Editor of this issue: Bronius Vaškelis

Copyright © 1967 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 13, No.3 -

Fall 1967

Editor of this issue: Bronius Vaškelis ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1967 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

CONTEMPORARY LITHUANIAN DRAMA

BRONIUS VAŠKELIS

Lafayette College

Bronius Vaškelis is Associate Professor and Head of the Languages Department at the Lafayette College, Easton, Pa. He holds a doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania. He is a specialist of Russian and Lithuanian literature.

The development of Lithuanian drama, which really started at the end of the nineteenth century, was interrupted by the advent of World War II and was deflected by it into two directions. Immediatly after the Soviet occupation of Lithuania in 1940, drama as well as other genres of literature were subjected to the narrow precepts of so-called socialist realism. At the same time a number of playwrights escaped the Soviet regime and developed under strong influences of Western culture, especially under the modern trends emanating from German, French, English and American drama. The different political and cultural milieu is res])onsible for the differences among the two currents of Lithuanian literature. Nevertheless, these differences should not be overemphasized and the works of both the expatriates and the playwrights within the country-are deeply rooted in Lithuanian culture and its dramatic traditions. It is necessary, therefore, to consider at least in an outline form the development of Lithuanian drama prior to 1940.

Drama Prior to 1940

The first Lithuanian play was staged in 1895 and marked the beginning of a demand for original plays and the consequent interest of writers to create them. Still there were only a small number of plays written during the first decade of the twentieth century. Most of these plays were incapable of sustaining interest and from a dramatic point of view they were lacking in originality. They did not differ much in ideas, motifs and sometimes even in techniques from other kinds of prose work. Aleksandras Fromas-Gužutis (1822-1900), considered to be an originator of Lithuanian drama, drew themes for his plays from several different sources: Lithuanian folklore and mythology, Lithuanian historical events of the 14th century and the contemporary life about him. These three sources have later been used successfully in the best Lithuanian dramas and tragedies.

Although several dramatic works of high literary merit appeared prior to World War I (for example Šarūnas by Vincas Krėvė, written in 1911), Lithuanian drama made greatest strides during the period of independence (1918-1940). The formation of professional theatrical group and the high-tened cultural awareness of the theater-going public encouraged the growth and maturing of the Lithuanian theater. Although poetry was considered the most successful genre, partly because of the large poetic output as compared to the scant number of plays written, nevertheless, in retrospect, it is possible to say that some dramatic works, especially those of Balys Sruoga (1896-1947) and Vincas Krėvė (1882-1954), are in no way inferior to the best poetry of that period.

The leading types of drama written during the

period of independence were comedies of manners and historical dramas.

The former was especially abundant since it enjoyed more popularity

among the audiences. Among those who mainly wrote comedies of manners

(K. Binkis, A. Rūkas, S. Laucius), Petras Vaičiūnas (1890-1959) was the

most active and prolific. Vaičiūnas wrote more than 20 dramatic works

which comprise the largest part of the original repertory of the

Lithuanian theater. His earlier works indicate strong tendencies toward

romanticism, symbolism and contain allegorical undertones. His later

works are of a more realistic nature, although they occasionally become

sentimental, melodramatic and didactic. His comedies are of a genial,

somewhat sentimental type, distinguished neither by wit or incisive

satire. Vaičiūnas usually satirizes the tirbanite as an egotist,

opportunist, hypocrite and idealizes the life of the peasant. From

contemporary perspective his plays appear to be of a narrow scope,

superficially dealing mainly with the problems of his time.

Historical plays, although fewer in number than comedies of manners,

were generally of greater aesthetic value. The two most important

writers of historical plays were Vincas Krėvė and Balys Sruoga. They

neither relied solely on the idealization of the historical or

legendary Lithuanian past nor did they seek especially to promote

national romanticism as other playwrights did; their concern was

primarily with man's feelings, passions, and inner conflicts.

V. Krėvė, a brilliant prose writer, earned his esteemed place in Lithuanian drama mainly because of his two masterpieces — Šarūnas (1911) and Skirgaila (1925) — written in the tradition of neo-romantic and psychological drama. His characters are distinctly delineated, full-blooded, tragic individuals. Krėvė focuses attention on their inner dramatic struggles rather than on overt actions or events. In Šarūnas, the protagonist, a man possessed by a reliellious and strong-willed spirit, disregards social and moral laws as well as old cherished traditions for the sake of national unity with which his own personal ambition is inextricably linked. Krėvė employs local color to create the impression of historical veracity. For example, he successfully incorporates folk songs and various ethnographical features. Skirgaila is a well-structured tragedy. Psychological, religious, and national conflicts are intertwined in the wrathful character of Skirgaila, the prince. Caught in the turmoil and throes of changing times, i. e. Christianity replacing paganism in Lithuania, Skirgaila, an astute and practical politician, is torn between personal ambitions and duty to his country.

B. Sruoga, famous also as a poet and a critic, was the most prominent playwright of independent Lithuania. To date, no contemporary Lithuanian playwright can seriously challenge Sruoga's esteemed position. His opus consists of more than ten dramatic works.

