Editor of this issue: Thomas Remeikis

Copyright © 1965 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 13 11, No.3 -

Fall 1965

Editor of this issue: Thomas Remeikis ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1965 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

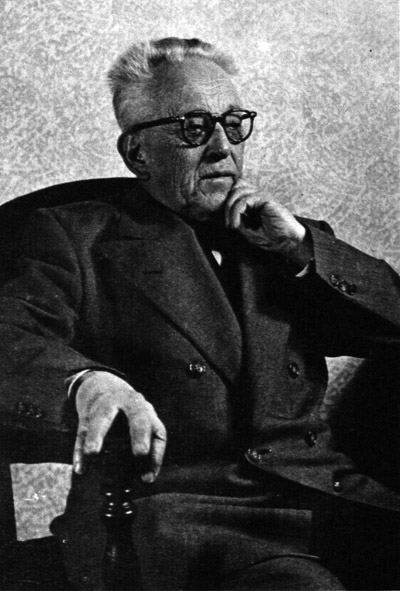

VINCAS KRĖVĖ, THE LITHUANIAN CLASSIC

BRONIUS VAŠKELIS

Lafayette College,

Easton. Pa.

|

In the history of Lithuanian literature Vincas Krėvė1 occupies a most prominent place, acknowledged by literary specialists in the West as well as in the East. He was one of initiators of modern Lithuanian literature and became its major figure. During the 1930's, at the peak of his creative activities, his works were already considered classics and he himself as a typical national writer of Lithuania. Although many changes took place following the War World II and during the current occupation of Lithuania, his works still remain popular among his compatriots; he stands above the change of taste and time.

I

Krėvė's personal biography is complex and extremely eventful.2 He was born on October 19, 1882 of a Lithuanian peasant family in a village of Subartonys. Merkinė district in Southern Lithuania.3 That part of the country is famous for its picturesque and lyrical landscape, its historical and legendary burial mounds and castle hills. In childhood Krėvė apparently absorbed many of the legends and rich folklore of the region which served as continual inspiration during his entire literary career.

Upon completion of elementary school in Merkinė and after instruction from a tutor, he passed four years secondary school examinations in 1898 and entered into a seminary for priests in Vilnius. Two years later he left the seminary. After continuing his education privately, in 1904 he received the secondary school graduate certificate in Kazan, Russia. In the same year he enrolled in the Department of history-philosophy of the University of Kiev. When the university was closed, because of the 1905 revolution, Krėvė left for the University of Lvov (then in Austria-Hungary) and majored in comparative Indo-European philology. He graduated from Lvov with a degree of Ph.D. in 1908. In order to teach in Russian universities he had to defend his thesis4 at the University of Kiev. Because of a variety of circumstances which are not entirely clear, he did not teach in Kiev, but moved to Baku in 1909 where he taught Russian language and literature in a Russian secondary school.

While teaching Krėvė also continued his Oriental studies in absentia at the University of Kiev which he successfully completed in 1913 after defending his master thesis about origin of Buddha and Pratjekabuddha names. After the Russian revolution in 1919 the government of Lithuania appointed him consul in Baku, capital of then established republic of Azerbaijan.

Since his return to Lithuania in 1920, Krėvė played a major role in Lithuanian cultural and academic life. For first two years he worked in the Ministry of Education, on the committee for publication. After founding the university of Kaunas in 1922. he became Professor of Slavic literatures, 1922-40 in Kaunas and 1940-44 in Vilnius. He was Dean of the Faculty of Humanities from 1923-37 and in 1941 became the first President of the Lithuanian Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1940, during the first weeks of the Soviet occupation, Krėvė served as Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs of Lithuania. Although, unable to preserve the independence of the country, because of the Soviet ready-made policies, he resigned from the two posts and, shortly before the second Soviet occupation of 1944, left Lithuania. After a sojourn in displaced persons camps in Austria, he was invited in 1947 to join the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania, where he taught Slavic and Lithuanian literatures until his retirement in 1953.

