Editor of this issue: Anatole C. Matulis

Copyright © 1968 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 14, No.1 -

Spring 1968

Editor of this issue: Anatole C. Matulis ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1968 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

A GLANCE AT THE DEVELOPMENT OF LITHUANIAN ART AND THE XYLOGRAPHY OF PAULIUS AUGIUS

ALGIRDAS KURAUSKAS

Soon after the restoration of Lithuania's independence, an entirely new

type of Lithuanian artist emerged in record time. He surpassed his

predecessors in his modern outlook toward art, esthetics, and the idea

of creation. The numerically small but qualitatively significant new

generation of artists, graduates of the Art School established in 1923,

freed themselves from the provincialism that dominated the young state

and left an example and stimulus for the generation of painters that

followed. During the brief existence of the reconstituted Lithuanian

State the new Lithuanian art, which matured under the influence of

native folklore and in the Western intellectual tradition, managed to

preceive, although somewhat belatedly, the pulse of the leading art

movements abroad and grasped their meaning and essence.

The Old and the New

The cultural atmosphere in Lithuania at the time was not favorable to a creator of pure art, despite the loud talk about artistic reconstruction in the farmer Grand Duchy of Lithuania, for centuries culturally and economically devastated by its neighbors, in the past geographically distant from the European centers, but still maintaining its western features. It would be less than objective to assert that the artistic life of Lithuania at that time, —although, admittedly, somewhat provincial, — was at a scandalous level with regard to the search for new paths in fine arts, or exclusively typical for Lithuania. The new state, although an old nation, faced in its period of reconstruction unexpected and heretofore unknown cares. The problem of an authentic and at the same tinje European culture arose in all its actuality and importance.

Northern Europe never gave rise to great painters. The influential schools of art clustered in South and West Europe. Byzantine (and Russian Orthodox) painting never took root in Catholic Lithuania. Only the post-Renaissance and baroque art, imported almost directly from Italy, found a fertile soil in Lithuania, although it came late and was modified by local conditions. The same holds true for Poland, the many-year ally of Lithuania. The Lithuanian cultural life developed through Poland and the acquired forms of national duality that are difficult to distinguish: the common people of both nations found the stimulus and the prototypes for their pictorial creation in closely related and sometimes identical sources. The Polish aristocracy and the Church preserved a large part of the treasures of classical art, rapidly vanishing or pillaged by neighbors. As the Lithuanian State and its political power kept declining, the Lithuanian art treasures slipped into the "care" of the neighboring countries. Even the authentic origin of the work of art became appropriated in this process. The art school that operated as part of the old Vilnius University (1793-1813) failed to promote Lithuanian painters of stature, and when Vilnius and Lithuania itself became downgraded to the level of a cultural province, the school could not hold out as a strong and independent institution.

Since the nation's elite had in the past melted into neighboring cultures, Lithuanian artists missed time-hon-ored national instructions. It is therefore quite understandable that when those artists resolved to speak in the language of their own nation and went to search for original means of expression, they felt both lonely and considerably alienated from the surviving strata of the nation — the peasantry. That is how their predecessors must have felt when centuries ago they turned away from their own people, adopted other cultures and were in turn adopted by them, and now are to be found in the cultural history of the neighboring countries and not in that of Lithuania.

The 20th century Lithuanian painter did not feel comfortable in those cultural ruins: everything around was Lithuanian, but nothing was really and tangibly his own, authentic, jealously guarded through centuries and now, preserved in the past and today. The folk art of the peasantry became (or had to become) the stimulus for individual creation, while the Western cultural tradition was to be the guide-post and the measure of consciousness.

