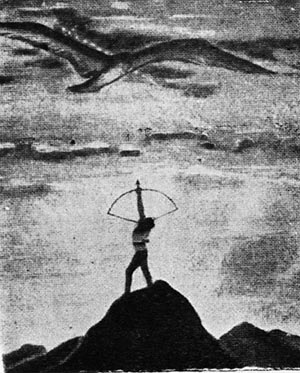

| The Archer | The Virgin | The bull |

| Signs of the Zodiac | ||

The Sonata of Stars

The Sea Sonata

The Knight