Editors of this issue: Thomas Remeikis

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 18, No.4 - Winter 1972

Editors of this issue: Thomas Remeikis Copyright © 1972 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

|

THE UNITY OF MULTIPLICITY IN THE PAINTINGS OF KAZYS VARNELIS

HAROLD HAYDON*

University of Chicago

The world is fortunate to have Kazys Varnelis among its artists. No doubt there are a few others like him, totally dedicated to their art, working quietly and long. Although the spotlight turns on them occasionally in an exhibition, or an article like this, they do not work for recognition and honors. Instead, they work for the sake of art and the contribution they can make as creative artists to the world's heritage.

Fortunately, Kazys Varnelis has not gone unnoticed in Chicago, his adopted city. In 1970 he had a major exhibition of paintings in Chicago's Museum of Contemporary Art, and in 1971 - 72 examples of his work were circulated throughout Illinois by the Illinois Arts Council. Before that he exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago in the 1967, 1969, and 1971 biennial exhibitions by artists of Chicago and vicinity, winning the Vielehr award in 1969. Looking ahead, Varnelis is preparing a one-man show for the prestigious Milwaukee Art Center in 1973, and another in the same year at the Akron, Ohio, Institute of Fine Arts.

As the paintings reproduced on these pages reveal at once, Varnelis' art is out of the ordinary. His standing among world artists may be judged by the inclusion of his work in "Galerie der Neuen Kunste," a book by Heiz Ohff published in Berlin in 1971 that is an international survey of three hundred avant garde artists.

Although Varnelis had been nourished by much 20th century abstraction, beginning with Cubism as an early inspiration, he now has perfected a personal style embodied in paintings of very high quality and technical excellence. While there are aspects of his work that are traditional and conservative, it also is truly contemporary in being conceived in modular form and by inviting a special kind of participation on the part of those who view it. I shall return to these matters later.

But first it is important to consider the origins of the artist Kazys Varnelis was born in Alsėdžiai, Lithuania, in 1917, and came to maturity between Europe's great wars. Auspiciously in 1941, the year of his graduation from the Institute of Fine Arts in Kaunas, he was made Instructor at the Institute. From 1941 to 1943 he also served as Director of the Museum for Ecclesiastical Art in Kaunas. But the disruption of the times made it necessary to give up these posts, and, making his way to Vienna in 1943, Varnelis entered the Academy of Fine Arts there, receiving his degree in painting in 1945. For the next several years he traveled in Europe and then came to the United States, where he established his own stained glass studio in Chicago in 1951, a business that sustained him until 1963 when he turned his energies entirely to painting.

Writing in the Canadian art journal "Artscanada," for the October - November, 1971, issue, in an article entitled "The Modular Monochromes of Kazys Varnelis," the distinguished Dutch art historian and museum director Jan van der Marck called attention to two elements in Varnelis' paintings that reflect his national origins. One is the abstract decorative quality also found in Lithuanian folk art woodcarving, which the artist knew as a child in the work of his father, a self-taught carver of crucifixes and church interiors. The second, more abstruse, element, van der Marck identifies as structural complexity related to "the verbal and syntactical complexities of the Lithuanian language, which is archaic, rich in synonyms and diminutives."

The reflections of these ingrained and nearly unconscious predispositions can be found in all of Varnelis' mature work, now made up largely of paintings. In his Chicago home, visitors en route to his top floor studio pass through a room of his abstract sculpture, silent and mysteriously suffused in blue light. The simplified planes of these sculptures carry over into optical complexities of repetitive continuity, parallelism, and reversal in the paintings that fill the upstairs studio and now compel the artist to devote additional space in his home to his work, especially since the most recent paintings are scaled to museum walls and large architectural settings.

