Editor of this issue: Thomas Remeikis

Copyright © 1964 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 10, No.2 - Summer 1964

Editor of this issue: Thomas Remeikis ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1964 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

DR. POVILAS REKLAITIS

POVILAS REKLAITIS, Lithuanian art historian, a frequent contributor to scholarly journals, holds a Ph. D. from University of Tuebingen (1949). His latest work is: Einfuermig in die Kunat-gesckichtsforschung des Grossfuerstentuma Litauen, Marbug-Lahn, Herder Institute, 1962.

THE PROBLEM OF THE EASTERN BORDERS

OF GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE

Historical Background

In the middle ages, Europe was not homogeneous; it was divided into the East and the West. The loss of a unifying factor is presupposed in discussing this division: during the final days of antiquity, the factors fostering the unity of Europe were the Roman Empire and her conceptual counterpart, the Christian Church which had enveloped all of the Roman Empire by the third century A.D. The divisive process began early, for the inner structure of the Roman Empire was heterogeneous from the standpoint of nationality: it ruled a large number of nations of diverse origins. The Greek and Roman nations contributed most, both spiritually and materially, to this culture: the Latin and the Greek languages existed side-by-side in the Roman Empire. In this national and linguistic division lies the first cause of the split within Europe

The cleavage of the Roman Empire was also fostered by the administrative - national politics of the Roman Emperors. The first steps toward the division were taken by Emperor Diocletian as early as the year 294 A.D. Constantine the Great having restored the unity of the Empire, in 330 A.D. established his residence in Byzantium, the Greek city near the Bosphorus, which then became Constantinople. Thus Constantine laid the foundation of the Eastern and Byzantine Empires. Rome, no longer the capital, lost power, prestige, and population. The testament of Theodosius the Great finalized the partition of the Empire into the Western - Roman and the Eastern - Byzantine Empires. The weak West soon fell into the hands of the Teutons. The Western Empire ceased to exist in 476, while the Byzantine Empire survived until 1453. The Western Empire was restored on a new foundation through the crowning of the Erankish king, Charlemagne, as Emperor by Pope Leo III in the year 800. The traditions of this essentially symbolic empire, subordinate to the Pope at Rome and consecrated by the Church — "Sancrum Imperium" — were maintained by the German Emperors in the West during the Middle Ages.

Of most consequence to the spiritual life and culture of that period was the division of the Church into Eastern and Western factions — into the Church of Rome and that of Constantinople, — which occurred during the early Middle Ages. Administrative difficulties again were the cause of this rift, especially those evident in the ninth century, in the lawsuit of Patriarch Photius during the ratification of the Patriarchy of Constantinople and culminating in the theological quarrel that resulted in complete schism in 1054. Several liturgical differences contributed to this schism, including the worship of icons and the difference in liturgical languages: Greek in the East, and Latin in the West. In the evolution of history, the Eastern, as well as the Western Church proved to be more enduring than the extension of the unity of the Roman Empire in the political sphere. In the West, the primary unifying factor of European civilization during the entire Middle Ages was the Roman Catholic Church with its Popes, who had managed to convert to their ideals people of different origins — the Teutons and the Neo - latin peoples.

This break between the East and the West was of great significance to the nations of northen Europe which were inevitably drawn into differing cultural orbits, either by the West or by the centers of the Eastern Empire. While the northern Teutonic, western Slavic and the Hugarian nations fell under the jurisdiction of the Roman Catholic Church and were bound by political ties to the German emperors, the Rumanian, part of the southern and eastern Slavic nations followed the Eastern Church which had been formed by the Greeks and surrendered to the influence of the Byzantine civilization. The marginal part of the eastern Slavs, which colonized the nations of Finnish origin in the northeastern territories, became the new Russian nation during its expansion and turned against the West with a threatening force. The antagonism between the East and the West was not merely limited to the religious and political spheres, but determined a series of deep-rooted differences within the entire spiritual and material - technical culture. These differences were most apparent in art, particularly in architecture.

By the thirteenth century, both worlds had assumed their positions on the line which stretched from Finland down to the Adriatic Sea. The only European nation which had not made its choice by the beginning of that century was Lithuania. In the thirteenth century and particularly during the reign of King Mindaugas (d. 1263), Lithuania's ties with the West became increasingly stronger, despite the fact that the political orientation of the Lithuanian rulers remained opposed to Western Europe for the next hundred years or more.1 By the thirteenth century, two Latin - Catholic dioceses had been established in Lithuania and appropriate Western military and civil construction methods had been initiated. As Lithuania turned to the West, the first consolidation of the great cultural line of demarcation occurred.