Since the subject matter of Sruoga's dramas is based on certain historical events in Lithuanian history, attention is focused on the epoch and the man within it. He chooses a critical moment in Lithuanian history, and through the feelings and struggles of several characters he reflects the spirit and ideas of the time. At first glance, it appears that the themes of his dramas are primarily concerned with sentimental patriotism or the promotion of national ideals. However, the ideas or theories of a nation are of temporal nature; like clothes they are changed and eventually wear out with the passing of time. What Sruoga aspires to is something of a permanent quality. Thus, he embodies in each of the protagonists of his dramas an awareness of the national spirit (or soul) existing in the Lithuanian people. Heroes die, but the spirit, although dormant in the younger generation, will again appear in the actions of national leaders. For example, in Kazimieras Sapiega (1947), the protagonist goes through a personal as well as a national defeat and emerges as an inspired, titanic individual, symbolizing the immortal soul of the nation.

The main characteristic of Sruoga is his ability to blend his theme with historical and lyrical aspects into one dramatic unity. In addition to this, Sruoga devotes a great deal of his attention to purely theatrical devices, such as scenery, setting, costumes, accoustical effects, and declamation.

Besides the comedies of manners and historical dramas written during the period of independence, a third minor category, somewhat related to the historical drama, may be mentioned. This category includes the mysteries and tragedies, written under strong neo-romantic and symbolic influences. The most prolific playwright in this area was Vydūnas-Vilius Storasta (1868-1953). His tragedies and mysteries, however, are really vehicles for the expression of his theosophical philosophy and are of minor aesthetic significance.

Drama Under the Soviets

Literature and culture in Lithuania were disrupted by the Soviet (1940-41) and German (1941-44) occupations. By the end of the Second World War (1944) Lithuania again was overrun by the Red Army; since then, all aspects of cultural and literary activities have been controlled by Moscow. Therefore, drama and other creative activities have undergone several changes and have acquired distinctly different characteristics from those which existed in independent Lithuania.

In 1946 A. Zhdanov, the Communist Party czar on culture. enunciated a new literary policy, the so-called theory of non-conflict. According to this theory deep conflicts no longer existed in socialist society. If a writer presented contemporary life negatively and included in his work contradictory emotional drives, tragic moments or clashes of interests, he was accused of "slandering Soviet life", dealing with "the non-typical for the Soviet man". Such a line in literature constituted in effect a death blow to dramatic literature and Lithuanian drama almost ceased to exist. A number of plays without conflicts and "comedies with a message" were manufactured. Such plays were simple journalistic tracts of propaganda, written in the dialogue form.

Between 1952 and 1956 the Zhdanov line in literature was modified and drama began to revive gradually. It was now acknowledged that some moral and social conflicts exist even in a socialist society. The writers were permitted greater freedom to experiment and to deal to some extent with negative aspects of Soviet life. Playwrights directed their efforts to portraying family and )>ersonal problems. Some of them attempted to deal in a satirical and comic manner with various defects and shortcomings of collective farms and their bureaucrats. Yet, despite a more refined treatment of problems, the playwright still had to work within a very narrow framework and his efforts usually produced only mediocre results. Among a dozen names in contemporary drama in Lithuania, only two, Juozas Grušas (1901) and Kazys Saja (1932), stand out as original and versatile playwrights.

Grušas established himself as a realist prose writer in the thirties and completed his first play. Father (Tėvas), just before the second Soviet occupation (1944). Well-drawn characters, vivid situations, and the use of effective theatrical techniques indicated Grušas' dramatic talent. However, for ten years he was silenced, apparently refusing to become a tool of propaganda or a "poster-like playwright". In 1957, in a brief autobiography, Grušas expressed his dramatic credo: "I would like in my dramatic works to create more distinct pictures of individuals who would lead stormy lives, who would struggle and overcome their obstacles, failures and inner contradictions',1 It is understandable that it was impossible for Grušas to realize his goals during the Stalin regime.

Even after Stalin's death Grušas' return to drama was not an easy one. Two plays, The Restless One (Nenuorama, 1955) and Smoke (Dūmai, 1956) have very little of the former Grušas; they barely can be distinguished from the other stereotyped and rhetorical plays of the "pre-thaw" period. However, in 1957, in the historical drama Herkus Mantas. Grušas definitely liberated himself from the stereotypes and banalities of socialist realism. Initially the play was criticized by orthodox critics, but now it is considered as the most outstanding drama of Grušas and the best play written in Lithuania under the Soviet regime. J. Lankutis, the leading drama critic in Lithuania, writes that "after having seen it, there is no desire to read and to see those plays which depict petty, small conflicts, where insignificant and ineffective problems are solved, where portraits of pale characters who joke poorly and who are primarily concerned with the commonplace are presented." 2

The plot of Herkus Mantas is based on a thirteenth-century Prussian uprising against the Teutonic Knights. Grušas focuses his attention particularly on inner religious and ideological conflicts of one of the Prussian leaders, Herkus Mantas. Born a Prussian and brought up in Germany, Mantas sought to free his nation from the slavery of the Teutonic Order and his pagan compatriots from superstition and ignorance. Having failed on both counts, Mantas, however, triumphs over a cruel, fanatical military-religious order of the Middle Ages through his invincible will to be free and to free others as well. The play's heroic and patriotic theme has many undertones. Emphasis is placed especially on national pride and the ideas of freedom. It is, therefore, understandable why the Lithuanians, ruled by the Soviets, fill up every seat at each performance. The drama is written in the tradition of neo-romantic tragedy, more specifically, in the tradition of Krėvė and Sruoga. It has a well-knit structure along with distinct, well-controlled compositional elements. Grušas has created outstanding drama, vividly delineating his characters, and flavoring his play with terse and expressive language.