For various reasons the artists of young Lithuania for some time kept distance, willingly or unwillingly, from the entire complex of twentieth century Western art movements. Specific conditions of local character retarded the Lithuanian artist from joining that mighty whirlpool, outside of which a full and comprehensive life of an artist is difficult to imagine. One of the most incisive comments on the subject of cultural problems in Lithuania in the early thirties has come from Justinas Vienožinskis, lecturer at the Kaunas Art School and one of its founders, a man who managed to rise head and shoulders above his environment and his time. Vienožinskis on one occasion wrote that

In reviewing the 1933 exhibit of painters of the older generation, Vienožinskis had this to say:

Thus the participants are not looking for esthetic values, but are content with achieving greater or lesser verisimilitude in their depiction of nature or of the body. They emulate almost exclusively the naturalist academicians and fail to assume any tasks that would justify the existence of the already mentioned schools of art — no attempt is made to solve social, religious, or individual spiritual problems; there is no search for historical, social or ethnographic motives; finally, one misses technical know-how, without which a naturalistic depiction of objects of nature is nothing but a lame, helpless parody. .. One cannot, however, impose a common characteristic on 273 works of art by 24 artists. But the general characterization remains valid for the majority of the participants in the exhibit — it excludes them from the aspirations of their epoch, it secludes them from the great art of all epochs (including the Renaissance period). ...(Naujoji Romuva, April 30, 1933.)

But the slogans and the achievements of the Western art movements finally reached the Lithuanian artists and helped them to forget more quickly, at least for a while, the "official" history of Lithuanian art with its lack of any clear-cut classifications, and prompted them to drink from the natural wells of their own spiritual culture. Lithuania had no shortage of such cultural prototypes — primitive and folk art. The call for a search of creative foundations in the wealth of native art was also sounded by those painters of the older generation who saw in their young colleagues the embodiment of original and fresh creation, untouched by middle class values and shallow sophistication.

The direction of the modern movement

in Lithuania

was uncertain. Justinas Vienožinskis wrote about the search for modern

Lithuanian expression in art:

Encouraging the new ideas were a number of lecturers at the Kaunas Art School, including Povilas Čiurlionis, Mečislovas Dobužinskis, Vladas Dubeneckis, Adomas Galdikas and others. They raised controversial issues that in majority's opinion should have been suppressed or mollified; they defended new artistic phenomena not only in Lithuania but also in the Western world. Some of these lecturers had participated in the movements of artistic elite beyond the borders of Lithuania, and all of them could not help but transmit their aspirations to their students. They urged a struggle without compromise against stagnation, provincialism, chauvinism, aca-demistic imitation and copying; they encouraged the students to delve into the creative wealth of their nation, to open their eyes for new ways of expression, to shed any fears of experiment, to grasp the artist's true mission, to comprehend the essence of the contemporary artistic movements in the West, and to take their stand for all that would raise the Lithuanian artist to a status of equality within the venerable Western culture.

The stimulus of these persons led to the formation of groupings which encouraged quite a few Lithuanian artists to embrace new ideas.

In 1930 the Nepriklausomųjų Dailininkų Draugija (Association of Independent Artists) was established as a protest against the old generation of academic artists who dominated the artistic scene and dictated the proper tone. The Association emphasized the individual character of creation, free from academism and from any officially imposed purpose.

In 1932 the Ars group published, in a manner customary in the West, a manifesto, unambigously endorsing the tradition of folk art and its cultivation in individual creation. The relation of the Ars group to contemporary Western movements was quickly noted by art critics. Vienožinskis, for example, in reviewing exhibits by members of the Ars group, wrote:

The recent exhibits by Ars and others lead us to the forms developed t>y our folk art — to primitivism. Today's Europe, exhausted by civilization, seeks to return to that same primitivism. The primitive synthetic trend is today considered one of the modern European movements. The trend received its impulse from the art of the past and from the artistic creation of semi-cultural and even savage peoples. Cezanne and Gauguin, Picasso and Matisse, modern music and all the branches of modern art, in scaling unprecedented heights, look back at the art of peoples untouched by civilization in order to revive their weary spirit. The aims and the goals are the same, although the results are different. Consequently, the Ars exhibit is also different, although in its aims it is closely related to the modern exhibits of other nations; the participants differ among themselves, although they are stirred by the same idea and worship a similar world. (Naujoji Romuva, May 13, 1934.)

In 1933 Forma, an assemblage of young painters, emphasized the primacy of "individual Lithuanian spirit" in creation and thus joined in the new engagement of demanding individualists to preserve the independence of the creative artist even if it meant renouncing official dogma. Paulius Augius was a member of Forma.