Despite the colossal differences between the two cultures, this boundary line was still not rigidly defined, but had a peculiar and complex history during the fourteenth and the fifteenth centuries. It was influenced by political events, economic changes, religious and artistic currents from either side. Lithuania's geographical position was continuously changing — the culture itself, which existed near this line, was always assuming new-patterns in the religious, artistic, and technical areas.

The history of architecture indicates that in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the Gothic architectural style took form in the West and soon spread over the entire Western World. Of all the Western architectural styles, Gothic architecture in its structural system and architectural decorations and ornaments stands furthest removed from the Eastern Byzantine architectural style. Thus, the spread of Gothic architecture most vividly symbolizes the unity of Latin - Western Europe. Any attempt to explain the development of Western culture in the realm of architecture must first be preceded by the resolution of the problem of Gothic architecture's eastern borders.

Treatment of the Problem in Art History

Interest in the eastern borders of Gothic architecture developed rather late and even today this question is not fully answered in all of its ramifications and details. The reason behind this prolonged lack of interest in this question lies in the idealistic character of the history of art (to which the history of architecture naturally belongs). Academic art history, having developed from art theory which seeks ideal models for artistic creations and from aesthetics which seeks to experience perfect beauty, concentrated its attention upon the most perfect products of artistic creativity — the masterpieces. Having established the search for the highest artistic value as its object and goal, academic art history was not interested in the totality of the arts without having first made its selections according to qualitative evaluative criteria. For this reason, art history, not having complete statistical data, was not able to explain more precisely the various aspects of the diffusion of art objects. Even today, art history has still not become as completely a part of history of culture as it must, if it is to remain a science.

For a long time, Western art history almost ignored the architecture of the Western World's eastern territories, either completely circumventing it or noting it only in passing, as if it were something of little significance. Therefore, Western art history has long been unable to clarify the phenomena of its own Western culture such as Gothic arcitecture and the issue of boundaries and territorial limits which were delineated inaccuratelly in textbooks and atlases. In the best French and German art history textbooks printed in several editions before the first World War (those of Michel, Springer, Weor-mann, Luebcke, and others) one finds only a few lines or no mention at all of the monuments of the Baltic countries, Poland, or Hungary. (Furthermore, the latest books on the synthesis of the history of Western architecture such as that of Pevsner (1957) or of F. Baumgart (1960) completely ignore the architecture of these lands which belong to the Western tradition.) It is true that no specific studies of the artistic monuments in the eastern countries have been made for a long time. It was impossible to prepare such studies because the countries on the eastern border of the Western World were under foreign domination. Secondly, the explanation of the geographic boundaries of the expansion of any artistic form is not the task of art history as much as of art geography. But art geography is a relatively new science. A serious reason prevented its development earlier — the lack of a systematic inventory of art monuments, which was begun in Western Europe in Alsace around 1870 and which has not yet been fully completed in all countries.2 Such inventories were and are lacking for the countries at the eastern border of Western culture.

Polish Studies of Eastern Borders of Gothic Architecture

The situation began to improve after the first World War, when several nations at the eastern border of the Western World regained their independence and began to carefully investigate their cultural-artistic heritage through individual studies and through systematic inventories of their entire artistic heritage. The Poles initiated the overall examination of the problem of the eastern border of Gothic architecture, for during the period of 1920-1939, an important part of this border existed within Poland.

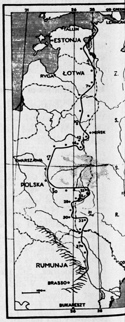

In 1935, the bulletin of the Technical University of Warsaw published an interesting map (1:10,000,000) called "The Expansion of Gothic Architecture in Eastern Europe (from the Baltic Sea to the Carpathians.)" The map was prepared according to the findings of a group of art historians (J. Dutkiewicz, St. Herbst, St. Lorentz, Ks. Piwocki, O Sosnowski, M. Walicki). This map represents the first attempt to employ cartography in special investigations and studies designed to explain problems of a wider scope.3 The publishers had planned to prepare additional maps which were to comprise a special atlas of the history of Polish art and culture. A total of 40 Gothic architecture border monuments were listed on the published map. (See Illustration No. 1 for the geographic location of monuments listed below).

