Editor of this issue: A. Mickevičius

|

www.lituanus.org |

|

Copyright © 1963 Lithuanian

Students Association, Inc.

Vol. 9, No.1 - 1963

Editor of this issue: A. Mickevičius |

|

The Humanistic Expressionism of Vytautas Ignas

Stasys GOŠTAUTAS

Lithuanian art is more inclined toward the use of color, the portrayal of nature's beauty and the joys of life than toward the expressionistic depiction of social and humanistic problems. Bonnard, Vlaminck, or Redon's poetry of nature and symbolism lie closer to the heart of the Lithuanian artist than the anguished humanity of Beckmann, Rouault or Karel Appel.

That is why one rarely encounters man and his problems in the paintings of Lithuanian artists. Usually man is merely one of many other motifs, and it is only in the graphic arts that his influence is strong and dominating. Perhaps this explains why graphic arts dominate Lithuanian art and why the best Lithuanian painters are even better masters of the graphic medium: Jonynas, Petravičius (oils and graphics); Augius, Ratas, Valius, Viesulas (graphics).

It must be noted that Expressionism is not necessarily bound solely to the theme of man, but nevertheless man is one of the most important motifs and his emotions have been the main motivating force within this movement since the days of Grunewald.

In Lithuanian oil painting, the tragedy of existence plays a very minor thematic role or even no role at all. The so-called Lithuanian expressionists lack the German or American expressionistic dynamism, sensitivity, or vitality. They seek to say something about the man; hence, he often becomes merely a literary figure. Rather than expressing or revealing himself, man relates a narrative, and becomes a portrait.

Contemporary art requires investigation; inspiration and talent are not enough. A deep scientific investigation, as understood by Klee, Arp, Pollock and Tamayo, is also necessary.

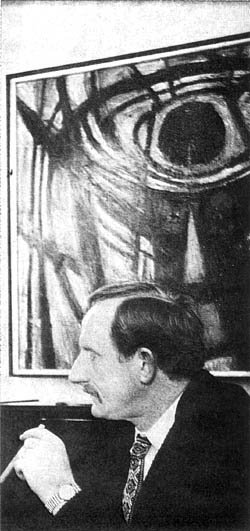

Among the Lithuanians, Vytautas Ignas may very well be one of the most interesting investigators. Although he is not yet the strongest of Lithuanian artists, Ignas is bent on the expression and clarification of philosophical problems through art, and is intuitively drawn to the unknown.

Ignas is a representative of the Freiburg generation, an artist of the post-war school, who grew up in the midst of the turmoil and upheaval of war, of the stress and strain of emigration and acculturation, experiencing their specific psychological significance.

Born in 1924, he finished his secondary school education in Vilnius, Lithuania. During the war, in 1941, he entered the Vilnius Academy of Art. After the war he was graduated from the School for Applied Arts in Freiburg, which had been established by the common effort of the French and the Lithuanians and trained a considerable number of Lithuanian artists, representing an entire decade of Lithuanian post-war art.

Upon arrival in the United States, Ignas worked in stained-glass studios in Chicago and Cleveland. He now resides in New York and continues his work in that medium.

Undoubtedly, the spirit of stained-glass work has considerably influenced his oils and graphics; this influence, however, is only accidental and affects form and composition, but not color, and has little to do with his ambitions and goals in the realm of painting.

Slowly, with great deliberation and exceeding diligence, Ignas strives to find his place in the world of Expressionism, whose human emotions deeply attract him. But his expressionism is inhibited and his emotions are constricted by timidity. Unsure of himself, he paints with minute, carefully thought-out strokes, so unlike the other violent expressionists and so much like a social scientist or a philosopher.

Just as many contemporary painters and artists, Ignas admires primitive Expressionism, finding it among the Mexican Indians and their descendants. This allies him with the social art of Mexico as interpreted by Rivera and Orozco. Yet Ignas' interest in this art is limited to form and does not extend to content. He does not seek to satirize, to criticize, to reform or even to pity the humanity he paints. He accepts it the way it is, as does Tamayo, who sharply differs from his fellow Mexican artists in his anti-polemic and anti-political position.

Ignas' paintings are very humane, full of a deep understanding for man, full of tenderness towards his brother, which explode suddenly in the violent darkness. It would seem that his subject matter is without color, yet at this same moment he sees the subject through color. This contradiction is more apparent than real, because Ignas does not try to depict objects, but only their emotion, his own emotion, which oppresses the canvas and often does not allow it to breathe.

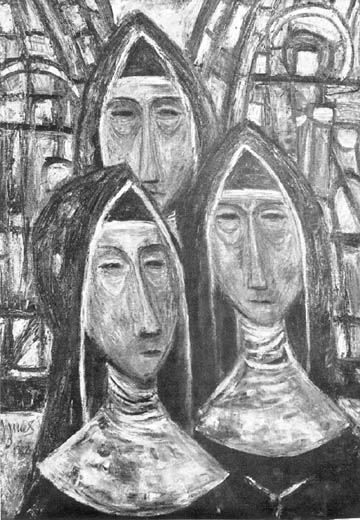

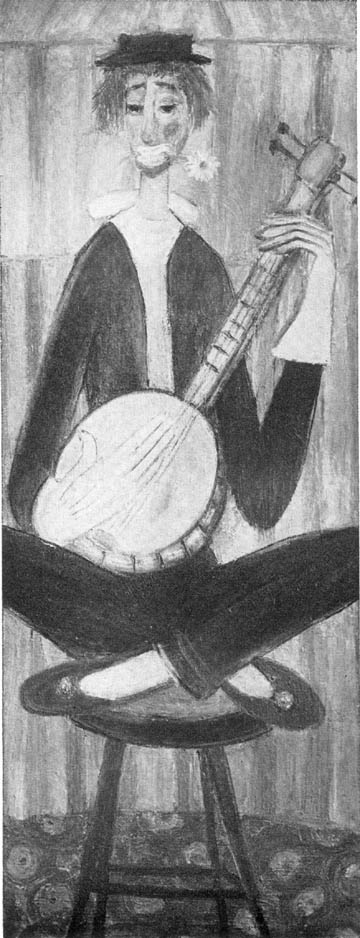

His work in the period between 1958 and 1961 is concerned with presenting his concept of man: "The Shoe Cleaner", "The Clown", "Girl of the Streets", "The Nuns in the Chapel", and so on. Without much artistic pretension they announce his further goals.