In its own time impressionism destroyed the dominating schools of painting and the philosophy of paint-ting itself. This revolution evoked a counter-action — the not less revolutionary expressionism, which emphasized expression as one of the main elements in artistic creation. Yet the young Lithuanian artists of that time worshipped at the shrine of impressionism and eyed admiringly the artistic devices the impressionists had invented, devices that were applicable in painting only. And how could it be otherwise when these young artists were surrounded by painters and were working under the aegis of the primacy of painting in art. According to them, painting, and not graphic art, was the artist's true language. Consequently, the new movements of art in Lithuania based themselves on the norms of painting.

Augius and the Graphic Arts

It is within the general cultural and historical context that Paulius Augius was born, grew and gathered knowledge. He was born on September 2, 1909, in Žemaičių Klavarija, a picturesque area in Northwestern Lithuania. Here he spent his childhood, and the rolling countryside, the religious festivals in Žemaičių Kalvarija during the summer months, the customs of the Samogi-tians remained etched in his mind and his works throughout his studies at the Kaunas Art School, in Paris and exile beyond his native land.

Paulius Augius enrolled at the Kaunas Art School in 1929 and was there when the conflict between the old generation and the modernists reached its organized form discussed above. The years of study were described by Augius' classmate and close friend Telesforas Valius:

The Art School in Kaunas was uncomfortably young; there were no significant museums or imposing monuments of art; an attractive art tradition to be followed did not exist. Direct experience, that basic condition for cultivating an artist's potential, was also lacking. In school and in the more or less professional exhibits, compliments usually went to those talented painters whose work reflected the trends of Western Europe. Post-impressionism remained the newest and latest fashion among Lithuanian painters. Graphic art had no prestige. The work of expressionist wood engravers seemed either alien or inaccessible for Lithuanians. Our graphic artists thought that the new views on painting which dominated the art scene at that time were difficult to put into practice. After a prolonged treatment of graphic arts as an illustrative, supplementary, secondary branch, belonging to the category of applied art, not only the Lithuanians, but also international art authorities denied any possibility of monumental effects to graphic arts. The Japanese woodcuts, so much admired by Toulouse-Lautrec, were still a terra incognita in Europe; Gauguin's esteem for folk art engravings and for primitive art was regarded as fascination with an oddity that might provide inspiration and much less as interest in an original and authentic form of art.

The German expressionist movement wrested the graphic arts from the hands of snobbish experts-collec-tioneers who patronized it as a dying species, valuable only for its technical virtuosity or historical connotations. But Munch, Kirchner, Nolde, Feininger, Pankok, Schmidt-Rottluf, Rohlfs and other German expressionists were rarely mentioned or discussed in Lithuania at that time. Judging from the press, there was also little mention of Gauguin's woodcuts, Kandinsky's early engravings, of the lithographs of Toulouse-Lautrec. Expressionism, one of the most dynamic and influential art movements in the 20th century, was not a popular subject of discussion. Painters were still fascinated by the impressionist heritage, the sculptors were wavering between the classicists and Maillol without reaching Rodin's synthesis, kept looking for examples in Duerer. The latter managed only rarely to tear themselves away from the academic stroke, sometimes substituting for it a more primitive literal copy of the ineptness of folk art engravings, unable to perceive the essential elemental power and directness of the primitive artist, described by Gauguin a long time ago.

Perhaps because the engravings of some Polish and Russian graphic artists were nothing but a direct paraphrase of folk art, some young Lithuanian artists turned their eyes to the Slavs. The Polish engravers Tadeusz Cieslewski, Wladyslaw Skoczylas, Janina Konarska, the Russians Kravchenko and Favorski, were considered as worthy of emulation not so much because of their technical superiority as because of their topical themes — that's how folk art can be transformed into sophisticated classicism!

Justinas Vienožinskis was one of the people who discovered some spirit of the Russian graphic art in the works of Paulius Augius (and Antanas Kučas), shown at the 1935 Survey Exhibit of Lithuanian Art. Yet the conclusion came readily that among the painters "who had submited to the spirit of the Russian graphic artists", there were some who, according to Vienožinskis, showed more independence, originality and remained basically untouched by that influence. It did not take long for Paulius Augius to exorcize the spirit of Russian graphic art. Several years later he created a cycle unequalled in quality or originality in Lithuanian graphic art at that time. Some graphic artists of Augius' generation were, unfortunately, denied the chance to liberate themselves from the influence of a foreign, in this case, Russian spirit.