|

| 1. Eastern border of Gothic architecture, from the Bay of Finland to the Carpathian Mountains. This map was published by Polish scholars in 1935. |

Estonia:

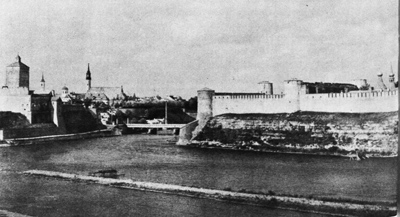

1. Narva. A castle (See Illustration No. 3).

2. Vasknarva (Neuschloss in German, Sereniec in Russian) A castle.

3. Tartu. A castle.

Latvia:

4. Aluksne (Marienburg in German). A castle.

5. Vilaka (Marienhausen in German). A castle.

6. Ludza (Ludsen in German, Lucyn in Polish). A castle.

7. Volkenberga (Walkenburg in German). A castle.

8. Daugavpils. A castle.

Lithuania

- Belorussia:

9. Kamojys (Komaje). A church.

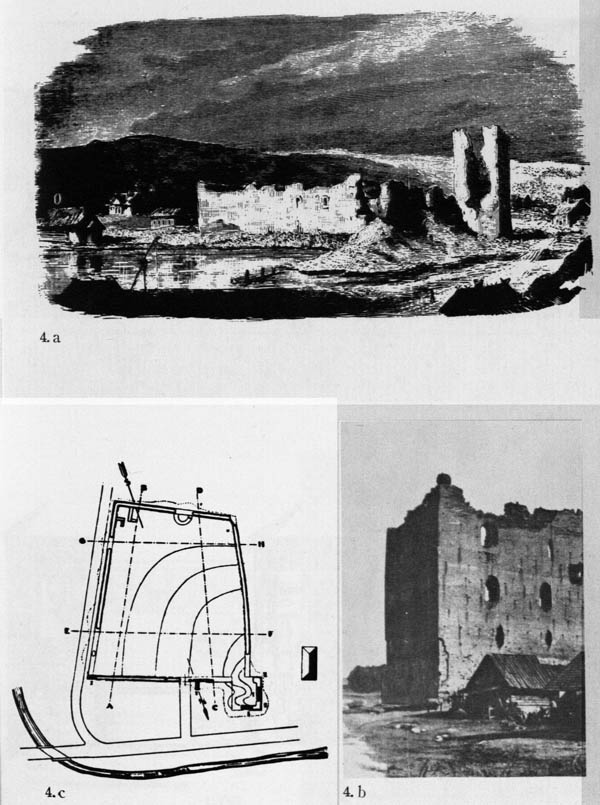

10. Kriavas (Krewo). A castle. (See Illustration 4a, 4b, 4c).

11. Kaidanava (Kojdanow). Protective wall of a church.

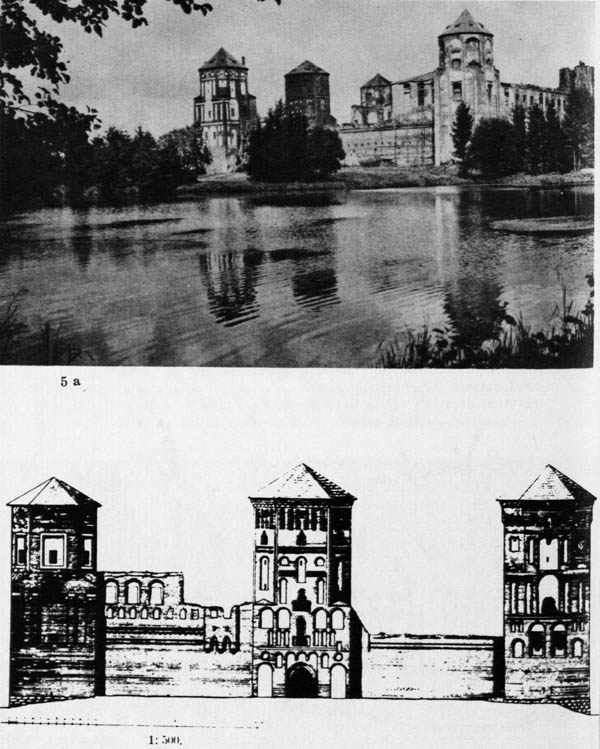

12. Myrius (Mir). A castle. (See Illustration 5a, 5b, 5c).

13. Kleckas (Kleck). A castle. (See Illustration 6).

14. Iskolde (Iszkoldz). A church.

14. Sinkoviciai (Synkowicze). Protective Orthodox church. (See

Illustrations 7a, 7b).

