Editors of this issue: Antanas Klimas, Ignas K.Skrupskelis

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 17, No.1 - Spring 1971

Editors of this issue: Antanas Klimas, Ignas K.Skrupskelis Copyright © 1971 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

|

A JOURNEY INTO THE SUBCONSCIOUS

LEONAS URBONAS

On entering the world, man at birth brings with him his own death, and his life is a chain of efforts to avoid it. With every breath and heartbeat, the human body renews the struggle with death. Should this struggle be successful, man would live forever. In the depths of his being this is what he thirsts and strives for.

Death is a product of consciousness, and consciousness is death's only victim. Death, as man relates himself to it, does not exist in the evolution of life. Man, being concerned and aware of himself, selects a fragment from the manifestation of life and magnifies it into a monstrous all-consuming image called death. The image separates conscious energy from access to the cosmic energy (or mind). The separation is death. Death is not a life-destroying force, nor is it life's counterpart. It is the evidence of life. It enables evolution. Man created death and therefore it is in his power to dissolve it.

Through evolution man can grasp life as truth. Through all its forms, life is revealed as an indisputable possibility. On the road of evolution it was inevitable that in due succession, consciousness would be born. Man became aware of himself. First the awareness could be only vague and short-sighted. Through this shortsightedness, man created the concept of the individual. Misreading the significance of the forces surrounding him, man acted in fear. Fear strengthened the concept of individuality; individuality strengthened death and the fear of it.

Although through fear, man separated himself from access to cosmic energy, he never loses that feeling of being part of an immortal "something" behind the dark wall of death. He never ceases searching for a way out of his individual shell into the mainstream of the life force. Being a leaf, he wants to be the tree. Being a small creek, yearns to become the ocean. Being created he wants to be the creator. He feels he is all of them, only the lack of "awareness" separates him. Guided by this deep-seated feeling, he learns to create. He begins to create himself into a being more able, more aware of himself and the surroundings in which he lives. As a tangible result of this, Science and Art are evolving.

After thousands of years or erratic zigzags in his progress, man today can celebrate a few successful steps on his long road towards immortality. He has no doubt that he is finding his way towards a greater knowledge of things, towards better health, in turn, more life. He is aware that this is only a beginning. Deep down in himself he yearns for an unceasing flow of consciousness, of vitality that never ebbs away; for immortality.

It could be that Science and Art, no matter how trustworthy they appear to us now, may be only temporary vehicles on the lengthy road of evolution. Life has been through many stages, has acquired and discarded many forms. Spiritual evolution is only beginning. It is not too bold to assume that it will also go through many forms, use many more vehicles. Science and Art as we know them today, may not lead man to the gates of immortality. Not even the total dissolution of the concept of individuality will return man to the complete awareness of cosmic energies. Using many vehicles like Science and Art, acquiring and discarding them at the right time, man may become brilliant of mind and vision.

This would enable the mind to invert and return through itself to the beginning of consciousness and even further down the evolutionary column of all life forms. The return journey to the beginning of the evolutionary adventure could provide an understanding of the purpose or the willingness of cosmic energy to initiate this cycle in which man, at present, can see neither very far back nor much ahead.

To become immortal the mind must be able to move in both directions. It must understand the processes and complete the cycle by its own efforts. Lack of awareness separates man from his life source. Ignorance is the fuel of death. Knowledge and vision could remove that fuel. There would be no death as man knows it. Man could keep on creating spontaneously. At man's present stage, I cannot see any kind of consciousness or "soul" being able to live on without a physical body. The theory of a division between body and soul is a type of "wishful thinking" and inhibits the evolution of man. Action that stems from illusion cannot have long-lasting results. Man's involvement in Art and Science, liberating him from self-centeredness, carves new steps towards a higher awareness and abundance of life. This is not "wishful thinking." .It is a fact, or rather, a sequence of facts. Science and Art, though evolving along different channels are heading in the same direction and complement each other. Through large and small contributions by individuals or groups of scientists, science grows into an immense colossus. It is possible for a scientist to add his life's contribution without fully comprehending its total vastness.