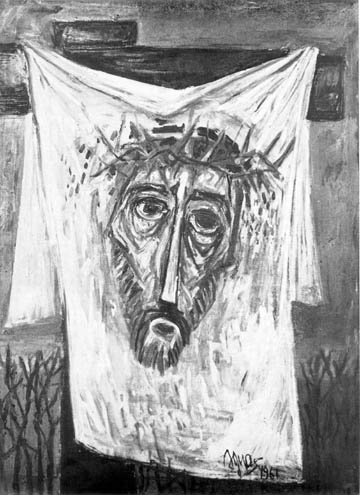

At the same time, Lithuanian folk art and primitive art in general presents him with a suggestive world of forms where he meets with "Rūpintojėlis" (the Lithuanian wayside cross), with the gods of the Indians, with the people. His hostile colors, his economy, his unlimited scatter and depressing gloom threaten to destroy that primitive freshness, but also reveal the intensity of life which we all have to endure.

Both these bases bring him to the present period, stronger and more tender, in which his artistic problems are clarified. Lines, forms, and colors fuse into one dark blot, in which one can even find textural pleasure. This pleasure has nothing to do with non-formal strivings. Ignas controls his emotions and does not allow them to conquer man. Often his paintings exhibit a tired, haggard look, through which he despair-fully and sincerely seeks to portray the enduring expression of man's existence.

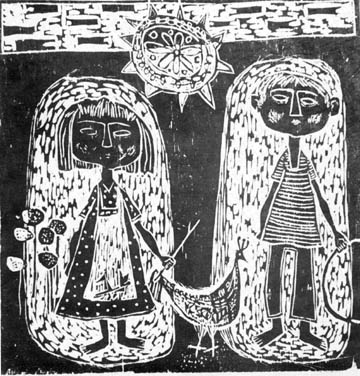

Exhausted by oils, he takes up water-color, allowing it to reveal his spontaneous feelings with a unique color range, free from concern with social problems. Water-color, however, does not leave a lasting imprint on his work. Much more important is his graphic work, in which the influence of the stained-glass technique, of religious folk-art motifs, and of the decorative elements of folklore is more pronounced than in the other artistic media he has employed. The heavy, complicated line drawn to excess does not leave enough room to breathe. Ignas likes to fill space completely, to tell all, leaving nothing to the fantasy of the spectator.

A final, conclusive statement about his work is not possible today; Ignas is well on his way, but he has not yet arrived at his destination. Along with many contemporary artists, he possesses the ability to create new forms and is always capable of surprising his observers. His continuous communication with man endows him with the outstanding ability to depict man's philosophical musings.

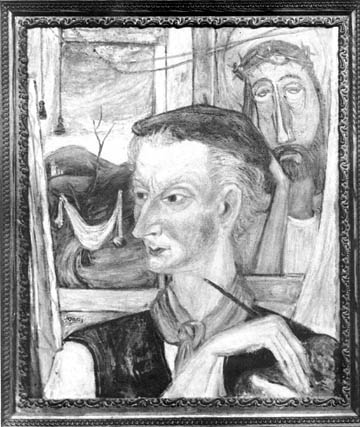

Self Portrait • Oil, 1958

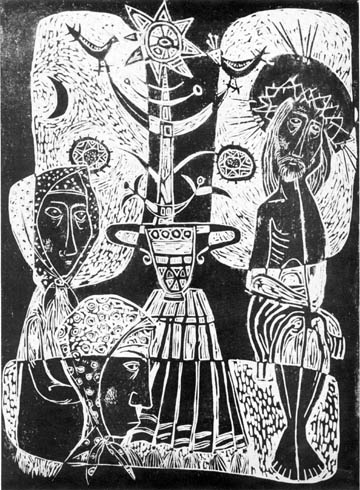

THE YOUNG SHEPHERDS • Wood-cut, 1962

WOMAN IN THE HAMMOCK • Oil, 1962

Veronika's veil Oil • 1962

THE OLD SAMOGITIAN CHAPEL • Lino-cut, 1962

FISHERMEN Oil • 1962

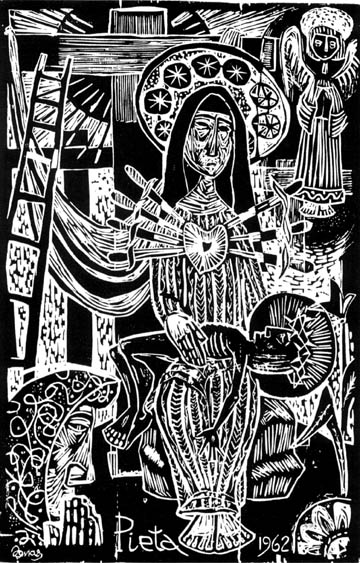

PIETA • Wood-cut, 1962

NUNS IN THE CHAPEL • Oil, 1962

CLOWN • Oil, 1956

SHEPHERD • Oil, 1959

THE CROSS • Oil, 1959

THE GIRL IN THE DARK • Oil 1961

THREE KINGS • Oil, 1959