16. Ilniczno. A church.

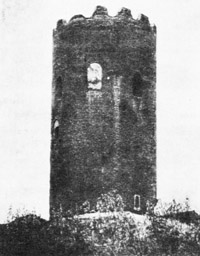

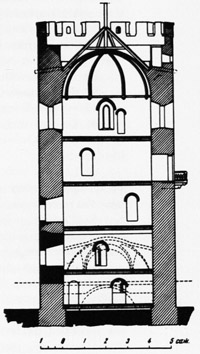

17. Lietuvos Kamenecas (Kamieniec Li-tewski). Tower. (See Illustrations

8a, 8b).

18. Kodenas (Koden). Orthodox church.

Poland:

19. Bielawin. A tower.

Ukraine:

20. Zimno. Orthodox church.

21. Luck. A castle.

22. Klewan. A castle.

23. Ilubkov. A castle.

24. Korzec. A castle.

25. Ostroh. A castle and an Orthodox church.

26. Miedzyrzecz Ostrogski. Orthodox church.

27. Nowomalin. A. castle.

29. Zbaraz (?). A castle.

30. Trembovla. A castle.

31. Me■ibiz (P. MiŠdzyboz) (?). A castle.

32. Leticev. A church.

33. Sutkivce. A protective Orthodox church.

34. Kamenec-Podolsk. A castle.

Rumania:

35. Chocim. A castle.

36. Dorohoj. Orthodox church.

37. Botosani. Orthodox church.

38. Havlan. Orthodox church.

39. Roman. Orthodox church.

40. Bacau. Orthodox church.

0. Sosnovski has already attempted to draw several conclusions from this first cartographical work on the eastern borders of Gothic architecture:

1.

The eastern boundary line is oriented directly

North-South. Only the areas such as the lowlands of Polesic and the

swamps at the upper part of rivers

Horyne and Bug are circumvented by this line and remain to the East of

it, because these area were less accessible and thus less influenced by

the Western civilization.

2. This boundary line, stretching from the Baltic Sea to the

river Dienster, follows almost exactly the political border of the

Soviet Republic as it existed in 1935.

3. Thus, Latin civilization which had been documented during the Middle

Ages by Gothic architecture, appeared in the waning

days of this epoch in the confrontation - zone of two diferent and

opposing cultures — those of Europe and

of Eurasia. On one side, this zone was represented by Estonia,

Latvia, Poland, and Rumania; on the other, by Russia.4

We should be surprised by the fact that Sosnovski said not a word about the significance of the Lithuanian group of Gothic monuments — a significance which was clearly apparent from this map. Thus, his assertion that, through some natural determinism, the architecture of the Latin West had to take a detour around the swamp region cannot convince us. In the seventeenth century when the historical situation had changed, why did the Jesuits build an extensive college campus, monastery, and church in Pinsk, the very center of the cited swamp region? Of much greater import and significance is the fact that the Lithuanian nation, having maintained the ancient pagan religion within its ethnic borders until the 13th -14th centuries and not having surrendered to the mission of the Eastern Church, preserved the necessary vacuum for this space, which the Roman Catholic religion and the Western Gothic could easily and widely occupy in the 14th-15th centuries, beginning with the capital, Vilnius. In the 15th-16th centuries, the Gothic style spread into the East and the South. The cultural activity of Lithuania and Vilnius was so dynamic, that in several places the characteristic qualities of the Gothic style conquered the religion and language barriers and had influenced the architecture of some border areas of Belorussia. That the contrary did not occur in this border area between the East and the West is the contribution of the Lithuanian nation: a contribution ignored by the Polish scholar, even though it is clearly evident in the flow of the Gothic architecture's boundary line.