The artist today is aware that in his endeavor he is creating not only a work of art but also transforming himself. He also realizes that the existence and the potential of a work of art is relative to the creative powers of the artist and the spectator. It is essential for an artist to comprehend, to experience the whole art movement. To be an artist, one must become art; to create art one has to live art. If at this stage of evolution, man's powers of awareness are so limited that his spiritual existence is locked away in a prison cell, then the artist is only a prisoner with occasional absences of leave. In those moments of creative ecstasy the artist celebrates his temporary liberation from the cell of individuality by stepping consciously or unconsciously onto the path leading toward the light of immortality, or cosmic energy. These excursions from the prison of the mind make the artist a different person, at least for a short time. Every artist who experiences this, wishes these excursions to be available more frequently and of longer duration.

The spectator, with his eye fixed on the constantly growing wealth and diversity of the works of art, and not participating so much in the observation of the evolution of the creative mind of the artist, finds himself more and more confused. The developing artist has to come early to the realization of the essence of that which surrounds him. In other words, he must experience the action of the mind in relation to the environment. He must see the mind in action while it is "making" the environment. Only then, the fact that a work of art without a spectator does not exist, comes to him with its full impact, transforming the entire outlook and philosophy of the artist. The transformation affects his set of values, and in turn, the distribution and flow of creative energies.

Such an experience, some years ago, transformed my attitude toward creative activities. It also affected my total view on life in general. During my hours of creative work the center of attention began to shift from the painting to the painter. Introspection became more important than judgment of the painting. When I realized that the work of art is almost as accidental in its powers of stimulation as any other object not created by man, my sole purpose was to know the artist himself. This discovery finally allowed me enough detachment to begin a journey into the sub-conscious. To invert oneself, to return into deeper levels of one's consciousness simply by sensing subtle and fleeting threads of one's thoughts and feelings, is a most rewarding experience, though difficult to come by. It is like a journey into an immensely large unknown city, at the wheel of an unfamiliar vehicles, with no maps or compass, through streets and crossroads with no signposts. One is trying to find one's way to the center, and one would like to observe and enjoy the views while traveling. If possible, of course, to reconstruct the adventure later on, in a way understandable to others.

The journey began with a gigantic roll of paper, that somebody had given me. At first it did not attract me. It stood forgotten in the corner of the studio for some months. One day, from the manufacturers, I received a selection of large sample jars of paint to experiment with. It was then that my eyes turned to that great roll of paper. A roll with thousands of sheets in it... Cut it! Spoil it, if you so please. With no feeling of responsibility towards the materials, in a mood free from obligation, like a child, I started to paint, or rather to "doodle." Here was liberty to try anything; harmonies or disharmonies of colors and rhythms; brushes of various sizes and fibers, in search of unusual effects and textures. This "doodling" became my regular refreshment after so-called "serious" work (paintings of much larger size). Often I could not stop for hours, in pursuit of very next consequence of every new attempt on each page. This occupation became nearly an obsession with me until no "serious" work was being done at all.

The result of this type of painting did not interest me as much as the actual doing of it. I did not bother to study it; at least not for some time. Occasional glimpses into the growing heap of painted pages revealed some motifs and textures that had never before appeared in my work. Yet I felt no temptation to treasure these pictorial inventions, or to make use of them to enrich my larger works. I was more interested in going on. I was becoming interested in facing situations where pictorial problems appeared and solutions came to mind. With time, the solutions came to mind easier and faster. I was aware that this had a lot to do with the fact that I had unlimited reserves of material for these trials. The liberty I thus had was changing the direction of involvement. The desire to produce a work of art diminished, giving way to an emerging interest in observing the creative powers at work, and in turn, to finding out ways to facilitate the flow of creative energy. The fervor of experimentation captivated me completely. I cut pages off the roll by the hundreds. I painted, not caring if I spoiled them, nor did I worry about the passage of time. All I cared for was to follow the visions and images as fast as they appeared, to turn as they turned, to recognize the creative impulses, and not to be ruled by any doubt as to the value of what I was doing. If the impulse was to repeat a motif, again and again, I did so until the impulse lost its power. I worked long hours with short breaks in between for food and drink; or in long continuous stretches, up to twenty hours at a time. It was interesting to experience different moods and degrees of alertness, by working at different room temperatures and various times of day or night.

