Editor of this issue: Thomas Remeikis

Copyright © 1964 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 10, No.1 - Spring 1964

Editor of this issue: Thomas Remeikis ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1964 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

ALEKSAS VAŠKELIS

THE LIFE AND AGE OF KRISTIJONAS DONELAITIS

|

|

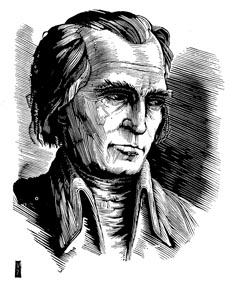

Kristijonas

Donelaitis

V.

Jurkūnas

|

In Prussian history the eighteenth

century is known as a period of

economic prosperity; in Lithuanian literature, it is known as the age

of Kristijonas Donelaitis.

At that time Lithuanian literature was making its first appearance and

was primarily aimed at filling the practical pastoral need of the

church. Set against the literary attempts of that period, the writings

of Donelaitis are of a high literary quality and originality. Not as^

piring to the level of literary art and rather intended to be didactic

moralizing, the work of Donelaitis, through its realistic portrayal of

rustic existence and masterful use of languoge, transformed the

practical ecclesiastical outlook of Lithuanian literature into one

reaching for originality and esthetic worth. More than any other among

his contemporaries, Donelaitis absorbed the economic, cultural, and

religious life of eighteenth century Lithuania Minor and expressed the

pulse of this life through a powerful suggestivity of language and

imagery.

The Eighteenth-Century World of the Poet

The country in which Kristijonas Donelaitis was born is known in Lithuanian as Mažoji Lietuva, i.e. Lithuania Minor; in German — Ostpreussen, i.e. East Prussia. The name "Prussians" refers to the Western branch of the Baltic peoples, who since prehistoric times have inhabited the area between the lower Vistula river, the Baltic Sea, and the Nemunas (Memel) river.1 Thus, the original Prussians, as relatives of the Lithuanians and Latvians, must be distinguished ethnically and historically from the Germanic Prussians, the descendants of the Teutonic Knights, conquerors of the autochtonic inhabitants of East Prussia.

In the thirteenth century the Prussians were conquered by the expansionist order of Teutonic Knights. After the suppression of the great Prussian revolt (1260-1274) against the Teutonic Knights, the Prussian lands were systematically colonized and germanized. By the eighteenth century the original Prussians were extinct. Nevertheless, East Prussian territory was still heavily populated with Lithuanians, and the Lithuanian language was dominant in many districts East of Koenigsberg, especially along the line of Gumbinen-Tilsit.2 Both historically and ethnically, therefore, the designation of Lithuania Minor is appropriate for this region.

In 1525 the Teutonic Knights became Lutheran and established secular Prussian state, including the conquered original Prussian territories, with the first lay ruler Duke Albrech von Hohenzollern at the helm. In 1618, as a result of a dynastic marriage, the Prussian state became part of the Duchy of Brandenburg. After the coronation of Fredrich I (1701), the entire Duchy of Brandenburg was named the Kingdom of Prussia. It is one of the ironies of history that the conquerors (Teutonic Knights) accepted the name of the conquered (Baltic Prussians).

The new Kingdom of Prussia sought to create an individual character, different from the other Germanic princedoms. Thus, it was desirable to call the kingdom Prussia and not Brandenburg and to show interest in the history of the autochtons of East Prussia, i.e. the Baltic tribes of Prussians and Lithuanians. To emphasize this uniqueness of the kingdom, Friedrich I was crowned not in Berlin but in Koenigsberg, the capital of East Prussia. Ethnographic, archeological, and historical materials on East Prussia were collected and published as a result of this heightened interest in the Prussian past.

Since the original Prussians were extinct (it is said that the last person speaking the Prussian dialect died in 1677), attention turned to the Lithuanians, the closest living relatives of the Prussians. Lithuanian history, ethnography, and language thus received the attention of the Prussian monarchy. This interest was evoked not just by the sentiments of German scientists, but also by the spreading Western tendencies of enlightment and by the new religious movement — pietism.

In 1709-1711, a famine and .a devastating pestilence struck East Prussia; about a third of the population was lost. The heaviest toll fell on the lower socio-economic classes, especially the Lithuanian serfs. In order to repopulate the East Prussian countryside, the Prussian authorities undertook ambitious colonization plans. The Prussian Minister of State Baron de Hertzberg gave the following figures on colonization : "I shall only say, in general, that the great Elector . . . also increased the number of his subjects, by providing asylum to 12,000 French refugees whom Louis XIV has driven from France on account of religion, and of which the number was afterwards augmented to 20,000. King Fredrich I received into his territories a considerable number of the subjects of the Palatinate, who had been driven from their country by religious persecution; and King Fredrich — William gave asylum to 12,000 Saltzburghers, who had been banished by a bigoted archbishop, and also to a great number of emigrants from the Palatinate and Moravia; and with these virtuous and industrious families, he repopulated the province of Prussian Lithuania, which had been entirely depopulated by the dreadful pestilence in the years 1709 and 1710."3 Gypsies, Poles, Jews, Samogitians (Lithuanians) were excluded from colonization of East Prussia by royal decree. Nevertheless, it is known that there were also colonists from Lithuania Proper.4 They were mostly former servants of free farmers who now wanted to become serfs. As a result of colonization, East Prussia became a truly multi-national area and the hereto dominant Lithuanian inhabitants often found themselves in a miority. In the years of Friedrich Wilhelm I there were only 172,000 Lithuanians in Lithuania Minor.5 Thus, when colonization was completed, there was approximately three Lithuanians for every one newcomer.

From the royal decrees it is evident that the local population was not overjoyed with the colonists. There were a number of complaints that the local inhabitants, besides hate and ostracism, had used even physical means of discouraging the colonists from settling in their neighborhoods. Such reaction by the local population may be explained by the favoritism and privileges that the colonists had obtained from the king, which resulted in better living conditions than those of the local Lithuanian serfs. At the same time, however, this social inequality and hate of one ethnic group for another excited the national sense and consciousness of the Lithuanians.