He died July 7, 1954, in Marple Township, a suburb of Philadelphia.

II

Krėvė's literary activities are as numerous and complex as is his personal biography. In the annals of Lithuanian literature he was a major and domineering figure throughout a period of fifty years. Moreover, he was well known as an editor of various literary and cultural magazines,5 including the main publications of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Kaunas.6 In these publications and magazines his own articles on culture, theatre and literature were published. In addition to this, he worked, especially in his student days, as a compiler of Lithuanian folklore and later as an editor, publishing material he or others gathered.7

The beginning of Krėvė's literary career may be regarded as the year 1904, when he wrote in Lithuanian his first sketch "Miglos" ("Fog"), published later in a magazine "Vaivorykštė" ("Rainbow", 1913). His earliest writings, consisting of various sketches and stories, were collected from various magazines and published in 1921 under the title "Sutemos" ("Dusk").8 It is notable that during his studies in Lvov he wrote few verses and stories in Polish, which appeared under the pen name of Wajdelota in the collection "Frustra" (1907), published together with two of his friends: A. Krasowski and M. Woroniecki.

Major characteristics of his earliest writings are frequent digressions into reveries and a world of distant past, juvenile lyrical experiences, reflective and sad moods. Many of them possess romantic and symbolic connotations. Despite their fragmentary and immature manner of presentation, these works already exhibit Krėvė's major characteristics, often found in his later writings, such as, usage of Lithuanian folklore motifs, attraction to nature, a great concern with human feelings, especially with love, beauty and vitality of passions.

These aforementioned characteristics found their best expression in already mature and brilliant works: namely, "Dainavos šalies senų žmonių padavimai" ("The Tales of the Old Folks of Dainava", 1912,9 and two dramatic plays, "Šarūnas" (1911)10 and "Skirgaila" (1925).11

Chronologically, some tales of "Dainavos padavimai" date back to the period of his earliest writings. Out of eight tales, included in that collection, "Gilšė" (a name of the lake near Krėvė's native village) was published earlier in the newspaper "Viltis" ("Hope", 1909). To the third edition of this collection (1928) Krėvė added two more tales: "Kunigaikštis Ku-notas" ("Prince Kunotas") and "Sena pasaka apie narsųjį kunigaikštį Margirį, Punios valdovą" ("An Old Tale about a Brave Prince Margiris, the Ruler of Punia"). The subject matter of the tales is drawn from distant past of Lithuanian history, and from legends and tales, related to Krėvė's native district of Dzūkija. For his romantic and historic content he employs various stylistic devices of Lithuanian folk songs and tales successfully adapting them to compositions of the tales and idiosyncrasies of characters in the tales. As a result Krėvė has created an original literary style of a romantic folk ballad. In addition to an idealization of princes' feat of arms and battles of legendary brave heroes, Krėvė extols strong-willed, ardent individuals who are fearless in facing death and determinate in rebelling against their own destinies.

Krėvė's dramas "Šarūnas" and "Skirgaila" may be regarded as sequels of "Dainavos padavimai". The plot of the former is constructed around legendary prince Šarūnas, a man of rebellious and strong-willed nature. To achieve his personal ambitions, one of which is to unite all tribes of Lithuanians into one state, Šarūnas breaks moral and social laws and old cherished traditions. The focus of the play is placed on Šarūnas' inner dramatic struggles which are conveyed mainly by dialogues and allusions rather than by overt actions. Trying to create atmosphere and mode of life of ancient Lithuanians, Krėvė extensively uses folk songs, lengthy descriptions of traditions and various ethnographical features. This play, therefore, belongs rather to a genre of closet drama.

