Editor of this issue: Anatole C. Matulis

Copyright © 1968 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 14, No.4 -

Winter 1968

Editor of this issue: Anatole C. Matulis ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1968 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

THE FIRST NATIONAL SYSTEM OF

EDUCATION IN EUROPE

The Commission for National Education of the Kingdom of Poland and the

Grand Duchy of Lithuania (1773-1794)

JOHN A. RAČKAUSKAS

Chicago State College

INTRODUCTION

The Commission for National Education of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Polish: Kommissya Edukacyi Narodowey Korony Polskiey Y. W. X. Litewskiego; Lithuanian: Lenkijos Karalystės ir Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštijos Valstybinė Edukacinė Komisija, hereafter refered to as The Educational Commission) was established in 1773. By purpose and design the Educational Commission combined the educational systems of both Lithuania and Poland under one national controlling body, thus directly taking over the responsibility for education and becoming the first "Ministry of Education" in Europe.

The organization and work of the Educational Commission predates the establishment of national systems of education in other European countries by 20 to 30 years.1 For example, in France national education was planned by such great educational reform leaders as La Chalotais (Essai d'éducation nationale - 1763), Rolland (Plan d'éducation - 1768), and later by Mirabeau, Talleyrand and Condorcet, but not realized until the man date received in the French Constitution of 1791 and finally the passing of the Law of October 25, 1795. Likewise, in Switzerland a national system of education emerged under the leadership of Swiss Minister of Arts and Sciences Albrecht Stapher only in 1798. In Prussia, Frederick the Great layed the groundwork for a national system of education by the Codes of 1763 and 1765 (General Land Schul Règlement). These were followed by the establishment of the Superior School Board (Oberschulcollegium) in 1787. With the codification of Prussian civil law (Allgemeine Landrecht) in 1794, the principle of state supremacy in education was definitely recognized; but it was only after the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807, that the Bureau of Education was established and national education in Prussia began. Before then the idea of national education remained largely in the statute books.

Polish historians have shown great interest in the educational reforms of the 18th centrury. J. Lewicki, Z. Kukulski, S. Lempicki, and T. Wierzbowski, have published collections of documents dealing with the work of the Educational Commission. Especially Kukulski's collection, containing the principal regulations and directives of the Educational Commission issued between 1773 and 1776, is an invaluable source. S. Kot, S. Tync, H. Po-hoska, have collected and published vast amounts of material, as have B. Suchodolski, L. Kurdybacha, and K. Mrozowska.2 However, most of their works deal with Poland and are only peripherally concerned with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Most of the material describing the activities of the Educational Commission in Lithuania can be found at the University of Vilnius, where all the original school inspection reports dealing with the Lithuanian schools are preserved. These reports have not as yet been completely analyzed. A full and concise history of the work of the Educational Commission and its problems will therefore be possible only after those documents have been thoroughly reviewed. The Lithuanian historians are beginning their work only now, as the limited number of studies cited in this work indicates.

The activities of the Educational Commission have received little attention in the literature of the English speaking world.3 Because of the Educational Commission's historical importance (i.e., it predates most recognized attempts to establish national systems of education) this work will present the Educational Commission's role in the establishment of a national system of education in Lithuania and Poland. Since historians have elaborated more on the activities of the Educational Commission in Poland, greater emphasis will be given tc/ its work in Lithuania. The reader should also be reminded that since 1569 Lithuania and Poland constituted a Commonwealth, with a single jointly elected monarch and a Sejm, but a decentralized system in all other respects. Although the Educational Commission set central policies and provided administrative control over the school systems in Lithuania and Poland, in fact it presided over two separate systems of education — one for Lithuania, and one for Poland. Finally, emphasis on the Educational Commission's work in Lithuania is justified by its more extensive activity and success in Lithuania than Poland.

EDUCATION BEFORE THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE EDUCATIONAL COMMISSION

During the eighteenth century in Lithuania and Poland, as in other Western European countries, educational reforms were in the air. The Enlightenment in effect called for a more rational, practical, and secular approach to education. In addition, the growing commercial and manufacturing activity demanded that education be more practical in orientation and accessible not only to the nobility, but to the peasants and the burgher as well. In spirit and direction the educational reform movement thus was in conflict with the scholastic philosophy and exclusive noble orientation of the educational institutions, which in Lithuania and Poland since the sixteenth century were under the control of religious bodies, especially the Jesuits.

In Lithuania, the Academy of Vilnius (est. in 1579), as well as the vast majority of all educational institutions, was operated by the Jesuits. Other religious orders, such as the Piarists (Patres Piarum Scholarum), were also working in Lithuania, but in number and influence they were relatively insignificant. In 1773, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had 34 middle type schools. Of these schools 20 were under Jesuit control, 8 under Piarist control, 2 under non-Catholic (Evangelical) control, and 4 were operated by the Order of St. Basil.4

Under the impact of the Enlightenment and the changing socio-economic needs of society the Lithuanian Jesuits began educationl reforms during the early part of the eighteenth century. The Ratio Studiorum (1599), which was the basis for all Jesuit instruction, was modified. They removed Greek from the curriculum, shortened the number of hours devoted to classical writtings and made changes in the teaching of classical Latin. They continued to teach scholastic philosophy (which was divided into logic, physics, and ethics), presented in a formal manner facts about antiquity, generally neglected science and practical life subjects, and inculcated a cosmopolitan, as opposed to a nationalistic, viewpoint. In general the schools were designed to serve the needs of the gentry.5

During the middle of the 18th century the Jesuits expanded their curriculum to include modern languages and science. Attempts were made to develop an awareness of the needs of society. Political values and responsibilities were being discussed, and some even entertained the idea that the interests of society in general are above the interests of the individual. However, most of these advanced ideas were introduced only to the gentry and education for the peasants or the burghers was not considered theoretically or practically. The idea of universal public education was still dormant.

One of the major reforms initiated in the middle of the 18th century was by S. Konarski (1700 - 1773), a member of the Piarist Order. In 1740 Konarski formed the Collegium Nobilium in Warsaw. The curriculum of this middle school deemphasized the use of Latin. Religious instruction was still an integral part of the curriculum, which now was expanded to include history, law, architecture, and geography. The younger students were also taught fencing, dancing, and equestrian arts. The completion of the program of studies at the Collegium Nobilium took seven years. The school was a type of finishing school for the sons of nobles, with very high tuition and enrollment limited to 60 students.6

The Collegium Nobilium encouraged other school reforms in Lithuania and Poland. In 1754 the Piarist Order published new regulations governing their schools. The Jesuits followed suit and revised some of their orthodox educational thinking and practice. In Vilnius they established their own Collegium Nobilium in 1751. The Vilnius Collegium Nobilium had a new and revised curriculum, which included such subjects as grammar, speech, philosophy, history, geography, and mathematics. Instruction in Latin as well as in modern languages such as French and German was provided. Using the Vilnius Collegium Nobilium as a model, the Jesuits began revising and reforming all schools under their jurisdiction to conform to the same curricular program. By 1773 the Jesuits had established approximately 15 Collegia Nobilium.7

Besides the Piarist and Jesuit reforms, a number of other significant developments should be mentioned. In 1766 the Royal Military Academy (Szkola Rycerska) was founded in Warsaw (eventually this school developed into Warsaw University and one of its graduates was Tadeusz Kosciuszko).8 The significance of this school is found in its secular organization and aims. It had a lay faculty and was independent of ecclesiastical authority. The curriculum stressed sciences and rationalistic philosophy. The school was well equipped with teaching aids, including complex astronomical models.9

Such developments as the Szkola Rycerska

stimulated further thinking about educational reforms. In Lithuania a

writer in the early 1770's argued that agriculture can be improved only

through a thorough knowledge of the earth sciences and that the

responsibility to impart this knowledge rests with the schools. In 1773

a proposal to establish an Academy of Sciences in Vilnius suggested

that more time be spent in schools on geometry, mechanical arts,

geography, mining, and economics. These subjects, it was suggested,

were functional for the adjustment of the individual in the

socio-economic system.10

The educational reforms, initiated by the Piarists and adopted in part by the Jesuits, as well as other changes, such as lay participation in education, more scientific and practical orientation in curriculum, and an open concern with the problems of education, all contributed and provided the basis for educational planning and reforms of the Educational Commission.

The influence of Jean Jacques

Rousseau's tractate Considerations sur le Gouvernement de Pologne

(1772), in which he presents in outline his views on national

education, is still to be determined.11

DISSOLUTION OF THE JESUIT

ORDER

Until the end of the 18th century, education in Europe was largely in the hands of religious orders. One of the most powerful and influencial of these were the Jesuits, who not only controlled the major educational establishments, but also held vast amounts of property and other assets. This of course was normal and necessary for a religious order whose interests touched many areas of life. In a period of flux and developing counter ideologies, the Jesuits were a likely target for much criticism and attack because of their strong orthodox views toward religion and inflexable teaching methodology.

