Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas

Copyright © 1977 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 23, No.2 - Summer 1977

Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1977 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

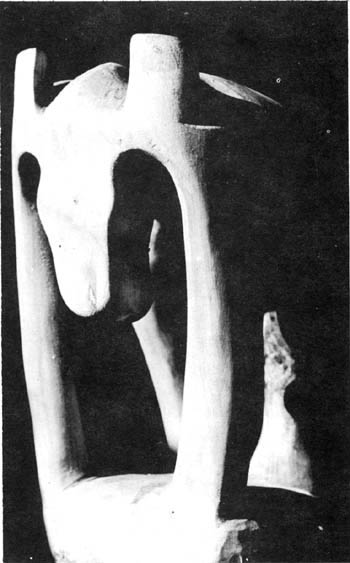

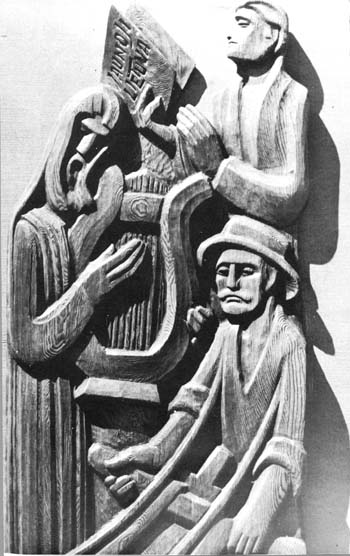

Quietly flow the melodies (Polyester), 1962

THE ART OF DAGYS

Jokūbas (Jacob) Dagys was born in Slepščiai, near Biržai, on 16 December, 1905. After graduating from the School of Art in Kaunas in 1932 he taught in a high school and took part in art exhibitions in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. In 1937 he furthered his art studies in Berlin and in Paris. After he left Lithuania in 1944, he lived for several years in Germany and in England. In 1951, he moved to Canada and has been living in Toronto. His work has been exhibited in Toronto, Montreal, Quebec, Ottawa, Chicago and other cities. Many of his compositions are in private collections. He works mainly in wood but sometimes he uses bronze and other materials. In 1967, Dr. Otto Scheid wrote of Dagys:*

In museums and exhibitions, one can always observe some people who, being different from the pictorially-minded majority, are attracted by sculpture. Indeed, those who primarily prefer the three-dimensional art, follow one of our older instincts, one that we share with animals. It is the sense of form and space and their correlation these rich aesthetical possibilities man has developed since diluvial times, prior to his earliest paintings.

From those cave dweller times until the generation that preceded us, the art of shaping forms along with counteracting spatial elements into expressive compositions went together with an inclination or an ability existing in humans only, not in animals, that of figurative creation. During about three hundred centuries, the two elements of sculptural experience were one. Both in barbaric and in classic civilizations, creative sculpture was an organic unity of natural figures with the expressiveness of form and space. In African, pre-Columbian, Indian, Chinese, and western medieval sculptures, the oneness of figure and composition is always present; it is not less inseparably united in those ancient Greek and later Italian or northern master works that we most admire.

The concept of the figure and the interrelation between it and form-space was never homogenous. Peoples, times and individuals richly diversified the elements of sculptural experience, coming close to nature or withdrawing from it into remote resemblance or even into rather symbolic analogy.

It was a deplorable privilege of our time to interrupt that tradition of all mankind by giving up figurativeness and proclaiming form or formlessness as the only principle of sculptural art. For Dagys, particularly at the time when he was a newcomer to the western hemisphere, it might have been a strong temptation to abandon his east-European devotion to beliefs and ideals and to buy cheap success through conformity. This would have meant to adopt not only the incomparable heritage of the West, but also its modern weakness, its unfaithfulness to its supreme values. The oeuvre in front of us bears witness to a strong character which enabled him to counteract the general impoverishment of contemporary sculpture and to enrich it by an original contribution.

While many artists are perpetually looking for motives, Dagys had rather to defend himself from the dangerous bounty of the motives that seem to pursue him. Among his moving forces are the echoes of a people's struggle for their living space and their freedom, all the Lithuanian remembrance, pre-Christian mythology and devoted Christian faith, his search for himself in a new environment, and, finally, the human feelings which are both reality and vision; there is love, heroism, farewell, despair, nostalgia, reconciliation. The dangers of literary concepts have to be overcome. In this struggle for pure sculpture, a highly-developed connection with the material was helpful. It was especially wood, the treatment of which shows fine, loving intimacy by which forming becomes a process analogous to man-woman relation in its never ending newness. So the power of the theme could be subordinated to the entirety of the composition. The material and the subject, the general form resulting from variable and always varied balance of mass, space and movement, and the governing idea become one unit. Thus in its best instances the art of Dagys achieves a quality relatively common with Eskimo or African carving or with the golden ages of European art, but in our time limited to very few artists who still possess the unspoiled primary instincts.

There is another quality of powerful masterpieces which is apparent in some of Dagys works. When he means a specific martyr, a hero of his people who is going to die or to be executed, the meaning is widely being enlarged. Without any additional action or attribute, it becomes generally human, detached from its particular story and background. So it is the very martyr; his suffering, his faith and his greatness are becoming our own. In his lovers, the old theme returns with the same convincing generality. And in the silent dialogue of a giant bull with a tiny child we feel most elementarily the power of primordial being in its mysterious necessity and goodness.

We ought to be aware of the relativity of any judgment on any contemporary. With this limitation, our conclusions about the art of Dagys could be summed up by one unrestrained recognition: His merit is his personal synthesis of faithfulness and originality, an approach to sculptural values that deserves to be called monumental.

In battle (Wood), 2968

Saturday night (Sketch in ink)

Quiet sunset (Bronze), 1965

Experience and youth (Wood), 1969

The wounded duke (Wood), 1974

Darkness spreads across the world (Wood), 1959

Road to the east ( Aluminum), I96I

A restful moment (Wood), 1975

A wanderer (Wood), 1964

The king dictates a letter (Wood), 1974

Down from the mountains (Marble) 1964

The sorrowful one (Wood), I965

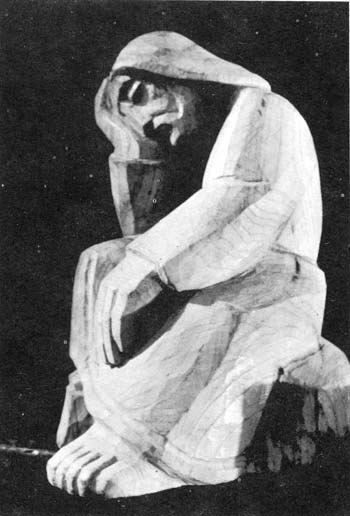

Homeless (Wood), 1975

Father was a soldier (Wood), 1976

Country Christ (Wood), 1976

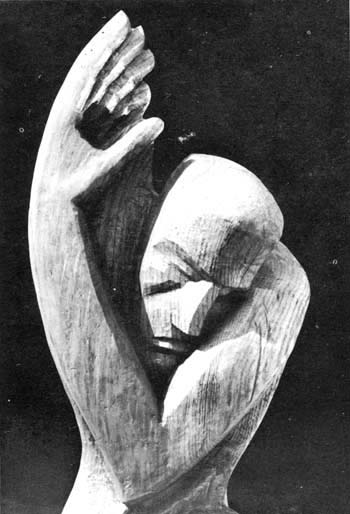

Everything is lost (Wood),1971

What a monster (Bronze), 1964

* Dagys Sculptures and Paintings, Introduction by Dr. Otto Schneid, Toronto, 1967, pp. 4, 5.