December, 1958 Vol. 4, No. 4

Managing Editor P. V. Vygantas

|

www.lituanus.org |

| Copyright

© 1958 Lithuanian

Students Association, Inc. December, 1958 Vol. 4, No. 4 Managing Editor P. V. Vygantas |

|

THE WORLD LITHUANIAN COMMUNITY

On the 28-31 of August, the World

Lithuanian Congress took place in New York City. Concurrently a

representative exhibition of Lithuanian art and a chamber music concert

were presented, at the Riverside Museum; while in Carnegie Hall the

combined forces of four choires, soloists and a symphony orchestra

performed. Thousands of Lithuanians from the U.S.A. and other Western

countries gathered in New York City for the occasion. 112 official

delegates to the congress represented Western countries having

substantial Lithuanian colonies, including the United States, Canada,

England, Australia, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Germany,

France, Italy and others. In all these countries Lithuanians have

already been organized into national communities. And with this

congress the process of welding these national groupings into one World

Lithuanian Community reached its conclusion. In view of this occasion

we would like to acquaint our readers with the reasons for the

existence of the Lithuanian World Community and with the ideas upon

which this community is based.

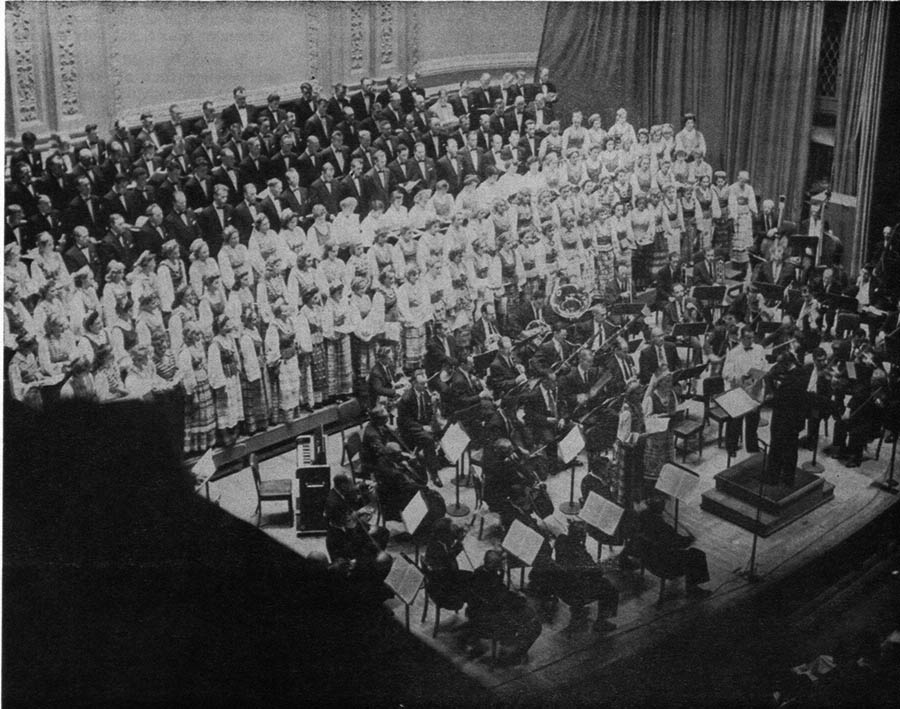

Concert at Carngie Hall

Photo V. Mazelis

What needs did originally evoke the idea of a World Lithuanian

Community? The old immigrants founded many organizations, particularly

in the United States, where Lithuanians are most numerous (up to

500,000 or more). The new immigrants, the former displaced persons,

also founded many organizations upon their arrival in the various

countries. And truly, there was no need for another organization, but

there was a need to combine all of the Lithuanians scattered throughout

numerous countries and numerous organizations into one. The need was

two-fold.

On the one hand, every organization not only unites but also separates.

A religious organization, obviously, cannot include atheists among its

members and inversely, Christians do not belong to a society of

freethinkers. And if in other cases the division is not as extreme, it

still exists. This differentiation leads to certain tensions which may

develop into real conflicts. It is natural, that free men differ in

their opinions. But from the national point of view there is a danger

that these differences will obscure the essential point: national ties.

Lithuanian unity is the central idea upon which the World Lithuanian

Community is based. In principle, this community unites all Lithuanians

without exception, for it excludes only those who have sold themselves

to the Soviet Union. These are a minority of the older immigrants who

have been deluded by Communism. Regardless of the individual's

religious, political or social views, the Lithuanian Community unites

all into one body, the heart of which is Lithuanian brotherhood and Lithuanian consciousness.

Lithuanian brotherhood bridges all differences, while Lithuanian

consciousness illuminates the fact that in any battle the essential tie

cannot be forgotten. The Lithuanian Community, in organized form

expresses the Lithuanian will to preserve their nationality according

to the slogan, "Lithuanians we were born, Lithuanians we must remain."

Secondly,

it is necessary that the natural feeling of brotherhood become a united

will to preserve it from degeneration into futile sentimentalism.