Unable to withstand pressure from various governments, Pope Clement XIV in his bull Dominus ac Redemptor Noster issued on July 21, 1773, dissolved the Jesuit Order throughout the world. Even before the Bull's announcement the Jesuit Order in Portugal, Spain, France, and Austria had already been disbanded. According to the conditions of the Bull the dissolution would occur only after the announcement was made by the local bishop, who first had to secure the aggreement of the civil government.12 In Lithuania and Poland it was this Bull which opened up the way for the establishment of the Educational Commission.

In Poland and Lithuania the Bull was received by Nuncio J. Garampi, who informed the Polish Chancellor, Bishop of Poznan A. Mlodziejowski. On September 10, 1773, the Bishop notified King Stanislaus Augustus and the senators convened at the Partition Sejm of 1773.13 The Sejm, whose major purpose was to "approve" a partition of the Lithunian - Polish Commonwealth by the three great empires of Russia, Prussia, and Austria, was thrown into turmoil. The dissolution of the Jesuit Order in Lithuanian and Poland would result in an educational crisis in the already problem ridden countries. Although many opposed the dissolution, others were in favor, since with it all Jesuit properties would pass to the state.

The Lithuanian Vice-Chancellor Joachim Chreptowicz (Lith: Jokimas Chreptavičius — 1729 - 1812)14 proposed to the Sejm that a special educational commission be established to continue the work of the Jesuits and the educational system established by them. Chreptowicz proposed to place the educational commission directly under the King. But the senators objected and approved a counter-proposal offered by the Bishop of Vilnius Ignacy Massalski (Lith: Ignas Masalskis — 1729 -1794)15 to place the Educational Commission under the patronage of the King, but to make it directly responsible to the Sejm.16 This proposal was accepted by the Sejm on October 14, 1773.

In accordance with Papal Instructions the dissolution order was therefore accepted by civil authority. The order was announced in Vilnius on November 12, 1773.17 With the announcement the University of Vilnius, which had been operating for more than two centuries, as well as the Vilnius Collegium Nobilium and all Jesuit schools and properties passed into the hands of the newly established Educational Commission.

In 1773 the Jesuit Order in Lithuania and Poland had 2,359 members (1,177 priests, 599 clerics, and 583 brothers). The Jesuits had 51 colleges, 18 residencial houses, and 60 mission stations. They kept 66 schools functioning (23 middle schools, 15 Collegia Nobilium, 2 seminaries, and 2 universities). In the Lithuanian Province alone there were 643 members of the Jesuit Order.18

Nuncio Giuseppe Garampi informed the Holy See of the Sejm's decision to use the Jesuit properties for education. On December 18, 1773, in a letter addressed to the King and the Chairman of the Educational Commission Bishop Massalski, the Pope sanctioned this decision and expressed his pleasure that two bishops were members of the Commission. He also expressed the hope that all religious and philosophical instruction would remain under the control of the Bishops and that all professors and teachers would be of the Catholic faith.19 Thus ended two centuries of Jesuit work and dedication to religion and education in Lithuania and Poland. Their educational responsibilities were now to be carried on by the Educational Commission.

It is interesting to note that Catherine II of Russia did not allow the Papal Bull to be announced in lands taken over by the Russian Empire from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Partition of 1772. When Pope Clement XIV died on September 22, 1774, his successor Pope Pius VI did not object to Catherine's action and on August 9, 1774, .even allowed the remaining Jesuits to enlist new members into the Order.-" Thus education in these lands remained in the hands of the Jesuits. Had the Sejm of 1773 also chosen not to announce the Bull, educational reform would have been retarded and the influence of the philosophical and reform movements of the 18th century would have been minimized. It is also clear that the dissolution of the Jesuit Order was motivated not so much by pedagogical as by economic, religious, and political considerations. Educational reform was in large measure an unintended byproduct of the demise of the Jesuits.

ORGANIZATION AND FINANCES OF THE EDUCATIONAL COMMISSION

The first members of the Educational Commission, appointed by the Sejm of 1773, came from some of the most prominent families in Lithuania and Poland. The Commission initially consisted of eight members who received no compensation for their services. The first members of the Commission were: Prince Ignacy Massalski, Chairman of the Educational Commission and Bishop of Vilnius; Prince Michal Poniatowski, Bishop of Polock; Prince August Sulkowski, Governor (wojewoda) of Gniezno; Prince Adam Czartoryski, General of the Podolian Territory; Joachim Chreptowicz, Vice-Chancellor, Grand Duchy of Lithuania; Ignacy Potocki, Secretary (pisarz), Grand Duchy of Lithuania; Andrzey Zamoyski, night of the Order of the White Eagle; and Antoni Poninski, Administrator (starosta) of Kopajnie.21

Members of the Educational Commission who contributed most to the reforms and organization of the Commission were Massalski, Chreptowicz, and Potocki. The latter two remained on the Commission until its last years (1794). Some of the younger men who took the place of older members were the poet Niemcewicz and the dramatist Zablocki. Bishop Massalski resigned as the Chairman of the Commission in 1777, but remained a member of the Commission. Upon Massalski's resignation all matters pertaining to Lithuanian schools were transferred to Chreptowicz. Even though most of the leaders of the Educational Commission were newcomers to the field of education, they were able to make exceptional gains in the organization and development of the schools in Lithuania and Poland.

|

| The first UNIWERSAL (Proclamation) issued by the Commission of National Education of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania on November 24, 1773. |

| SOURCE: Photocopy of document from the collection of Dr. Stanislaw Kot as reproduced by Z. Kukulski, Pierwiastkowe Przepisy Pedagogiczne Komisji Edukacji Narodowej z lat 1773-1776 (Lublin: Sklad Glowny w Ksiegarni m. Arct, 1923). |

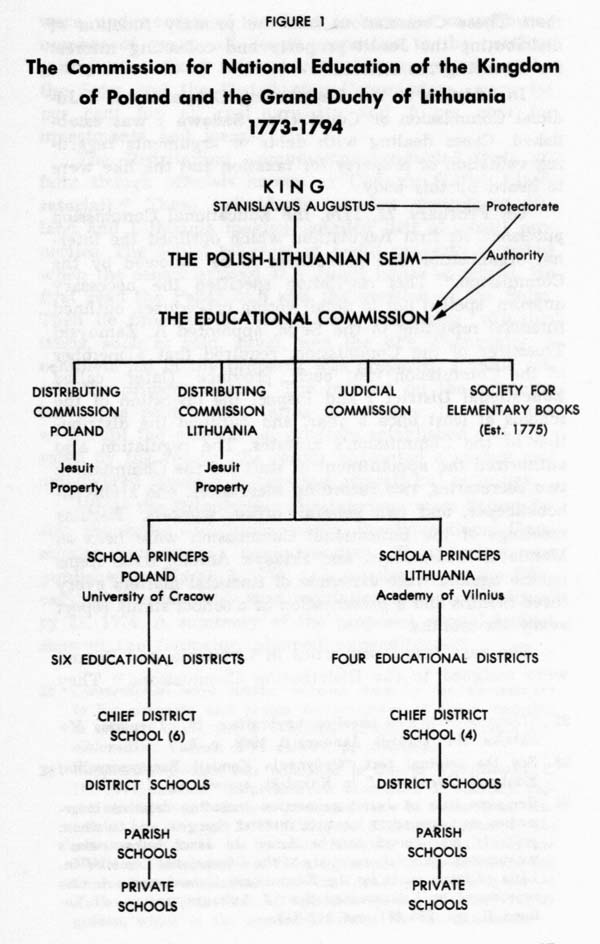

The Educational Commission was charged with the assumption of the administration of all Jesuit schools and properties, control and supervision of all other schools not under Jesuit control (e. g. Piarist), and supervision of instruction in all schools. There was to be no disruption of classes in the schools during the transition of power and control to the Educational Commission. The entire organizational structure of the system under the Educational Commission is illustrated in Figure 1.

In order to carry out these tasks the Sejm appropriated to the Educational Commission all monies to be derived from Jesuit Properties. The Commission was empowered to collect and spend these funds, as long as they were used for education. Two special sub-commissions were established in order to carry out the funding processes: the Distributing Commission of Lithuania (Lith: Dalinamoji Komisija ), with Bishop of Vilnius Ignacy Massalski as chairman; and the Distributing Commission of Poland (Pol: Komisja Rozdawnicza ), with Bishop of Poznan A. Mlodziejowski as chairman. These Commissions had the primary function of distributing the Jesuit property and collecting interest for financing the schools.22

In addition to the Distributing Commissions, a Judicial Commission or Court (Pol: Sadowa) was established. Cases dealing with debts or arguments regarding valuation of property for taxation and the like were to heard by this body.