It is safe to assume that the group of young graphic artists, formed in the Kaunas Art School by Adomas Galdikas, have developed views that emphasized the self-sufficiency and independence of graphic art. But while proclaiming freedom for graphic art, the group could not prevent some uniformity among its members. Only a few members of this group were able to get rid of group conformism in an early stage. Marcė Katiliūtė, Viktoras Petravičius, Vaclovas Rataiskis-Ratas, Telesforas Valius, Antanas Kučas and Paulius Augius, although less influenced by group conformism than the others, retained the formalistic features of their school even after their creative roads had branched and parted and after they had attained individuality and maturity.

Principal Works of Augius

All the xylographic works of Augius' post-graduation period bear the stamp of the group and not, as it is not quite correctly imputed to him, the influence of the Polish and Russian graphic art. Such are also the early works by Augius: "Grybautojos" (The Mushroom-gatherers), 1935, "Rugių rinkėja" (The Sheave-gatherer), 1935, "Kęstutis ir Birutė", 1935, etc.

But as an artist Augius was really born in Paris, where he studied between 1935 and 1938 in the L'Ecole National des Beaux Arts and Conservatoire des Arts. Having chosen, while yet in Lithuania, the material in which he would realize his world, he was not trying upon his arrival in Paris to solve the problem of what he would have to do but sought an answer to the question how, i. e. the question that can be answered only after one has answered the first querry. It was in Paris where some of his best work was done.

Among the things Augius brought with himself to Paris was the imperishable landscape of Žemaitija (Samogitia). He created his famous "Malda" (Prayer) that was to become his trade-mark, although it was not necessarily his strongest work. Most of the compositions inspired by that same Samogitian life and his personal romanticism disclose a concealed and up to that time unrevealed black and white world of Lithuanian themes, equalled only by the elemental power of Petravičius' linoleum cuts, the woodcuts of Ratas created under the influence of the expressionists, and the xylographic works of Valius with their theatrical flavor. In the years to come this quartet of graphic artists rallied for a new, expressive and powerful creative statement that had nothing to do with the past.

While in Paris, Augius perceived with new eyes the ancient villages of Samogitia, hardly touched by the passing of the centuries, the pantheistic people of the region, its mystical cemeteries, its landscape ignorant of historic time. He had so much new to tell that his woodcuts seem to be quite oblivious of the difficulties of the chisel. "Bažnytkaimis Lietuvoje" (A Village in Lithuania) seems to have prompted him to launch an entire series on the same theme. The chronology of his works created during 1936-1938 is difficult to establish, but it is clear that "Malda", — a work that requires a special treatment in discussing the formation of Augius' style, — belongs to that period. What matters here is not the theme or the somewhat illustrative symbolism that is obvious in the literary manner, but a novel task and a sharp turn in the evolution of his form.

At that time Augius had already become acquainted with the expressionists and had grasped their heritage. His thumbnail sketches, notes and remarks show that L'Ecole de Paris gave him the foundations of a traditional cultivation of form and of structural perception, but it was expressionism that expanded Augius' creative range. In expressionism Augius recognized the power of movement, line, mass and, above all, of the subconscious image. In "Malda" with its three main components (two women, a Samogitian bell-tower, a dispersed background) there is no further fascination with baroque texture; absent are the cleverly concealed strokes of the chisel, the silvery planes nuanced in fine lines, the fait decorati-venesss. Instead the line of design is broad, primitive, direct, without a trace of artiness; the distribution of black and white spots is unexpected, consciously illegible, and the totality strives for reciprocal harmony of abstract elements; only those basic shapes of things are elucidated that are indispensable for the perception of the idea. This is a consummate non-objective composition, rich and eloquent in its miniature world. It is exactly the texture of "Malda", luxuriant and withdrawn from reality, which endows this work with tragic coarseness and rusticity — with its endlessly oppressive sky, the unbearably heavy peasants' hands, and the impression of an outcry permeating a small bell-tower.

