Editor of this issue: Thomas Remeikis

|

www.lituanus.org |

|

Copyright © 1963 Lithuanian

Students Association, Inc.

Vol. 9, No.3 - 1963

Editor of this issue: Thomas Remeikis |

|

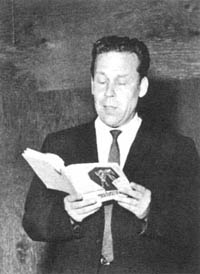

INTRODUCING THE POETRY OF HENRIKAS NAGYS

DR. JULIUS KAUPAS

Henrikas Nagys was born in 1920 in Mažeikiai, Lithuania. In 1940 he began to study architecture, but soon (1941-1943) switched to the study of Lithuanian and German at the University of Vytautas the Great in Kaunas. During the period 1945-1949, with a year's leave in Freiburg, he continued his studies at the Innsbruck University of Austria, majoring in German literature and history of art; here he received a doctorate for a study of the poetry of Georg Traki. Henrikas Nagys taught German language at the Applied Art Institute in Freiburg Br. (1947-1949) and literature at the University of Montreal, where he remains on the faculty to this day.

The first poems of Henrikas Nagys appeared in Lithuanian press in 1938 and 1939; since then he has made a notable contribution to Lithuanian poetry. He has published four collections of poetry — POEMS (1946), NOVEMBER NIGHTS (1947), SUN DIALS (1952), THE BLUE SNOW (1959); contributed to numerous anthologies and year-books of Lithuanian literature; has translated into Lithuanian from German literature (F. Hoelederlin, R. M. Rilke, F. Kafka and others), from American literature (C. Sandburg, T. Wilder), and from Latvian literature. In addition, Henrikas Nagys is a well-known critic and publicist of Lithuanian literature, a contributor to numerous newspapers and periodicals.

Henrikas Nagys belongs to the so-called ŽEMĖ (Earth) movement in Lithuanian literature; he was one of the initiators and editors of Literatūros Lankai, a modern review of the literary scene, closely connected with the ŽEMĖ movement. Being unsatisfied with erotic, patriotic, and religious themes, Nagys turned to the totality of human existence and extolled man's freedom for self-determination and his indeterminateness. Henrikas Nagys was readily accepted by the youth and was influential among the younger generation of poets. During the formative period of 1938-1946, one finds in Nagys' poetry almost all developments of the modern Lithuanian poetry. Nagys matured poetically in the poetic tradition of Western Europe; R. Dehmel, F. Nietzsche, R. M. Rilke and G. Byron were especially influential in his work. The poetry of Nagys is individualistic, idealistic and ideological. The principal ideas raised in Nagys' poetry are: the human struggle with the gray every day existence, the difficult human loneliness, the tragedy of death and transitoriness, promethean protest, the heroic spirit, the quest for an illusory ideal, and the torturous longing for perfect love. With powerful symbols and poetic parabolas Nagys writes about the insufficiency of earthly reality and the gnawing thirst for a more perfect reality. Nagys sharply depicts human conflicts without trying to provide a final philosophical solution to them. Often his poetry has a gloomy sense. Nagys, however, refuses to view human problems pessimistically and encounters them with a resisting spirit and a belief in the potential greatness of man. His poetry is youthful and committed. He attempts to change the world, to address man; he connects poetry intimately with ideological decisions.

Formally, Nagys rejects the traditional poetic schemes and instead uses free rhythm, numerous assonances, and free flow. Its features are suggestiveness, power, clarity of symbols, and its universal meaning. Nagys is one of the creators of the modern vocabulary of Lithuanian poetry.

Translated by Aldona and Robert Page

TERRA INCOGNITA

In the land of blue snow there are no trees:

only the shadows of trees and the names of trees

written by a somber hermit in the writing of the blind.

In the hall of mirrors not a single person is left:

only profiles cut out by the cutter of Tilsit fair,

and silhouettes traced on the dusty glass by the fingers

of the dead violinist late in the evening of All Souls.

In the valley of the ebbing rivers there is no birthplace:

only long rows of barracks, wooden sphinxes

with their sooty heads on their paws, dreaming

of flags, summer, sun and sand.

In the land of blue snow only names remain,

lines and drawings and letters remain on ashes.

In the land of blue snow there is no land.

PRODIGAL SONS

Late in the evening we came to the city gates.