On February 21, 1774, the Educational Commission published its first Regulation, which outlined the internal organization and procedures to be followed by the Commission.23 This regulation specified the necessary quorum, spelled out in detail voting procedures, outlined financial reporting to the Sejm, appointed A. Zamoyski Treasurer of the Commission, required that a member of the Commission visit each province (later called Educational District) and inspect the operation of the schools at least once a year, and outlined the distribution of the Commission's minutes. The regulation also authorized the appointment of staff for the Commission: two secretaries, two recording secretaries, one archivist-bookkeeper, and two general office workers. Regular meetings of the Educational Commission were held on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Among fixed items on the agenda were a review of financial matters every three months and a presentation of a school status report every six months.

The vast Jesuit properties in

Lithuania and Poland were assigned to the Distributing Commissions.24 They were,

under orders of the Sejm, to lease for an unlimited number of years,

all Jesuit properties to the nobility-gentry at a fixed interest rate.

Interest rates, set by the Sejm and the Distributing Commissions, were

4½ per cent for all real property and 5 per cent for

investments and loans.

The Distributing Commissions conducted their affairs though officials

known as Censors (Lith.: Liustratoriai).25

These individuals traveled throughout Poland and Lithuania making

detailed lists of Jesuit properties. The actual takeover of Jesuit

property occurred when the censor arrived at a Jesuit house or school.

He first read the Papal Bull and the decision of the Sejm. Then he

proceded to seal rooms containing valuable items, such as gold, silver,

and the like. Eventually, a complete list of the property was prepared,

a value set, and the property leased. The interest on the property had

to be paid in two terms in advance. In order not to disrupt the

educational program established and operated by the Jesuits, the censor

appointed a prefect and empowered teachers to continue educational

activities.

While the Distributing Commissions were listing Jesuit properties and

leasing them, the Educational Commission prepared an annual budget.

This budget was published on March 2, 1774, as a supplement to the

Educational Commission's first regulation issued on February 21, 1774.

A summary of the proposed annual budget showed the following planned

expenditures:26

The tri-level school organization reflected in the budget will be

discussed in detail below. The budget reflects the ambitious thinking

and planning by members of the Commission, who projected 2,580 schools

that were to be under their support and direction. This number of

schools never materialized, since by 1783 only 22 per cent of the

parish-elementary schools projected were actually established. The

middle school projection was more accurate with 94 per cent of the

number budgeted in actual operation by 1783.27

The university projection was accurate from the start since the Academy

of Vilnius and the University of Cracow were in operation. The

projected annual budget of 1,956,800 gulden would be needed only in the

case that all 2,580 schools were operative, but since far less than

that number were in actual operation the Educational Commission's

expenses were somewhat less than the projected amount.

Jesuit holdings in Lithuania were by no means meager. In a financial report to the Sejm the Educational Commission showed income received from all sources during the period beginning with actual operations (November 8, 1773) and ending in June, 1776 to be 1,781,354 gulden.28 The same financial report shows total expenditures during the period to be 1,754,824 gulden. The reporting period 1773 - 1776 reflected operations under the Distributing Commissions. Because of charges made against various members of the Distributing Commissions, the Sejm disbanded them early in 1776. Bishop Massalski, the Chairman of the Lithuanian Distributing Commission was accused of misappropriating some 300,000 gulden. Some authors claim that fellow members of the Distributing Commission were more at fault than was Bishop Massalski.29 Bishop Mlodziejowski, Chairman of the Polish Distributing Commission was also accused of misappropriating funds.30 According to a student of the Educational Commission A. B. Boswell: "At first the Jesuit funds had been raided by all the rogues who then led the Polish parliament, and it is estimated that of the 40 million Polish gulden taken over from the Jesuits, over a third part was lost before anything at all was spent on education."31 This inditement along with misappropriations, leasing of choice property to friends at lower valuations, etc., led to the disbanding of the Distributing Commissions. Upon disbanding the Distributing Commissions the Sejm turned over the responsibility for funding directly to the Educational Commission.

The Educational Commission, now in direct control of the funds, found that the annual income from various Jesuit properties was substantially more than had been previously collected. In a projected annual income statement issued in 1776, the Commission showed an expected income from Polish estates of 417,633 gulden and 528,940 gulden from Lithuanian estates; furthermore, interest income was expected to be another 411,577 gulden. Including various other sources the Educational Commission showed a projected annual income of 1,518,967 gulden, which was much closer to the amount originally projected in their budget of 1774.32

It should be noted that monies received from Lithuanian properties were to be used for the support of Lithuanian schools, and monies received from Polish properties were to be used for the support of Polish schools. However, since the Educational Commission was a joint Lithuanian-Polish body, and the Polish had a smaller income from their properties, some of the Lithuanian monies were channeled into the support of Polish schools. The Lithuanian gentry bitterly debated this procedure of supporting Polish schools. They claimed that any excess funds should be used to support the Lithuanian Army. This problem was referred to the Sejm, but it was never solved.33

The Educational Commission was able to operate financial matters more efficiently than the Distributing Commissions. In 1776 a total of 1,016 individuals were paid employees or were supported by the Commission. Of these 29 were employed directly by the Commission, 308 were teachers, 391 were emeritus faculty, 83 were clergy, and 205 were pensioned gentry.34

In 1783 the Educational Commission

had an income

of 1,311,875 gulden. That same year total expenditures were only

1,238,080 gulden. The Academy of Vilnius and the University of Crocaw

each received 150,000 gulden.35

Along with the responsibility of maintaining the schools, the

Educational Commission also provided pensions for retired Jesuits.

Slightly under 200,000 gulden were paid out to them. In a report issued

by a committee appointed by the Sejm in 1776 to inspect the work of the

Educational Commission, we find the following statements:

In general, the work of the Distributing Commissions and later the Educational Commission in finance was satisfactory. Even though plagued by unscrupulous administration, the plundering of Jesuit estates by the gentry, and by the general decline of the Polish-Lithuanian state, the Educational Commission was still able to provide funds necessary to keep educational institutions functioning.

EDUCATIONAL REFORMS — THE SCHOOLS AND THEIR CURRICULA

Decisions on School Structure and Control

During the first month of the Educational Commission's existence the members of the Commission familiarized themselves with the existing conditions in the schools and education in general. It was decided that all schools from the elementary-parish level to the universities must undergo basic reform. On November 24, 1773, the Educational Commission issued its first Uniwersal (Proclamation), which described the Commission's aims and requested suggestions for educational reform.37 This request for suggestions was a new and progressive act in the still "feudal" procedures espoused by the gentry of Lithuania and Poland. It is interesting to note that when Albrecht Stapfer was planning educational reform in Switzerland in 1798 he likewise requested opinions on a national system of education from his more enlightened compatriots and received several hundred such suggestions. Within a short time the Educational Commission received eleven proposals for school reform. Of these, the proposals of A. Poplaws-ki, F. Bielinksi, Piarist A. Kamienski, and Ignacy Potocki merit close attention since they provided the basis for the educational reforms of the Educational Commission. Among those specific proposals, which in one way or another were ultimately accepted by the Educational Commission, the following suggestions deserve mention:38

1. A

proposal to establish a tri-level school system composed of elementary,

middle, and higher schools.

2. An advocacy of a relatively open

enrollment policy for all sodi»'. classes and both sexes.

3. An advocacy of greater emphasis on

instruction in practical and scientific disciplines.

4. A demand for more instruction in the vernacular languages

(Polish and Lithuanian), national history, and geography.

5. A proposal for the establishment of a

system for teacher education.

6. A concern with the obsolescence of existing textbooks and

concrete suggestions for their improvement.