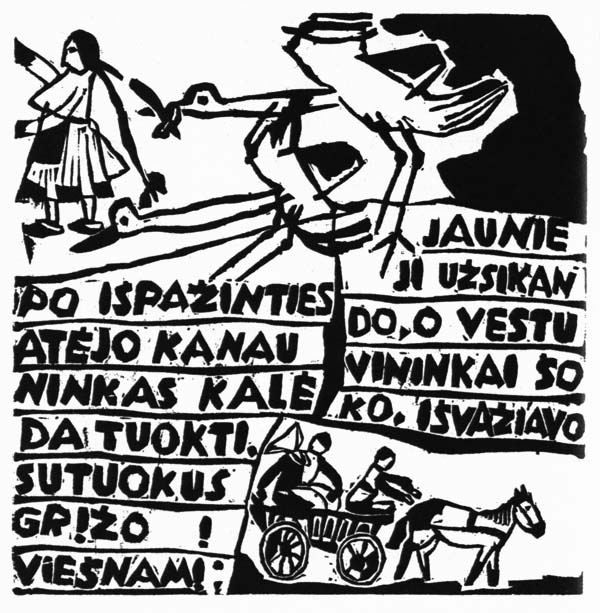

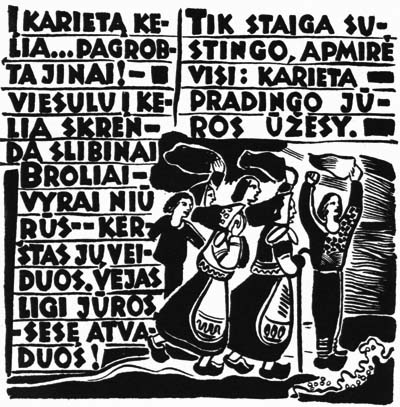

With "Žemaičių Vestuvės" (Samogitian Wedding), a cycle of 78 woodcuts, illustrating the wedding story by the nineteenth century Lithuanian writer Motiejus Valančius, Paulius Augius ceased to be a regional avant-gardist and became a genuine representative of the European graphic art. This cycle was Augius' diploma work for the L'Ecole Nationale des Beaux Arts and Conservatoire des Arts, Paris, presented in 1937. This work earned him a Prix D'Honeur in an International exhibit in Paris in 1938. It also marks his entry into the ranks of the pioneers of the Lithuanian art book. "Žemaičių Vestuvės", however, is more than an ordinary artistic illustration of a book; with this cycle Augius has created the prototype, the idea and the perception of modern illustration and of the art book. It is the credo of Augius as an illustrator and a work that transcends its time, place and ethnographic boundaries. Nevertheless "Žemaičių Vestuvės" is a pronouncedly Lithuanian work — not because of its Lithuanian theme or of the artist's nationality but because it discloses in the unversal language of graphic art the innermost world of the nation and its individuals, its vitality, and the strangely heterogeneous nature of its people — its archaic and modern elements.

"Žemaičių Vestuvės" differs considerably both from the works discussed earlier and from his later creations. For the first time the artist permits the domination of the black line on white; he also does not conceal the traditional technique of the engravers of the Middle Ages and of the early Renaissance — by a minimal use of strokes and of black, he forms contours of shapes which are then filled with light-hued water colors.

