Editor of this issue: Saulius Kuprys

Copyright © 1977 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 23, No.3 - Fall 1977

Editor of this issue: Saulius Kuprys ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1977 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

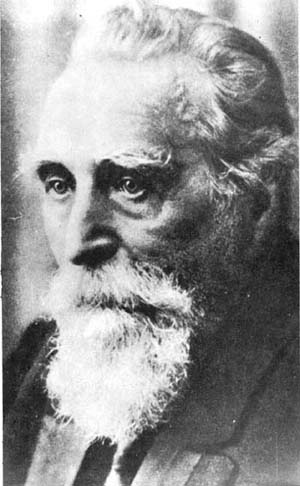

DR. JONAS BASANAVIČIUS FOUNDER OP AUŠRA

JONAS PUZINAS

|

|

DR. JONAS BASANAVIČIUS |

On February 16 of this year, we commemorate the 50th anniversary of the death of Dr. Jonas Basanavičius in Vilnius in 1927. He was known as the father of Lithuania's national rebirth. His work was so all-encompassing that it would be impossible to thoroughly cover all aspects of his productive life. It was Jonas Basanavičius, who rekindled the consciousness of the Lithuanian nation, founded the first truly Lithuanian-language newspaper, Aušra (The Dawn), who ardently fought for the freedom of his homeland. He was a folklorist, scientist, founder of the Lithuanian Scientific Society and its chairman until his death, and a noted physician. This article will deal with only one aspect of his lifehis contribution to the national rebirth of the Lithuanian nation.

Jonas Basanavičius was born in 1851 on November 22, in the village of Ožkabaliai, in a peasant household. In 1873, upon finishing Marijampolė high school, he entered Moscow university, where in 1879 he received a doctorate of medicine. Frorn 1880, he worked as a physician in Bulgaria, and later did postgraduate work in Prague and Vienna. After living abroad for 25 years, he returned to Lithuania in 1905. At this time, Basanavičius actively joined the cultural, social, and political life of Lithuania. He chaired the Great Assembly of Vilnius in 1905, fought for Lithuania's freedom during World War I> was a delegate to the Lithuanian Taryba (Council), and finally in 1918, on February 16, read the Declaration reestablishing an independent Lithuanian state. Afterwards, he resided in Vilnius, until his death.

What were the factors instrumental in the development of Basanavičius' national consciousness? Most likely his home village of Ožkabaliai, an area rich in folklore and historic sites, played a significant part. The area was known for its ancient mounds, which were the subject of numerous folk tales and legends, and fields strewn with archaeological finds. Jonas Basanavičius in his autobiography reveals the impact the local historic sites had had on him:

Together with tales about the crusaders, the mounds held a fascination for me since my earliest days. Close to Ožkabaliai, in the fields of Piliakalniai village stands a beautiful mound. Since my youth I had begun paying visits to this large and very beautiful mound, which brooding in an area of untold beauty and peacefulness, stands on the shore of Aista river. In my youth 1 heard tales of bewitched beautiful maidens imprisoned in the mound; the mound itself was supposedly piled up with hats and baskets. ... I later became acquainted with the Pajevonis mound, later yet with the Kaupiškis mound, near the Prussian border, and with the mounds at Rudamina, Lakynai, and others. On these hills, I can confidently assert, my Lithuanian consciousness was confirmed."1

At fourteen, in 1866, ]. Basanavičius entered the Marijampolė district school. At this time, he began to secretly read Lithuanian books. During his third year he became familiar with Donelaitis' Metai (The Seasons), Adam Mickiewicz's L Kondratowicz and other patriotic works. He was especially interested in Lithuanian history. In his autobiography, Basanavičius writes: "My first source on Lithuania's past was my father; the information centered on the feudal system of the area; later M. Stryjkowski's Kronika polska, litewska, žmodska (Krolewiec 1582) became my guide; Guagnini, Dlugosz, Kromer, and other chroniclers, and later J.J. Kraszewski's writings had influenced me greatly. While still in high school I was comfortably acquainted with Lithuania's history". 2 He also successfully studied Latin, Greek, became proficient in Russian, and also learned Polish.

