Editor of this issue: Anatole C. Matulis

Copyright © 1968 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 14, No.1 -

Spring 1968

Editor of this issue: Anatole C. Matulis ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1968 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF THE

DECLARATION OF LITHUANIA'S INDEPENDENCE

Recollections of a Participant

DR. JUOZAS PAJAUJIS

In commemorating this year the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of

Independence of Lithuania, it behooves to recall the events which had

led to this action, to recall the very first 16th of February in

Vilnius and the developments immediately thereafter. I resided in

Vilnius at the time and took an active part in the events. It is true

that I was fairly young at the time, having belatedly — due

to the hostilities of war — passed the high school

examinations, and my part was but secondary, of course. I was employed

at the time on the editorial staff of "Lietuvos Aidas" — "The

Echo of Lithuania", the Lithuanian language newspaper published by the

Council of Lithuania. I was the secretary of the editorial staff, in

charge of relations with the German military censor's office, and it

was my job to submit to the censors the text of the February 16th Act.

The actual editor was Petras Klimas, member of the Council, the

"Taryba".

Developments of World War I created favorable external circumstances for action. The Russians had been pushed far to the east. The Germans occupied Lithuania in 1915 and did not feel quite at home in this country. What was to be done with the occupied Eastern areas after anticipated German victory? There was no unanimity among the Germans with regard to the policy on this question. Some members of the Reichstag, the Parliament, associated with democratic parties, like the Social Democrats (Scheidemann, David) and the Catholic Zen-trum (Groeber, Erzberger), were amenable to letting the areas liberated from Russia have self-government. Particularly friendly to Lithuanians and very active in their behalf was Mathias Erzberger. On the other hand, German nationalists and the so-called "war party", especially the top echelon of the German military government in Lithuania, frankly and determinedly championed annexationist designs. The official ruling circles in Berlin were looking for diplomatic means to cover the annexationist designs with the alleged will of the population — at least by exacting collaboration of the leading personalities. With this in mind, an attempt was made to create a certain advisory organ associated with the German military government, a so-called "Council of Trustees", a "Vertrauensrat". The Germans had approached Bishop Karevičius and dr. Basanavičius and other prominent Lithuanians, yet no Lithuanian agreed to become a member of such a subservient Council.

Eventually the need for having an organized Lithuanian representation sharpened and acquired urgency, as a perspective of a separate peace with Russia loomed after the Russian revolation. It was deemed advantageous to possess during the peace negotiations some legitimate decisions by representative organs of the occupied areas to separate and secede from Russia. Therefore, in the fall of 1917, the German military authorities reluctantly allowed the Lithuanians to call a conference in Vilnius (September 18-22), which elected a twenty - member Council of Lithuania (Lietuvos Taryba). Of course, the Germans continued to nurse their designs to convert the Taryba into its subservient advisory body. However, the members of the Taryba, guided by the decisions of the Vilnius Conference, considered their main and specific task to proclaim the restitution of a Lithuanian State prior to a general peace conference, and to secure the recognition of that State by Germany in the first place.

The road lying ahead of the Taryba was pitted with many pitfalls. To divorce Lithuania from Russia — yes, this was agreeable to Germany. But to let Lithuania slip from the German stranglehold — never. Therefore, the Taryba had to maneuver with skill.

It was clear that no support could be expected not only from the Kaiser's government, but from the friendly Reichstag circles, unless some concessions be promised by the Lithuanians regarding their future relations with Germany. Taryba members were also influenced in this conciliatory reasoning by their realization of the hard fact that the Western Entente powers showed no interest whatsoever in the problem of Lithuania.

Dr. Juozas Purickis, who participated in the Vilnius Conference as the observer from Switzerland, confidentially pointed out that the Western Allies were preoccupied with their own worries, particularly because of the disruption of the Eastern Front by the revolution in Russia. Therefore, no concrete support could be counted on in their efforts to make the cause of Lithuania into an international problem. The British and French press printed some scant accounts of the events in Lithuania, yet viewed the events as alleged German machinations rather than the true aspirations of the Lithuanians. Even the formation of the Council of Lithuania was viewed in that light. No concrete help could be expected during the war years from United States of America, regardless of the strenuous efforts exerted by Lithuanian Americans. America was primarily concerned with winning the war and carefully shunned anything that might possibly hurt its great ally, the interests of "one and indivisible Russia", as was later amply demonstrated by Secretary of State Lansing's policy at the Versailles peace conference. No good could be expected by the Lithuanians from the post-revolutionary Russian regimes, be they led by Lvov or Ke-rensky or the rapidly rising Bolsheviks — to whom the principle of national self-determination meant but a theoretic right to submit to the dictatorship of the Russian communist party.