In this cycle Augius adopts Picasso's, Matisse's, Bra-que's and Mailliol's manner of art book illustration. He does not draw or interpret the text of Motiejus Valančius in some excessively refined calligraphic style, but simply writes letting his pen travel where it may — coarsely, without embellishments or stops, retaining the natural rhythm and the accidents, integrating the linear drawing that flows into the text, and in general not as much illustrating as endowing the text with a new, unexpected and peculiar atmosphere, which is deliberately set apart from the reportorial tone of the author of the text. Each page is a self-sufficient graphic unit even if one takes it out from the context of the book. In the text and in the illustrations Paulius Augius creates a Žemaitija of his own. His concern is with the synthesis of the subject, and he does not seek to portray the everyday reality or the individuality of the events and characters — all must be typical.The originality of Augius' illustrations lies in his ability not to see the details, to reject inessential things, and to retain the primal element, the essence, the common denominator. In "Žemaičių Vestuvės", man and buildings, cattle and trees, agricultural implements and all the other stage properties are integrated, like the many blending voices in a Lithuanian folk song, into a rhythmical tapestry. Deliberately and shunning any imposition he abandons perspective, the conventions of anatomy or of proportions, and thus imparts to his objects an unexpected, uncommon and strange aura of the grotesque. However, the Chagallian mood, prominant in the graphic art of Viktoras Petravičius, is absent from Augius' work, although both artists drank from the same sources. Whereas Kuzmickis and Kučas, once related to them, turned to Slavic decorative realism, Augius, Ratas, Valius, Petravičius and to some extent Mečislovas Bulaka veered from the then accepted convention to an expressionistic concept of engraving, which reached them via the Japanese woodcuts. Yet no one among them disolved all ties with folk art ornamentalism. It is conceivable that Paulius Augius looked for an answer directly in the old Japanese graphic art, Persian miniatures, and medieval engravings, not forgetting the dowry chests of Žemaitija. These direct sources are suggested by Augius' sketches, paraphrases and outlines. Augius does not seem to have taken direct interest in folk art engravings, although he followed the fashion of the time by giving it some study. "Že-maičių Vestuvės" is Augius' self-liberation manifesto and points to the direction of the quest in his later work.

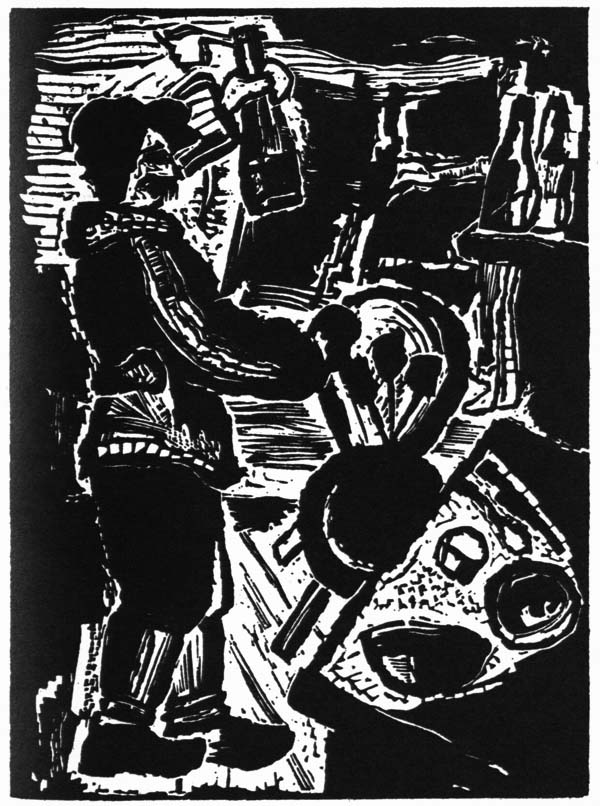

In 1937, while still in Paris, Augius also created the "Petras Kurmelis" woodcut cycle, which is stylistically quite different from "Žemaičių Vestuvės". The compositions of the Kurmelis woodcut are sealed, chained, featuring large basic blak-white spots, modulated by vibrating, nervous and inventive texture. The dramatis personae and their environment are realistic objective, individualized, and in this sense antithetical to "Žemaičių Vestuvės". The entire cycle has been executed in an even intensity but without repetition or monotony; each illustration is a close-up or a variation of the leading motif, the events and the environment are common, earthy, saturated with rustic coarseness. The note of pietism, recognizable in the work of many Lithuanian artists, also echoes in the interior and exterior scenes of "Kurmelis". The cycle has been done in massive, broad chisel strokes, without pausing at details. The drawings of the individual components are treated fragmentarily — without an effort to accent or to elucidate them, they are brought together in a "soft" textural mass. With "Kurmelis", Paulius Augius again emphasizes his acclimatization in the expressionist positions.

During 1938-1939 Paulius Augius concentrated himself on a series of large size engravings, "Žemaičių Kalvarijos" (The Samogitian Stations of the Cross). Until then no artist had ventured to take such a simple and pure look at the gray Samogitian vista. The silvery black - white rural landscapes, steeped in everyday reality, became miniature epic panoramas redolent of boundless nostalgia. Whoever has roamed in the dark fallow fields of Žemaitija, has sought coolness in the shadow of gray bell-towers, or has longed in his weariness for the thatched roofs drowning in the horizon's line, he will greet the Samogitian day crystallized in those compositions as a veritable holiday.