When the colonization subsided, the intermixing of ethnic groups had an acculturating effect on the local Lithuanian population as well as on the colonists. Althogh the process was slow, new ideas and customs brought in by the colonists, were markedly penetrating the conservative outlook of the Lithuanians and changing their way of life. Thus, in Donelaitis' poem we see how the way of life and the thinking of the Lithuanian serf was changing as a result of this colonization. Colonization of the country contributed greatly to economic reconstruction, but it also was fatal to the Lithuanian ethnic group. This was admitted even by German scientists who analyzed the process and consequences of colonization. The assimilation process was noticeable early in the use of language. L. Rhesa, the first publisher of Donelaitis' poetry, testified: "It cannot be negated that after the influx of German colonists into Prussian Lithuania, the language lost much of its former purity."6

The notable assimilation of the Lithuanians received attention and sympathy from German ethnographers and scientists, who sought to preserve disappearing cultural objects and ethnic, groups for posterity. Some of these people sincerely loved and aided their subjects of research (G. Ostermeyer, A. Schimmelpfennig, et. al.).

The Prussian government, however, influenced by the ideas of enlightment, was not concerned with this preservation of ethnographic objects. Its attention was focused on the practical education of the inhabitants, the reduction of illiteracy and the raising of the cultural level of society. Even the leaders in the Protestant Church (Lysius, for example) had suggested a germanization policy in the schools and in the church, despite the church policy of pastoral work in the language of its faithful. The germanization plan suggested by Lysius was not implemented because of opposition from a large number of Lithuanian pastors. It was only in 1739 that Wilhelm I gave the final order to start germanization of East Prussia. Such royal decrees, however, were unable to stop the Lithuanian national resurgence; the creative potential of the Lithuanian nation continued to be realized, despite the lack of government support. The leadership of the church could still give some support to religious writings and tolerate works of practical nature (grammars, dictionaries, philological studies), although the original literary works had to remain in manuscripts. (Schimmelpfennig, Do-nelaitis, Mielcke).7

Lithuanian Language and Literature in Lithuania Minor

|

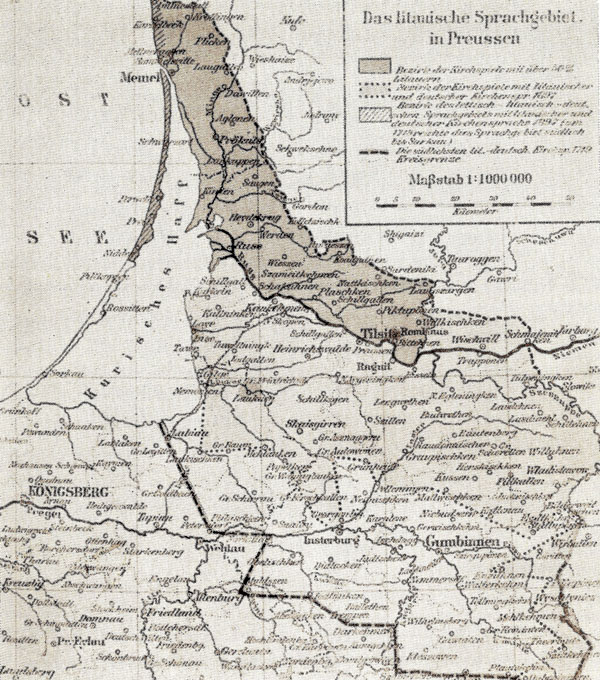

| Lithuanian Language Area in East Prussia, a map by Franz Tetzner (Die Slawen in Deutschland, Braunschweig, 1902) |

With the rising level of literacy in the eighteenth century, the need for religious literature in Lithuanian language was constantly increasing. The leadership of the German Protestant Church, still adhering to the principle that the Bible must be taught in the language of the faithful, participated quite actively in the preparation of religious literature in Lithuanian (J. J. Quandt, for example). The pietists, concerned with the popularization of their movement and in competition with the orthodox clergy, also were deeply involved in this activity. The long-advocated idea that in the preparation for pastoral work the candidate must be taught Lithuanian, was finally realized in 1723 with the establishment of a Lithuanian language seminar in the theological faculty of the University of Koenigsberg. A similar seminar for pietis-tic competion was also established in Halle University (Halle a.S.). Although these seminars did not realize their full potential, nevertheless their significance cannot be underestimated. Several textbooks on linguistics were provided for the needs of these seminars. In the seminars, pastors of German origin learned the fundamentals of Lithuanian language; later, working in Lithuanian parishes, they learned the language well and actively participated in preparation and publication of religious literature in Lithuanian. K. Donelaitis also attended the seminar at Koenigsberg Univeristy, directed by F. Schultz, and became acquainted with the theoretic fundamentals of his native tongue.

The pastoral needs of the church called out a flurry of activity, directed at providing religious literature in Lithuanian. The Bible and the hymnals had to be translated and published, dictionaries had to be compiled for German pastors, fundamentals of grammar, syntax, and literary style had to be established. The eighteenth century was truly "a century of language."8 With the developed linguistic tools and poetic experience (in composing hymns, for example), it was not difficult to make the inevitable jump to a true secular literature and thus to the beginning of Lithuanian literature.

Within the limited space of an article it is only possible to provide the highlights of the intense activity in the development of the Lithuanian language and religious literature in the eighteenth-century Lithuania Minor.8a

One of the first to raise problems of Lithuanian language was M. Moerlin (1641-1708) ; in 1706 he published a booklet advocating linguistic reforms in religious literature, a cleansing of the language, closer usage of the folk idioms.9 On Moerlin's suggestion, J. Schultz issued the first Lithuanian translation of Aesop's Fables.10 This was the first secular literary endeavor in the Lithuanian language.

Among the publications raising linguistic problems were the translation of Luther's New Testament (1727)11 and the full translation of the Bible (1735).12 The translation of the Bible was a collective undertaking, involving a number of pastors who knew the Lithuanian language. Since various parts of the Bible were translated by different translators, the quality of translation varies. Nevertheless, it must be admitted that the language of translation and its artistic quality displayed progress. The Bible was very popular and a second edition with linguistic corrections was planned for 1755. This work was one of the greatest contributions to eighteenth-century Lithuanian literature, a guide to linguistic principles.