Due to these various factors, Taryba's relations with the Germans were in a flux and oscillated like a pendulum according to barometric indication of the German successes or failures at the war fronts, and reflecting the strengthening or the weakening of the war party in the government of Berlin.

One positive development was the success after many efforts, at gaining an audience for the Taryba Presidium with Reichskanzler Hertling in Berlin on December 1, 1917. A preliminary agreement was initialed in the form of a protocol which projected a formula for declaration of Lithuania's independence, yet inescapably bound such a declaration with a clause for an "eternal and firm association tie" with Germany by negotiating four conventions: the military, communications, customs tariffs and monetary. This protocol provided the base for the so-called Declaration of December 11, 1917.

The question of conventions with Germany led to a split in the Taryba. When the peace negotiations with the Bolshevik govenment of Russia at Brest Litovsk were resumed after an extended recess or break, the Germans demanded that Taryba accept the entire text of the December 11th declaration, but that only its first part, declaring Lithuania's secession from Russia, be communicated at Brest Litovsk. When the problem of this notification came to a vote in the Taryba on January 26, 1918, only eight members voting against, four resigned from the Council (Biržiška, Kairys, Narutavičius, Vileišis), and the other four opposing members remained in the Council (Stulginskis, Staugaitis, Smilgevičius, Vailokaitis).

The split vote was not deemed

acceptable to the Germans and the delegation of the Taryba failed to

get a permission to go to Brest Litovsk. Meanwhile the peace

negotiations broke off, and the problem of Lithuania again lost its

urgency in German affairs.

International negotiations among the Taryba members and with the former

members continued throughout the first two weeks of February. The four

oppositionists had submitted earlier their statement to the Taryba

majority, including a declaration of independence omitting any

reference to special ties with Germany. Should the majority accept

their formula, they would return to Taryba.

The differences in views of the majority and the opposition could be

defined as a conflict of two different reasonings. On the one hand

there were the so-called realists, or more properly opportunists, who

were inclined to defer to the moment's circumstances and to placate the

occupying power. On the other side were strongly principled men who

refused to bow to circumstances and would make no unacceptable

compromises. Soon enough the Taryba majority became likewise convinced

that before the end of the war a declaration of Lithuania's

independence could not be made without a conflict with the occupational

authorities. This realization was the decisive motive which bound the

Taryba to decide on February 15th, after prolonged mutual negotiations,

to accept the formula proposed by the opposition, with inconsequential

editorial changes — the formula originally drawn by Steponas

Kairys and now edited by Petras Klimas. This formula was finally

accepted by all members of the Taryba on February 16th, 1918. The

formula is translated as follows:

|

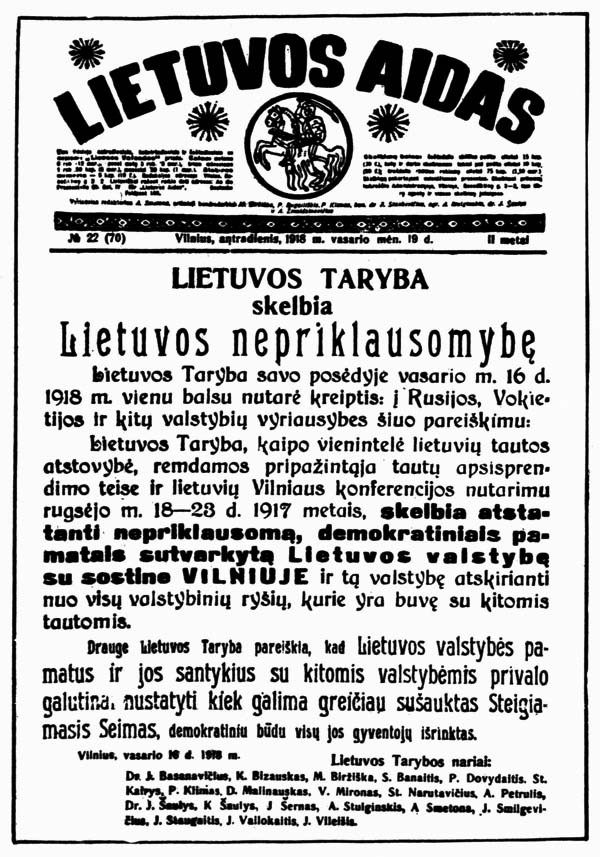

| The title page of Lietuvos Aidas,

the Lithuanian newspaper in Vilnius, announcing the declaration of

independence. For the circumstances of its publication, see the memoirs

of Dr. J. Pajaujis, published in this issue. The declaration is

translated on page 9 [below].. |

The Lithuanian Taryba, in its session of February 16, 1918, decided unanimously to address the following communication to the governments of Russia, Germany, and other states:

The Lithuanian Taryba, as a sole representative of the Lithuanian nation, on the basis of the recognized right of self-determination of nations and of the decision of the Lithuanian Conference of Vilnius, September 18-23, 1917, proclaims the reestablish-ment of an independent, democratically organized Lithuanian state, with Vilnius as capital, and the abolition of all political ties which have existed with other nations.

At the same time the Lithuanian Taryba declares that the foundations of the Lithuanian state and its relations with other states must be finally determined by a Constituent Assembly, to be convoked as soon as possible and elected democratically by all the inhabitants.

Vilnius, February 16, 1918

It was a magnificent scene when all twenty members of the Council gathered in the modest premises of the Lithuanian Committee for the Relief of War Sufferers at No. 2 Grand (Didžioji) Street in Vilnius. Dr. Jonas Basanavičius read the text, and the Declaration of the Restoration of Lithuania's Independence was adopted unanimously and signed to by all members.

However, it was one thing to adopt a declaration within the Taryba's membership, and it was quite a different thing to proclaim it "urbi et orbi", to make it known inside Lithuania and to the world at large. It was obvious that the document had to be published in the very next issue of the "Lietuvos Aidas". Nevertheless it was equally obvious that a revolutionary declaration enacted against the will of the military occupying government of the land, woud not be allowed by the military censorshop to be printed in a newspaper. There were optimists, like dr. Jurgis Šaulys, who reasoned that the censor's office "would not dare" to delete a document of such importance and, in fact, he handed the text that same evening to Herr Bonin, the representative of the Geman Foreign Office in Vilnius.

We at the editorial office headed by Petras Klimas were well aware of the censors' mentality. We had ample experience with the consorship office. For instance, whenever the censor encountered in any article the expression "independent Lithuania" — in translation: "Unabhaengiges Litauen", and everything had to be submitted in German translation, — he systematically crossed out the word "unabhaengiges" and would write in "selbstaendi-ges", or selfgoverning. The editor at all times had to deal with another problem. The permission to publish the newspaper was granted by the Germans on condition that it would contain no blank spaces and that the newspaper be published regularly whenever less than one third of the text was penciled out or the publisher pay a 10,000 Mark fine. For this reason we had on hand a sizeable reserve of articles already approved by the censors in order to fill in blank spaces left by the censor's pencil. On the present occasion we had to strive in the opposite direction: we decided to set in type an issue that could not possibly be allowed by the censor — that more than one third of the text should be crossed out and the issue would not appear, yet would not draw the large fine. As long as we were not able to publish to Declaration of Independence, we did not want to come out with a regular issue as if nothing had happened.

February 16th that year was Saturday. The newspaper was due to come out Monday, and consequently we had enough time. The Declaration of Independence was set in type in large letters taking up the entire page one. To fill other pages we gave to typesetters a number of articles pulled from our desk drawers — articles of strictly censorable contents and correspondent reports from the provinces about the brutal requisitions, the depletion of timber forests, and the like. And I wrote a supplementary article — under a nom de guerre — about the Lithuanian struggle against the Teutonic Knights.