Grušas' thesis-play Professor Markus Vidinas (Profesorius Markus Vidinas, 1963) deserves mention because of its well balanced, vigorous composition. The action in the play, however, is overshadowed by abstract concepts and intellectual discussions which tend to obscure the psychological and dramatic attributes of the play.

Grušas' recent plays, A Secret of Adam Bundsa (Adomo Bundzos paslaptis, 1966) and Love, Jazz and the Devil (Meilė, džiazas ir velnias, 1967), belong to the genre of psychological drama and the social and moral problem play. The plays are not structured in tight acts, but have loosely related scenes which shift from the present to the past. Undoubtedly, Grušas tried to adopt some compositional devices of contemporary psychological trends found in Western drama.

In The Secret of Adam Bundza, the main action takes place in Bundza's mind in the form of disputes between Bundza and his alter-ego, his conscience. The latter is per-sonified on stage. Dramatic tension reaches its climax when he is confronted by his illegitimate son, whose stepfather Bundza has betrayed during the Nazi occupation. The conclusion of the play makes it clear that no matter behind which mask oppressors are hidden, there is no justification for the betrayal of another human being or for compromising one's own convictions. Each person is responsible for his actions toward his fellow man as well as toward himself.

In 1967 Grušas' new tragicomedy Love, Jazz and the Devil appeared on the stage. It was immediately praised by audiences and drama critics as well. For instance, J. Lankutis writes:

A first impression stupefies you, and at once you realize that we don't have this kind of play. We feel as if we were jolted by a shock... As if the playwright tore off a dressing from some hidden wound and suddenly showed a life, where man, aware of his terrible emptiness, anxiety and anger, finds an escape in jazz, dance, vodka and rape.3

"The hidden wound" is nothing else than adolescent life in conteniĮjorary Lithuania. Instead of depicting another superficial, social or moral conflict, as do other playwrights in Lithuania, Grušas ventured to examine the reasons why youth is alienated from everything exept vodka, jazz, and sex. He wrote: "I want to find the very nature of passions, to discover where are these innate paths along which one goes from a beast to a human being or vice versa".4

The action of the play is constructed around the protagonist, Beatrice, a beautiful, good-natured girl, brought up by her grandmother. Her father abandoned the family a long time ago, and her mother stayed in Siberia with a lover. Beatrice often associates with three jazz players, with one of whom she is in love. She interprets their vulgar language, coarse behavior and contempt for everything, including love, justice, loyalty, decency, friendship as a whim of youth that will soon pass. She thinks that at heart they are still good and noble jieople. At the very end, having endured constant ridicule and suffered great insults, she suddenly comes to the realization of their beastly nature. In order to escape them, she jumps through the window of the fifth floor.

In Love, Jazs and the Devil attention is focused primarily upon the conflicts and actions of the three youthful protagonists Andrius, Julius and Lukas. They are similar in character and l)ehavior but differ in their social and family backgrounds. Andrius' father is an investigator for the Soviet secret police and an influencial man in society. Julius' father, who had been physically deafened by Andrius' father during an interrogation, has a doctor's degree in philosophy, which he received during the pre-Soviet times. At present, he is without a position and thoroughly despised by the Soviet regime. Lukas, a foundling, was brought up in a state boarding school. Different environmental conditions, however, have produced the same end results, i.e., the rejection of every humanistic tradition. For instance, "the ideals of humanism, of love, and of man's dignity have been trampled down, crushed, and knocked to pieces" by the Soviet ideology; the youths do not see any principles or ideals worthy to be followed. The youths have also rejected the Soviet ideology on the grounds that it is confusing, hypocritical, and baseless. In a dialogue which takes place between Andrius and his father, the investigator, Andrius justifies his scuffles with others, saying that

We (the younger generation) beat others only when we are angry... You (the older generation) have been beating each other according to a plan... then you had no time to be bored. You were conducting a class war... However, now you don't know what you have allowed to endure and what you have forbidden to exist, what you have eliminated (during the class war) and what you haven't eliminated.

The play is constructed basically on a principle of contrasts : a confrontation of sons and fathers, the injustice of the "cult of personality" and the personal guilt of the admirers of the "cult", love and animal lust, human compassion and cruelty. However, Grusas managed to blend them into one powerful tragic synthesis. He presents his audience with a dramatic vision of futility and an awareness of shocking reality. From a dramatic point of view, unfortunately, Grusas' Love, Jazz and the Devil as well as The Secret of Adam Bundza are marred by occasional relapses into melodrama and especially into moralizing in the manner of a stereotyped play.