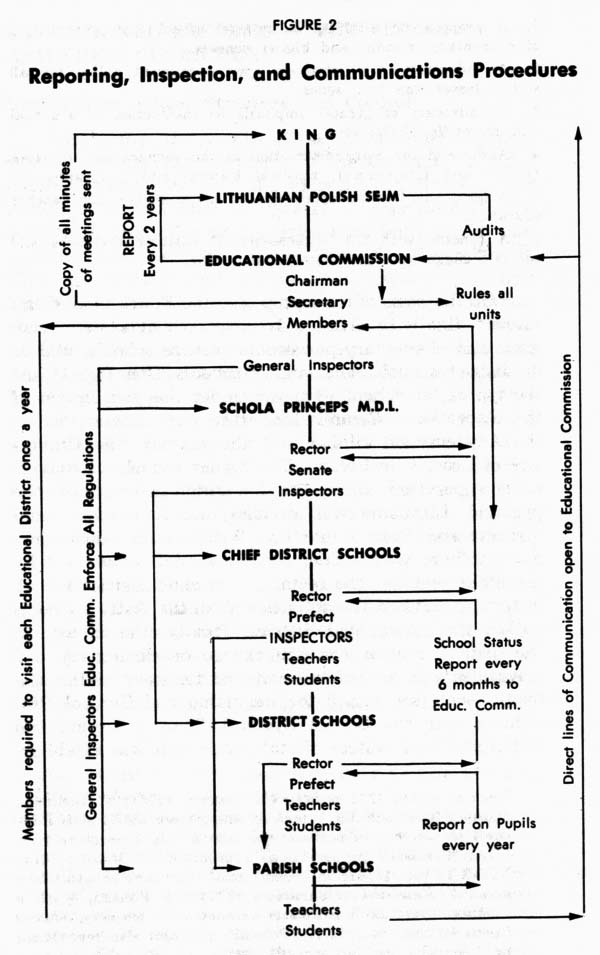

On the basis of such proposals the Educational Commission finally evolved a tri-level school system, consisting of elementary-parish and private schools, middle or district schools, and higher schools (see Fig. 1). At the top of the school pyramid, under the jurisdiction of the Educational Commission, were two universities — the Academy of Vilnius in Lithuania and the University of Cracow in Poland. The higher schools or universities supervised the next lower-middle-level of the pyramid. Lithuania was divided into four educational districts and Poland into six. Within each educational district there was a chief district school, supervised by the higher school. The rector of the chief district school, in turn supervised the activities of all the district schools within the educational district. Finally, the rectors of the district schools were in charge of elementary and private schools within the assigned territory of the district school (see Fig. 2 for Reporting and Control Procedures over the School System). Thus a hierarchical and centralized system of state education was established, combining the various educational institutions into a single harmonious and coordinated body.

The organization chart presented in Figure 1 represents a total developmental picture of the Educational Commission. It must be noted that this structure did evolve over a number of years. The Distributing Commissions were established in 1773 and dissolved in 1776. The total framework of the Commission evolved during the period 1773 - 1783. During September, October, and November of 1773 the Educational Commission considered the establishment of the organizational structure of the middle schools. Dupont de Nemours, Secretary for Foreign Correspondence of the Commission, submitted four briefs regarding school organizational structure. The Commission decided to have two types of middle schools: the chief district schools, and the district schools. The chief district schools were to supervise the activities of the district schools and the district schools were to supervise the parish schools. On October 8, 1775 and December 17, 1775 the Commission assigned the supervision of the Lithuanian district schools to Chreptowicz and Massalski. Chreptowicz was assigned the non-ethnographic Lithuanian areas and Massalski the ethnographic, including the Academy of Vilnius. This organizational structure continued in force through June 13, 1780, when the Commission issued its new reorganiza-tional plan naming the Academy of Vilnius the Schola Princeps of Lithuania, and assigning it direct supervision of the district schools. This regulation also specified that district school rectors had to be elected by popular vote of the area the school served, but election of district school rectors did not occur until 1791. Until then rectors were appointed by the Educational Commission.39

The Educational Commission reorganized school administration in Lithuania and Poland by dividing the countries into educational districts. Lithuania had four districts and Poland six. The educational districts within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were:40

1. Lithuanian District,

with its center and chief district school in Gardinas (Grodno) and

district schools in Lyda, Merkinė, Pastovis, Ščiutinas,

Vilnius, Vyšniava, and Vilkaviškis.

2. Samogitian

District, with its center and chief district school in

Kražiai (Kroze) and district schools in Kaunas, Kretinga, Panevėžys,

Raseiniai, and Ukmergė.

3. Belorussian

District, with its center and chief district school in

Naugardukas, (Nowogrodek) and district schools in Berezovick,

Cholopenck, Minsk, Luzk, Bobrunsko, Neswies, and Sluczk.

4. Russian

District, with its center and chief district school in

Lietuvos Brasta (Brzesc' Litewski) and district schools in Bila,

Dambravica, Pinsk, Zurovic, and Lubiesov.

In order to implement reforms the Educational Commission set out to prepare a series of directives. On May 25, 1774, members of the Educational Commission assigned the writing of two regulations.41 The first one, dealing with parish schools, was assigned to Bishop Massalski, the second one, dealing with district schools, to Ignacy Potocki. Thus, beginning with 1774, numerous directives emanated from the Educational Commission, regulating every aspect of education. One of the original proposals for school reform written in 1773-1174 called for detailed regulations governing every aspect of education. This single proposal was all but forgotten until the number of regulations and directives issued by the Educational Commission became voluminous. On April 4, 1779 this proposal was recalled and plans were begun to compile a school code. Work on the code was sporadic until 1781 - 1782. Finally, on April 13, 1783, the Educational Commission approved the code under the title: Statutes of the Educational Commission. The statues contained not only the old regulations, some of which will be discussed below, but also included many new progressive ideas. For example, the teaching profession was defined as a separate social class, whose members, because of their service and calling, were to be held in the highest respect, and given all honors. Furthermore, members of the Academic class were guaranteed autonomy and were not to be ruled or be responsible to any governmental unit other than the Educational Commission. The original Middle School Regulations were left unchanged by the Statutes. Only minor points, such as time distributions among teachers and introduction of some new subjects, were added.

The Statues of the Educational Commission (1783) were revised by the Sejm in 1790 and in 1793. The first revision eliminated middle school prefects and district inspectors. Members of religious orders were allowed to begin teaching only after completion of a three year program of studies at a Schola Princeps. The 1793 revision was made by the Sejm in Gardinas. The Statues of the Educational Commission later became the basis for Russian educational reforms.42

Elementary-Parish Schools.

The Regulation for Parish Schools was

issued by the Educational Commission in June of 1774.

43 It

should be noted

that the title "Parish Schools" was used by the Commission only as a

convenience, since the lowest administrative subdivision in Lithuania -

Poland was the Parish. The Educational Commission projected one school

for each such parish subdivision in its original planning in 1773. The

Regulation governing these school changed their make-up and

administrative responsibility. The provisions of the Regulation were

grouped into three sections: (1) Teachers and their preparations, (2)

Discipline and order in the schools, and (3) Methods of teaching and

character development. In the introduction of the Regulation Bishop

Massalski, the author, sets forth a rather modern tone for education.

He justifies the Educational Commission's emphasis on primary education

on the grounds that "the child's development, thinking, and behavior

depends on the very first experiences of chil-hood."

The section of the Regulation dealing with teachers and their

preparation displays the rather modern pedagogical outlook of the

Educational Commission. Included in the seven parts of this section are

the following provisions:

—

Every teacher should begin his work at the elementary level,

teach on the secondary level, and only then attempt teaching at the

university or higher level;

— The prevailing attitude that

teaching at the elementary level is debasing should be dispelled;

— The elementary school will be

inspected at least once a year by the district inspector;

— Teachers showing great zeal

and producing good results in the classroom will be rewarded;

—The only right a pastor has in the school is to refer any

problems regarding the teacher to the district school rector, in case a

teacher is ill, the pastor should request a substitute teacher from the

district school rector.

The section of the Regulation dealing

with teaching and character development contains, for example, the

following provisions:

The section of the Regulation dealing with order and discipline in the schools contained 12 points. The main provisions are:

—

12 years are needed for the child to complete his education; education

should begin at age 4 or 5 and continue to the ages of 17 or 18 (this

refers to the entire school structure from elementary to higher);

— Equality should be maintained

in dealings

with all children, be they from the gentry or from the peasant family,

since in the eyes of society they are all simply children;

— Concrete experiences should

be the base of

the teaching act versus abstract ideas which the child may not be able

to grasp;

— Children should be allowed to

be happy and

lively; discipline should not be imposed through fear, but through

mature leadership and understanding the child must be made to

understand through the use of his mental powers;

— The child should be allowed

to act freely, be unrestrained;

— Classrooms should be

decorated with maps,

pictures, drawing, etc. so that the children do not see the school as a

prison, but a pleasant place to be in; the school building must meet

certain specified standards as outlined in the Regulation;

— The teacher must file a

report about each

child to the district school rector on special fonms provided for the

evaluation.

The concluding statements made in the Regulation recognize the fact that "the child is under the influence of the parents, the teachers, and the environment." "Because of this," the Regulation continues, "all efforts of both the parents and the teachers should be directed toward the new generation, so that all from their childhood would have a healthy soul in a healthy body (Orandum est, ut sit mens sana in corpore sano)." The Regulation in many ways conveys the intellectual projection of the Enlightenment. It reflects the sense experience principles of Hume and in part of the Lock-ian school, as well as the thinking of Jean Jacques Rousseau.