One year passed. The paper roll shrank considerably, and the stack of paint-covered pages mounted. I painted these pages, putting them aside without stopping to study them. At times I was tempted to take a second look at them, but in those moments, some deep-seated feeling prevented me from chancing an indulgence into any critique or appreciation of them. I tried to listen only to the most spontaneous impulses. It became less and less difficult to sort out contradicting or conflicting impulses from those which were guiding ones. One becomes aware with time, that for every mood or mental attitude, there is a certain state of tension or relaxation in the body. Learning to observe and respond to physical sensations in the body, one can acquire greater control of the mind. I found it possible to will oneself into a creative trance-like state, which I would liken to the riding of a fast moving wave. One wants to learn how to stay in it as long as possible, to learn to feel those invisible edges in order to move position and stay in the center of the wave.

I tried not to contradict, nor to force the urge to paint. The easier the previous flow of creativity and technical skill, the sooner and stronger came the next wave of creativity. It could come at any time of the day. Little rest or sleep was necessary, three or four hours to regain physical energy was sufficient. There was no feeling of nervousness or mental exhaustion; on the contrary, prolonged creatively active hours rewarded me with a feeling of well-being and achievement, with overtones of curiosity and eagerness for the next day. With relaxation there is a feeling of well-being and a tingling sensation on the face. Colors appear incredibly beautiful and clear. The experience of beauty itself is strikingly different from our ordinary daily state of mind. During such trance, man is most fully awake. It felt as if I lived in two different worlds, and both of them were very real. One of the main differences between them was the awareness of time. While painting, time ceased to exist; the flow of five or fifteen hours felt the same.

Eventually the time came when the desire to paint faded and I wanted to examine the stack of paintings. Leafing through them, I found considerable amount that I could not remember having painted. I knew the paint, the "handwriting" was mine, but the existence of them as paintings was a surprise to me. These paintings were "forgotten" works. Only by the location in the pile could I relate them to the other works. The fact was clear, the paintings were "forgotten," but why or how had this happened? I was puzzled but not concerned in any way. Time would solve the matter I trusted. Then the urge returned, and I went back to painting again. For almost another year I continued the experiment, and found that more and more its activity was shifting in emphasis, until it was centered on the artist himself and less on the painting. The series of paintings that resulted I named "Cycle 'A'."

I was beginning to realize that I was working in a trance-like state while painting, that I reached a level where daily reality diminished, and I passed a barrier that separated the memory from more conscious levels of the mind. It was evident that this was happening on numerous occasions. The realization revitalized my interest in going on. I wanted to find out, to decipher the mechanism that was responsible for this. There was only one way by observation. What faced me was namely: to observe myself at work and at thought, not forgetting that the observer and the observed are one and the same entity... I knew that conscious observation had to be very subtle and should never run ahead or influence the creative flow and action. It was not important to me whether what I was doing was new, or had already been explored by others. I knew I was standing on the threshold of something that was new to me. I was also aware that I had crossed this threshold and wanted to understand how it was done.

The dream of every artist is that he have intense vision, fast and clear-cut decisions at work, and an inventive mind that helps those visions to be technically transferred into reality. This ideal state of mind is seldom attained and sustained.

What really does prevent or help creativity? The answer can only be found within oneself. One has to know oneself, not only the conscious, but also the deeper sub-conscious levels of the mind. One has to journey into oneself. It is like folding back all that is alert, intelligent, intuitive and creative on that which is constantly becoming automatic or self-triggering. The conscious mind has a very limited spotlight on itself; its dimension is shallow. By returning to deeper levels of being, the mind expands in a spherical dimension and at the same time augmenting prophetic and visionary phenomena. Most people spend their lives on one level, or in one dimension of the mind. They are entrapped by their set of values. These people therefore have very little creative urge or capacity. Their set of values has been handed down to them by parents and educators. It concerns their daily activities, fitting into the frame called "society." It demands all their energy, and sometimes more than they can give.

The distributor or man's energy is his "set of values." The average man's set of values is rigid; he defends them when they are threatened, sometimes at the price of his life. Man is still defending values that are based on nothing more than the sound or a word. Probably man is at a very critical point of evolution where he is rapidly losing access to his instincts and yet has very little to hold on to. His powers of awareness are limited. But the set of values of a man whose powers of awareness are more highly developed, are far more complex and constantly in the process of revision and change. Consequently, moods and attitudes change and therefore the flow of creative energy changes also. One cannot exist without any values at all. Liberating oneself from one attachment or value, one directs energy and attention to something else, something new. By revising our involvements, we may reduce the intensity of the attachment. One cannot say that one's daily problems do not exist they do and ignoring them wont help. More profit is to be gained by revising, rearranging them so that they burn up less energy, which is necessary to amplify the visions emerging from the deeper levels of consciousness, that are usually lost in the noise of distracting daily thoughts and worries. One has to learn to still the noise in one's own head.