Among a group of younger playwrights, Kazys Saja is the most prolific. He has gradually proven himself to be a talented author. He started his career as a writer of comical stories and of gay, mediocre social comedies. His comedies, nevertheless, attracted the attention of the audience and critics. For example, his comedy Seven Skins of a Goat (Septynios ožkenos, 1957) dealt with peasant life on a collective farm. It was at first censored because the critics saw it as a "distortion of Soviet reality". To prove his point that peasants lead a life of semi-slavery and are half-starved and clothed in rags and cheated by the farm bureaucrats, Saja actually brought the peasants before the censors. It is not known whether this unusual act of "testimony" helped. However, when this comedy was staged at last, the audience was amused apparently not by its dramatic qualities, but by seeing ills and follies of collective farms being exposed and ridiculed for the first time on the stage.

The first significant dramatic work of Saja is his psychological play, The First Drama (Pirmoji drama, 1962). It depicts the gradual downfall of an artist who is henpecked by his wife, despised by the director of the school where he works, and misunderstood by the people around him. The play makes fun of those who, instead of lending a helping hand, accuse, judge, and preach. However, it lacks a dramatic tension and a balance of structural elements.

Another aspect of Saja's probing into contemporary problems is presented in the play Anxiety (Nerimas, 1963). Its plot is simple: when a high school student becomes disgusted with his bureaucratic and influential communist father, with his twist-and-vodka-loving classmates, and with social hypocrisy in general, he decides to become a simple but honest factory worker. Saja was the first one who dared to dramatize in a critical manner the old father and son conflict in Soviet society. The play's popularity rests, however, more on controversial subject matter rather than on dramatic value.

In the play Sun and the Post (Saule ir stulpas, 1965), Saja turns to a moral problem. Focusing on tension caused by guilt he constructs an intricate plot. A physician kills a drunkard in a car accident. On the basis of circumstantial evidence, "an innocent man is accused and convicted for the accident. Later it becomes clear that the physician's recklessness was due to his disturbed state of mind, prompted by the discovery of his wife's love affairs with a police inspector. This same inspector later conducts the investigation of the accident. The physician confesses, but Saja leaves the question of guilt unanswered.

In his trilogy, consisting of three one-act plays, The Orator, The Maniac, Prophet Jona (Oratorius, Maniakas, Pranašas Jona, 1966), Saja made a new step toward implementing the techniques used in modern theater. This experimental play is the first of its kind in the Soviet Union. In certain respects, it follows plays of contemporary Czech and Polish playwrights, especially S. Mrorzek. Saja deals exclusively with ideas, feelings, and basic foibles of man, i.e. fear, betrayal, servility, greediness. He treats them on an allegorical and symbolic level. The trilogy is a grotesque, ironic, and satirical portrait of iieople. For instance, in The Orator, apartment tenants have become so servile and obedient that, out of their fear of authority, they are even afraid to speak to their 'commandant", a superintendent of the apartment. (Saja apparently uses the term "commandant" in a figurative sense.) Having sunk to the level of foolish children, they live on the false hope that the "orator", who actually has lost all sense of reality, will speak on their behalf. In The Maniac, passengers on the train susjiect each other of being a fugitive from a psychiatric hospital and inform on each other. Meanwhile, the train, operated by a mental patient, rushes forward with unusual speed. Finally, the passengers realize that the mental patient and his henchmen have taken control of the train, and the passengers see no other alternative than to obey them. In Prophet Jona, during a storm at sea, certain passengers throw women and weak men overboard in order to lighten the load. Later, they rapaciously divide amongst themselves the belongings of the victims. Blinded bv the fear of death and their instinct for self-preservation, they even toss the innocent prophet Jona into the waves. Ironically, without his guidance they now will not be able to reach the shore.

The theme of the trilogy is based on the follies of man in general, but specifically alludes to particular social ills of the present. For example, the maniac and his fanatic followers who happen to "have more rights than wisdom" could be analogous to situations which existed under the leader ship of Hitler, Stalin, or other dictators. Those who experienced the terror and repression of Hitler or Stalin find nothing different in the behavior of their biblical counterparts in Pro-plict Jona or in the behavior of the speechless tenants in The Orator: "As it has been before, so it will be in the future. What you have done in the past, you will do again. There is nothing new in this world".

The Soviet literary press recently reported that a new grotesque play by Saja, entitled Hunt for Mammoths (Mamutij incdsioklc), had been rehearsed. However, until now, the play has neither been allowed to be staged nor published. Its plot is simple. People are in search of a festival which supposedly is taking place beyond an immense swamp. Along the way, they meet with people from the other side of the swamp who are looking for the same festival. The leaders who have lured the people by promises and persuasion into a wild goose chase manage to flee. Realizing that the festival is nothing but an illusion, the people decide that they will, nevertheless, hold a feast, although they are half-sunk in the middle of the swamp. Some have suggested that the censors saw in the play a parody on Communism.