"Žemaičių Kalvarijos" and some other works of the later period mark Augius' turn in a new direction with regard to form. In his search for concrete graphic means of expression for his ideas, he found an original stylistic solution for the objects he depicted and avoided the artificial textural ornamentation, so tempting in his subject matter. But while the first works in the series came out monumental, freely executed, and showed an economy of line, texture and the components, in an attempt to express much with a few things, the later works on the same and similar themes became increasingly overloaded with such an abundance of graphic elements that in some cases discord became unavoidable. In the further evolution of similar works, Augius' shrines, houses, trees and exploding suns became unlimited and were thus transformed from his trade-mark into a cliche. This period, insignificant in the creative sense, coincides with the end of Lithuania's independence and continues until the early aftermath of World War II.

During the occupations of Lithuania by Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany during World War II, as well as during the post-war period, while a political refugee from Communism in various Displaced Persons camps in Western Europe and, since 1949, as an immigrant to the United States, Augius' creativity was notably affected. What perhaps mattered most for Paulius Augius in this period was his submersion in the creative process as a way of human survival. The very fact of work was important. His neighbors and friends inform that even in the tragic circumstances of a war refugee, Augius never stopped working, although he did not enrich his output with sig-nifitantly creative, new and exceptional works. Among his major works of this period are: Žemaičių Simfonijos" (Symphonies of Samogitia) 1947, a sort of a sequel to the cycle "Žemaičių Kalvarijos"; "Žalčio Pasaka" (Serpent's Tale), 1947, illustrations for a folk tale (poem by Salomėja Neris); and his last large-scale cycle — the illustrations for the posthumous poetry collection of Vytautas Mačernis. Perhaps only "Žalčio Pasaka" merits a brief commentary.

The radical shift which typifies each

of his major

works is also evident in "Žalčio Pasaka", whose form still retains some

similarity with that of his earlier creations. In this tale Augius

returns to the flat tratment of objects, already seen in "Žemaičų

Vestuvės", but in this case the flatness is enriched by rhythmic

strokes and a paraphrase of folk art ornaments (decorative rural

painting). The masses of individual illustrations are kept in close

clusters; the illustrations of the text are no more atmospheric (as in

"Žemaičių Vestuvės") but rather supplementary interpolations next to

the main illustrations on the right-hand page of the book. The uniform

size of the illustraions, the hermetic composition and recurring

elements lead to monotony.Yet one needs only to submerge oneself in the

rhythm of the poem, to turn the rich pages slowly, and one again

becomes fascinated with the artist's imagination, inventiveness and his

remarkable perseverance that enabled him to maintain stylistic unity in

the xylography.

The landscape of their country's nature and spirit was for Paulius Augius and his contemporaries a source of veneration and enchantment. And yet they did not find enough elbow room within that landscape. The already available means of graphic art, — the direct paraphrase of folk art dressed up with a cheerful but superficial mantle of so-called decorativism, — were not sufficient for Paulius Augius to construct a new creative vocabulary. Not many were able then to read the handwriting of Augius and of his contemporaries; at home he was understood only by a handful of "odd people". It was nowhere else but in Paris that his efforts found an echo and his works received warm recognition. Only in later years Augius became accepted by his countrymen as well.

As one looks at him from a perspective, however, it becomes obvious that he was neither an extreme revolutionary nor a harbinger of new esthetic theories. In the European art circles his creative manner was then en vogue in the most positive sense. Although in the context of early 20th century art the work of Augius cannot be classed with the creations of protesting innova-tionists, one cannot escape noticing that in the narrower area of xylography he has quite early charted an independent path — original, shunning imitation, and without a prototype in Lithuanian graphic art. What he gave was the imperative for the cultural renaissance:1 the confidence in the spiritual wellsprings of his own nation, while at the same time searching for artistic identity in the ancient cultures of Europe.

