Editors of this issue: Thomas Remeikis

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 20, No.2 - Summer 1974

Editors of this issue: Thomas Remeikis Copyright © 1974 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

|

Charlotte Willard With an Essay by Waldemar George, ADOMAS GALDIKAS: A COLOR ODYSSEY, New York, October House Inc. 1973.

When Adomas Galdikas died in 1969 in New York, few knew the real artist behind this man of humble appearance who had fifty years of brilliant creativity. Through the unified effort of four Lithuanians the sculptor Aleksandra Kašuba, the poet Leonardas Andriekus, the photographer Vytautas Maželis, and the artist's wife and the art critic Charlotte Willard of October House Inc. in New York a monograph of the painter was published after three years of research and planning. The artist had for years dreamt of it but never expected it to become reality. The volume, consisting of 171 pages, 40 color plates, and 133 black and white illustrations, is introduced by Ms. Willard in 23 pages of text.

Charlotte Willard, a former Contributing Editor to Art in America, former art critic of the New York Post, and author of several art books, including Frank Lloyd Wright American Architect, Moses Soyer American Painter, What is a Masterpiece?, and Famous Modern Artists from Cézanne to Pop Art, had some hesitation undertaking this task. However, as the research proceeded under close consultation with Mrs. Kašubą, she became involved to a point where she not only interpreted the painter, but also the particular heritage from which he came.

The art critic gives a full account of the painter's life, with interviews of his friends and anecdotes that reveal his character, stressing his continuous drive to achieve the one ambition to be a painter of nature. Galdikas, born in Lithuania in 1893, is one of the initiators of modern Lithuanian art, succeeding the unique and mysterious figure of M. K. Čiurlionis with whom the true twentieth century art in Lithuania begins. Although he studied with the best masters at the Baron Stieglitz School of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg, Galdikas looked to nature in his native land, the impressionists in Copenhagen, and the Far Eastern art in Berlin for a further clarification of his search for artistic identity. He never became a true impressionist or expressionist, which was the vogue in Europe, but some traces of Bonnard can be seen in his "Color Odyssey," as the title so precisely implies. His pantheistic worship of nature allowed only rarely for human form, which strangely enough is a very prominent feature of most Lithuanian art. Man is always somewhere in the background, overshadowed by nature. There could be many reasons for such a viewpoint, including the ancient Lithuanian pagan religion, but Willard does not analyze the phenomenon in any detail.

It is difficult to grasp Galdikas' art in the 40 color reproductions. He has been a prolific painter and, unhappily for us, he never dated any of his work. It is therefore very difficult to follow with any precision the order in which they were painted. Some of the dating in this monograph is questionable. Galdikas was so careless about such details, that he sometimes didn't even bother to sign his temperas.

Charlotte Willard tries to find a place for Galdikas' art among the American abstract expressionists, and to make her point she gives a full page of art reviews printed in the American press and art magazines after his one man show in John Myer's Gallery in New York in 1954, and in Feigl Gallery in New York in 1956, 1957 and 1960. Ms. Willard writes: "Galdikas had already gone a long way down the same path. That his work developed independently and simultaneously with that of the great masters of Abstract Expressionism in the United States both vindicated his vision and obscured his contribution." (p. 32)

After a detailed biographical presentation, Ms. Willard finally gives her own evaluation of the artist (pp. 30-37). Of these, the first three pages are the best as far as the interpretation of Galdikas' art is concerned. Although the critic concentrates mainly on his late period, she tries to grasp his entire career. She carefully comments on the three main periods of the painter's work. The first period in Lithuania (1918-1944) covers 25 years of experimentation combined with the other duties of his life. As a teacher he prepared a whole generation of Lithuanian artists, such as Vytautas Kašuba, Telesforas Valius, Elena Urbaitis, and others. As an official government artist he designed Lithuanian stamps, bonds, and paper money. His originality and innovative ideas could be seen in the costumes and sets made for 19 stage productions. One of them, Šarūnas, won him a gold medal at the International Exposition in Paris, 1937. Ms. Willard comments on this period as follows: "Adomas Galdikas tried many avenues before he came upon his path. In his first efforts Galdikas was content to draw or paint nature as he felt it, after studying intensively the visual facts... His last painting in Lithuania, "Trees" (1943), leaves behind the stiff and rigid realism of his earlier pieces and already has the nebuluos impressionist quality that was to characterize his Freiburg series some years later", (p. 31)

