December, 1958 Vol. 4, No. 4

Managing Editor P. V. Vygantas

|

www.lituanus.org |

| Copyright

© 1958 Lithuanian

Students Association, Inc. December, 1958 Vol. 4, No. 4 Managing Editor P. V. Vygantas |

|

VINCAS KUDIRKA

DR. VINCAS MACIŪNAS

DR.

VINCAS MACIŪNAS has taught Lithuanian literature at the Universities of

Kaunas and Vilnius and was in charge of the university library in

Vilnius. Later associate professor at the Baltic University in

Hamburg-Pinneberg, Germany, he is now working in the library of the

University of Pennsylvania in Philadelvhia, Pa.

|

On December 31, Lithuanians will

celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Vincas Kudirka, their

great patriot and famous writer and author of their national anthem.

Commemorative meetings will be held in many Lithuanian colonies in the

free world, and the Lithuanian press is already carrying articles about

Vincas Kudirka. His name has been honored by all Lithuanians for many

decades. When Lithuania gained her independence, Kudirkas works were

read and studied by thousands of Lithuanian students; statues of him

decorated many squares and parks and portraits of him were displayed in

many official buildings. Numerous streets were named for him, and

Naumiestis, the town where Kudirka died, was renamed Kudirkos

Naumiestis.

In order to gain a better understanding of Vincas Kudirka's

significance to the Lithuanian nation, we must first briefly survey the

times in which he lived. The Lithuanians had been suffering from

Russian domination since the end of the 18th century. That domination

became increasingly severe with each unsuccessful uprising, and after

the revolt of 1863 the Russian government inflicted such terrible

repressions on Lithuania that the governor-general, Muriaviev, became

known to history as "the hangman." The Russian government did not stop

at hangings and deportations, however; it attempted to root out

completely any possibility of future unrest. Lithuania was to be

completely Russified, and a thoroughgoing Russification program was

instituted. Russian colonists were settled on lands confiscated from

the revolutionaries; only Russians were appointed to government posts;

all private schools were closed and children had to attend Russian

schools. Lithuanian cultural life was greatly hampered and the Russian

Orthodox Church received open support, while the Catholic Church, which

exerted a great influence on the people and could thus have interfered

effectively in the Russification program, was subjected to constant

supervision. This policy toward Lithuania was in line with the general

policy toward non-Slavonic people, which was inspired by Slavophiles

and pan-Slavists. Even more drastic measures were adopted in Lithuania,

however: Lithuanians were forbidden to use the familiar Latin alphabet

and were told to use the Cyrillic one. It was hoped that once the

Lithuanians became used to the Cyrillic letters, they would become used

to Russian books and the Russian language and would eventually become

completely Russian. On this score, the Russian senator Miliutin once

cynically remarked that the Russian letters would finish what the

Russian sword had begun.

But the Russian government, to its own surprise, had miscalculated. In

spite of the fact that during the forty years 1865-1904, not even

primers and missals could be printed in the Latin alphabet in

Lithuania, books in the Cyrillic alphabet that were supplied by the

Russian government were not accepted. Only about sixty of these books

were published during this period, and even these were destined to

mildew in government warehouses. Meanwhile, since acceptable literature

could not be published at home, they were published in East Prussia,

where a part of the Litnuanian nation was living under German rule.

This material was smuggled across the border and distributed throughout

the country. At first, books of a general nature were primarily

published, but eventually nationalistic periodicals made their

appearance. The year 1883 marked an epoch in the Lithuanian national

revival, since in that year the first issue of 'Aušra' (The Dawn")

appeared. This newspaper of nationalistic inspiration was soon joined

by a number of others. It is true that, because they were constantly

persecuted by the government and were forced to circulate underground,

these newspapers were small in size, but their significance to the

Lithuanian nation was great. In articles beyond the reach of the

official censors they explained to the people their rights and

privileges, threw light upon the designs of the Russian government and

encouraged the people to resist. They urged the idea of nationhood and

were successful in arousing the passive and conservatively inclined

peasant class into a nation. And if Aušra" had only a handful of

patriotic contributors, several decades later the 1905 Congress of

Vilnius welcomed some two thousand people who courageously demanded

autonomy for Lithuania.