German and Ukrainian Studies

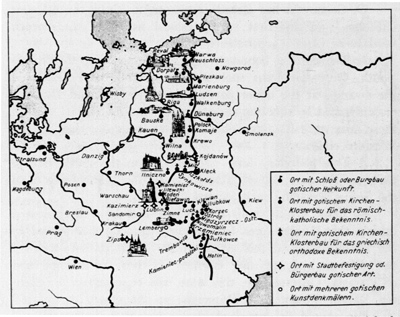

An illustrated map, "The Borders of

Gothic Architecture" was published

in 1939 in the German publication Euro-pa und der Osten.5 (See

Illustration No. 2). It was clearly drawn using the cited map published

in the bulletin of the Technical University of Warsaw, for the sequence

of the border monuments as well as the course of the very boundary line

to the North, into Finland and to the South, into Sep-tynpilis,

Hungary, and Croatia was not shown ; this also indicates that the

authors of the German publication based their work on the map prepared

by the Polish. However, the German map offers some additional

information. Individual monuments are marked by special signs such as:

2. Eastern border of Gothic

architecture. This map was published by German scholars in 1939.

Even though the supplementary information is usually provided in visual, illustrative form, the statement about the Gothic architecture in Pskov merits further notice. The towers of Lietuvos Kamenecas (Kamenec Litewski) and Bielawin are identified as fortifications. This is unacceptable, because these towers are most likely the remains of old castles and not of a city.

In 1942, Dmytro Antonowytsch, an Ukrainian art historian, criticized this German map of the Gothic eastern border, but did not note the Polish origin of this map.6 In his opinion, the above-mentioned German map needs correction with reference to the Ukraine, where Gothic monuments are found much further to the East. The German and Polish literature persistently maintains the false idea that Gothic monuments are found only in the western part of the Ukraine, while Gothic architectural monuments are found throughout all of the Ukraine, such as the once famous "Lithuanian castle" in Kiev, destroyed with all of its contrivances in the seventeenth century. The Dominican Church of St. Michael in Kiev, which was finished in 1610, was also Gothic. It had a three-bay hall with a high roof and high windows with pointed arches. This church was destroyed only in this century by the Communists. "Far across the Dniepr, in the Lubny residence of the ducal Visniavecki family, all of the stone architecture had a pure Gothic form at the end of the sixteenth century and during the first half of the seventeenth." 7 According to Antonowytsch, all of the stone buildings in the Ukraine, built between the fourteenth century and the first third of the seventeenth, were Gothic. Because of the many Tartar assaults, however, only a few of these buildings have remained. Beyond the delineated Gothic eastern border, remains of Gothic castles and fortresses are found in several other places such as Svjahel, Ůitomir, and Bar.8 If the facts presented by Antonowytsch are accurate, they completely negate the conclusions drawn by Sosnowski.

A Critical Conclusion

The first attempts to map the eastern border of the Gothic style and the critique of these attempts demonstrate the complexity of this problem: so far, the basic premises have not been fully explained. Specific investigations and correctly dated chronologies of many monuments are lacking. A good part of the monuments ascribed to the Gothic style are of a considerably later period and belong to the second half of the sixteenth century or even to the seventeenth. Can one agree with Anto-nowytsch's opinion that until the seventeenth century, the provincial masons of the Ukraine were trained only in the Gothic tradition and thus all of their buildings in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries can automatically be classified as Gothic? To support his conclusions, Antonowytsch does not present any precise criteria for the classification of Gothic masonry techniques. A detailed analysis of the form of every monument is unavoidably necessary. Without it, one cannot answer the question whether the Renaissance movement of the new epoch, which changed the construction of castles and churches, had reached the Ukraine and Lithuania in the sixteenth century. What is the true origin of the Gothic form of the monuments which remain in our land?

The structural concept should be the basic principle in establishing the eastern border of Gothic architecture. A different problem is presented by the geographical distribution of individual Gothic structural elements and ornamental motifs. The ornamental elements (friezes, niches, shapes of arches, portals, bas-reliefs) of the Western Romanesque style had already penetrated far into Russia during the twelfth century.9 Later, the Gothic style strongly influenced Novgorod, which contained a Hanseatic colony and had broad commercial traffic with the West. Archbishop Euphimius, a supporter of the independence of the republic of Novgorod and an enemy of Moscow's imperialism, built a stone palace in 1442; its great hall, with Western-style, pure Gothic ogive, diagonal groin rib-vaults, spouting from a pilaster in the center of the hall still stands.10 Similarly vaulted halls existed in the donjon of the Kriavas (Krewo) castle in Lithuania and in the Gothic buildings near the Convent of St. Catherine in Vilnius. The Archbishop's hall in Novgorod, which had been used for the official meetings of the nobility, was decorated with frescoes, just as the earlier ceremonial hall of the lake Galve castle in Trakai near Vilnius, Lithuania.