When the newspaper of this sort was set in type, I picked up proof sheets and around 10 p. m. arrived at the censor's office at the Deutsche Pressestelle. My visits there usually lasted from a half hour to one hour in the waiting room. That evening, however, I waited there about three hours. Handing in the proof sheets to the censor, I observed at once that his was "a hot potato" to him and he did not know what to do. Through the thin partition wall I heard him telephone to Kaunas to the Ob-Ost, the Supreme Command East, and most likely calls were made from there to Berlin, and occasionally I would overhear angrily voiced "Donnerwetter". At long last, roughly three hours later, I was handed the consored-out newspaper. I looked at it: a red penciled cross covered the entire text of the Declaration of Independence — the entire page one. On the remaining pages — little was left without red pencil marks. So I mused: all in order, the issue will not be out — legitimately, and I can peacefully go to bed.

However, Mr. Klimas had told me that he would wait for me at the editorial office for news about the censor's action. And so I returned to the office. Klimas had made arrangements in advance with the printing shop owner, a good Lithuanian Martynas Kukta. Klimas just looked at the censored copy, called up Kukta on the phone to say a code word, and then told me: "Let's go to the printer's". On the way there I learned from Klimas that — no matter what should happen — we were going to print several hundred copies of the abridged newspaper with the text of the Declaration of Independence and distribute them clandestinely.

At the printing shop we found only the owner Kukta and his assistant Antanas Dirse. Other workmen were dismissed and told that no issue was to be reset and printed. The four of us locked the final plate forms and the machines began turning. We printed, as I recall, about five hundred copies of the newspaper. The very same night these copies then were distributed all over the country.

More secretive was the process of smuggling the Declaration out of the country. I remembered that Miss Jadvyga Chodokauskaite had payed a significant part in this operation. She is now Mrs. Tubelis. In reply to my request for details she wrote as follows:

As you undoubtedly recall, the Germans were publishing their newspaper in Vilnius, the Zeitung der Zehnten Armee. One of the editors there was a great friend of Lithuania and the Lithuanians — he was the Alsacian writer Woehrle. Having arrived in Vilnius with the German army, he became enchanted with Lithuanian history and the Lithuanian determination to reconstitute their country's independence. He learned the Lithuanian language and was ready to help us in whatever way he could. It is quite natural that Taryba people thought of him at once when the problem of transmission of the Independence Declaration to Germany arose. It was arranged with him that the text of the Declaration would be delivered to him clandestinely and that he would take it over to Germany. However, the Taryba people were well known to the Germans and were under observation by them. So I was requested one evening to meet Woehrle in the building of the Lithuanian Society of Sciences and to hand him the said document. One key to the building was given Woehrle, and I received another key. He was to go to the Society's office a little earlier and to wait for me, without switching the lights on and with the door locked. I entered the building using my own key. I handed him an envelope with the Declaration, in the darkness, and left the building again. He was to leave later. Of course, being a German soldier, he had exposed himself to a great risk. Several days later he notified us that he had accomplished his mission.

According to dr. Jurgis Šaulys, the text of the Declaration was sent out to Berlin to the Reichstag Deputy Erz-berger that very night. The fact is that the "Vossische Zeitung", the "Taegliche Rundschau" and the "Kreuz-zeitung" pablished the Lithuanian declaration of independence as early as February 18th, and on that date Chairman Groeber of the Catholic Zentrum read the text in the plenary session of the Reichstag. But the German government looked very unfavorably on the matter and enjoined other German newspapers not to publish the text and to make no comment regarding this declaration.

The Ob-Ost chieftains in Lithuania were enraged by this turn of events. The Tenth Army Chief of Staff Ahn-ke intended to arrest all members of the Taryba, but he was restrained by the new head of the military government who reasoned that such detention would be harmful to Germany in the light of world public opinion. Thus the occupational regime was obliged to suffer the presence of the Taryba for a while longer.