The play "Skirgaila", first written in Russian (1922) and later rewritten in Lithuanian (1924), is more realistic in regard to treatment of subject and presentation of the past, than, for instance, is the play "Šarūnas". The major figure of "Skirgaila" is already the historical prince Skirgaila. He is presented as an astute and practical politician, a man of reason, controlling his own desires. "Skirgaila" is also a brilliant tragedy of well-knit composition and Shakespearean overtones ; it may be considered one of the best plays in Lithuanian literature. To depict individuals, caught in turmoil and throes of changing times. Christianity replacing paganism, Krėvė uses extensively methods of various contrasts and parallelisms. For instance, characters of the Christian world are balanced by similar or contrasting ones of the pagan Lithuania. It is notable that those who practice perfidy or cruelty for good of their country and those who choose love instead of fidelity do not appear as villains.

To the same trend, the probing history and charting destiny of the nation, belong Krėvė's two later written plays: "Likimo keliais" ("On the Paths of Destiny")12 and "Mindaugo mirtis" ("The Death of Mindaugas", 1930).13 The first act of "Likimo keliais" appeared in the magazine "Skaitymai" ("Readings") already in 1921. The complete play was published as a book in 1926-29 after many revisions and expansions. It is a lengthy, rather obscure mystical drama which tends to interpret symbolically the entire history of the nation. Similarly, the tragedy "Mindaugo mirtis" does not reach the artistic and dramatic level of "Šarūnas" and "Skirgaila". The play is well-structured, dramatic, presents intriguing situations and conflicts, yet lacks depth and vigor.

Ill

In addition to Krėvė's preoccupation with Lithuanian historical and legendary past, he explored with inquiring interest and probing psychological insight the rustic life of his own region of Dzūkija, as it has existed at the turn of the century, and city and village life of the independent Lithuania. His rustic experiences were the inspiration for the following three remarkable works: the collection of short stories "Šiaudinėj pastogėj" ("Under a Thatched Roof", 1921),14 the novellete "Raganius" ("The Sorcerer", 1939)15 and the play "Žentas" ("The Son-in-Lavv")16. The modern life of independent Lithuania resulted in only two less significant works: the .short story "Miglose" ("In the Fog", 1944)17 and the collection of eleven short stories, published posthumously under the title "Likimo žaismas" ("The (Game of Destiny", 1965)18 To this category of works may be added the story "Pagunda" ("The Temptation),19 published in 1950 under the pen name of Vincas Baltaūsis. Journalistic in treatment of this subject, it depicts a specific Soviet technique, recruiting people for propaganda purposes.

The collection of "Šiaudinėj pastogėj" consists of twelve short stories previously published in various magazines. The earliest story "Bobulės vargai" ("Grandma's Worries") appeared in the newspaper "Viltis" ("The Hope") in 1909. These stories are based on peasants' insignificant, everyday activities, focussing attention primarily on the psychological and moral problems. The social problems of peasantry are entirely ignored. Moreover, the stories are more realistic in approach and treatment of the subject matter than, for instance, his tales in the collection "Dainavos padavimai". Krėvė's characters, living in close contact with nature, are almost untouched by modern civilization and its inhibitions. Nevertheless, they appear as distinct individuals with firm beliefs and primitive ways of life. The most characteristic feature of the stories is simplicity in plot, composition and narration. The plot often consists of a single event of few insignificant episodes ; this is especially noticeable in his realistic stories. The story usually unfolds according to natural events in place and time and the author serves as narrator. Though in some stories, namely, "Bedievis" ("The Atheist") and "Skerdžius" ("The Herdsman"), Krėvė occasionally inserts romantic and lyrical descriptions of nature as he envisioned it when he was a youth. Moreover, Krėvė's language attributes a great deal to his effective and vivid narrative style. Avoiding intellectual and refined discourse, he had created a powerful medium of expression which is akin to colloquial speech, especially in syntax, vocabulary, stylistic devices and at the same time melodious, picturesque literary language.