Religious hymns were one of the essential features in 'protestant services. The use of hymns was even more accented by the pietists, who emphasized the "emotional" aspect of religious services. Thus, the preparation of hymnals was also quite a pressing need; the Protestant clergy of Lithuania Minor devoted much attention and time to this end. The translation of the Bible raised linguistic problems; the translation or composition of original hymns raised new problems concerning the poetic techniques. Hymnals issued in the seventeenth century were still in use at the beginning of the eighteenth century. It soon became evident that the old hymnals lacked hymns expressing the new spirit and mood emphasized by pietism. Since the church was concerned that hymns of proper content be used in Lithuanian churches, it took initiative to get a collective working on a new approved hymnal. As a result, a large hymnal, edited by J. Behrendt appeared in 1732. Just as the translation of the Bible, this hymnal became a standard book of eighteenth century Lithuanian literature; it was published in about ten editions with continuous changes and supplements.

Some of the most significant early works on Lithuanian language were done by Phil. Ruhig (1675-1749). The most important of these works is his Betrachtung der Litauischen Sprache in ihren Ursprung, Wesen und Eigenschajten (Koenigsberg, 1745). Using the phonetic comparison method of words in different languages, Ruhig hoped to determine the degree of relationship between Lithuanian and other languages. In general, he writes extensively on the worthiness of the Lithuanian language, focusing on its uniqueness and its richness of expression. To illustrate his contentions, he included three folk songs and a considerable number of proverbs, sayings, and idiomatic expressions. Ruhig's conclusions lacked' scientific basis, but they suggestively affected literary workers. Several of them even became proud to be able to speak one of the oldest European languages. This also contributed to the development of Lithuanian national ambitions and to the emergence of national pride.

After Ruhig's publication of examples of folklore, a heightened interest in Lithuanian folklore became evident. This interest, of course, was related to the rising new literary mood in Western Europe, whose initiator and theoretician was J. Herder. As a result of Herder's campaign, interest in folklore reached new heights and folklore itself was beginning to be considered as part of literary creativity.

Under the influence of the beginning romantic movement, a literary group in Koenigsberg interested itself in Lithuanian folklore. J. A. Kreutzfeld (1745-1784), a teacher in one of the schools of Koenigsberg and later a university professor, was one of the most ardent collectors of Lithuanian folklore. He seems to have spoken Lithuanian, for he provided translations of Lithuanian folk songs to the contemporary periodical press of East Prussia. He also has written several articles, analyzing the poetic techniques and melodic characteristics of the daina. j. A. Kreutzfeld was in close contact with Herder. Most of the Lithuanian folk songs in Herder's collection Stimmen der Voelker in Lieder were provided and translated by Kruetzfeld.

In the eighteenth-century Lithuanian cultural life, folklore did not yet gain a strong recognition; it was still too early. Under pietist influence, the Lithuanian clergy viewed folk songs and folklore in general as a subject unfit for interest and contrary to their entire conception of pastoral duties. Nevertheless, the pervading mood of the epoch penetrated the literary orbit of Lithuanian life and the influence of the times was felt even in religious Lithuanian literature, i.e. in the religious hymns.

It is quite difficult to determine in the literature of the eighteenth century where the religious literature ends and secular literature begins. In the content of religious hymns we sometimes note a straying from purely religious motifs. Such hymns are often emotional or even lyrical expressions and it is a short step from here to secular poetry.

The more likely beginning for secular poetry, however, will be found in the contemporary tradition of writing rhymed verses in newspapers or in letters of greetings or condolence. This practice was quite popular in East Prussia and was adopted by Lithuanian writers. One uf the most outstanding practitioners of the art of "occasional" poetry was A. Schimmelpfennig (1699-1763), who was also a successful composer of religious hymns and an editor of hymnal's. His secular poetry is far from esthetic heights, but in its treatment of themes and in the accompanying moods it had a significant influence on the literary development of the period. In the declaration of national pride, in the defense and advancement of Lithuanian interest, Schimmelpfennig's work had an undeniable influence on Donelaitis and on his national commitment. His rhymed introduction to the revised edition of the Bible and his rhymed letter about student life in Koenigsberg were entirely new manifestations in the religious Lithuanian literature and may be considered the early examples of Lithuanian belles lettres.14 Schimmelpfennig's colleagues Donelaitis and Mielcke, taking the same road, led Lithuanian literature to esthetic heights.

The Life of a Poet

Knstijonas Donelaitis15 was born on January 1, 1714, in the village of Lazdyneliai, parish of Gumbinen, East Prussia.16 Lazdyneliai (Lazdinehlen in German) was a small village about 5 km. east from Gumbinen. Because of plague and of colonization, the nationality of the village had become mixed. When Donelaitis was born, the village consisted of Lithuanians and Germans in approximately equal proportion.

There are very few facts available about Donelaitis.' parents. Documents of the period indicate that his parents were free farmers, i.e. had a title to the land they cultivated, were free from feudal obligation, but had to pay certain taxes. At that time, such socio-economic status was considered to be somewhat superior to that of the serfs.

Members of the Donelaitis family were the original inhabitants of the area -— Lithuanians. There were people who tried to raise doubts about it. For example, the Donelaitian historian Franz Tetzner had suggested that Donelaitis possibly came from Scotland or England. He based this speculation on the names of traders who came into the country in the seventeenth century, such as Doneelson, etc.17 Tetzner's contentions lack serious basis; there is a general agreement on the Lithuanian ancestry of our poet. The first reviewer of the German translation of his major work The Seasons J. Penzel has declared Donelaitis to be "entirely Prussian (i.e. Balt)."18

Kristijonas was the youngest of the seven children in the Donelaitis family. It is said that the father, besides the ordinary work on his farm, tried his hand at making various mechanical things. This characteristic evidently was inherited by his children. The eldest sun Friedrich became a goldsmith and a noted maker of musical instruments in Koenigsberg. Michael took over farming, but also became a goldsmith and died in Tolminkiemis. as "em Juwelier seiner Kunst." The third son Adam became a blacksmith. Considering that Kristijonas himself made pianos, barometers, ground optical glass, fixed watches, etc., the tendency to mechanics of the Donelaitis family is quite evident.

In 1720, Donelaitis' father died and all upkeep and education of the family fell on the mother's shoulders. Most of the children went into the world and learned a trade. What happened to Kristijonas immediately after the father's death is not known. Twelve years later (1732), however, Kristijonas was attending a middle school of Kneiphof — a section of Koenigsberg founded by and named for the Magister of the Teutonic Knights W. von Kniprode. Until he entered the university, Kristijonas evidently lived in an orphanage. For his room and board he had to perform certain religious functions: sing in the cathedral choir, participate in burial services, etc. According to the testimony of his niece, Kristijonas' life in the middle school was hard and poor; once he even fainted from hunger. Nevertheless, as his record testifies, he was devoted to his studies. Besides Lithuanian and German, two languages that he knew from childhood, he learned Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and French. Kristijonas finished the middle school at the age of 22 and entered the University of Koenigsberg in 1736 as a Lutheran thelogy student.