The struggle for a national literature was not easy, for the Russian

government did not hesitate to use against a defenseless Lithuania a

large police force, the courts and the administration. The last

mentioned became the chief punitive agency and dealt out severe

punishments: long prison terms or even exile to Siberia. The courts

were less frequently resorted to by the government, for their sentences

were lighter. In this way what began as a ban on the press ended as a

total persecution of the Lithuanian nationalist movement. Eventually

the Russian government was forced to concede defeat and to admit that

the press ban not only failed to achieve its aim but actually worked

contrary to Russian interests, in as much as it revolutionized the

Lithuanian nation. In 1904 the ban was lifted.

The forty-year period is a heroic time in Lithuanian history, one that

Lithuanians recall with pride. Two heroic types arose during this

period that became national symbols to future generations. The first

was the man who smuggled literature across the heavily guarded border.

In doing this, and in spreading the writings throughout the land, he

was risking his life. He was pursued and persecuted and not

infrequently punished by exile from Lithuania. But he never lost

courage, and ultimately he was the victor over the huge Russian

administration. The second type was the writer himself, also

persecuted, hiding under a pen name, always subject to searches, often

arrested and imprisoned or deported or, because of the difficult

conditions of his life, an early prey to tuberculosis. In this second

group we find Vincas Kudirka.

Vincas Kudirka was born on Dec. 31, 1858, in the county of Vilkaviškis,

in southwestern Lithuania. From his father, an able and respected

farmer, he inherited a strong character and a clear mind, while from

his mother, who excelled in singing and story-telling, he received his

artistic tendencies. While Kudirka was still in high school he was

known for his interesting drawings and as a singer and a talented

musician (he later arranged a number of Lithuanian folk songs and

dances), as well as a gifted story teller who was even known to write

verses. It would have been difficult to foresee that this lively and

witty youth, who knew how to enjoy himself and was a good dancer and

popular with the fair sex, would grow up to be a determined fighter for

national freedom, a man with a strong sense of duty, an influential

leader of the Lithuanian nation all the more difficult since at this

time Kudirka (like the greater number of Lithuanian intellectuals, who

because of historical circumstances were still strongly under Polish

cultural influence) held himslf aloof from the nationalist movement.

When Kudirka graduated, he did not go to Moscow to study, although a

large group of Lithuanian students had gathered there, but rather to

Warsaw. He enrolled in the faculty of history and philology, but a year

later he switched to medicine.

While Kudirka was studying in Warsaw, and especially during his

holidays at home, he heard more and more about the growing nationalist

movement. Among his former high school classmates was an active

patriot, Jonas Jablonskis, who later became a noted linguist.

Jablonskis was then a student in Moscow, and he wrote Kudirka a fiery

patriotic letter. It was "Aušra", however, that made a very special

impression on Kudirka. He himself has described the moment: "Quickly I

leafed through "Aušra" and I do not remember all that was happening

within me...I only remember that I stood up, bowed my head, afraid even

to look upon the walls of my room... It seemed that I heard the voice

of Lithuania speaking, accusing and forgiving at the same time: And

you, pridigal, where have you been up-to now? Then I became so sad that

I laid my head on the table and wept. I grieved for the hours that had

been irretrievably erased from my life as a Lithuanian, and was ashamed

that for so long I had been a degenerate... After that my breast was

filled with a quiet warmth, as if I was gaining new strength... It

seemed that I had grown up all at once, and that this world had become

too narrow for me... I felt myself mighty and powerful: I felt that I

was a Lithuanian." And Kudirka continues: "Soon I became engaged to

Lithuanian literature, and to this day I have not deserted my

betrothed."