The same milieu and similar formal aspects are applied in Krėvė's novellete "Raganius", published in 1939, fragments of which began to appear in magazines since 1930. The novellete consists of six parts, each of which may be regarded as a separate short story. The unity of the novellete, however, is maintained by the shepherd Gugis, the central figure, who appears in each section and gradually exposes his own complex and original personality. The most notable feature of Gugis is a complete reliance upon his intuition, wisdom and experiences rather than wealth, religious rituals and the opinions of others. In the "Raganius", in contrast to stories in "Šiaudinėj pastogėj", we encounter a wider panorama of peasant life, especially with regard to social conditions.

Krėvė's realistic, eight' part play "Žentas" also deals with rural life. The parts of "Žentas", occuring at different places, portray different aspects of a specific environs, such as, peasant living quarters, an office of a rural district, a parsonage, a provincial town's inn and a church yard. In spite of the fact that not all parts of the play are equally successful, i. e., in mastery of stage techniques, creation of dramatic tension and psychological and moral conflicts, Krėvė still depicts a mode of peasant life in a vivid and somewhat idealized manner.

In the story "Miglose" the rural life of the independent Lithuania is depicted in a rather somber color. The plot consists of a few episodic experiences of the central figure, Griaužiūnas, who returns to his native village after a long absence. Krėvė's treatment of themes is so superficial, his character delineation is so sketchy that one hardly recognizes Krėvė's usual literary excellence. Similarly, the collection of short stories "Likimo žaismas", concerned primarily with city life, lacks coherence, fervor and psychological insight.

IV

Although Krėvė's previous works have concerned Lithuanian historical and legendary past and contemporary time, the third aspect of Krėvė's creative activities extends far beyond his native material and milieu. Since he was well acquainted with Oriental thought and literature and with the development of Christianity, Krėvė devoted a considerable part of his literary career to study of man and his spiritual life in Oriental and Biblical times. The results of these studies were two remarkable works: the collection of tales "Rytų pasakos" ("Tales of the Orient", 1930)20 and "Dangaus ir žemės sūnus" ("The Sons of Heaven and Earth". 1907-1954).21 "Rytų pasakos" consists of five stylized ancient Indian and Persian legends, from which "Priešingos jėgos" ("Opposing Forces") appeared already in "Frustra" (1907). Their exotic subject matter and problems, concerned with man's spiritual life, attest to Krėvė's strong romantic inclinations. In addition, he deserves credit for introducing the Oriental style to Lithuanian literature.

"Dangaus ir žemės sūnūs" is a Biblical epic on which Krėvė worked periodically from 1907 to his death. However, only the first two volumes of three originally projected, have been completed. Several fragments were published until the first volume under the subtitle "Žemės vingiais" ("On the Windings of Earth") appeared in print in 1949.22 The second volume together with several unattached fragments were published posthumously in 1963.

The first volume of "Dangaus ir žemės sūnūs" is composed of eleven parts, from which the first part functions as a prologue. The setting of the prologue is in heaven, while actions of the remaining parts take place in Palestine, spread over the time from Christ's birth till the death of Herod. The second volume, consisting of eight parts, ends somewhat abruptly and one wonders whether Krėvė considered it as a completed volume. The backbone of the plot is life of Jeshua (Jesus Christ), who is already in his teens, living in Galilee. Major characters, such as, Jehuda of Kerioth; Jehuda of Hamala; Barabbas, repeatedly invade the life of this silent land.

In "Dangaus ir žemės sūnūs" Krėvė employes a narrative style which is close to Biblical. Of particular effectiveness are extensive lofty dialogues which give an impression of a noble and solemn atmosphere to the themes. In general, it presents a panoramic picture of the religious and moral world of Jews in Christ's time.