Very little is known from direct sources about Donelaitis' student days. Indirectly, however, his academic and social environment can be reconstructed quite accurately.19 From this it is possible to deduce quite plausible conclusions of the molding influences of Donelaitis.

It is difficult to say why Donelaitis chose theology. The Faculty of Theology received government and church support and its students could hope to receive aid, an especially important condition for poor students. Lacking in means, Donelaitis could hardly consider some other subject of study. Those that graduated from the Faculty of Theology and were Lithuanians usually were appointed to teaching or to pastoral positions in Lithuanian parishes. K. Donelaitis grew up in Lithuanian surroundings and appears to have been of Lithuanian disposition — his national background, thus, could have influenced the choice of profession.

During the years of Donelaitis' studies (1736-1740), the University of Koenigsberg, under the influence of the spreading Western tendencies of enlightment, gradually was reorienting itself toward a new-direction and its scientific level was rising. Nevertheless, the old scholastic tradition was still dominant — literature and oratory were still taught as one subject in the Faculty of Theology. Classical literature was the basis of literary studies, with special emphasis on Horatius De Arte Poetica. Poetry, a subject related to the wider literary life and esthetics, was taught in the Faculty of Philosophy. This subject was not required for theology students, but anyone could attend the lectures. J. Pietsch and J. Boch, professors of philosophy, were known writers of "occasional" poetry. J. Boch justified deviations from the norms of classical poetry; it is possible that Boch had some influence on Donelaitis, who also did not attempt to evade digressions from the requirements of classical verse. Some of the other professors that could have participated in the development of Donelaitis' poetic talents were: J. W. Quandt, a professor of theology, known as very articulate preacher, a participant in the organization of Lithuanian religious literature; G. Pisanski and D. Arnold — famous literary historians; F. Schultz — head of the Lithuanian language seminar.

The Lithuanian language seminar was mandatory to all theology students from Lithuanian - speaking areas of East Prussia and, therefore, to Donelaitis. It was traditional for a student with better knowledge of Lithuanian to direct the practical excercises of the seminar; it is likely that Donelaitis also had to perform in this capacity. In the seminar he was acquainted with the principles and rules of grammar of the Lithuanian language. Available facts, however, indicate that the level of the seminar was very elemental. Even Donelaitis himself later regretted: "I often wrote poorly orthographically in Lithuanian, for I was not concerned with the matter; nevertheless, I spoke well."20 Lithuanian was his native tongue and he probably had few problems with the spoken word, but grammar was another matter. The Lithuanian language seminar helped Donelaitis to acquire only the basic rules of grammar.

Music undoubtedly contributed to the formation of his esthetic views; music was a requirement for all students. Musical life in Koenigsberg during Donelaitis' studies was quite lively, the city and the faculty and students were interested and participated in musical activities. University musical circles performed publicly in the city and organized music festivals. It is quite possible that Donelaitis participated in this musical life, for he had a musical talent — he could play the piano and the harpsichord, wrote music for his poems, and made musical instruments.

In 1740 Donelaitis completed his university studies. His activities the next few years are quite well summarized in the following autobiographical note:

"In 1740 I moved to Stalupėnai as a Cantor. That was at the end of July. In 1742 I became a rector of the school and in 1747, before Whitsuntide, I received an offer from Tolminkiemis. Being concerned with students, I remained in Stalupėnai until the middle of summer. On July 24 I traveled to Koenigsberg. On October 17 I was examined, on 21st — ordained, and on November 24th (24th Sunday after Trinity) I was introduced to the parish of Tolminkiemis; I commenced my duties in the old church on the first Sunday of the Advent. On October 11, 1744, I married. I had no children, which was fortunate, for the service is of average desirability. My precentor at that time, whom I found, was called N. Sperber. We together attended the school in Kneiphof and roomed together in ... room C of the old dormitory of Albert's college. As impoverished students we ate in the diner of the dormitory. In 1738 he (Sperber) invited me to Tolminkiemis already as a pastor. We got along very well. In 1756 after Whitsuntide he left for Kuncai and from there one summer he visited me, already as a parson. He transferred from Kuncai to Gaivaiciai, where he died. He had been in Tolminkiemis somewhat longer and knew many things and I was not aware of".21

Donelaitis' life as teacher in Stalupėnai was uneventful. When the rector of the school died, Donelaitis took over. In 1744, in Tolminkiemis, Donelaitis married the widow of his predecessor. As a teacher, he seems to have been devoted to the students. At that time reading and analyzing of fables was a widely accepted pedagogic method, for the children easily understood such materials. It was probably here and with the pedagogic aim in mind that Donelaitis wrote the six known fables.

In 1722, when Donelaitis arrived to take over the parish of Tolminkiemis, the parish was ethnically mixed. Pestilence and famine had reduced the Lithuanians to a minority. Of the 3,000 inhabitants of the parish, only 1,000 were Lithuanians; the rest — Germans and colonists.22 Thus, on Sundays the pastor held morning services in German and afternoon services in Lithuanian. In Tolminkiemis, as in the rest of Prussia, feudal economic structure was very much in evidence. Within the parish borders there were four royal estates, one of which in Tolminkiemis itself, two free farmers, and 32 feudal villages.23 As the pastor of the parish, Donelaitis had charge of a farm that was approximately 37.5 hectares in size.24 As the spiritual leader of an ethnically heterogeneous feudal community, Donelaitis was forced to take an active part in the national and economic struggles of his people.