Watchmen held out flaming torches to see our faces.

We listened in silence to their painful curses,

our hearts throbbing, our tatters soaked with autumn rain.

Come in, you tramps! they shouted at us. We went in,

into the town of our birth, having carried it long

in our hearts. Kneeling, we kissed the stones of the streets

and became drunk with abundance of words remembered

from lullabies. We thirstily drank from the passing lips.

Children with wide wondering eyes stood in the streets.

Until midnight... ah, it's just the night rain and icy chiming

of tower clocks that drips into my heart... Golden Honey

of my homeland! you enter through lips and hungry eyes...

How good it is to cry the tears of native clouds.

How good it is to sleep in the pavement of my birthplace.

Someone passes by us laughing. He blows out the lights.

A pale street walker collapses beside us sighing.

We rise. We are trees — silent and dumb. Our wooden shoes

echo on dark street corners like dry coughs.

The wind sways our rain-soaked, empty arms.

The muffled thunder of the foaming sea drums from afar...

Later we scooped up salty water with sweaty helmets.

And in the sea sand — as in a grave — we slept

under overturned boats

with stray dogs and the crumbled galaxies of yellow amber.

And with withered gray hands, we clutched them to our bare breasts

tattooed with pierced hearts and sailing ships...

And did not awake in the morning, not ever again awake

in the moving sand of the sea town of our birth.

From

FRAGMENTS OF CHILDHOOD

Strings of lifeless locomotives. Rusty rails in the fog.

In the work yard tar-spattered dandelions sway in the wind.

Small dirty hands gather them and take them home.

Behind smoky basement windows an old woman smiles in her sleep.

Weeping women carry baskets of bleeding fruit

and cringe when the trains scream. Crowds of poplars

have gathered in the gully to bury the dead sun.

I listen to their dirge while awaiting father's return:

His red lantern swings far off in the night.

Heavy familiar steps! With a coarse sweaty hand

he strokes my hair... Beyond the river soldiers sing...

In the flaming doorway mother waits for us.

Quietly crackling, the night burns in the hearth.

TO MY BROTHER

Tonight I can feel — he leaves his house:

—the autumn rainstorm beats against the panes —

he staggers in the streets, covering his face with his arms

as he weeps. I know. And I say to him:

When I write about trees that threaten the sky,

about a prophet whom the crowd has spurned, —

I speak to you, for you are my truest brother,

I speak to you so that you will not stumble

on the wet stones, so you will raise your sad head,

because you must live, my brother — you!

And you know: when in the attic of a dark house

at midnight — like a huge wound on the night

—

a window blazes — there has come,

to one man, your brother — the same suffering

which torments you at night like a black dream,

scorches you, but for which you cannot find the words;

and he, he searches for them on this night,

among these sighs of silence and in the tumult

of the storm's lament, in the sobbing of rain and branches;

and you would want to caress this man's

tired hands: he writes your words.

I speak to you. My silent brother.

When you are weeping I weep with you.

When I say: I am like a tree — solitary, proud —

then you can say: I am lonely and proud like my brother.

FIVE UNWRITTEN LETTERS

First letter:

ADELAIDE

You have come alone. The thick fog of Adelaide Harbor

smells of tar and poppies. The peculiar yellow sun

of an unfamiliar spring burns: an orange ball

bobbing in a wide muddy pool of sky.

You waded ashore, dreaming of black harbor waters,

like Gulliver towing after you l

little crystal boats. Over the slow flowing Torrens

the vibrating line of a bridge is piercing the night.

In the old German town (remember?) those plane trees entrusted

to you now rustle by another bridge over a shallow river:

in the morning children catch silver trout in their hands,

leaves whisper on the shore, winds play in the square.

The cathedral clock chimes the hour of ruins.

White moonlight crumbles. In the shadow of heavy counterforce,

where an Angel blows the trumpet of Judgment,

our footsteps stayed and echo. In Adelaide, you

dream in wintertime of a light bark boat in the snow.

In the jabber of parrots you search for a lost gray bird.

Bridges. The brick gate is red. The sun revolves

as an orange sphere in your dream. In Adelaide.

Second letter:

HONG KONG

The newborn moon blooms in the cherry orchard.

In Hong Kong.

Yellow and round, like a copper plate.

Like a gong.