To break the pattern of thought, to see oneself in unpredicted environments, such things as "happenings" are organized. Sounds and colors are used to raise the tolerance level to extremes in an attempt to awaken latent potentials, to expand the limitations of individual awareness. Man is ever restless in his shell. He is trying to free himself, and there are two ways: either by going out of his mind, or going down into it. By going into it, it is possible to arrive at a point where thought takes its first shape. The greatest part of our thinking is in the form of word-phrases or "verbalizing." It can be guided by "purpose" or allowed to simply "idle" in the form of free association. The flow of this association depends on the degree of awakedness. Closer to sleep, thoughts begin to mingle with images. Journeying into the deeper levels of consciousness, one has to understand the mechanism of thought-energy to be able to dissolve the verbalization before it takes form.

Rational or purposeful thinking already has its direction and aim. Obviously, the process carries its negative side too. It is, in a way, a dialogue within oneself. The energy is divided into two contradicting movements. Once decision is reached, the energy is free to work. With the next problem, the process repeats itself. With conflict work ceases.

Verbal thought, with its linear and time dimension, inhibits abstract vision, which, by its nature, is able to move through all dimensions. Verbal thought leans heavily on concepts like past, present, future; good or bad; behind, ahead; above, below. This brings dualism and restricts the mind to moving only on the level of relative values, and actions based on comparisons. To seek a state of so-called "blank-mindedness" by ignoring or trying to suppress verbal thought, is nonsensical. The mind is never blank, not even in sleep. However, it is possible to slow down thought, to gain insight into the patterns that perpetuate associations of thought and then virtually to "unhook" the energy. Tremendous alertness is necessary to come to the point between two thoughts, to recognize the stillness of the moment and to direct energy into this stillness, enabling a state of mind which is alert, but not busy. It is like breaking a sound barrier. Those who have experienced this will agree that there is an extraordinary feeling of well-being, with so much energy on hand that is not directed nor self-involved. There is no urge to accomplish anything. One feels being creative without creating. There is an awareness that is not personal nor based on gratitude for achievement, accomplishment or recognition. It is a joy, not a pleasure; a source of self realization and revitalization for the artist.

I can see primitive man, way back before the dawning of civilization, in moments when secure from environmental threats, because his mind was uncluttered by thousands of words and symbols, and not being concerned with busy conscious thoughts, could have felt himself in similar creative state of mind and awareness. I sense that this awareness has deeper roots going back to older forms of life than man. I feel that here is the key leading towards complete understanding of how cosmic energy, which is ceaselessly in flux, created living cells, and through millions of years, succeeded inscribing notes of cosmic music into each cell. These musical notes enable "awareness" to come into being. Awareness of different degrees. Primitive stages of awareness were not foreign to man because he passed through them to become what he is now. There are ways to experience this again, even for brief moments. Often we watch the graceful gliding of a seagull and wonder how they learn this without spoken or written words, without assistance of instructors or educators. Yet, they do. The notes written into living cells of every being, play incredibly sensitive music to which the animal responds and acts spontaneously. This we call "instinct."

In the world around us, there are many more "garments" our consciousness has outgrown and discarded with time; but, remains of them are still felt within us. They can be re-discovered in silent meditation when long forgotten visions and images come in strength before the "inner" eye, and one attempts to recapture and give them shape and form on canvas. In my art, I tried to recapture this from memory, but failed there was a lack of creative spontaneity. I yearned to paint in the trance-like state of active meditation... but, painting is action full of vitality consuming one's energy. How would this then be possible? How could one paint in a trance? If not for that great roll of paper and ensuing Cycle "A" experiments, the answers to these questions would not have been found. This experiment also brought to light the fact that man separated himself from the greatest part of his mental capacities by a thin wall of doubts and uncertainties.