Works of other contemporary playwrights (J. Miliūnas. A. Gricius, V. Rimkevičius. D. Urnevičiūtė) are considerably inferior to those of Grušas and Saja. Critics in Lithuania, like A. Masionis, admit that playwrights

are unable to free themselves from presenting petty problems of the day in a pictorial, poster-like manner... There is little understanding of dramatic effects and analysis, but a lot of detailed, artificial situations.5

Another critic. G. Mareckaitė, recently wrote that

Our playwrights also do not dare to deal with certain problems and conflicts... Often one thinks that a real drama or tragedy is nothing else than an obstacle to the theory of optimism and progress... Everybody throughout the Soviet Union is looking with candle for a good play. Having found an average contemporary play, everybody wants to have it.6

Lithuanian Drama in the West

Some Lithuanian playwrights fled their country to escape the second Soviet occupation (1944), and after a short sojourn in displaced persons camps settled in several centers of the Lithuanian diaspora, the main one being the United States. At first they had to overcome the hardships of adjusting to new situations and often had to learn new skills and professions. Moreover, there was no professional theater; there exsisted at most a few amateur groups which were formed for the purpose of staging one or several plays.

Despite unfavorable conditions, Lithuanian drama in exile managed to survive. For several years after the war, there were only a few dramatic works and these were not of great value. By the fifties plays of higher quality began to appear. The majority of the authors were newcomers.

Playwrights living in the West may be grouped into the traditionalists and modernists. Among the playwrights belonging to the first group who already started their literary career in Lithuania are S. Laucius (1897-1965), A. Rūkas (1907-1967), and V. Alantas (1902). As is characteristic of most political emigrants, they held on dearly to the traditions of their former lives in Lithuania and sought in their works to give dramatic form to their reveries, reminiscences and sorrows. The literary and spiritual life of their new land exercised no apparent influence on them. They usually dwelled on social and moral problems or attempted to describe the heroic resistance of the Lithuanian underground; only a few plays were concerned with current problems of emigrants. From a dramatic and structural standpoint, their plays continued exploiting the conventional techniques of Vaičiūnas and were rather dull imitations.

Two additional traditionalists, Jonas Grinius (1902) and Anatolijus Kairys (1914), produced their first dramatic works while in the West. Grinius' play The Rat-Cell (Žiurkių kamera, 1954), based on events in a Soviet prison, and an historical play, Song of the Swan (Gulbės giesmė, 1950), whose action takes place in 16th century Lithuania, both exhibit the author's attempt to follow the pattern of the classical drama and to instil lofty national and moral ideals into rather static, superficial characters. Heroic themes and various confrontations were poorly developed. A. Kairys labored primarily in the realm of satirical comedy and slowly gaineu popularity, especially among the older compatriots. His success was due to the fact that he proved to be more a gifted psychologist than a dramatist; he appeals to the sentiment of his uprooted compatriots with themes such as patriotism, national pride and loyalty, and the need to preserve the Lithuanian language. In general, A. Kairys' plays, The Tree of Freedom (Laisvės medis, 1955), Diagnosis (Diagnosė, 1956), Chicken Farm (Viščiukų ūkis, 1961), Curriculum Vitae (1967), filled with numerous symbols and pale aphorisms, have usually a form of naive, artless allegory.

Whereas the above playwrights adhered mostly to the traditions of independent Lithuanian drama, the so-called modernist playwrights, i.e. Antanas Škėma (1911-1961), Algirdas Landsbergis (1924), and Kostas Ostrauskas (1926), have definitely been influenced by modern literary currents. Nevertheless, they neither divorced themselves from the literary and cultural heritage of their native country nor ignored the problems of emigrants. On the contrary, their experiences abroad and the influence of the Western drama enabled them to deal more profoundly with the fate of enslaved, exiled; or alienated man.

A. Škėma belongs to that generation of writers who reached maturity in their native land but produced most of their works abroad. However, at the pinnacle of his career, he died in an auto accident. He left behind four published plays together with various works in prose. His dramatic works are: Živilė (1948), The Awakening (Prisikėlimas, 1956), The Candlestick (Žvakidė, 1957), A Christmas Skit (Kalėdų vaizdelis, 1961). Several unpublished manuscripts of dramatic works are also extant.

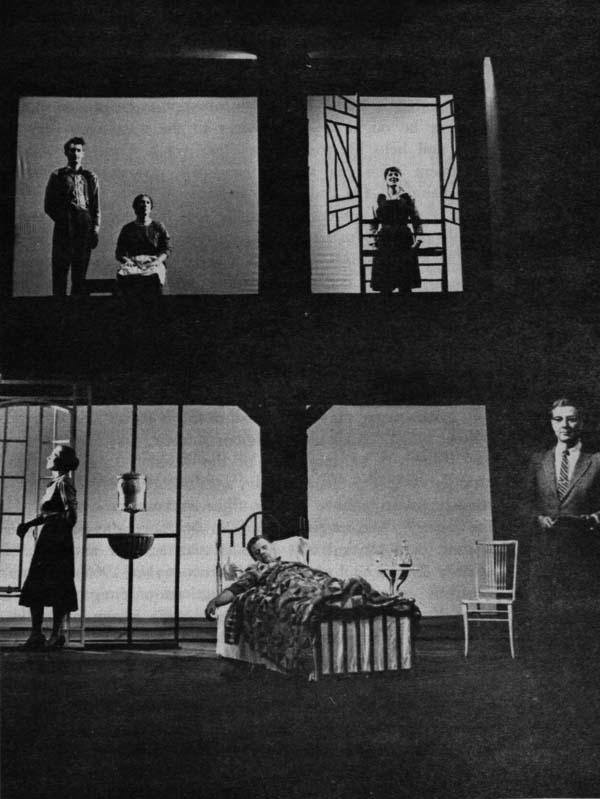

A scene from the production of Živilė (A. Škėma)

by the Chicago Lithuanian theater.