Individual organizations (religious, fraternal and others) can only

fulfill the limited functions for which they were founded. But they

cannot perform those functions which demand the joint effort of all.

Yet the refugees have the duty of preserving all the activities and

institutions of the free cultural life which in normal times are

fostered by the state. For the realization of these common aims the

Lithuanian refugees united into a World Lithuanian Community. The

genesis of the idea first occurred some ten years ago among displaced

persons living in Germany at that time. These people had abandoned

their native land, not of their own free will, but due to force. Some

had been deported by the Nazis for forced labor in Germany. Others fled

their homeland from the approaching Communist terror. Both groups

tragically experienced the loss of Lithuanian independence, when the

end of the war did not bring her freedom but a second occupation by

Communist forces. Whether Nazi deportees or Soviet refugees, both found

themselves sharing the common fate of a refugee. Having no other

alternative, they emigrated to various countries. Although grateful and

loyal to the new countries which accepted them, they, nevertheless,

remain a unique kind of newcomers — immigrants with the consciousness of political refugees.

The normal immigrants leave their homeland in search for a better

livelihood and more or less sever their ties with the native land. They

exchange homelands hoping for a better and happier environment. A

political refugee, on the contrary, does not seek a higher standard of

living but is primarily fighting his political fate. Not the search for

happiness, but rather loyalty to one's self is the main concern of such

a refugee.

For many of them personal welfare problems hardly

exist: during the ten years of immi-grational life a comfortable

standard of living has been achieved. Usually newcomers would be quite

satisfied with this achievement, but a comfortable standard of living

is not sufficient for political immigrants. Personal welfare cannot

supplant the feeling of tragedy in face of the threatened destruction

of one's nation. Nations are mortal. In this age it is not difficult to

annihilate a nation of about three millions. Genocide is being carried

out in Lithuania while the world is silent and refuses to see what it

does not want to see. No Lithuanian, faced with this tragic

possibility, can remain satisfied only with personal well-being and

enjoy his personal happiness. The question does not concern only the

restoration of a Lithuanian state, but it Involves the life or death of

the whole Lithuanian nation. In view of this, every Lithuanian exerts

the will to remain within his own nationality regardless of the country

assigned to him by fate. The World Lithuanian Community is the best

means of expressing the will of Lithuanians in the free world to remain within the nationality, to preserve the ties and to remain Lithuanian wherever they may be.

But

how can this will be realized In the "melting pot" reality which Is the

lot of all immigrants? How can the loyalty to one's native land be

reconciled with loyalty to the new country? The problem can be solved

without recourse to the "melting pot." And although the "melting pot"

is the usual fate of the immigrant, It Is an essentially futile

solution. Futile from two points of view: that of the immigrant himself

and that of this new country. For denationalization always implies

de-spiritualization; all interests are reduced to the primitive drive

for personal happiness; in fact this is equivalent to the stifling of

all the profounder interests, for it involves abandoning all roots in

the spiritual reality which is the respective national tradition. And

in this manner, the country which gains this individual gains nothing

more than mere "labor force." This "labor force" can be desirable and

valuable as "raw material." Its social integration, however, always

gives rise to problems. (It is not surprising that the question of

personal and social adjustment, as well as juvenile delinquency,

experiences its greatest intensity in the United States, which has

frequently been identified with the "melting pot" approach).

The

World Lithuanian Community is the expression of the Lithuanian

determination to become acclimated not through passive submission, but

through positive contribution of their culture to the country which has

become their new homeland. This is determination to become integrated

not through the loss of self, but through the preservation of one's

self, and at the same time through the contribution of all that is

valuable in the national tradition. This is the more difficult road,

but it is certainly more fruitful. From the personal point of view, an

individual, determined to follow this road, also chooses to face the

tension between two cultures. In certain cases this cultural tension

may give rise to problems of adequate adjustment. At the same time,

however, this determination enables the individual to integrate himself

freely and creatively within the new country rather than blindly

submerge in the "melting pot." All countries are worthy of respect and

patriotic love. But love, which remains blind, is of little value. True

love is never satisfied with that which is, for it is always

accompanied by the search for new roads and the imperative of

profounder ideals. All countries are worthy of being valued, but no

country is the "Kingdom of God," the final perfection. And, therefore,

those who can enrich the cultures of their new countries by means of

their particular national heritage are always of greater value than

those who lose themselves and feel that the adoption was successful,

while in reality it only added to the masses which are equally

international in their primitive-ness. Freedom not to think, "peace of

mind," Coca-Cola, portable radios, television crime stories and

tasteless advertisements is not what America stands for; it means

freedom of thought, the pioneering spirit, Emerson and James, Th. Wolfe

and E. Hemingway, E. O'Neill and W. Faulkner. The same analogy is

applicable to any other country. The acquisition of new customs and

learning new language do not constitute complete integration. The loss

of one's self is not necessary in this process. Everywhere it is

possible to remain oneself and everywhere this is necessary in order

that one's individuality could enrich others. In founding the World

Lithuanian Community, the Lithuanians of the free world have determined

not to succumb to the "melting pot," but to remain what they are and at

the same time make their own valuable contribution.

J. Girnius