Action that follows a pattern is not creative. To-be creative is to liberate oneself from a pattern. One has to break the pattern in order to remain creative. There must be patterns to be broken. Once the pattern of meditation was broken, I found out that this trance-like state of being takes place not only in a state of physical stillness, but also during creative activity. I wanted to find the source of this energy to return from every creative "trip" of the subconscious with small pieces of puzzles and reconstruct the mystery in the light of the conscious mind. While painting and doodling so freely, yet, so eagerly, it was almost inevitable to develop good technique. Use of the palette became nearly as automatic as breathing or walking.

Vision without conflicting rationalization, grows into a wave of integrated action. One movement initiates the next. Past, present and future begin to reverberate. The mind is free to move back and forth, because it is not confused and tied by time of obligation. It becomes action that has no obligation to correct its previous action, only to fulfill. It is almost impossible to make a mistake when creating, though misleading thoughts or images do appear, bringing a "warning signal'" with them. The hand stops near the painting. There is an uneasy feeling. If not obeyed instantly, the trance will fade into a sensation similar to nausea. The creative trance is a state of great alertness and sensitivity. Decisions are made and images recognized and evaluated with tremendous speed. It is so because the mind engages the more-automatic centers of the brain for this action. The less-automatic centers act as observers. The subconscious spontaneously and prophetically judges when the painting is completed, or, in other words, when it reaches its highest state of aesthetical stimulation.

The eye scans the painting but the mind does not offer any further suggestions to continue. At the same time, the hand refuses to touch the painting. There is joy of achievement. This can happen at any time after the beginning; in an hour, ten minutes or even after a few initial strokes. If the warning signal is not heeded, creative inspiration gives way to a feeling of lethargy. To remain in a state of inspiration is comparable to fire-walking, remaining watchful, alert, subtle and firm, without the slightest doubt tainting the mind.

What happens when the artist's mind recognizes that the painting is completed? At that instant, the creative energy expresses itself in the ecstasy of joy and admiration. The mind begins to absorb the painting and to inspect the cause of aesthetical stimulus. The painting becomes evidence of achievement. Achievement reveals the creator's potentials, offers new possibilities; on the other hand, it impedes the fulfillment of consequent attempts. In order to remain creative, one has to denounce and detract oneself from his achievement. It is a contradictory situation, rich in movement and most rewarding if understood and handled properly. The greater the achievement, the greater the elation and joy. It revitalizes the brain centers and with the echo of the past experience, the artist is enticed into reproducing its course rather than creating a new one. The urge to create finally starts to sort out the conflicting elements and makes them work creatively. When the wave of joy reaches its height and before it transforms into solely pleasurable admiration, the mind comes up with a will-full suggestion to "forget" it. One feels it is best to attempt total disassociation with the work of art, to relax and start anew.

It is almost inevitable that motives of the previous painting will haunt the memory and consequently influence one to begin the next composition under strong influence of previous motive. Lack of detail in the memory calls for inventiveness, thus returning the artist to creative action. It became obvious to me that the cause of those "forgotten" paintings lay in the moment of unconscious willful suggestion during the trance-like state. A motif may provide inspiration and stimulus for several attempts with slight variations in color and composition. When all possibilities are explored, the motif becomes dull and boring. There is a state of non-creativity and dilemma. There are two ways to solve this: either by ceasing painting or allowing the feeling of dissatisfaction to build to a rupturing tension which will eventually lead to invention of a new motif. When this happens, an uneasy load weighs on the chest. There is a feeling of annoyance and irritation. Yet one continues until again, the hand with the brush stops. The painting is finished. There is no joy of appreciation. The brush reaches for a jar of rich paint and almost violently splurges across the painting. Dullness suddenly turns into eruption and excitement. One senses energy working in several directions simultaneously condemnation, destruction and creation. The mind experiences all at once. The relationship between old and new textures in the painting creates tensions having the capacity to stimulate the spectator creatively.

For the artist, these explosive moments are very significant. While established patterns are being torn down, the unknown comes into being. It marks the birth of a new work of art. With its overtones of agony, it is symbolic of the evolutionary steps of mankind. The movement may not be more than a brushstroke, yet it is like a cliff near the ocean, revealing many layers which can help to gain insight into the underlying working forces. The arrival of new motifs comes in waves. The initial crudeness gradually becomes more skillfully handled and technically polished. As soon as one feels there is no more call for ingenuity or inventiveness, longing for the next movement begins to build up. Those "forgotten" paintings were mostly from the middle of the wave, when discovery was still fresh and technical skill to handle were well matched.