Donelaitis spent the rest of his life in Tolminkiemis. He performed his pastoral duties with great devotion and dedication. After a visit to Tolminkiemis in 1774, S. Mueller, a representative of the church, reported: "The local pastor Kristijonas Donelaitis is 61 years old and a pastor in this place for 32 years; gives sermons in German and Lithuanian, the latter with great competence."25

The available acts and documents testify that Donelaitis was a good parish administrator, an astute organizer of parish construction. He built a new church, renovated parish buildings, built a home for the widows of parish pastors at his own expense and donated il |o the parish, and rebuilt a burned-out school. From the existing records it is evident that at first he was enthusiastic about running the parish farm. He made detailed plans of fields and compiled instructions for his successor. He himself cleared fields of stones, dug ditches, planted trees. Donelaitis apparently did these things more from a sense of duty than from a genuine liking for the occupation. He often complained about this burden: "You, parsons in the cities, who do not have to be concerned with farming, how lucky you are".26

Besides construction and farming Donelaitis was quite successful in making various mechanical things. Donelaitis' contemporary, the Rev. Jordan, has left the following information on this point: "I became acquainted with him (Donelaitis) only in 1776, though I had heard about him so much earlier: about his mechanical and optical work, about the grinding of glass, barometers, one of which I had acquired and which was very good, about the excellent pianoforte and two pianos which he had made . . . about his musical compositions and similar things."27

The circle of Donelaitis' friends was small, but those that he associated with were true and noble friends. An especially close relationship developed between Donelaitis and the Rev. J. Kempfer and the Rev. j. Jordan of Valterkiemis parish. One of the remaining letters by Donelaitis to Jordan testifies of the nature of their relationship:

"It was a pleasant consolation, when my beloved, highly honored confrere from Valterkiemis (Kempfer), also my beloved, highly honored your father and you yourself visited my home last winter. I would like to entertain my old ears more often as then. As far as I still remember, the subject (of our discourse) was the world of all kinds of heroes: "The friendship of David and Jonathan," "The labors of the first people," "Fortune and misfortune, or concerns," and finally "Hope" and what is related to it, for hope is needed for all kinds of things, especially in misfortune and house-keeping activities. Finally we heard Krizas relating his adventures and how sorrowfully the good amtman was mourned."28

The mentioned works did not survive. They were Donelaitis' German works, for which he himself wrote musical accompaniment. Apparently the friendship of J. Jordan was pleasant and useful to Donelaitis. Although Jordan was younger by 39 years, the common interest in literary questions and esthetic problems in general tied the two men together fairly closely.

There is convincing evidence that Donelaitis was concerned with and involved in the preparation and publication of Lithuanian religious literature. He undoubtedly used this literature in his pastoral work with Lithuanians and commented on its merits or demerits. He was also known to the Lithuanian pastors as an artist and was invited to participate in the preparation of hymnals and other religious publications.29

During the Seven Years War, when the Russians invaded Prussia (1757), Donelaitis with most of his parishioners retreated to the forests of Rominta and there held services and performed other religious functions. This retreat lasted close to a month. Back in Tolminkiemis, in the parish records Donelaitis expressed joy at his return home and at the same time lamented the great harm brought to the country by the invasion.

With the end of the Seven Years' War (1763), life in Tolminkiemis took on a peaceful course again. The war affected Tolminkiemis very superficially and we find no reflection of it in Donelaitis' poetry. The period 1765-1775 is the most peaceful and creative period in Donelaitis' life. The writing of The Seasons, a poem on the life of the boors during the four seasons of the year, is definitely ascribable to this period.

In 1773-1774 Donelaitis reviewed the vital records of the parish, which were variously annotated; some of these were corrected, others deleted. At this time, between 1773 and 1779, he wrote a testament to his successor: "Allerley zuverlaesige Nachrichten fuer meinen Successor." In-,this, testament we find many autobiographical notes and reminiscences, as well as advice and instructions.

The peaceful and creative period in Donelaitis life ended in 1775, when the Amtman, i.e. administrator of the royal estate in Tolminkiemis, Ruhig, started the separation proceedings for the common pasture-lands of the royal estate and the village. Donelaitis was not against the idea of a just separation of royal estate and village pasturelands, but vigorously opposed Ruhig's attempts to appropriate the best land for the king at the expense of the parish and the village. He wrote letters to judicial organs in Gumbinen, and complained about the injustices of Amtman Ruhig to authorities in Koenigsberg and even in Berlin. He was especially outraged at the decision of the separation commission, which was bribed by Ruhig. Donelaitis refused to accept the decision and was taken to court as obstructionist to separation. He wrote to his successor: "I withstood pain with great patience, and where it was possible to get along without scandal and outrage, carefully and vigorously I fought for the church and its land".30 This conflict with the royal estate lasted for a long time and was resolved by a court in favor of the parish only five years after Donelaitis' death.

Age and the protracted conflict with Amtman Ruhig were making Donelaitis nervous and ill. From letters written in 1777, we know that he tried his hand at musical composition. He complained that shaking hands prevented him from making barometers. His handwriting in the parish records of that time is very difficult to read.31

Donelaitis died on February 18, 1780, at the age of 67. He was buried under the church of Tolminkiemis. His successor, the Rev. Wermcke, on assumption of pastoral duties, entered the following into the parish records: "Donelaitis, who served here 36 years, has left to his 'successor in all his parish records many good instructions. Did he not use this advice as a rule for his own life? I, his successor, had not known him. Though he was known as a great artist, which I found out early after his death, I know nothing else of his death."32

The Character of a Shepherd

Donelaitis, one of the greatest and most impressive representatives of Lithuanian literature who left such clear and actual description of the peasants of his time, left very few facts about himself — the man and the poet. His confreres and friends are also of little help in this respect. In describing the features of Donelaitis' personality, in recreating his human portrait, we have to rely on the direct sources left by Donelaitis himself: his inscriptions in parish records, his correspondence with governmental authorities, and, of course, his poetry, which is an irreplaceable source for determining his world-view and personality.

Having spent the years of education in indigence and hardship, he did not attempt to have a comfortable, and perhaps extravagant life even when he became pastor of the well-to-do parish of Tolminkiemis. Luxury and other pleasures of comfortable living were foreign to his pietist character. According to Schultz, "he was a man whose character was inconsistent with the spirit of this era."33. Schultz has described Donelaitis' in the parish deceased record as a "faithful admirer and lover of the true science of Christ."34 This characteristic indicates that Donelaitis was quite active in the pietist movement, for at that time pietism claimed to have been emancipated from hypocracy and dogmatism and to be the true Christian science and true life in the spirit of the science of Christ.

There is nothing to indicate direct relation between Donelaitis and the academic pietist movement. In reading his opinions, his and his colleagues' letters, however, we see that Donelaitis was a pietist in the full sense of the word. Donelaitis disliked entertainment, noise, could not stand smoking and drinking. He was serious, devoted to physical labor. He set a rigid pattern for his life and strictly adhered to it. This is very evident from his notes in the parish records, in which he was concerned not only with the negligence of his confraternity, but equally with hi.-; own weaknesses.