The Regulation for Parish Schools did not completely reflect some of the suggestions received in response to the Uniwersal. Even though the proposals for school reorganization suggested the inclusion of practical subjects like agriculture and gardening, these remained unmen-tioned in the regulations. It must be noted that the teaching of religion was also not included in the Regulation. This was due to the strong desire to seperate the responsibility and administration of education from the Church. This desire is further substantiated by the Regulations clear definition of the pastor's authority over the teacher as being indirect and only through the district school rector.

The use of the Polish language in instruction was likewise not mentioned in the Regulation. This latter fact may account for the use of the Lithuanian language in some schools. Lithuanian was taught with the primer Mokslas skaityma raszta lietuwiszka diel mazu wayku.44 An examination of sales records for this primer in Lithuania revealed its widespread use. The first edition of this book appeared not later than 1776, since the Academy of Vilnius Press was selling the book that year. In 1776 approximately 560 copies of Mokslas skaityma... were sold, by 1790 the annual sales increased to 2,350 copies. In contrast, a Polish primer, also available in 1776, sold 510 copies, while in 1790 the number had increased to 2,805 copies. The sales of the Polish primer can in part be attributed to purchases made by the two non-ethnographic Lithuanian educational districts. Nevertheless, the increased sales of the Lithuanian primer can be used as an indicator of the rise in literacy and increased study of the Lithuanian language.

The implementation of the Regulation for Parish Schools was two-fold. The Educational Commission sent inspectors to all educational districts with copies of the Regulation and orders for its implementation. Along with this official action the Chairman of the Commission, Bishop Massalski, used his ecclesiastical post to encourage the establishment of parish schools. On March 24, 1774, even before the approval of the Regulation, Massalski promised the Educational Commission that he would try to establish a school in every third parish.45 In 1774 he received 18,500 gulden, which was to be given to 11 pastors for the establishment of schools; and in 1775 he received from the Education Commission 14 paid inspectors as well as a budget of 164,000 gulden for the support of these schools. Bishop Massalski, with the cooperation of other Bishops, issued a pastoral letter to all parishes in Lithuania, requesting that all pastors agree in writing to establish parish schools, which would be under the jurisdiction of the Educational Commission. Massalski and Chreptowicz were deeply concerned with the peasant class. Even before they assumed duties on the Education Commission, both men released their serfs and encouraged others to do likewise. Their concern for the peasant was shown in their efforts to establish a universal system of education, which would not discriminate against the peasant class. Their efforts met with limited success since the gentry was not as progressive and liberal in thought.

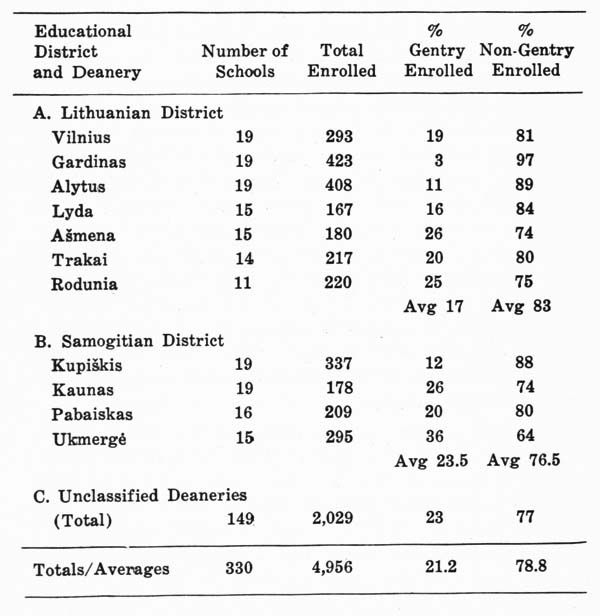

By 1777 the Educational Commission's efforts began to produce results (see Table 1). There were 330 parish schools in operation. Reports show that of the total 4,956 pupils attending 78.8 per cent (3,973) were peasant and burgher children. The 21.2 per cent gentry children enrolled indicated that more than a token number of the gentry were sending their children to parish schools. The gentry enrollment in Samogitia was on the average higher than in the Lithuanian district. The location of a middle school in an area did not alter the percentage distribution of enrollments, for example, Ukmergė had a middle school, but still had a 36 per cent gentry enrollment in the parish schools, while Pabaiska, which did not have a middle school showed a gentry enrollment of 20 per cent. Likewise Vilnius, which had a middle school showed a gentry enrollment of 19 per cent and Trakai, which did not have a middle school, had a 20 per cent gentry enrollment. The case of Gardinas which had a chief middle school is an exception to these examples with an enrollment of only 3 per cent gentry children. In 1777 in the six Polish districts there were approximately only 120 parish schools, or only 26 per cent of all parish schools under the Educational Commission.

| TABLE 1 ENROLLMENTS BY SOCIAL CLASS IN PARISH SCHOOLS OF EDUCATIONAL DISTRICTS IN THE GRAND DUCHY OF LITHUANIA, REPORTED BY DIOCESAN DEANERIES FOR THE YEAR 1777 |

|

| SOURCE: Data for

number of schools and enrollments taken from: J. Gvildys, "Edukacijos

Komisijos Švietimo Darbai Lietuvoje," Židinys (Kaunas),

Volume XIII, No.: 5/6 (76-77) (1931), pp. 491-492. NOTE: Totals reflect only 18 of 22 Diocesan Deaneries reporting. |

In 1781 there were 276 parish schools in Lithuania with 3,391 students, while in 1782 the number of schools dropped to 251 with an enrollment of 3,286.46 By the end of the 18th century there were still 195 parish schools in operation. There are several reasons for the drop in the number of parish schools: first, the general decline of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth; second, the idea of peasant education was new and was met with resistance by some members of the gentry (especially after Bishop Massalski's resignation (1777) from the Chairmanship of the Commission); and third, Bishop Massalski's resignation itself released pressure from the pastors to establish schools. There is evidence to indicate, nevertheless, that in areas where the parish schools remained, they not only increased their enrollments, but more and more gentry began sending their children to them. For example, in 1777 Pabaiskas had a 20/80 per cent distribution of gentry vs. peasant enrollment, while five years latter the distribution changed to 35/65 per cent, respectively.47 The acceptance of the parish school as a joint gentry/peasant/burgher educational institution furthered the cause of universal public education in Lithuania.

Lithuanian - Polish Commonwealth had no census of the population. Some determination can be made from comparisons of school enrollments in parish schools and parish census figures. From very fragmentary information we can speculate that approximately 45 per cent of the boys between the ages of 7 and 11 attended parish schools, while only 15 per cent of the girls were in attendance.48 We must of course add to these percentages the number of children attending other types of schools (i.e. middle and higher).It would be extremely difficult to determine the percentage of all children attending parish schools, since the

Private Boarding Schools

The Educational Commission had under its control not only the ex-Jesuit schools and schools of other religious orders, but also private schools. These schools for the most part were boarding schools. On November 2,1774, Adam Czartoryski was assigned the preparation of the regulations governing these schools. On March 24, 1775 these regulations were submitted and approved.49 The Educational Commission's Regulations for Boarding Schools and Teachers 50 defined in great detail the operation and curriculum for these schools. All individuals operating boarding schools had to file requests with the Educational Commission for permission to operate. Schools found operating without permission were fined 1000 gulden. Persons operating these schools, once granted permission, had to file a monthly report. Every teacher employed by a boarding school had to present his qualifications to the Educational Commission for approval, as well as undergo an examination given by the district school in whose district the boarding school was located. This examination was administered by the district inspector. All boarding schools had to maintain a school library in accordance with a published list of library books. Boarding schools were required to teach Polish, French, and German languages, arithmetic, music and dancing.

Middle Schools

The Regulation for District Schools, prepared by Ignacy Potocki, was adopted by the Educational Commission on June 20, 1774.51 It basically was a collection of instructions on teaching methods and curriculum outlines to be used by all schools until appropriate textbooks were published by the Educational Commission. The introduction deals with teaching methodology, while the body of the Regulation is devoted to curricular requirements in the fields of Mathematics, Moral Education, Grammar, Logic, Rhetoric-Speech, Poetry, Metaphysics, Physics-Chemistry, History, Geography, Religion, Writing, and Composition.

The Regulation for District Schools was supplemented with a series of directives.52 These were: Rules for School Prefects, Rules for School Directors, and Rules for School Rectors. They defined administrative responsibilities of all school officials and the methods by which these officials were to enforce the regulations of the Educational Commission. Instructions for School Inspectors (Wizytatorow) included detailed forms to be used in the evaluation of teaching and administrative personnel. The internal evaluation system required reports from rectors regarding teachers, prefects regarding directors, and teachers regarding pupils. The rector's evaluation form included such items as teacher's health, his suitability for the job, his performance and dedication, and personal habits. The Educational Commission was very serious about school reforms and the implementation of its directives. For example, in 1783 two district schools were closed for not following curricular directives of the Commission. In 1784 two more schools were closed for similiar reasons.53

The methodological commentary in the

introduction to the Regulation

for District Schools reflects the same modern outlook on

education as do the regulations dealing with elementary education. The

Educational Commission explicitly emphasized that the curriculum in the

entire school system should be uniform and that teachers must follow

higher directives and suggestions. Apparently such a strong stand was

necessary to make it clear that the old Jesuit pedagogy was no longer

acceptable and that teachers now must follow the directives of the

Educational Commission.