In 1889, Kudirka and some friends founded "Varpas" ("The Bell"), a

monthly of liberal tendencies which ceased publication in 1905. This

paper was widely read in Lithuania, and it exerted a great influence in

forming Lithuanian national and political opinion. It attracted many

influential contributors noted Lithuanian writers such as žemaite,

Lazdynų Pelėda, Gabriele Petkevičaitė and Jonas Biliūnas; Antanas

Kriščiu-kaitis, future president of the Lithuanian Supreme Tribunal;

Kazys Grinius, a future president of Lithuania; Petras Leonas, a

well-known jurist and later dean of the law faculty of the Lithuanian

University; Jonas Jablonskis, the so--called "Father of the Lithuanian

Standard Language," and many others. But the principal contributor to

"Varpas" and unquestionably its very soul was Vincas Kudirka. Upon

"Varpas" he left the imprint of his exceptional personality; to it he

consecrated all of his talent and all of his strength, which even then

was beginning to fail him; he had an incurable disease that brought an

end to his industrious life on Sept. 6, 1899.

It may be that he inherited his weakness for tuberculosis from his

mother, who died of it when he was only ten. Unquestionably the

financial difficulties of his Warsaw days contributed to the weakening

of his health. Another possible factor was the Russian prison in

Warsaw, where he spent some time in 1885. His first hemmorhage came in

1889, the year he graduated from the university. It was not easy for

him to earn a living as a doctor, as his own health was steadily

deteriorating. In 1894 he went to the Crimea in search of a cure, but

he soon returned because of insufficient funds. In 1895 he was arrested

by the Russian police for his patriotic work and was imprisoned for a

short time in Kalvarija. In the fall of the same year he went back to

the Crimea, from which he returned in 1896 already a sick man who spent

most of his time confined to bed. He relinquished his medical practice

but did not sever his connections with "Varpas.' He settled in the

border town of Naumiestis, so that he might more easily supervise

"Varpas," which, like most Lithuanian publications of the time, was

being published in East Prussia. Kudirka had to be extremely cautious

in his work, since he was suspected by the police. He wrote on very

thin paper, which could easily be burned in the flame of a candle

should the police knock on his locked door. Thus Kudirka in a room of

his small house, rarely visited by anyone (other Lithuanian patriots

avoided frequent visits so as not to arouse the suspicions of the

police), confined to bed by his illness wrote his many articles, read

proofs and supervised the publication of his newspaper. His words in

printed form spread throughout the entire country, arousing a national

consciousness and courageously condemning the cruel actions of the

Russian administration. As a doctor himself, Kudirka well knew that

death was approaching, but this did not lead him to despair; rather, it

encouraged him to work with greater speed. In fact, it is amazing how

Kudirka calmly mentions his approaching death in his letters, as if in

passing. To quote from a letter written to Mykolainis, the publisher of

some of his works, on July 15, 1898; "This fall, winter and spring I

was confined to bed. Now I can walk, but only in my room. I may survive

until winter." He was not concerned with his ebbing life, only with his

work. In his last letter to Mykolainis, written immediately before his

death, he still said, "The only thing that worries me is that I may not

finish The Black Earth; perhaps I will finish it, even though death is

watching me very closely." The novel referred to in the letter, which

was written on Oct. 10, 1899, was a work of the Polish writer M.

Rodziewiczowna that Kudirka was translating. He did not complete the

translation; he died within the month.

Kudirka's friends were deeply moved by his iron will and his diligence.