During the first years as pastor, Donelaitis displayed a very strict disposition concerning moral principles and was an uncompromising supporter of Lutheranism and a representative of pietistic devotion and pietistic asceticism in life. At the beginning of his pastorate Donelaitis was even intolerant of other religions. In the vital records of the parish we find a number of unfriendly references to the members of the Reformed Church. It is known that Donelaitis had insisted on re-baptizing children of the members of the Reformed Church, for which several complaints reached the government. As time went by, Donelaitis mellowed. In the baptismal records we find a note dated November 30, 1773, in which he admits that there are good men even among the members of the Reformed Church: "After 30 years, finally I found this out."35 In a way, this explains why we find obliterated notes in the parish records; Donelaitis changed his mind when he was 60 years old and thus retroactively struck out some of his opinions. In moral matters, however, he remained strict and uncompromising. Being honest and forthright, he liked to tell the truth to one's face; he scolded and taught his parishioners, not attempting to evade public condemnation and degradation. This is evident from complaints to the government and from Donelaitis' notes in the parish records. The following are some of his caustic remarks.

"May 28, 1775. Father — a soldier by the name of Joh. Xavier Seyffert, who before the wedding lived with a woman, and after this was not married for the lack of wedding certificate. The mother — a triple whore."36

"January 30. Father — George Bauman, a convert from the Reformed Church, servant, who had promised to marry, but disappeared when pregnancy was evident. Mother — Anne Catharine Marquart, daughter of the farmer Christup Marquart from the Didžiuliai village, a creature worthy of mercy. Daughter: Katarina — child of a prostitute."37

"N.B. The entire family from a pigs' sty. Mother has prostituted herself so that her body is rotting and already several years she is bedridden and dying in T. (locality)"38

He was no less critical of his confreres. Where the bitter truth had to be told, he did it without scruples and named the transgressor. For example, he had characterized the precentor of Tolminkiemis, the Rev. Tortilovius as "dark and devious" person; on another occasion, Torti-lovius was ridiculed for the Lithuanian sermon that he had preached.39

Moral weaknesses of his parishioners deeply affected Donelaitis' sensitive nature. Notes inscribed in the vital records were not just a simple registration of facts, but a genuine reflection of a sensitive soul. Entering into the baptismal records an illegitimate child Donelaitis was overwhelmed by depression and pessimism. He could not hide his wrath for the parents: "You "good" parents, you animals! Is it not your sin, that your shame must be born by your children ? But does anyone care?"40

On the basis of these subjective notes, dedicated to his successor, we cannot be of the opinion that Donelaitis woed sinners, promising them God's love and forgiveness for their sins. He was a pastor who scolded and threatened. It seemed to Donelaitis that a sinner is beyond redemption and there was no need to be concerned with him. The uncorrupted society needs only to isolate itself from such people. Only people of primitive spiritual construction are true and good sheep of the church. Donelaitis thought that one must be on guard to see that bourgeois behavior does not affect such uncorrupted society, that alien influences do not affect its members, shatter their conservative shell and deform their naive and natural spiritual make-up. This viewpoint is at the basis of Donelaitis' admiration for the Lithuanian peasant, whom foreign colonists wished to induce to follow more modern and newer ways. Donelaitis stood staunchly against this modern progress. The leitmotiv of Donelaitis' poetry is the defense of old traditions, the rural man, conservative in his views.

Donelaitis tried to perform all duties required of him with pietis-tic dedication, though not all the duties were equally pleasant to him. Apparently, he liked teaching; he was devoted to students and concerned with their welfare. In the Tolminkiemis parish he was in charge of five parish schools and devoted much attention to their operation. He had even made plans and maps of the most expeditious ways the children can ,reach the school. Then also moralizing, didactic instruction, which is so abundant in his poetry, were not just part of his professional life but also one of the features of his character.

It cannot be said that Donelaitis was a successful manager of the parish farm. Although he displayed much enthusiasm in his youth, in his later years he was not so much concerned with economic and agricultural affairs. Amtman Ruhig, in the court at Gumbinen in the separation litigation has made the following charge:

"He is completely ignorant of the quality of his fields and even more of their quantity, since during the 32 years of pastoral work and pastorate he was able to survey his fields only from a distance. His opinion and argumentation, which he presents in this litigation, are based only on the opinion of his bell-ringer Seligman and his servants, many of whom he even does not know adequately. And they (the servants) for a good word and other intentions are not ashamed to phan-tasize to him (Donelaitis) at his expense. These opinions in practice are completely impossible, but in their consequences nevertheless have a certain significance. Many pastors have already attempted to get rid of common fields and pastures, and have succeeded; only he of Tolminkiemis does not want to agree with this. Almost all estates in this area already have disengaged from common ownership".41

The precentor of Tolminkiemis parish, the Rev. Lovin, who came to the parish after Donelaitis' death, has also testified to the same effect: "This happening can be explained only by the carelessness of the just deceased pastor Donelaitis. He lived here from 1743 to 1780 and did not concern himself with the affairs of the farm, with his fields, or servants. Despite the carelessness of the Rev. Donelaitis, the frequent reports about the diminution of church lands depressed him considerably, for he found it necessary to explain, in minutest detail to his successor the circumstances of the decreasing church lands. But still he was not too much perturbed about this, and, according to his own admission, remained quiet and committed to God's will."42

It is evident from this that Donelaitis was not too interested in agricultural affairs and that the matter was not close to his poetic nature. He was even outraged at his confreres who were too concerned with economic matters, neglecting other pastoral duties. He wrote to his successor: "When the clergy concerned with earthly matters used to meet, rarely did the conversation turned to sciences and sermons; but the. talk about increasing profit and other earthly goods reached disgusting levels. I also, as my successor will be able to see from these notes, under depression have argued with others considerably, but this I did not for personal gain but only for the good of the parish and my successor."43

"By nature I had a lively temparament", wrote Donelaitis about himself. However, in old age as he himself admits, because of his hypo-chondrical tendencies, he was abnormally sensitive and nervous, sudden and impulsive. In one of the letters in the pastureland separation litigation, Donelaitis has expressed the following feelings about Ruhig: "Mr. Ruhig, that enemy of the people and my persecutor — that degenerate of the human race, with whom I have been acquainted since 1743. 1 have seen him even in my own house, when he, cap in hand, presented me with the orders from Amtman Behring, — this man is without conscience, this — this animal, this double revelation of hell and the devil himself . . ."44