My little sister with almond eyes, porcelain fingers,

watches how silk weavers indifferently die

on the fragile bridge railings in Hong Kong.

Rye whiskey is sweet. Shadows on thin silk

waver like hollow reeds in a faint aquarelle.

The bread of famine sticks in the throat.

Shadows wander from gray suburbs

through the marijuana smoke of the cafe like puppets.

And the moon blooms yellow in the desert. In the harbor.

In Hong Kong.

Gleaming and round, like a copper plate.

Like a gong.

My sister forgot a thousand years ago

that she knows how to laugh and cry. On the pond's surface

under the fragile bridge railings in Hong Kong,

Gioconda looks up at me with almond eyes.

Third letter:

GOLD COAST

Efua,

lakes of white moon milk ripple

in your dream. Supple

is your black skin, like the sacred

Modder Forest in the evening. Efua, your young

heart is like the thumping of your bare and drunken

feet, the drums' tom-tom and the rhythmical harvest song.

Efua, in your dream the orange sun has ripened,

naked bride of the morning and stone of innocence.

The wrists of your hands are light, like the hollow

bones of birds. Like a reed in the wind — your waist.

The golden hair of corn sighs in your dream.

A river of copper water boils. The palm tree's hands

beat the lazy wind in the shadow. You hold

your bow and arrow raised high. Efua, your winding path

is followed by the cunning eye of the tiger. But you

will overcome the beast and the dark foliage, where

the odd dreams of monkeys dangle and the wind's cool knives hang

after slicing a soft cloud. Warm lakes

of moon milk are steaming in your dream.

Efua, in your long, long dream.

Fourth letter:

BUDAPEST BALLAD

Imre, was it you who stood

(bareheaded in a student's woolen coat with child's eyes)

on the steps of a poet's monument that extraordinary October evening

and shouted into the dead silence above the endless sea of heads,

hoarse from your country's deserts and the tepid Danube wind

and the beating of your young blood:

"Arise Hungarians, your fatherland calls you!

The time has come! Now or never!

In the name of the God of all Hungarians, we swear, we swear

never again to be slaves!"

Was it you, Imre, that then repeated with the throng

and the earth, and the wind, and the water, this bitter oath of

freedom?

Imre, was it you who wrote

(in blood — what pathos! — in your young, warm

blood)

with bullet-pierced hand numbed by the first autumn frost,

in straight and red letters on the white bricks of the pier, s

o all could see: the snoopers, cowards, cohorts, and enemies,

in tall letters, the clotted scream: Death to the oppressors!

My land shall live forever!

Imre, was it you who covered

with your coarse woolen coat (and the flag, from which your friend's

hand had cut out — like an abscess — the shameful

star of slavery)

the haggard, gaunt body, your sister's loose yellow hair,

and laid words on the street pavement, torn up

by tank treads:

Sleep peacefully, little girl of Budapest,

your death was not in vain...

Imre, is it you who have written

on a narrow paper ribbon

those unforgettable sentences to us

from that night beyond, from that town convulsed in death

(while despair's black cannonade thunders... the Danube glitters

under empty bridges ... and bayonets ... narrow Mongolian eyes ...

the barbarian is at the city gates...),

Imre, did you write to us

from that last, terrible, immortal night:

"God, save Hungary.

God, save our souls.

Farewell, companions ..."?

Fifth letter:

LOS ANGELES

On the ocean shore barefoot angels are dancing.

Brass throats of trumpets scream blue sorrow.

Drunken poets recite in cafes — sharp shadows

of legendary birds slash with thin wings

the raucous curtain of smoke — through it

girls with loose hair covering their faces look out

at the quiet, apathetic, flat, mirror-like sea...

On hot asphalt barefoot angels are dancing.

Jungle drums throb the rhythm of wild blood.

Black poets sing midday, blazing day:

from ashen palm trees flocks of birds spill

over the dancing, screaming, raving city...

The eye of the burnt out sun smolders in the carnival flag.

On the harbor pier barefoot angels are dancing.

In cafes and taverns barefoot angels are dancing.

Black angels. White angels. Blue angels.

The poets have resurrected from the smoke a green coral island

and the homeland of the albatross. Brass jazz trumpets

tear at palm tree branches and crack the stone of skyscrapers.

Stained glass windows crumble and shop windows split.

Artificial moons flee through starless space.

On stars and broken glass barefoot angels are dancing.