One of Škėma's more obvious characteristics as a playwright is that he had what might be called an ear for action and a gift for orchestration of various, sometimes hardly compatible, theatrical effects and tricks. Each play is marked by sharp intrigue and an inner tension which is enforced by dramatic situations and daring, unexpected confrontations. At times it appears as though he intentionally seeks to shock the audiences by means of vulgar phrases, naturalistic passages, profane images, and the like. In general, his earlier experiences in the theater as an actor and later as a director deepened his awareness of dramaturgy.

From a structural point of view, the dramatic tension in Škėma's plays develops within a triad of conflicting elements. In Živilė and in The Awakening, for example, two men, opposing each other from different political positions, are in love with the same woman. In The Candlestick he employs Adam's, Abel's, and Cain's reciprocal relationship with each other to depict the father and son confrontation. Since Škėma focused attention on the psychology of his characters and especially on the presentation and analysis of ideas, he apparently did not try to construct an intricate web of conflicts. As far as themes are concerned, however, Škėma returned repeatedly to one main idea, i. e. betrayal and loyalty. Yet each time it is examined by him from a different point of view, of time and of place. In Živilė one notes the idea of man's effort to gain freedom and love at the expense of betraying his own country. The action takes place during three crucial moments in Lithuanian history — the Middle Ages, the nineteenth century and the Soviet occupation. In each instance oppressors and quislings triumph over those who have refused to compromise or betray their own convictions. In The Awakening, the confrontation takes place in the prison of the NKVD between the Soviet secret police investigator Pijus and the rival of his student days, Kazys. At present, Kazys is a member of the underground resistance. Pijus attempts to force Kazys to betray secrets of the resistance by torturing Elena, Kazys' wife, the woman with whom both Pijus and Kazys are in love. Finally, Pijus shoots Kazys in a moment of pity without ever having learned his secret. However, as the victor, Pijus soon realizes that it is a Pyrrhic victory. By sheer force he fails to conquer Kazys' determined will to resist and his belief in the ideal of freedom.

In The Candlestick

the betrayal motif is viewed from a different angle. The scene is set

in Lithuania in 1941. During the last few days of the first Soviet

occupation, i.e. just before the German attack, the protagonist Kostas,

who works for the Soviets, betrays his uncle and kills his own brother.

Kostas had betrayed in accord with his convictions; he killed his

brother because he had felt contempt and jealousy since his childhood.

By killing Kostas frees himself from his frustrations. When he knows,

however, that he soon has to face death, he begins to doubt his

convictions. Nevertheless, he ultimately approves of his actions and

the logic of his choice. He made the choice himself and executed it

voluntarily; he alone is responsible for it. It is obvious that

Škėma was influenced by Sartre's idea of free action of the

individual and used it as a means to probe the secrets of the human

mind.

Despite the well developed intrigue and skillfully incorporated

structural and theatrical elements in the play, Kostas' inner conflicts

lack depth and clarity. The Candlestick,

therefore, is interesting as an experiment in which ideas of

contemporary philosophy and psychoanalysis are tested in dramatic

situations. However, Škėma was much more successful when he

relied more on interesting psychological situations. This is

demonstrated in his one-act play, A Christmas Skit,

in which the characters, mental patients, are acting for therapeutic

purposes. No longer there are villains, who represent an oppressive

force, nor heroes struggling for their convictions. All are sufferers,

and through their own reminiscences and psychological probing they hope

to find a way out. A Christmas Skit

has a well developed plot. Striking contrasts and psychologically

plausible differences and the inner perplexities of the characters make

this a forceful play. The surprise ending is indeed well handled. In

some respect A Christmas Skit resembles Marat/Sade of Peter Weiss, although Škėma wrote it a few years earlier.

Algirdas Landsbergis appears closer to the spirit and techniques of

modern Western drama than Škėma, although his subject matter

also is drawn from Lithuania or its emigrants. The staging of his first

play Five Posts in a Market Place (Penki stulpai turgaus aikštėje,

1957) caused a controversy among the Lithuanian emigrants. Those

accustomed to patriotic and conventional melodramas accused Landsbergis

of degrading post-war Lithuanian resistance to sovietization. However,

Landsbergis attempted to analyze the last hours of several of the

partisans from a human rather than an heroic point of view. Following

seven years of bitter and fearless struggle, the oppressors have

annihilated most of the partisans. Antanas, leader of the last attempt

at resistance, doubts whether he ought to die fighting to the last

breath or stay alive and help his country in other ways. Confronted in

an apartment with his arch enemy, the prosecutor, who has been hanging

the bodies of partisans on posts in the market place, Antanas wavers

and finally lets him go. He is unable to kill an individual, even the

prosecutor who appears as miserable and hopeless as he. However, both

Antanas and the prosecutor are killed in a shooting which subsequently

takes place.