After such outbursts, the poet expressed spiritual depression, sadness, fatigue, and apathy. As one of the students of Donelaitis, K. Do-veika, put it, "During such spiritual states K. Donelaitis has inscribed in various documents quite a few tormented lines, from which emerges the difficult life of the poet, full of hardships and disappointments. Through them speaks not the strict and quiet parson, but a man of many experiences and torments. From such soul-revealing statements emerges the variety and richness of the inner world of K. Donelaitis, the spiritual struggle with himself."45

Donelaitis was of clear Lithuanian disposition in respect to the germanization policies that were undertaken in his dav. When the rights of Lithuanian serfs were circumscribed in various ways, when it was attempted to eliminate Lithuanian language from public life, when government even took measures to protect the colonists from Lithuanian customs and costumery, Donelaitis stood as a staunch representative of passive resistance. He is one of the contributors to the beginnings of the Lithuanian national awakening in the eighteenth century.

Literary Heritage of the Bard

The principal literary work left by Donelaitis is The Seasons, a poem in four parts ("The Joys of Spring", "The Toils of Summer", "The. Harvest of Autumn", and "The Cares of Winter"). The poem, written in hexameter, which as yet has no established genre — sometimes regarded as idylls, sometimes argued suggestively to be realistic didactic poem, has little in common with the contemporary pseudo-classical or sentimental trends in Western European literature. In form, the work of Donelaitis seems to approach more nearly the classical literature of Greece and Rome. Hesiod, Theocritus, Virgil, and Ovid are the writers to whom the rustic poet of Lithuania Minor turned for poetic confidence, taking particular note of their poetic form. Seeking in remote antiquity models for his work and surpassing his own contemporaries in artistic ability, Donelaitis remained a faithful representative of his epoch. The rich life experience of Donelaitis, his deep religious commitment, the ethnic conflicts following the colonization are all reflected in his poetry — a realistic portrayal of his age and his people that approaches the preciseness of a historical document.

Donelaitis' realistic poem, portraying the life of the simple Lithuanian peasants, has a very limited but expressive vocabulary. The linguist and publisher of The Seasons Nesselmann has compiled a glossary of about 3,000 words used.46 This limited vocabulary was sufficient for Donelaitis to express the mentality of a simple boor, who could not possibly command complicated or abstract concepts. The vocabulary of a peasant is very clear in its purpose, suggestive, and without ambiguities. Such is also the vocabulary of Donelaitis — precise, rough, suggestive, and sometimes even profane.

When exactly Donelaitis wrote the four parts of the poem is not known, for he left no information on this. Apparently hee wrote the poem over a longer period, supplementing and correcting parts of the poem that were written earlier. The mentioning of the fires in Koenigs-berg in "The Cares of Winter" suggests that at least this part of the poem was written before 1769.47 The meticulous professor of literary history at the Koenigsherg University G. Pisanski, who documented in detail the literary facts of his day, mentions Donelaitis and his poem in Lithuanian language as having 659 lines. Pisanski's facts are also not dated. Since Pisanski died ten years after Donelaitis (1790), his information has contemporary significance. He indicates that there was a shorter version of The Seasons, which was even translated into German. (The final version of the poem has 2968 lines).48 In 1769 Donelaitis translated into Lithuanian official document in which he included two hexameter verses from "The "Toils of Summer". This suggests that Donelaitis was not only a liberal translator, but also that at least part of "The Toils of Summer" was already written in 1769. This is about the extent of available information on the dating of Donelaitis' crowning work The Seasons.

Donelaitis' work portrays mid-eighteenth century life of Lithuanian peasants in Lithuania Minor. The colonizations process had come to an end and the country, almost like a sea after a storm, was calm and sunlit. The country reached a comparatively high level of economical welfare. Not unreasonably, Frederick the Great described Lithuania Minor as a flourishing country, much more productive than any other province in Germany. The diversity of the population and their national differentiation was not as distinct any more. Separate groups of colonists, heretofore fighting for sovereignty, gradually fell silent, more and more adapting themselves to the new conditions of life and new people. Lastly, the native Lithuanian population of Lithuania Minor, although they had resisted the ingress of the newcomers into the conservative forms of their life, unconsciously became resigned to the idea; the youth was more easily swayed by foreign influences and gradually drew away from its heritage. Schools in common with the other nationalities created a situation where the Lithuanian from his early years was taught the German language, German culture and, most often, German religion. But all this did nothing to lessen the burden of servitude for the Lithuanian peasant, his moral humiliation and degradation.

Donelaitis' work as a whole shows the impact of colonization on life in Lithuanian Minor and depicts the Lithuanian peasant already swaying in various directions in response to the foreign winds. The old guard among the peasantry resisted foreign influence with all its strength, but even the physical limitation of its age, indicated the temporary and ineffective character of such action. The writings of Donelaitis present the conflict of national interests in Lithuania Minor; they show the last efforts of Lithuanians to preserve their individual, national, and ethnographic character.

At the same time, Donelaitis' work distinctly mirrors the social life of Lithuania Minor during the eighteenth century. On the one hand, there are the newcomer colonists; on the other — the native Lithuanian population consisting of landholders, officials, and Lithuanian serfs. In such a context of social differentiation Donelaitis presents the Lithuanian serf, though sighing on account of social injustice, but patiently and even with a certain pride bearing the burden of servitude. He shows the Lithuanian serf withdrawing instinctively into a conservative shell, defending the patriarchal traditions of his village; at the same time, he conveys the sense of the permeating foreign influences, Lithuanian degeneracy and susceptibility to assimilation. Tn this double encounter Donelaitis reveals not only the unconscious elements in the Lithuanian peasant, but the entire spiritual culture of the peasants and the end of its flowering. When Donelaitis confronts the social problem, speaks about the relationship between the estate and the village, a sense of hate directed at the colonist and the estate lord is discernible, but is clearly seen to flow from national and moral considerations. To the entire older generation of the peasants, with Prickus, Selmas, Krizas, and Lauras in the forefront, the new phenomenon of colonization with foreign people, foreign culture, a somewhat difficult moral sensibility, and even an economic and material framework that is alien and strange to the Lithuanian, was wrong and unacceptable, as every new phenomenon is unacceptable to a conservative mind. For this reason Donelaitis dislikes, rejects, and even condemns whatever new has been brought by the newcomers. He exhorts the peasants not to succumb to any suggestion the newcomers make, to keep unity among themselves, and to beseech God that He continue "to care in a fatherly manner" "in every need of ours." In this context, the unfriendliness and even hostility of the peasant toward the newcomer and the landholder, which Donelaitis displays, flows from the author's natural aspirations to safeguard values that are natural and innate.