Jonas Staugaitis, future president of the Lithuanian parliament, writes

in his memoirs: "Whenever I happened to visit Vincas Kudirka, I was

always impressed by his appearance: in a small room, on a bed, lay a

lean man, almost like a shadow, with a strong gigantic will and burning

eyes, and always writing and writing." No less moving was his pure

idealism, his complete disregard for the poverty to which he, a sick

man, had come. He did not write for personal profit, only to help his

country. He once wrote to Mykolaitis: "Since you are aware of my

financial status, you will not be surprised at what follows. I would

appreciate it if you would forward some money for the second volume of

Kanklės. I will not specify the amount but leave it up to you to

decide, with my work in hand and according to your means, how much you

can pay me. Know beforehand that no quarrel will arise between us on

this account and that there will be no dissatisfaction on my part

what you can spare will suffice me. And if, after figuring things up,

you can send nothing, that too will be fine." The work referred to in

this letter is a collection of folk songs that Kudirka had harmonized.

Kudirka's collected writings were published in six large volumes in

1909. He was perhaps most influential through the many polemical

articles he wrote for "Varpas"; they appeared in each issue and

constituted the section known as Tėvynės Varpai ("The Bells of the

Fatherland"). Kudirka reacted to the various positive and negative

aspects of life in Lithuania with the sharp insight of a talented

journalist and the zeal of a patriot. But Kudirka did not arouse his

readers as a contributor to the commercial press does, through

sensational news stories; rather he aimed at educating the public. He

wrote, "Lithuanians must know Lithuania. Each one of us must know where

a Lithuanian weeps, where he is happy, where poor and where rich, where

he is abandoned and oppressed, where free and happy, in order that we

may know who among our brothers needs help, and who can help us; we

must know the feelings, thoughts and works of all Lithuanians, so that

it will be clear on whom we may rely to defend the fatherland and to

bring it happiness."

Kudirka's journalistic works clearly show his talent as a writer and

his deeply patriotic spirit, which now rejoices in the event it

describes, now laments it, now ironically mocks or is filled with anger

against observed evils. In particular, he wrote many angry words

describing the wrongs inflicted upon the Lithuanian nation by the

Russian government. The notorious Slaughter of Kražiai occured in 1893

when government Cossacks savagely dispersed a crowd of farmers who had

gathered to defend a Catholic church against a government order that it

be closed. Kudirka, disregarding the danger that the author of such an

article faced should he be exposed, wrote in great indignation: "The

hair stands up on one's head, the blood freezes in the veins when one

thinks of Kražiai. To think that such things could happen in a time of

humanitarianism and toleration of all kinds, in a time when societies

are being founded to discourage the breaking off of twigs from trees,

for preventing cruelty to animals and for oulawlng the slave trade in

savage lands. Do-gooders! Do not hurry to provide protection for the

trees and animals of Europe, for in this very Europe there are still

human beings who are not free from torture! Do not look to Africa, as

if you believed there are no slaves in Europe! Do not forget that in

Europe there is Muscovy behold the land called Lithuania, suffering

under the Muscovites; you will find slaves here, crying in a more

pitiful voice than those among the savages. And truly, first show your

good will in Europe; leave Africa for the future, as a lesser evil. In

vain might we search the whole world, we should never find deeds more

savage than those in Kražiai. Such atrocities are only possible under

the protection of the throne upon which Ivan Grozny) sat. You Neros of

ancient times, tremble before the White Tsar he has surpassed you!'

Kudirka displays the same attitude toward the Russian government in his

popular satirical stories Viršininkai (the Chiefs), Lietuvos tilto

atsiminimai (Reminiscences of a Lithuanian Bridge). Vilkai (The Wolves)

and Cenzūros klausimu (On the Question of Censorship). In these stories

he sharply derided Russian officials in Lithuania as being ignorant,

corrupt and drunkards, oppressors of the people and persecutors of the

book smugglers.

Kudirka was concerned with enriching Lithuanian literature, and he left

to the Lithuanian reading public translations of several world literary

masterpieces: Schiller's Wilhelm Tell and Die Jungfrau von Orleans,

Byron's Cain and others.

Kudirka also wrote a number of poems. His poetry is social in content

and mirrors his humanitarian spirit. One of his poems was destined to

become especially popular, and it eventually became the Lithuanian

national anthem: This is his eight-line poem "Lietuva, Tėvyne mūsų

("Lithuania, Our Fatherland'), which was published in "Varpas" in 1898

along with the music, which he also wrote. Therefore this year also

marks the 60th anniversary of the Lithuanian national anthem.