A scene from the 1961 production of The Five Posts (A. Landsbergis)

by the Gate Theater, New York.

Despite the structural imperfections and occasional digressions into the realm of intellectualism, Landsbergis has succeeded in conveying a tragic and powerful vision of dehumanizing and demoralizing forces on both sides.

Landsbergis' play The Wind in the Willows (Vėjas gluosniuose, 1958), based on a religious miracle, resembles in form and content a mystery play of the Middle Ages. The play lacks unity in the theme and an adequate plot. Nevertheless, a comprehensive picture of the fifteenth century emerges. On the whole, Landsbergis appears to be more successful when writing in a comical and satirical manner. For example, his comedy The School of Love (Meilės mokykla, 1965), assembled from various episodes and situations of emigrant life in New York, conveys a twofold, grotesque image of reality: an external reality consisting of flashes, noise, and speed, and an inner or subconscious reality hiding man's secret desires, his day-dreams and aspirations.

Landsbergis reflects this motif by means of his protagonist, Bangžuvėnas, a former store keeper in Lithuania. At present, Bangžuvėnas has taken up the more unsavory profession of confidence man and has founded a school for love. At last his unbridled imagination forces him to run for emperor. The secondary characters, all of Lithuanian descent, are highly individualized and function in helping Bangžuvėnas' dreams and desires to materialize. By means of parable and allegory, Landsbergis manages to integrate fantastic, hyperbolic characters and their grandiose dreams within a kaleidoscopic setting adopted from the world of radio, TV, films, and advertisements. In general, it is a powerful grotesque comedy of manners. Several trivial farcical episodes and an occasional muddle of structural elements do not destroy the sense of unity of the play.

The play The Beard (Barzda, 1967) is written in the vein of a farcical comedy. An individual, Everyboy, tries to defend his convictions and rights to be individualistic and independent. His parents want to steer him to a profitable profession ; political leaders hope to bring him up as a "yes-man". There are many farcical and grotesque situations, some of which resemble separate episodes loosely bound to each other. As a whole Landsbergis relies too much on suggestive power of theatrical tricks than on intrigue or characterization.

A short, one-act play, Farewell, My King (Sudie, karaliau, 1967), described by Landsbergis as a poetic melodrama, depicts an old actor whose spirit has been broken and who lives on moments of former glory. On stage, playing a role of King David, the actor regains his strength and even manages to enthral a young actress who is playing the role of a slave.

Kostas Ostrauskas is regarded as the playwright who, in his play The Pipe (Pypkė, 1951), introduced into the Lithuanian drama various techniques of the theater of the imagination. Later, to some extent, the so-called theater of absurd is reflected in his play Once Upon a Time There Was an Old Man and an Old Woman... (Gyveno kartq senelis ir senele..., 1963).

The one-act play The Pipe

is commendable for its originality in the treatment of subject matter

and style. Following a murder the killer "Z" and his victim "A"

recreate the process which led to the murder. "A" buys an old tobacco

pipe which is believed by "Z" to contain a hidden diamond. After having

killed "A", "Z" realizes that it was the wrong pipe. The actions are

intensified by the pipe which is depicted as a third character. In a

female voice it participates in the play, addressing the audience

either as a clairvoyant protagonist or as a sneering commentator.

The Pipe exhibits the main features of Ostrauskas' dramatic vision and style, developed more extensively in his later plays. Dialogues are very short, consisting usually of a few laconic phrases. At first glance it appears to be a fantastic play with comical undertones, but beyond this facade there appears to be a hidden sad and tragic moment. Furthermore, Ostrauskas incorporates many thematic and theatrical elements by means of riddles, allusions and symbols. Therefore, the reader or audience has ample opportunity to interpret them subjectively.

The play A Little Canary (Kanarėlė, 1956) is written more in keeping with the traditional theater. Its theme and actions are developed along a twofold plan. On the one han (į everything is placed against the naturalistic background. Beg-gers in rags squabble in their vernacular lingo for a stewed potato or a sip of vodka. On the other, namely the symbolic level, a simple canary becomes a symbol of eternal beauty. Beggars represent not material misery, but rather are spiritual victims, crushed by various injustices. The play's somber setting is brightened by lyrical undertones and by witty and humorous situations. In general, it is a dramatic and uplifting vision of the unheroic characters' spiritual world.

In the one-act play entitled In the Green Meadow (Žaliojoj lankelėj, 1961) Ostrauskas focuses his attention on two main characters. A helpless, tragic man, named Homeless, is terrorized and killed unintentionally by a brutal tavern keeper. The latter is vividly delineated with vigor and distinct traits, while the former, being a passive and unimpressive opponent, is depicted in a flimsy manner. The accidental death of the innocent victim, Homeless, is used as a means to expose the tavern keeper's insecurity and misery which he has tried to disguise by braggadocio and attacks on innocent people. Since actions are based primarily on dialogue, various secondary devices, such as acoustical effects, lights, silences, enigmatic persons, etc. are used for the purpose of reinforcing the tension and intrigue by means of suggestive and symbolic connotations. However, the numerous symbols of dark fate which inevitably forbode the approaching death of Homeless do not produce an adequate tension and illusion of the menacing fatal moment. The plav appears to lack cohesion and balance.