In presenting aspects of degeneracy and loss of national identity in the village, Donelaitis has used strong and wrathful language. In the moralizing tone of the preacher, with all the ire, parody and caricature, hyperbolic image and expression that he was capable of, he denounced and condemned every effort by the peasants to acquire the characteristics of city culture. In Donelaitis' writings, a representative of such degeneracy in the village is seen as the source of all corruption and evil, a repulsive and revolting example. Therefore, such a person is rejected and cast out from the patriarchal village.

The Lithuanian village in The Seasons gives a clear picture of the patriarchal family. The village elder is not only the village administrator, but also the authority on all questions, counselor, and guardian. The village as presented by Donelaitis is a closely-knit community, even gives the impression of a single family unit: all work together, suffer together, enjoy themselves together. This close collective life, it seems, greatly contributes not only to the preservation of time-honored traditions, but to the general formation of the conservative character of the peasant. Not surprisingly, then, almost none of the characters in The Seasons possesses a distinct individual personality; all characters have become submerged in the community whether they exemplify the negative aspects of the village (Slunkius, Pelėda, Plaučiūnas, Dočys), or whether they are integrity incarnate (Krizas, Selmas, Lauras). Thus, we are not surprised to see Slunkius and Peleda come uninvited to the wedding of Krizas' daughter, where the whole village is in attendance. Their natural communal instinct is stronger than any sense of self-regard and shame. It would seem that this instinct would come into play just as strongly upon the sad occasion of a funeral, as at the happy festivities of a marriage. What brought the communal instinct of the Lithuanian peasant to the fore was most likely the invasion of the newcomer colonists into their patriarchal villages, their homesteads and houses. The ridicule that the newcomers expressed at Lithuanian dress and at their entire system of farming was a strong factor motivating the Lithuanian to seek the company of his own, so that together they could rebuff the jeers and contempt of the foreigners.

The characters in The Seasons, often revolving in the orbit of the author's own pastoral objectives, give a schematic impression. But even they display certain aspects that delineate them more sharply and leave an impression of integration and totality. Krizas, a type of the positive group, by the serenity and meekness of his character best represents the ideal of the pietistic Christian. In this sampling of rustics, he displays the quiet, passive nature of the Lithuanian, which is sufficiently strong to resist alien and, from the moral standpoint, injurious influence. This is a man of instinctive self-discipline; the aspirations of his uncorrupted nature will never accord with the burden of revolution or of progressive ideology.

A somewhat different type is the village elder Prickus. What distinguishes him most from the other peasants are his duties as elder, which help to reveal a more lively personality. Neither the dignity nor weight of these duties, but the balance in Prickus between his obligations as elder and his human conscience make him active and natural. Prickus is a lively and temperamental representative of village life in Lithuania Minor, who dominates the poem not only by reason of his important position, but by his own spiritual weight. His authoritative word in every matter is undisputed, respectfully accepted. Aside from the fact that he dominated the scene at Krizas' wedding festivities, speaking out openly about the life of the gentry and social injustice, he is by no means figure of arrogance and daring only. He is more authentic in the tragedy of his inner experience, which is concentrated in his comparison of himself, an aged elder, and an old "nag." He commands real sympathy when the author reveals the tragedy of his life: although he himself did everything to quench any dissatisfaction with the social order, he dies from a beating at the hands of the Amtsrat, as if pointing to the injustice of the social order.

Dočys represents truly individual thinking. The author created him as a purely negative village type: drunkard, pilferer, insubordinate, etc. In a link of pietistic characters, Dočys is a representative of the spirit of rebellion. Although the author does not conceal his disapproval of Dočys, the author's opinion must be mitigated to some extent, when we notice the implications of Dočys' words of defense in court:

"What

do you care . . . you dear superiors

If I sometimes desiring to fry crow's meat

Shoot a few crows for my dinner?

............................................

For you, .Sirs, have so abused us peasants

That very soon we will be eating rats and owls.50

Even though "Pričkus with other elders . . . wondered greatly, hearing such wonders," this is still a different tone in the grim era of serfdom, a manifestation of daring and rebellion, which if it had emerged from a positive situation, would have had an entirely different impact. In Donelaitis, however, he is only an accidental sample, a type of a certain insolence or too great expansiveness, and by no means a planned revolutionary figure. Dočys, in a certain sense a representative of positive thinking, is depicted by the author with a large number of vices. These vices and depravity that are piled on him and condemned in him by the author are most often intended to indicate that Dočys strove to overcome in himself the communal instinct, that in the patriarchal and conservative village he represented a distinct individual type. In his person we see no struggle between the communal attitude of the village and the individual force of his spirit. Therefore, Dočys comes out sporadic, a type of individualism and rebellion, without apparent or apprehensible spiritual conflict.

Although Donelaitis was not too concerned with characterization, some of his characters emerge quite clearly, with distinct traits in their practical existential surroundings. Plaučiūnas is an alcoholic, forever behind with his farm labors ; Dočys — always picking fights, arrogant, never afraid to voice his opinion; Enskys — cheerful and witty, always present at gatherings, enjoys telling intriguing stories; Slunkius — an idler with a "philosophy" of his own about a swiftly turning wheel and "a slow nag." It appears that this "philosophy" is convincing only to .Slunkius himself.

Donelaitis is a poet with a clearly defined intellectual objective and definite moral didacticism; in any darkness, therefore, he will always attempt to let in a ray of light. Although his negative characters arc more human and more interesting, they are drawn in dark colors only and bring upon themselves harsh words of condemnation. Only the creative talent of the poet unconsciously reveals certain character-istic nuances of the human scale.

The peasants of the Vyžlaukis county, whose life Donelaitis depicted in his poem, are simple boors, "miserable," "stinking," "wretched." Sometimes the poet teaches and scolds them, at other times he sympathizes with them and praises them. The poet was sincerely in love with the booted "little Lithuanian wretch" of the serfdom age and. led by these feelings he wrote for them a song, which even a nightingale in the forests of Rominta has never sung.