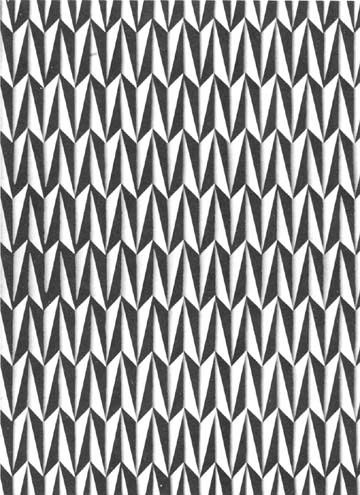

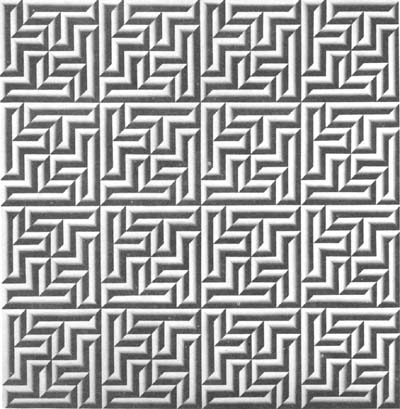

In the 1968 painting titled "Variations," and in "Sixteen Times Four" of 1970, one can almost imagine the slanting planes of chip-carving, all of equal depth and co-existing in the shallow three-dimensional space of a typically 20th century picture plane. To translate the black and white reproductions of these and other paintings by Varnelis, and to imagine them as they appear when confronted directly, one must know that they are painted with brushes so subtly controlled that no brush marks mar the soft transition from light to dark. The planes so painted may appear to be flat or, alternatively, to be curved surfaces, bulging or hollowed out, and each way of seeing is legitimate and intended. One also must think of the paintings as essentially monochromatic, in cool grays, soft greens, deep blues, muted reds, and occasionally a combination of two subdued hues. Within these self-imposed limitations of hue, Varnelis achieves a full range of color, in the sense of subtlety and variety of tones.

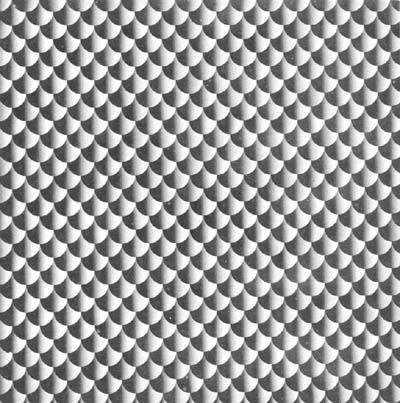

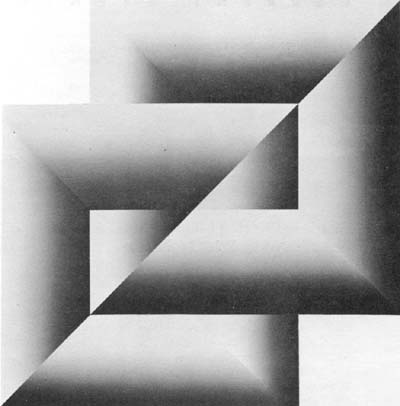

Furthermore, the viewer must be prepared for sudden, involuntary reversals of the painted forms. Looking at "Convex Plus Concave," painted in 1971, one may see it first as cup-like depressions, and then, with a lightning reversal, as a field of rounded forms. Or the sequence may be the other way around, first the egg and then the cup. The painting is neither one nor the other, but both, as its title indicates.

In this duality of form the viewer becomes an active participant in the experience of art. It is intriguing to attempt to control the reversals that seem to operate under laws of their own. While all works of art may be said to live many different lives, depending upon what viewers bring to them, Varnelis ensures a unique kind of relationship between his paintings and all who see them because the paintings have this capacity for unpredictable reversals of space relations. They stem from a kind of optical illusion rarely exploited in the fine arts Albers and Escher have done so and they have none of the disturbing optical razzle-dazzle associated with Op art. One can enjoy Varnelis' paintings as living things, catching them in their various states out of the corner of one's eye as well as when giving them full attention.

Like all authentic artists, Varnelis is fundamentally conservative. He requires a firm traditional base as a starting point for his inventions, no matter how free, even willful, his results may seem. No doubt, his academic training in Kaunas and Vienna provided this traditional bias which shows up in his initial conceptions for paintings. Always, he says, he imagines the light falling from the upper left, a convention that is old in Western art and in all probability comes from right-handed scribes writing from left to right. The monks in their cells, copying books on vellum, must have seated themselves so that light from their windows and candles fell from the left. Another traditional aspect of Western art appears in the symmetry and unity of Varnelis' compositions. The designs complement and complete themselves in ways that could be extremely static were it not for the always imminent reversals of space relations.