According to the Educational Commission the educative process could be

carried on at an optimal level only when the student was healthy and

realized his goal in life and the benefits of a dilligent pursuit of

knowledge. Teachers were instructed to direct all their efforts to

produce humanistic, righteous, responsible, and charitable characters

and intelligent, sensitive, and productive members of the nation and

the church. Teachers were to improve their teaching methodology and

subject competence through extensive reading, study, and contemplation.

They were not to teach what they themselves did not fully comprehend.

Students' questions were to be answered courteously and in general

student inquisitiveness was to be encouraged. Teachers were to foster

paternal friendship with students, act as impartial judges in student

disputes, mete out disciplinary punishment in a measured and just

manner.

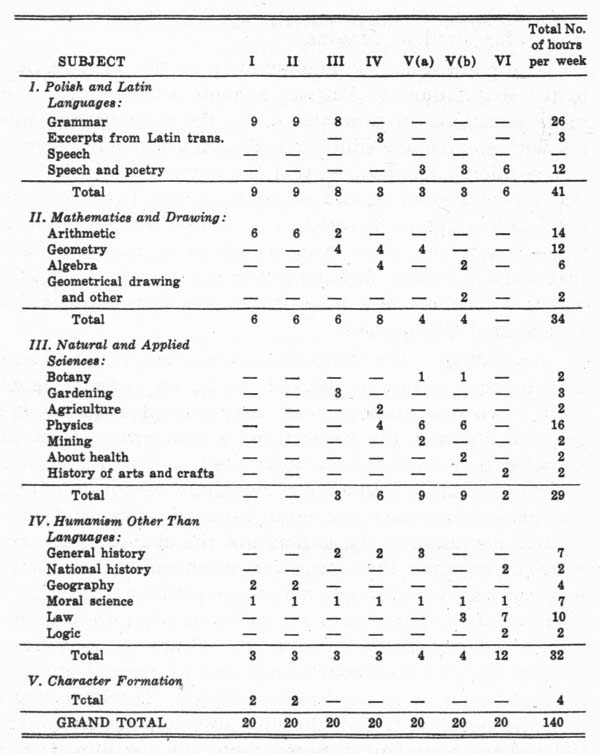

The curriculum of the chief district

schools is outlined in Tables 2 and 3. The curriculum of the chief

district schools and the ordinary district schools was only slightly

different. The program of studies at the chief district schools took

seven years while the district schools provided for a six-year program.

In the district schools the first two classes (4 years) were devoted to

general subjects, while the third class (5-6 years) was devoted to

specialized subjects. Each district school had only three teachers,

while each chief district school had six (one teacher taught both years

of the fifth class).

TABLE 2

PROGRAM OF STUDIES FOB CHIEF DISTRICT SCHOOLS OUTLINED IN THE DISTRICT SCHOOL REGULATION PUBLISHED ON JUNE 20 1774

|

Class |

FIRST SCHOOL CLASS |

SECOND SCHOOL CLASS |

THIRD SCHOOL CLASS |

|||

|

School Yea* |

First Year |

Second Year |

Third Year |

Fourth Year |

Fifth Yr. (2 yrs) |

Sixth Year |

|

No. of Instructors |

one |

one |

one |

one |

one |

one |

|

General Classes held daily for all students |

Arithmetic, Moral Educ. |

Arithmetic, Beg. Algebra, Moral Educ. |

Geometry, Moral Educ. |

Trigonometry, Common Law |

Higher Geometry, Economics |

Mechanics, Political Law |

|

Specific Subjects provided |

Latin and Polish |

Latin, |

Logic, Rhetoric, Reading of Classical Authors, Application of logic to life. |

Metaphysics, Poetry, reading of various classical authors |

General Physics |

Special Physics |

|

Classes on Tuesday and Thursday only |

History and Geography of Poland-Lithuania Intro, to Agriculture |

Contemporary History and Geography of Europe, Agriculture |

Ancient History and Geography, Animal Husbandry, and Zoology |

Natural |

Astronomical |

Geometry Astronomy Natural History |

|

Supervised Activities in Student Housing |

Character Development, Counting, and Corrective Instruction |

Translation of Authors, discussion of problems, and Corrective Instruction |

Discussion and clarification of questionable facts, Corrective Instruction |

Discussion and clarification of questionable facts f Corrective Instruction |

Discussion and clarification of questionable facts, Corrective Instruction |

Discussion and clarification of questionable facts, Corrective Instruction |

|

Religious Subjects on Sundays and Holidays only |

Catechism, Reading of the 4th Epistle |

History of the New and Old Testament |

Deliver Sermons in Church on moral issues and problems |

Deliver Sermons in Church on moral issues and problems |

Deliver Sermons in Church on moral issues and problems |

Deliver Sermons in Church on moral issues and problems |

|

Monthly Examinations |

Examinations for all subjects |

Examinations for all subjects |

Examinations for all subjects |

Examinations for all subjects |

Examinations for all subjects |

Examinations for all subjects |

SOURCE: Translation of original document "Porzadek i Uklad Nauk w Szkolach Wojewodzkich," as reproduced by Z. Kukulski, Przeptsy Pedagogiezne Komisji Edokacaeji Narodowej z lat 1773-1776 (Lublin: Sklad Glowny w Ksiegarni m. Arct, 1923),

PROGRAM OF STUDIES FOR THE CHIEF DISTRICT SCHOOLS AS OUTLINED IN THE STATUTES OF THE EDUCATIONAL COMMISSION OF 1783

SOURCE: Nellie Apanasewicz, "The National Education Com-mision of Poland 1773-1794," Education Around the World (U. S. Office of Education), April 8, 1960, p. 3. Translated by Miss Apanasewicz from: S. Krzeminski, Komissya Edukacyjna (Warsaw: Nakladem i Drukiem M. Arcta, 1908), pp. 92-93.

REPRINTED WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR

The program of studies for the chief district schools, as outlined in Table 2, provided for activities during the entire week. This was possible, since the students lived in student housing. Extra-curricular activities were organized by the school and included work on agricultural projects, training in speech, and student delivery of sermons in church on Sundays and Holidays.

New programs of study were established by the Statutes of the Educational Commission of 1783. In substance they were not different from those presented in Table 2. The new program of studies provided for a timetable specifying the number of hours each subject was to be taught (see Table 3). Under language instruction the new regulations provided division of classes to-.provide for beginning, intermediate, and advanced students. In general the curricula^ plans of the Educational Commission were progressive in their scope and depth and could be compared favorably with those of German, Swiss, French and American plans operant through the nineteenth century. The total number of hours of instruction reflected in Table 3 does not take into account the non-formal learning experiences students were required to engage as part of their total school program.

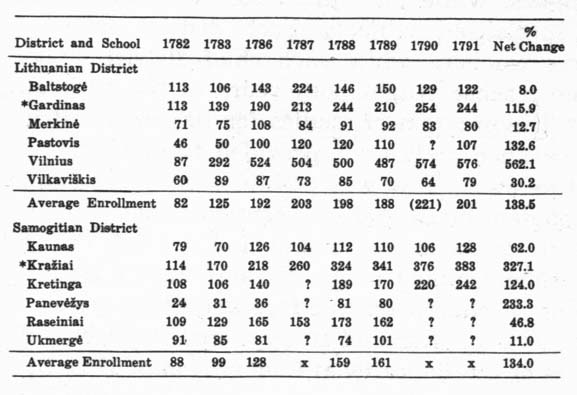

In the Grand Duchy of Lithuania the Educational Commission operated up to 38 district schools. Complete enrollment figures are available for about half of the district schools. As Table 4 indicates, the size of enrollment varied considerably, as did the rate of increase during the period 1782 - 1791. The largest enrollment and growth which took place in the Vilnius district school can be attributed to the proximity of the Academy of Vilnius and to the belief that attendance at the Vilnius district school would assure admission to the Academy. In schools shown in Table 4 an overall growth in enrollment for the entire period of 52.5 per cent is indicated. The growth rate of enrollment seems to reach a peak by 1786 and stabilizes thereafter. The effects on enrollment by the Partition of 1792 are not evident from available data. Examination of district schools on the Partition borders of 1792 did not reveal any trends.