The second period, the most productive and successful, was spent in exile in Germany and France following World War II and in New York. The art critic sums up this "Freiburg Period" as follows: "With exile from Lithuania, he turned to symbolism to deepen his meanings to paint the unseen in the seen. Crosses, trees, cemeteries, chapels, peasant huts, the skies become symbols of heaven and earth, of death and resurrection. He could never entirely abandon symbolism until the last year of his life..." (p. 31). Ms. Willard does not readily explain Galdikas' unique symbolism, which has nothing to do with the school known as such. The source of inspiration for the artist stems from the painting of his native land in all its seasons and, when that becomes too remote, from color alone, color that he looked for everywhere, including the TV set. It is true that Galdikas moved slowly from a "mimesis" of nature to a less mimetic painting of skies. His classical design of a road bursting into explosions of blossoming bushes and trees and an occasional human figure disappear in his last period. His attempt to find color expressionism emerges fully in 1964. Ms. Willard poetically summarizes it as follows: "The colors to which he seemed to dedicate the last years of his life seemed to be beyond violence, beyond beauty, beyond precise analysis. It was color that at last could portray the unity of his inner vision, and the outer world color that could speak of the speechless reveries of man, the silent vision of consciousness and its root in nature. In his final confrontation with color he arrived at a vibrant pretentious darkness the darkness that carries in it the seeds of light" (p. 36).

All in all, Ms. Willard's research on this eccentric artist, even though incomplete, is remarkable, particularly if we bear in mind that she never met him and relied purely on the testimony of others and very limited records.

The study, included at the end of this monograph, by the French art historian and critic Waldemar George, famous for his spirited nationalism, is from a different perspective. The French critic States that "Chagall, Soutine, Picasso, Gris, would never have attained universality had they not been exposed to the influence of French painting" (p. 159). I would dare ask what would have happened to the School of Paris without the contribution and talents of the above names, and many others like Modigliani, Brancusi, Dali, and Miró. Of course, nobody disputes that France has given the genius of Matisse, Bracque, Derain, Vlaminck, Dufy, etc. Waldemar George spends several pages writing of the French glories and finally settles on the Lithuanian artist for whom he has the greatest esteem: "Adomas Galdikas is to become her national painter. While he refuses to adopt the formulas of a lazy and senile regionalism, he acknowledges his destiny and his ethnic ties. He does this without constraint... His work records, beyond his own dreams and anxieties, the latent will and the desires too long repressed of a people who are returning to their sources in order to find their own path" (p. 162). It is curious to note that while African art played such an important role in the birth of modern art, the Lithuanians had their own primitive folk art that inspired many of their artists, particularly Galdikas, who "perceives the magic and mystery of his ancestral gods".

Waldemar George's interpretation of Galdikas is much more inspired and precise. He unquestionably understood the poetic mood behind Galdikas' Freiburg period: "Painter of the earth, Galdikas engages the trees in a dialogue, of which we find traces in many of his canvases and drawings. Like Corot and Theodore Rousseau, he knows their interior armature..." (p. 164). This essay, written in French in 1948, and translated and published here for the first time, is more appropriate for the front of this volume rather than as an appendix. While Charlotte Willard spends more time discussing the artist's last period and his personal life, Waldemar George, in his eight pages, gives a more complete analysis of the Freiburg period and only glances for a moment at the possibilities of abstract development, which, personally, I don't believe Galdikas ever fulfilled: "It remains to be seen whether Galdikas will slide into abstraction or whether he will renew contacts with objects" (p. 166). This is the question which is not answered in this monograph.

STASYS GOŠTAUTAS

Wellesley College

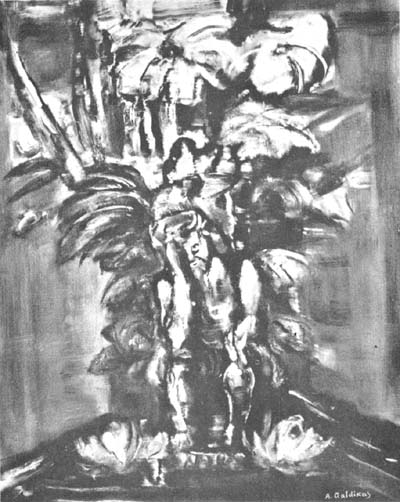

Adomas Galdikas, Still Life, New York 1952, oil on canvas (John Foster Dulles Collection).