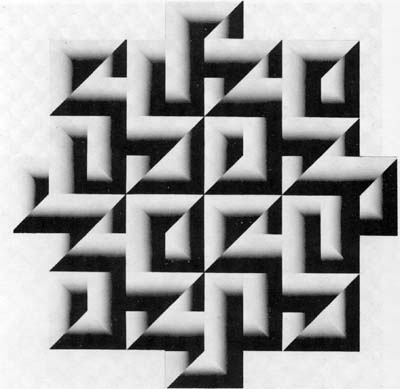

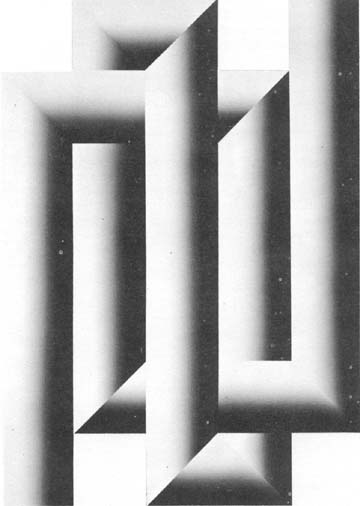

During the past several years there have been important developments in Varnelis' art that extend without contradicting his basic premises. In earlier works he accepted the traditional rectangular canvas for his paintings, which often were square. Recently, he has created "shaped" canvases, including long narrow ones, with edges corresponding to their individual design units. Whereas the units of design in "Variations" and "Convex Plus Concave" are cut off uncompleted at the edges of the canvas, and the sixteen squares of interlocking T' in "Sixteen Times Four" might also be continued indefinitely on all sides, such recent shaped canvases as "Message" of 1971, and "Polygon," "Duplex," "Mono-rhythm?" and "Status Quo," all of 1972, are complete in themselves in more or less symmetrical fashion. "Message" "Polygon," and "Monorhythm" are quite symmetrical. The other two are less so, with "Status Quo" bearing a title that may be a misnomer, since it is a new departure, the open-ended figure.

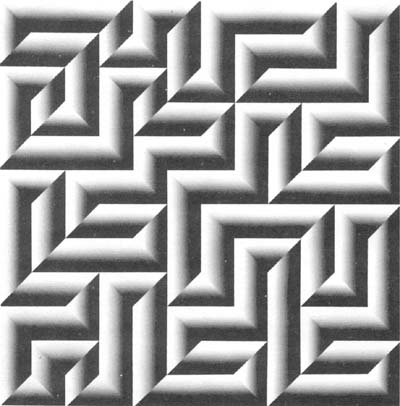

As one can perceive immediately, Varnelis' initial disposition was toward unitary designs that could be repeated endlessly. Even when they are complex, as "Pseudo-Labyrinth" is complex, they complete themselves, with the movement of volumes always returning to the point of beginning. "Status Quo," on the other hand, differs in having ends that lead into, or out of, the interwoven figure. The incomplete square, "Monorhythm," may be considered transitional, since the cut off ends tempt the eye to bridge the gap, creating a certain amount of tension in this otherwise relatively simple figure.

Anyone who traces "Pseudo-Labyrinth" from beginning to beginning, and who may start anywhere because it is an endless, continuous passage, will discover an inconsistency in the logic of Varnelis' lighting of form. While it is true that "right side up" can be determined for all these paintings by finding the one corner where the light appears to fall from above and left on a convex form, Varnelis' inclination to place a light edge against a dark edge whenever possible within the total scheme of illumination involves him in certain inconsistencies which have a lot to do with the space reversals. There is always something irrational about art that has enduring interest, and this logical inconsistency in Varnelis' work contributes significantly to its power to fascinate, as forms shift from convex to concave, from projecting corners to corners receding.

With all his extensive training and experience in art, Kazys Varnelis' unique talents were not fully recognized until the last few years of exhibition successes. While the reasons for this, no doubt, are complex, and involved to some extent with the maturation of the artist, it is true also that the times have caught up with him. Modular elements corresponding to his repetitive modules, are increasingly evident in the modern world. From the practical and aesthetic modules of contemporary architecture to the duplicate objects manufactured by the millions for everyday use, the unity of multiplicity is very much a fact of life today, and it is time for reevaluation of what an earlier time would have regarded as monotony in the extreme.

Kazys Varnelis has shown in his paintings how infinitely variable the simplest module can be. His art, outstanding by itself, can help everyone find life-sustaining variety in the mechanical repetitiousness found everywhere today.

* Harold Haydon is Professor of Art and Director of the Midway Studios of the Department of Art, the University of Chicago.

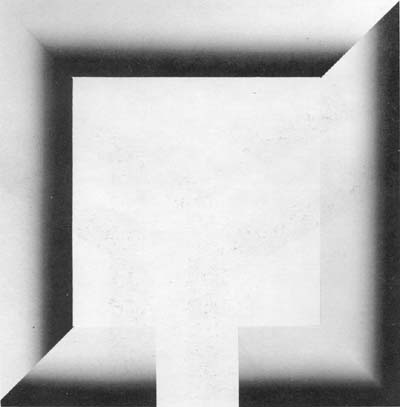

Kazys Varnelis, "VARIATIONS", 1968, acrylic on canvas, 78"x60"

Kazys Varnelis, "SIXTEEN TIMES FOUR", 1970, acrylic on canvas, 78"x78".

Kazys Varnelis, "CONVEX PLUS CONCAVE", 1971, acrylic on canvas, 68"x68".

Kazys Varnelis, "POLYGON", 1972, acrylic on canvas, 85"x85".

Kazys Varnelis, "MESSAGE", 1971, acrylic on canvas, 78"x68".

Kazys Varnelis, "MONORHYTHM", 1972, acrylic on canvas, 68"x68".

Kazys Varnelis, "DUPLEX", 1972, acrylic on canvas, 48"x48".

Kazys Varnelis, "PSEUDO LABYRINTH", 1969, acrylic on canvas, 78"x78".

Kazys Varnelis, "STATUS QUO", 1972, acrylic on canvas, 84"x60"