In the poem Kudirka recalls Lithuania's past, from which the present

should draw its strength; he exhorts his countrymen to follow in the

path of virtue and work for the good of Lithuania; he hopes that the

sun will disperse the present darkness and that light and truth will

guide Lithuanian footsteps, that love for Lithuania will burn in her

people's hearts and that unity will flourish. As we see, we find

expressed here the same social and patriotic ideals that inspired all

his work. It might be noted that this poem lacks the somewhat

imperialistic note of aggressive designs on foreign territory that

characterizes some national anthems.

Kudirka's song quickly became popular in Lithuania, and it was sung so

frequently on various patriotic occasions that it soon gained the

respect usually shown a national anthem. At the same time it aroused

the hostility of the Russian government. The first act of persecution

occured under singular circumstances that reveal the brutishness of the

Russian administration. On the night of March 2, 1903, a worker in the

pay of the city police mutilated the words of the anthem, which appear

on Kudirka's monument in the Naumiestis cemetery. Later, some years

before World War I, the government prohibited the singing of the anthem

during public concerts. Such acts could not eradicate the song from the

people's memory, of course, and after World War I it was made the

official Lithuanian national anthem. One can easily understand why it

was again banned by the Soviet government following the forcible

incorporation of Lithuania into the U.S.S.R. in 1940. Again, government

orders did not suffice to make the people forget their anthem, and even

today It is a source of patriotic inspiration. Following Is an

interesting account by a woman who had been deported to Siberia,

returned to Kaunas, and in 1957 was able to reach Austria. She

describes a young people's demonstration that took place in Kaunas on

Lithuanian Independence Day (February 16) in 1957: "At ten o'clock...we

went home. I live, as I have mentioned, next to the executive

committee. Above my apartment is a student dormitory. The students were

indescribably noisy today, and I could not get to sleep. Old Lithuanian

songs were being sung again and again. Suddenly a very loud commotion

woke me. It was midnight. The national anthem was being sung on the

Avenue of Freedom. Putting on my coat and forgetting all danger, I

rushed out to the street. In the darkness I saw a mass of people. O

God, they were all youths. They could not confine them under house

arrest. Singing the national anthem, they advanced on the executive

committee. I was moved by the clearly sung words: 'Lithuania, our

fatherland...' Only on strange occasions is the anthem sung." ("Į

Laisvę' (Toward Freedom), No. 15, Brooklyn, N.Y., 1958.)

And so we see that even today the words that Kudirka wrote 60 years ago

are not only being sung in the free world but are also heard in

occupied Lithuania, like a clear symbol of a free and independent

Lithuania.