TABLE 4

ENROLLMENTS OF SELECTED DISTRICT SCHOOLS IN THE ETHNOGRAPHIC LITHUANIAN EDUCATIONAL DISTRICTS, 1782 — 1791

NOTE: Chief District Schools indicated by asterisk.

SOURCE: Based on information found in "Lietuvos Mokyklos Istorijos Apybraiža— 14," Tarybinis Mokytojas (Vilnius), No. 2, January 8, 1969, p. 3 and A. Šidlauskas. "Vidurinės Mokyklos Lietuvoje XVIII a. Pabaigoje," in Iš Lietuvių Kultūros Istorijos, Vol. IV. (Vilnius: Lietuvos TSR Mokslų Akademijai Istorijos Institutas, Leidykla "Mintis," 1964), pp. 129-130.

The Educational Commission, a firm advocate of universal education,

opened middle school education for the peasants and the burghers. Even

though the majority of students attending the district schools were

from the gentry, a significant percentage were non-gentry. For example,

the Gardinas Chief District School's original class lists, in the

University of Vilnius Archives, show that in 1782 of the 218 pupils

attending, 22 per cent were non-gentry. The Minsk District School, on

the other hand, shows only a 10 per cent non-gentry enrollment. In

Samogitia, the Kretinga District School had a higher number of

non-gentry vs. gentry students, while the Raseiniai District School had

many peasant pupils, who could not even afford to pay for their

textbooks.54

Social class tensions in the schools were evident in the various

inspection reports on the district schools. It must be noted that some

gentry did not send their children to the schools operated by the

Educationa Commission, but rather employed private tutors for home

instruction. The Rector of the Schola

Princeps (Academy of Vilnius) M. Počobuta in numerous

letters confirms that many graduates of the Academy were employed by

the gentry as tutors. This may explain some of the gentry/non-gentry

enrollment figures in the district schools, but nevertheless, social

class barriers were broken.

The middle school reforms initiated by the Educational Commission had a lasting effect on the educational systems of both Lithuania and Poland. For the first time many non-gentry children were given the opportunity to pursue an education in many respects equivalent to that received by the gentry. Children of the gentry as well as those of the peasants attended the same schools. Curriculum reforms of the middle schools were in line with the latest educational theories and practices.

Teacher Training

While new parish and middle schools were being established, many members of the Jesuit Order left the teaching profession and thus, the teacher shortage became acute. On December 24, 1774, Bishop Massalski suggested to the Educational Commission that a Teacher Training Institute be established. The Educational Commission the same day approved this suggestion and authorized Bishop Massalski to open a school in Vilnius. On April 1, 1775, the Teacher Training Institute was opened.55 Its main goal was the education of primary teachers. The curriculum consisted of catechism, rhetorical reading, writing, bookkeeping, botany, surveying, and principles of agriculture. The student teachers were also taught singing and organ playing, so that they could act as organists in the parish churches.

The Educational Commission provided 25,000 gulden for the operation of the Institute (this was an average of 833 gulden per pupil). During the first year the Institute had 16. students, in 1776 the number rose to 30. In 1776 due to Bishop Massalski's various financial problems, especially with the Distributing Commission, the Educational Commission failed to make an appropriation for the Institute's operation. Bishop Massalski, in order to keep the Institute functioning provided funds from his own sources. Finally the Educational Commission reestablished the funds and set up a 14,000 gulden budget for the Institute's operation.56

Bishop Massalski's operation and planning of the Institute reflected his emphasis on education of the peasant class. The vast majority of students were from the lower social classes. Bishop Massalski believed that in order to be successful in teaching at the elementary level, where the majority of students were from the peasant class, the teacher also should come from the lower class. This would permit greater identification with the problems experienced by the peasants.

The Institute was officially closed in 1780. Upon its closing the responsibility for teacher training was trans-fered to the Academy of Vilnius. In 1783 Professor J. Stroinowski, of the Faculty of Law at the Academy, was given the responsibility of continuing teacher education at the Academy. Teacher training continued at the Academy of Vilnius until 1797.

As a result of teacher training efforts begun in 1775, the Educational Commission was able to change the composition of teaching staffs in the schools from 100 per cent religious in 1773-4 to 52 per cent lay teachers in 1792-1793.57

Higher Education — The Academy of Vilnius

With the authorization of the Sejm the Educational Commission took under its control and adminstration the University of Cracow and the Academy of Vilnius (Academia Vilnensis). The original intention of the Educational Commission was to convert these two universities into teacher-training institutions for the schools of Lithuania and Poland. This intention was not only realized, but was surpassed. These institutions, under the control of the Educational Commission, developed their instructional program, increased their faculties, fostered research, and opened new vistas of study. They remained universities in the full meaning of the term and comparable to any European university.

In November of 1773 the King requested that Joachim Chreptowicz and Adam Czartoryski direct a letter in his name to the Rector of the Academy of Vilnius, indicating the King's displeasure with the dissolution of the Jesuit Order and requesting that the Jesuits maintain the Academy in status quo, continuing teaching and administrative duties until new directives were received.58 It is interesting to note that the Chairman of the Educational Commission Bishop Massalski was also the Chancellor of the Academy of Vilnius from 1762-1773, so that administratively little change occurred.59 The Distributing Commission listed the property of the Academy from the announcement of the Bull on November 12, 1773, to January 13, 1774. The Educational Commission appointed a new Rector, Professor of Theology, I. Žaba. He accomplished little during his rectorship, which lasted until 1779. In 1779 J. Chreptowicz appointed Professor of Astronomy Martynas Počobutas as Rector. Počobutas served in that capacity from 1780 to 1799.

During the period 1773-1781 the Educational Commission was able to establish at the Academy a Collegium Medicum and lay the foundation for architectural studies.60 The Commission provided both the Academy and the University of Cracow 100,000 to 150,000 gulden per year for normal operations, as well as special appropriations as the need arose.

In 1781 the Educational Commission reorganized the Academy of Vilnius. On November 24, 1781, during a very impressive ceremony, the name of the Academy was changed to Schola Princeps Magni Ducatus Lithuaniae. The Academy maintained this name until 1797.61

The new Schola Princeps was reorganized into two faculties or colleges: Collegium Morale and Collegium Phisicum. The Collegium Phisicum taught such subjects as astronomy, higher mathematics, physics, chemistry, natural sciences, medicine, arithmetic, geometry, and mechanics. The Collegium Morale taught dogmatic and moral theology, scripture, church history, cannon law, common law, Roman law, world history, rhetoric, and literature. The already established Collegium Medicinae did not become a seperate college or faculty, but was a sub-division of the Collegium Phisicum.62

The administration of the Schola Princeps was composed of the Rector, the Chairman of the Collegium Morale, and the Chairman of the Collegium Phisicum. Since one of the principle duties of the Schola Princeps was the supervision of the Educational Districts of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and more directly the four Chief District Schools, the Schola Princeps had an administrative body established for this purpose. The Senate of the Schola Princeps was the responsible body for all matters dealing with organization, finances, and general administration of lower schools. The Senate was composed of the Rector, the two chairman, and all full professors.63 The Schola Princeps also had school inspectors, who visited the schools, and reported to the Rector on a regular basis the status of the schools in each educational district. The Schola Princeps in turn was directly responsible to the Educational Commission. Along with the administration of the lower schools the Schola Princeps was also required by the Commission to organize scholarly research and disseminate results of studies to the public.

Under the leadership of M. Pocobutas the Schola Princeps made major improvements. A new observatory was built in 1788, equipped with the latest astronomical equipment, purchased in London. The Collegium Medicum had a full staff of medical experts and operated clinics. The faculties of Physics, Botony, Biology, Zoology, and Chemistry became known for their work throughout Europe, attracting scholars like John A. G. Forster. Faculties of Art, Architecture, Philosophy and Law all made outstanding contributions. The groundwork was layed for the first Agricultural College in Europe, which was established in 1803.

The work of the Schola Princeps made a great contribution to the cultural life in Lithuania. With its forward looking Rector, the Schola Princeps allowed the University of Vilnius (named in 1803) to become the center of intellectual life until its abolition in the 1830's. Many of the graduates of the University of Vilnius became the outstanding leaders in the resistance against russification of Lithuania after the final partition in 1795. The University also produced such famous poets as Adam Mickiewicz. The rejuvenation of the University of Kiev was accomplished by professors trained at the Schola Princeps, and students who graduated from the middle schools of the Educational Commission. The influences and accomplishments of the Schola Princeps and later the University of Vilnius were wide and varied.