These examples show that the resolution of the problem of the expansion of Gothic forms demands minute re-examination of monuments on both sides of the hypothetical eastern border of Gothic architecture.

4. The castle of Krewo (fourteenth

century). The

defensive walls axe of irregular trapezoid construction,

a) A view of

castle ruins, from a nineteenth century engraving,

b) Photo of the

donjon, ca. 1910.

c) The plan, according to St. Lorenz, 1930.

5. The castle of Mir (beginning of

sixteenth

century),

a) A view from the lake-side, ca. 1910.

b) Western facade,

1:500, according to B. Schmid.

c) The plan, 1:1000, according to B.

Schmid, 1942.

6. The castle of Kleck, from an

engraving by T. Makovski, ca. 1600.

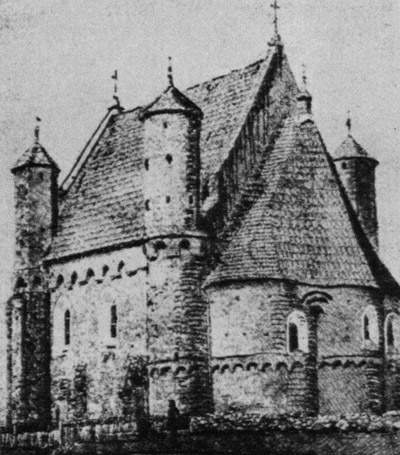

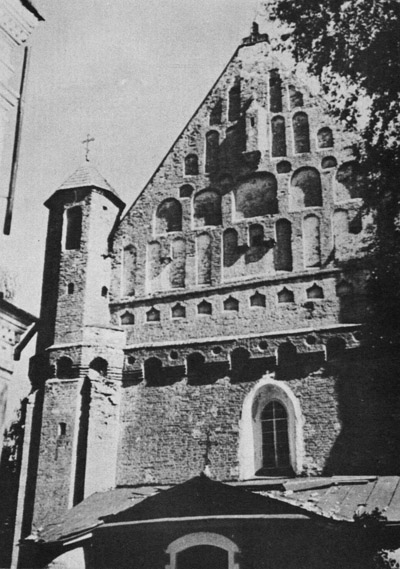

7. The defensive church of Synkowicze

(beginning of sixteenth century),

a) A view from the side of the

prisbyter.

b) Western facade.

NOTES

1 J. Stakauskas, Lietuva

ir Vakar° Europa XIII-me am■iuje - (La

Lithuanie et L'Occident au XIIIe siecle), Kaunas, 1934, p. 261.

2 D. Frey, "Geschichte und Probleme der Kultur-

und Kunst-geographie", Archeologia

Geographica, Hamburg, 1955, Vol. IV, p. 96.

3 "ZasiÓg budownictwa gotyckiego na wschodzie Europy (od Baltyku do

Karpat)" (La limite Est de l'expansion

territo-riale de l'architecture gothique en Europe (ligne: Mer

Maltique-Carpathes)), Biuletyn

Historji Sztuki i Kultury, Warszawa, 1935, Vol. III,

No. 3, pp. 166-167.

4 0. Sosnowski, "Prace kartograficzne" (Les travaux

carthographques), Biuletyn

Historji Sztuki i Kultury, Vols. XV-XVI, pp. 165,

168.

5 H Hagenmayer und G. Leidbrandt, "Die Ostgrenze der gotischen

Baukunst", Europa und

der Osten, Muenchen, 1939, p. 142 (2nd ed.

1942).

6 D. Antonowytsch, Deutsche

Einfluesse auf die ukrainische Kunst,

Leipzig, 1942.

7 Ibid., p. 24.

8 Ibid., p. 25.

9 F. W. Halle, Russische

Romanik: Die Bauplastik von Wladimir-Sausdal, Berlin,

1929.

10 W. N. Lasarew, Die

Kunst Nowgorods, "Geschichte der

russischen Kunst", vol. II, Dresden, 1958, p. 52.