After two years with Cycle "A", I felt the approach of the end of experimentation and inquiry. As unintentionally as it started, Cycle "A" was not begun to prove anything, nor systematized in advance. If so, it would have defeated itself. One step anticipated the next one. The only principle was to have no principle. It means complete freedom which led to crossing barriers of doubts, opening paths of creative energies never before experienced; creative energies within the reach of every man willing to make the effort to inquire into and understand the workings of this complex mechanism inherent in us all.

However, I feel that this is not the end. With greater and concerted effort, it is possible to reach even deeper subconscious levels of the mind. In my experience, when vision and action were spontaneous and fully integrated, the process of painting was not fully automatic. The use of subtle conscious control was sensed at certain points of the movement, as when one deepens or widens a stream in order to help it flow downhill more smoothly. Does not man spend most of his life digging and deepening grooves, in the hope that his stream of life will flow more smoothly and directly towards the source of life itself of cosmic energy?

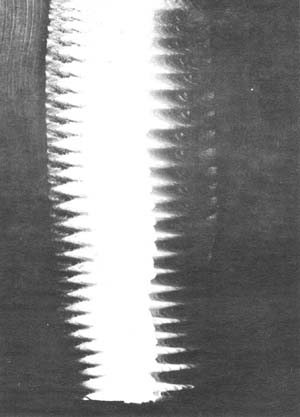

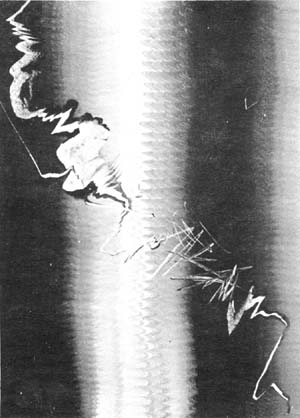

No. 1. Basic motif which dominates many compositions in Cycle "A".

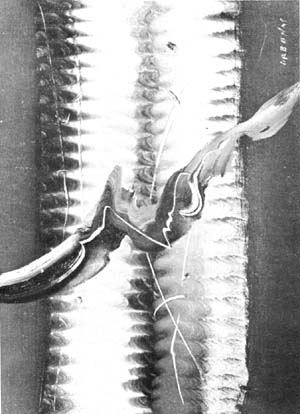

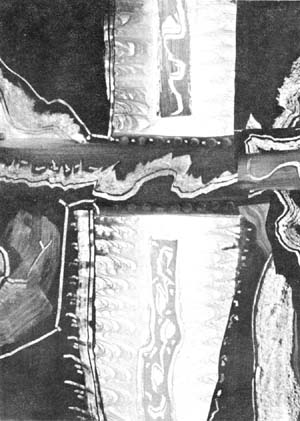

No. 2. A new motif appears; it dominates the first plane. The basic motif becomes the background.

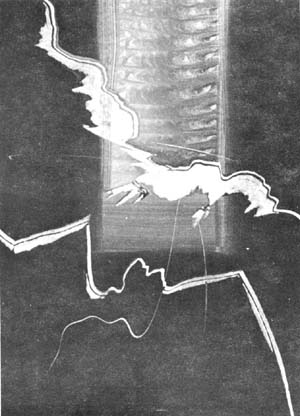

No. 3. A modification of the basic motif and of the new motif.

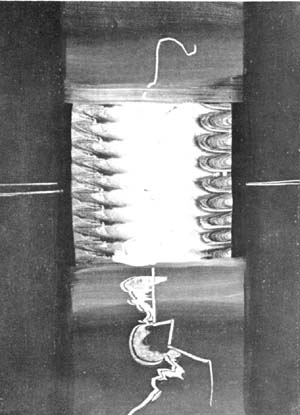

No. 4. Another modification of both motifs.

No. 5. Exploration of further possibilities of the same motifs in different forms and colors.

No. 6. Exploration of further possibilities of the same motifs in different forms and colors.

No. 7. Exploration of further possibilities of the same motifs in different forms and colors.

No. 8. Exploration of further possibilities of the same motifs in different forms and colors.