V

It is notable fact that Krėvė drew materials from three diferent sources (rustic life, past of Lithuanian nation, Oriental and Biblical times) already at the onset of his literary activities. Oriental motifs, for instance, are employed already in the tale "Priešingos jėgos" (1907) and Biblical motifs in his life-long work "Dangaus ir žemės sūnūs" (1907-1954). Since the story "Bobulės vargai", written between 1904-5, describes a busy summer day of a simple, illiterate peasant Grandma, the legend "Gilšė", published in 1909, is based on folklore material of distant past of Lithuania. Similarly, throughout his entire literary life, Krėvė kept shifting back and forth from a narrow area of rural life to a wider domain of the nation's history, or to more universal sphere of the exotic Orient.

Despite his preoccupation with the three different areas, Krėvė's main center of concern was primarily man and his moral, spiritual and psychological complexities. Conflicts and problems of the most crucial periods of Lithuanian history are portrayed through actions, thoughts and agonies of major heroes, such as, Šarūnas, Skirgaila, Mindaugas. Agony and doom of Herod ("Dangaus ir žemės sūnūs") reflect another confrontation of two worlds, the Jews and Greeks. To portray a mode of simple, conservative rural life of the nineteenth century, Krėvė concentrated on several individuals, like Lapinas ("Skerdžius"), Gugis, Kukis, Grigas ("Raganius"), Vainoras ("Bedievis"), Kalvaitis ("Žentas"). It is characteristic that rulers, tragic and heroic individuals, suffer and perish as victims of their own inner dualism or dualistic situations; frequently duty comes before their personal life. The types of peasantry, equally strong-willed and resolute, are either the country sages (Gugis, Vainoras, Lapinas) or hard-working, shrewd heads of patriarchal families (Kukis, Grigas, Kalvaitis). although these and other individuals are men of flesh and blood and are of diverse and complicated personalities.

Diversity in themes, sources of inspiration and original characters resulted in a similar variety of genres and literary methods. Dealing with folklore and legendary heroes, Krėvė employes successfully a style of a romantic epic ("Dainavos padavimai"), while a genre of romantic chronicle play is used for depicting more dramatic and tragic events ("Šarūnas"). Since both tragedies "Skirgaila" and "Mindaugo mirtis" are l>asecl on historical persons, Krėvė applies a very effective style where both romantic and realistic aspects are fused in one dramatic unity. To create a peaceful, romantic, idealized picture of his own childhood village life, the same romantic -realistic method is used in short stories ("Raganius", "Skerdžius", "Bedievis"). When the subject matter extend through several centuries, such as in the mystery "Likimo keliais", Krėvė attempts to solve problems by application of various symbolic, mystical and allegorical devices. Dramatic lofty dialogues and partly Biblical style of "Dangaus ir žemės sūnūs" create an atmosphere of ancient times and seriousness of subject matter. Short stories, dealing with modern time ("Miglose", "Likimo žaismas") are written in a style of rather descriptive sketches or even in a manner of feuilleton. These mediocre stories and their semi-journalistic style make us wonder, whether Krėvė, being basically a late romanticist and dealing exclusively with historical, Biblical times and rural life of the nineteenth century, perceived modern life with social, political and spiritual complexities.

VI

However, Krėvė's greatness depends not merely on his choice and variety of genres, themes or use of various literary methods, but his mastery of them all. As a result, Krėvė's brilliant works of art signify his rare creative talent. In the realm of romantic and heroic epic, romantic and psychological drama and character delineation he has no rival in the annals of Lithuanian literature. In addition to this, he stands out as a master of literary language, which he successfully adapted to genres, themes and moods.

In spite of the fact that his

writings became

classics, Krėvė's direct influence on Lithuanian literature was

surprisingly insignificant. Apparently, there are no writers who can be

recognized as his pupils or who were considerably influenced by Krėvė's

works. However, his books were met with loud and invariable success;

throughout his entire life he was one of the most read writer, his

plays were staged and his works reprinted many time. His popularity, of

course, is due to the artistic values of his works as well as to his

idealization of ancient Lithuania and his promotion of national

romanticism.