The Taryba sought to improve somewhat its relations with the Germans. A delegation of three members: dr. Šaulys, Rev. Justinas Staugaitis and Jonas Vileišis, was authorized to proceed to Berlin and to make reassurances that the Act of February 16th had no bearing on future German-Lithuanian relations and would not cancel the provisions regarding such relations referred to in the statement of December 11, 1917. The Treaty of Brest Litovsk was then pending in the Reichstag for ratification, and before ratifying it — the Reichstag was pressing the government to normalize its relations with Lithuania. Pressed by the Reichstag majority, the Reichskanz-ler finally secured and handed to the Taryba delegation a Kaiser's writ dated March 23rd recognizing the independence of Lithuania — on the basis, however, of the December 11th declaration.

Before coming to address you here, I attempted to verify the time when the February 16th Declaration had become known in the West, and particularly in America and among the Lithuanian Americans. Dr. Julius J. Bielskis, presently the Honorary Consul General of Lithuania at Los Angeles, in 1917 and 1918 had been the President of the Lithuanian National Council in America and head of the Lithuanian Information Bureau in Washington. He informed me that it is difficult to fix a definite date inasmuch as news from German occupied Lithuania seeped through to America slowly and irregularly, and the information was received with great reservations regarding the authenticity. It is a fact that no mention of the February 16th date was made at the Lithuanian General Assembly at New York of March 13-14, 1918, and evidently the declaration was not then known. On May 3, 1918, a fairly large Lithuanian American delegation was received by President Woodrow Wilson at the White House — and the declaration of February 16th was not mentioned in the memorandum presented to the President. Lithuanian Americans referred most commonly to the decisions adopted by the Lithuanian Conference in Vilnius in September 1917.

The conditions in German-occupied Lithuania were not at all ameliorated following the declaration of independence and the recognition of such independence by the Kaiser. The Ob-Ost paid no attention to the Kaiser's promise of "finding the necessary means for the re-constitution of a self-governing Lithuanian State". A collection of pertinent wartime documents — the correspondence between the Taryba Presidium and German officials in Lithuania and at Berlin — was published by Petras Klimas. The bitter struggle between the Taryba and the Germans is graphically documented. The German military government sabotaged the efforts of the Taryba. Repeated requests by the Taryba to ease the inhuman burden of food requisitioning were ignored. A loud and shrill German "Nein!" blocked Taryba's political movements, viz., the decision to rename itself "Valstybes Taryba" — "The State Council", the decision to co-opt more members, even the decision to invite Prince Urach of Wuerttemberg to assume the royal Lithuanian throne.

These conditions persisted until the downfall of Germany's military effort. In September 1918 the German Western .effort reeled back along the entire front and Hin-denburg himself urged the government to explore peace possibilities. This situation at once changed the political relations with regard to Lithuania. Chancellor Hertling was obliged to resign. The new Reichskanzler — Prince Max von Baden — on October 5, 1918 stated in the Reichstag for the first time that Germany leaves to the Lithu-nian State itself to determine its relations with its neighbors. Consequently, the burdensome problem of "eternal conventions" with Germany was solved: Lithuania was free.

In Lithuania, however, the

occupational German military regime would hear nothing of any changes

in the situation. The requisitioning continued with full brutal force,

denuding Lithuania of foodstocks. The Germans would not transfer any

civilian administration to Lithuanians and would not allow formation of

any military units, not even a native police force. And when on the

Armistice Day — November 11, 1918 — the first

Lithuanian Government was formed with Prime Minister Aug. Voldemaras at

its head — this was but a nominal government with no actual

powers of governing. The real foundations of the Lithuanian State were

laid only in the last days of December and in January 1919 when the

second Cabinet of Mykolas Sleževičius pushed the organization of local

governing bodies and called volunteers, mobilized the officers and

organized nuclear Lithuanian armed force. Had Lithuania been able to

form a 20-30 thousand armed force in the last two-three months of 1918

— history might have followed different paths. Most likely

the Russian Red Army would not have occupied Vilnius and most of

Lithuania, there might not have a-risen the Vilnius problem to plague

Lithuania's relations with Poland. Nevertheless, the period of

independence to 1940 remains a bright period of great exertions and

great achievements: in those two decades Lithuania achieved more in

agricultural and industrial development, in educational and cultural

progress — than during the long 120 years of barbaric

oppression under Russian rule. The fight for freedom, progress and

democracy must be continued. Lithuania must regain its sovereign

independence free from the stanglehold of Moscow.