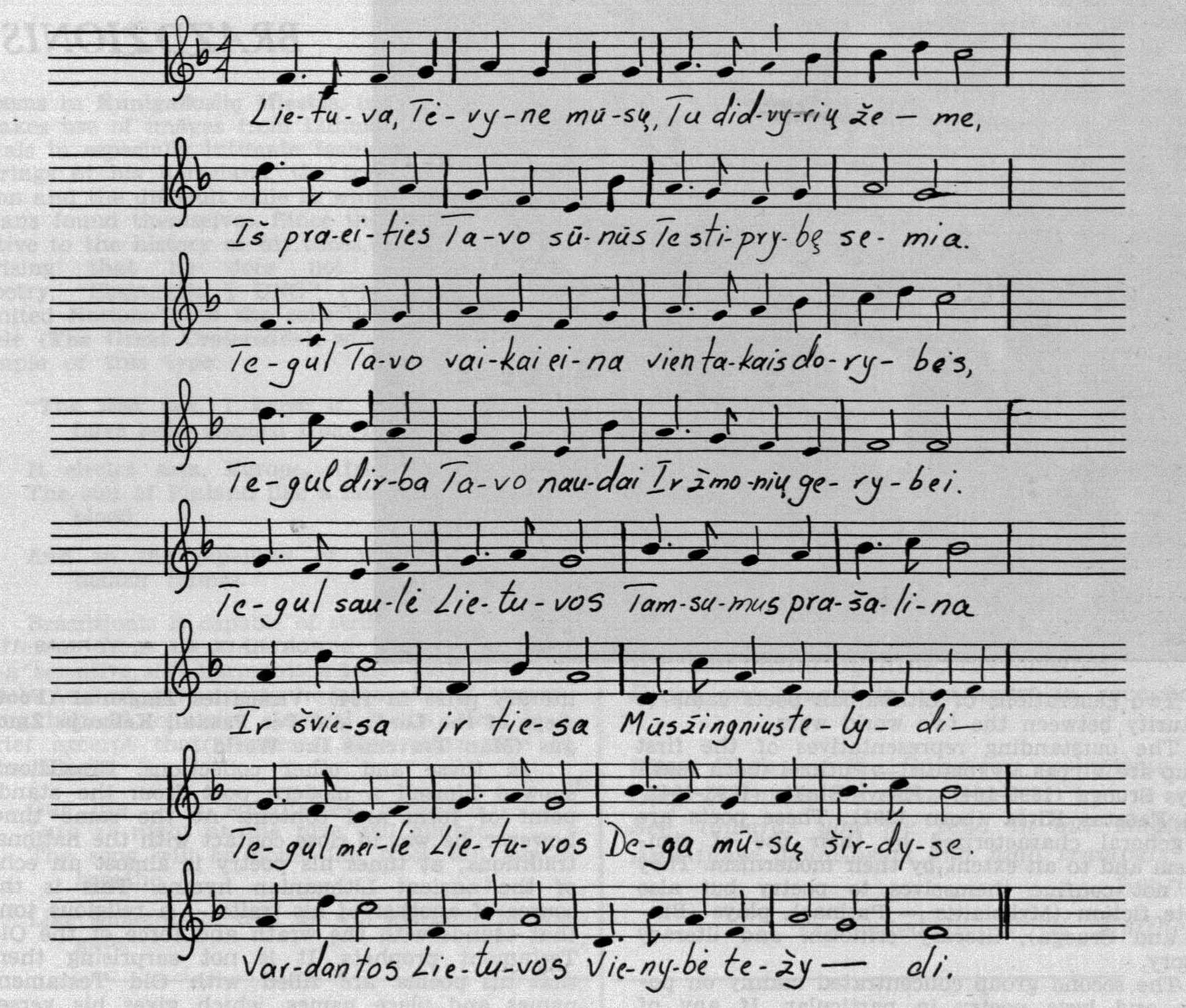

| LITHUANIAN

NATIONAL ANTHEM Words and Music by Vincas Kudirka |

|

|

|

| ORIGINAL WORDS | ENGLISH TRANSLATION |

|

Lietuva, Tėvyne mūsų

Tu didvyrių žeme, Iš praeities tavo sūnūs Te stiprybę semia. |

Lithuania, land of

heroes

Thou beloved fatherland From the glorious deeds of ages Shall thy sons take heart. |

|

Tegul tavo vaikai

eina

Vien takais dorybes, Tegul dirba tavo naudai Ir žmonių gerybei! |

Let thy children,

day by day,

Stride upon the virtuous way Let them labour for thy glory And the good of man. |

|

Tegul saulė Lietuvos

Tamsumus prašalina Ir šviesa Ir tiesa Mūs žingsnius telydi! |

May the sun of

Lithuania

Clear the darkness of the night, And may light and may truth Guide our steps aright. |

|

Tegul meilė Lietuvos

Dega mūsų širdyse, Vardan tos Lietuvos Vienybė težydi. |

May the love of

Lithuania

Flame forever in our hearts In the name of Lithuania Let unity reign. |