The play Once Upon a Time There Was an Old Man and an Old Woman... differs from previous Ostrauskas plays in several respects. The plot is based on a nonsensical subject matter. The Old Man's and Old Woman's son died several years ago in an automobile accident. Since then they rent a room to a youth resembling their son. After having rejoiced with him, they kill him. In the play they go through the process of preparing and killing the eleventh victim, the student. Beside the depiction of absurd situations of the private life of the old couple, Ostrauskas effectively incorporates similarly absurd items prevalent in public life, which are read aloud from newspapers by the old couple. Since for the old couple the act of killing has become a meaningless game, newspaper items, such as those treating political chaos in the world or politicians and their views on the atom bomb, all appear to be devoid of meaning, a hollow play with words. The structural elements and effects of the play are functional and expressive, especially the authentic quotations from the press, rhythmical laments from Lithuanian folklore, conversions of words into sound effects. Portions of C. Gluck's Orpheus and Euridice are used as background music to emphasize the irony of a situation or to point up contrasts of action in the play.

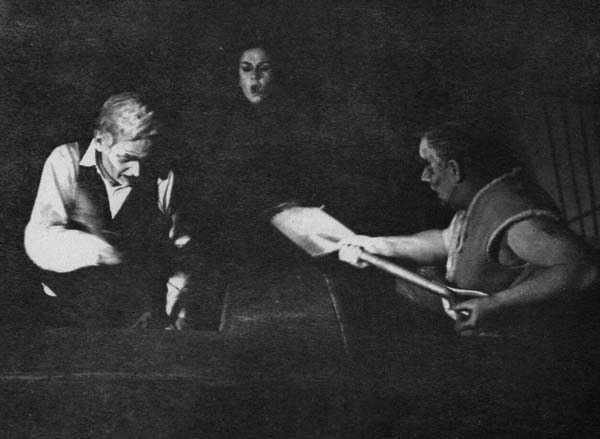

A scene from the 1967 production of The Gravediggers (K. Ostrauskas)

by the Chicago Lithuanian theater.

In three out of four Ostrauskas' plays, death appears as a consequence of an act of brutal force, although always unintentional or irrational. Death is inflicted upon a passive, innocent victim or it resembles the situation of the wolf and the lamb. In his recent one-act play, The Gravediggers (Duobkasiai, 1966), Ostrauskas probes into the secret of death. The plot is very simple. Two men, a peasant and an actor, are digging a grave in the cemetery. A young female appears. Within a few minutes time, she forces them into the grave and buries them. Here again as in the previous plays one sees repeated the same lamb and wolf situation. Two gravediggers are innocent victims, while death in the figure of the young woman represents the brutal force. She (death) is victorious. The irony and absurdity of the whole situation is that she is even more unhappy than the victor in The Pipe or in In the Green Meadow: "I'm tired... O God! Where is my own old age. Where is my death?" she cries. Does this statement confirm nihilistic absurdity (i. e. death itself, as well as man's life, is nothing but a nonsensical and meaningless state of being), or does it, on the contrary, affirm that no matter how senseless or absurd man's life would appear, it is still much better than an endless, empty existence?

The structure of the play is condensed into a bare minimum. Dialogues are laconic and each phrase is charged with evocative and suggestive power. Quotations taken from Hamlet add new dimensions to the development of the theme. The structural elements and various theatrical effects are few, flexible and equivocal. In general, from the structural standpoint, The Gravediggers resembles a skeleton with images and symbols. Only under the guidance of a creative director could the play appear on stage in its fullest vitality and brilliance.

________________

Contemporary Lithuanian drama abroad as well as in

Lithuania did not develop completely separately. Despite differences in

choice of themes and their treatment, both branches of drama are bound

together by the same cultural and literary traditions. Lithuanian

playwrights abroad, adopting certain aspects from the contemporary

Western drama, continue to deal with themes and problems of life in

Lithuania and in the lives of the Lithuanian emigrants. Because the

theory of socialist realism and other external controls have hindered

experimentation, playwrights in Lithuania during the past decades have

had to rely primarily on various traditions prevalent within

independent Lithuania. The drama of Soviet Russia, having so little to

offer because it is based on the traditions of the 19th century Russian

school of manners, is hardly an ideal which Lithuanian playwrights

would care to emulate. When more freedom for experimentation was

allowed, the playwrights in Lithuania turned to the West for new ideas

and new dramatic techniques. As one may see from recent innovations in

several contemporary plays in Lithuania, the playwrights tend to follow

a similar pattern, one which was initiated by their expatriates about

10-15 years ago. By their innovations, such as the exploitation of the

drama for the purpose of gaining greater psychological insight, they

have not only helped to rejuvenate Lithuanian drama, but shown

themselves to be veritable artists.