Society for Elementary Books

During the 37th meeting of the Educational Commission on May 13, 1774, Ignacy Potocki suggested that the Commission estalish a special society to improve teaching and textbooks in the schools.64 Acting on this suggestion the Educational Commission on February 10, 1775, approved the establishment of the Society for Elementary Books (Pol: Towarzystwa do Ksiag Elementarnych). The first meeting of the Society took place on March 1, 1775.65

Ignacy Potocki, Adam Czartoryski, and Andrėj Zamoyski were appointed members of the Society by the Educational Commission. They in turn elected eight additional members: Phlederer, Adam Jakukiewicz, Anto-ni Poplawski, Grzegorz Kniazewicz, Grzegorz Piramowicz, Jan Albertrandi, Kazimierz Narbutt, and Stefan Hollowczyc.66 The Society's main purpose was to commission authors to write textbooks for the new curriculum being introduced by the Educational Commission.

The Society for Elementary Books was under the able leadership and control of Ignacy Potocki, Secretary of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Potocki, a man of only twenty-three, was a product of Koniarski's Piarist reformed schools. Potocki, assisted by Grzegorz Piramowicz, the Secretary of the Society, and other eminent scholars like Antoni Poplawski and Jan Albertrandi, managed practically all of the Commission's pedagogic activities.

One of the first items on the Society's agenda was the publication of a regulation specifying the books the Society was planning to publish and lists of authorized textbooks for present use.67 Next, the Society sponsored an international textbook writing competition in such fields as logic, physics, mathematics, and natural history, in order to acquire the best possible texts for publication.68

The textbook competition was a great success. By March of 1776 the Society received many manuscripts; in the field of mathematics alone the Society received 13 entries.69 These came not only from Lithuanian and Polish authors, but also from authors all over Europe. The manuscripts were carefully scrutinized by committee members. Extreme care was taken to make sure that textbooks met the needs of the Lithuanian-Polish schools, had real life applicability, and were geared to the appropriate educational levels of students. Publishing costs had to he taken into consideration, so that costs of books published would not be prohibitive. Textbooks had to be clear, concise, and educationally sound. Proposed manuscripts judged to be the best were then commissioned to be completed and published.

Some of the best texts were those of S. Bonot de Condillac, who wrote the textbook for the study of Logic; S. Liuilier, of Geneva, Switzerland wrote the textbooks for Arithmetic, Geometry and Algebra; J. H. Hube who wrote the textbook for Physics; and K. Kliukas the textbooks for Botany and Zoology.70 Of the original 14 texts the Society set out to publish eight were already in use by 1792. Areas not covered by new textbooks had new texts already under preparation.

The Society did not limit itself to the publication of books, but also provided teaching materials, models, measuring instruments and the like.

The final meeting of the Society for Elementary Books took place on April 19, 1792. The Confederation of Targowica (17®), which began to transform the joint Educational Commission, disbanded the Society.71 The Lithuanian Educational Commission, operating under Russsian domination after the Third Partition (1795) until the Russian educational reforms of 1803, was unable to publish any new books.

END OF THE EDUCATIONAL COMMISSION

The end of the Educational Commission

corresponds

to the final fall of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The

Confederation of Targowicz during 1792-1794 disrupted the work of the

Educational Commission. The Gardinas Sejm in 1793 greatly limited the

Educational Commission's power. In its revision of the Statutes of the Educational

Commission the

Sejm transfered its control of the Educational Commission to the

Permament Council (this was not the original Permanent Council

established in 1772). The Sejm's action was influenced by the presence

of Russian military forces, who had entered the Gardinas Sejm and

forced the senators to approve all suggestions presented.72

For the Educational Commission the reduced power was a death blow. The

Commission was now required to send all of its plans and proposals to

one of the "ministries" under the Permanent Council for approval. The

Sejm in its action also removed from the Educational Commission the

control of private schools.

With the Third Partition of 1795, Lithuania was annexed completly to

Imperial Russia. With this annexation all Lithuanian governmental units

ceased to exist. With Russian approval a Lithuanian Educational

Commission was established in 1795. The activities and organization of

this Lithuanian Commission were officially approved by the Czarist

Government on July 7, 1797. The Chairman of this Commission was Bishop

of Vilnius J. Krasauskas. The Lithuanian Educational Commission

continued in one form or another until the Russian Educational Reforms

of 1803. Recent studies of the Russian Reforms of 1803 indicate that

they were based completly on the Statutes

of the Educational Commission of Poland and Lithuania.74

The Academy of Vilnius, through the Educational Commission, was the

guiding light for Moscow and Petersburg in Western educational and

scientific advances.75

Thus, the Educational Commission of Poland and Lithuania, the first governmental unit to achieve national educational administration and reform, ended its existence, but its reforms, regulations, curricular changes, and Statutes, continued in force under different governments and names.

The darkest days of Lithuanian educational history began with the final Partition of 1795. Within three decades the Russians began closing all schools in the country, forbade the use of the Latin alphabet, and initiated one of the most comprehensive russification programs. The ability of the Lithuanian nation to resist rested largely on the achievements of the Educational Commission.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The Commission for National Education of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania initiated educational reforms throughout the Commonwealth. Education was standardized and curriculum changed at all levels in accordance with published regulations. The concept of universal education was introduced and carried beyond the limits of acceptability determined by the still "feudal" thought of the nobility. Under the Educational Commission education became detached from the Church. Curriculum was developed for the moral, intellectual, and physical education of youth. The teaching body was secularized and given a status of high respect and position within the national society. A national hierarchy of schools was established which included all schools public and private from the elementary level to the university. Education of girls was not only provided, but required. Textbooks reflecting the new curricular changes were written for the schools by such men as Abbe de Condillac.

The Statutes of the Educational Commission published in 1783 layed the basis for educational planning and reform in the Russian Empire. The work of the Commission predated any attempt by other European nations at the establishment and operation of a national system of education. The Third Partition of 1795 incorporated Lithuania into the Russian Empire, and thus ended the official work of the Commission

Sources describing the work of the Educational Commission are limited mainly to the Polish and Lithuanian languages, sources in English, French, or German are virtually non-existent. Mr. Boswell in his evaluation of the Educational Commission's work states: "In the first place, the work of the Commission may be said to have been maintained in one region, namely, Lithuania, where the University of Vilnius blossomed out in great splendour after the fall of Poland, and became a centre of intellectual life..."

The Educational Commission's work and reforms need close examination and evaluation, for it does have a definite place in European educational history. Some of the questions that still need close examination are:

1. What role did Rousseau's Considerations sur le Gouvernement de Pologne (1772) play in the establishment and work of the Educational Commission?

2. To what extent did the writings of Helvetius (De l'Esprit — 1758 and De l'Homme — 1772), Rolland (Plan d'Education and Report on Education to Parliament — 1768), and La Chalotais (Essai d'éducation nationale — 1763) have on the organizational and curricular reforms of the Educational Commission.

3. To what extent, if any, did Condorcet have contact with

the Educational Commission of Poland and Lithuania, since his Rapport et Projet de Decret sur l'Organisation de l'Instruction Publique (1792) has striking similarities with the organizational structure of the Commission.

4. Were Russian educational reforms of 1803 based

almost entirely (as some authors claim) on the Statutes of the

Educational Commission vs. Condorcet's Rapport?

5. Did Pierre Samuel Dupont de Nemours, who was the Foreign

Correspondence Secretary for the Educational Commission, on his return

to Paris and high government positions, bring back with him the tried

ideas of educational reform?

Notes:

1 The following histories of education have been used for a

general background of 18th century education in Europe: Edward H.

Reisner, Nationalism and

Education Since 1789: A Social and Political History of Modern Education

(New York: The MacMillan Company, 1927); Ellwood P. Cubberley, The History of Education:

Educational Practice and Progress Considered as a Phase of the

Development and Spread of Western Civilization (Boston:

Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920); Hugh M. Pollard, Pioneers of Popular Education:

1760-1850 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press,

1957); Gabriel Compayre, The

History of Pedagogy, trans. W. H. Payne (Boston: D. C.

Heath and Company, 1901); Henry Barnard, National Education in Europe

(2nd ed; New York: Charles B. Norton, 1854).

2 See, for example, the following works:

J. Lewicki, Ustawodawstwo

Szkolne za Czasow Komisji Edukacji Narodowej (Cracow:

1925); Z. Kukulski, Pierwiastkowe

Przepisy Pedagogiczne Komisji Edukacji Narodowej z lat 1773-1776

(Lublin: 1923); S. Lempicki, Epoka

Wielkiej Reformy (Lwow: 1923); T. Wierzbowski, Komisja Edukacji Narodowej i jej

szkoly w Koronie 1773-1791, (Warsaw: 1901-1917); S. Kot, Gcneza Komisji Edukacji

Narodowej „Sprawozdania Akademii Umiejetnosci"

(Cracow University: 1919); J. Lewicki, Geneza Komisji Edukacji

Narodowej : Studium Historyczne (Warsaw: 1923); S. Tync, Nauka Moralna w Szkolach

Komisji Edukacji Narodowej (Cracow: 1922); T. Wierzbowski,