Paulius Augius died unexpectedly following a short illness on December 7, 1960. There is no question that he was one of the most creative graphic artists that emerged from the Lithuanian countryside during a relatively brief period of Lithuanian independence. He and his colleagues from the Kaunas Art School set the standards and direction that have been followed by Lithuanian graphic artists in his homeland and beyond Lithuania. The future generations of artists no doubt will be indebted for the high artistic tradition which Paulius Augius helped to establish. Even beyond the significance of Augius to the development of Lithuanian graphic art, his work is of universal value. This is testified by the numerous international exhibits of his works and their ownership by internationally renown museums.

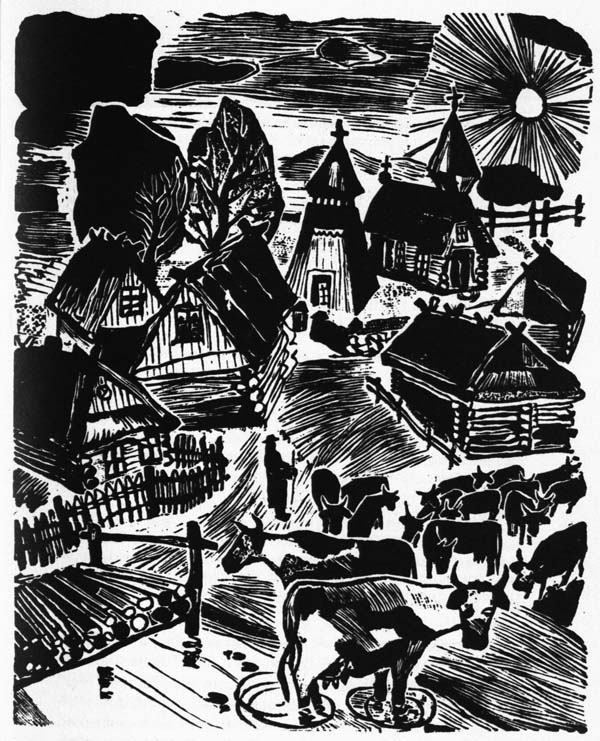

VILLAGE IN LITHUANIA

(1937)

Original woodcut

7½" x 9½"

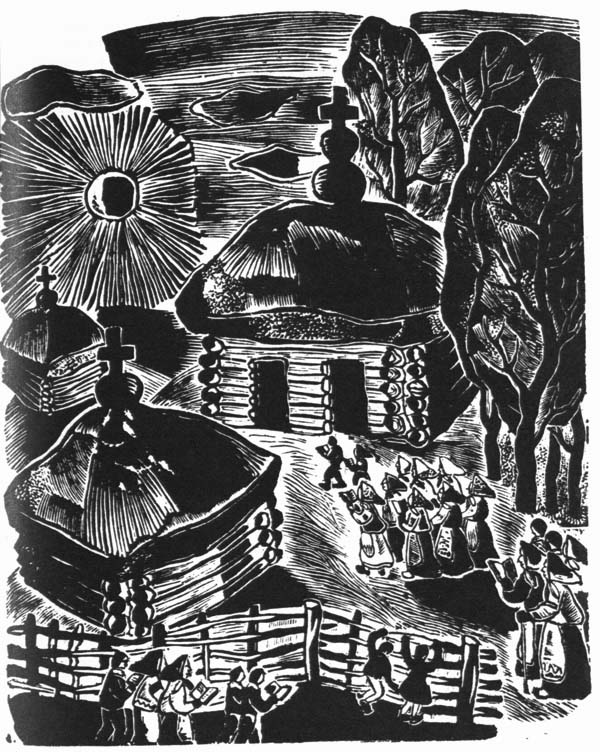

PRAYER (1937)

Original woodcut

7½" x 9½"

STATIONS OF THE CROSS IN

SAMOGITIA (19S8)

Original woodcut

7½" x 9½"

|

|

| Illustrations for SAM0GITIAN WEDDING (1938) Typical spread (orig. woodcuts approx. 5" x 5") | |

|

|

| Illustrations for SAM0GITIAN WEDDING (19S8) Typical spread (orig. woodcuts approx. 5" x 5") | |

Illustration for PETRAS

KURMELIS (1935-38)

(Original woodcut

4½" x 6")