When he arrived at the Moscow University, Basanavičius was a thoroughly committed Lithuanian. Here, he found a considerable number of Lithuanian students. Basanavičius later wrote: "we collected material, planned projects, and discussed ways in which we could revive our nation." Other Lithuanian students however "blew into a Polish horn," while other "well-to-do Lithuanians head over heels were the first to jump out of their Lithuanian skins."3 Basanavičius befriended Vincas Pietaris, author of the historical novel Algimantas, who like Basanavičius would later become a physician. Mikalojus Katkus, author of Balanos gadynė, who entered Moscow University in 1873, wrote that when he, Basanavičius, and Pietaris would meet, "We would discuss only Lithuanian matters and nothing else."4 According to Katkus, Basanavičius and Pietaris avoided any friendship with Polish students or polonized Lithuanians.

Upon completing his medical studies, Basanavičius left Russia. He believed he would have more freedom to work for the Lithuanian cause from abroad. He accepted an invitation of Dr. D. Molov, chairman of health services of the Bulgarian Internal Affairs ministry to practice in Bulgaria. In 1880, he was put in charge of a 50-bed hospital serving three districts. In addition, he maintained a private practice. He spent his free time on Lithuanian matters: he did research in ethnology and Lithuanian history, and wrote articles for Lithuanian publications published in Prussia, such as the Lietuviškas Ceitungas. When in 1882 for a short period he took up residence in Prague, he took the first steps toward publishing a Lithuanian-language newspaper aimed purely at the needs of LithuaniaAušra. In March of 1883 in Ragainė, in German-ruled Lithuania Minor, the first issue of Aušra was published. The newspaper, surreptitiously distributed in Russian-ruled Lithuania, played a major role in Lithuania's national rebirth. The political and social goals of Aušra were outlined in its first issue:5

1. Through the ages our nation had undergone such derision and subjugation, that one can only marvel that it is still in existence today.

2. In the olden days Lithuanians inhabited an area twice its present size; today Lithuania is but a shadow of the ancient state.

3. Today, enlightened men familiar with our life and its tribulations, unanimously state that those neighbors under whose yoke our people live, are determined that we, if not today then in a year or two, would become Germans or Slavs.

4. But we are people as good as our neighbors, and we desire to enjoy all the rights endowed to all mankind, just as our neighbors seek them for themselves.

5. Among these rights, the first one would be the right for Lithuanians in Lithuania to receive their learning and education in Lithuanian schools.

6. Today, we clearly see that foreign-language schools usually turn Lithuanians into foreigners.

7. We ourselves must concern ourselves with contemporary matters.

8. That which the schools do not offer us, we must attend to ourselves.

9. Our most important concern will be to inform our brother Lithuanians about the events of ancient times and the works of our honorable ancestors, whose works and whose love of our homeland we have forgottenwe ourselves do not know which parents' children and grandchildren we are.

10. If every good son respects his parents, and the parents of his parents, then we too, Lithuanians of today, should follow the good example set by the sons of ancient Lithuania.

11. Therefore, we must first know their ancient lifestyle, their nature, their ancient beliefstheir works, their concerns, their cares.

12. Understanding their lives, we will better understand them, and having understood them, we will understand ourselves."

These programmatic guidelines were adhered to: Lithuania's past was presented, romanticized, one might say worshipped. Through such a popularization of Lithuania's history, Basanavičius hoped to rekindle and strengthen Lithuania's national consciousness. Basanavičius concludes his article, "Apie senovės Lietuvos pilis" (On the Castles of Ancient Lithuania), with the following:

"If Lithuania lives today, it is only because of the strength of our honorable forefathers, and the hoary mounds. Let us concern ourselves in emulating our ancestors by always being true Lithuanians, loving our beleaguered land, our beloved language, and its cares."6

|

|

Title page of this first national Lithuanian newsapaper AUŠRA, issued in 1883. |

In the other articles the people were urged to maintain national unity, strengthen Lithuanian families, educate themselves, raise the country's economic welfare, take an interest in trades, and were also given medical advice.

Recently, a Czech historian M. Hroch, estimated that during the period between 1880 to 1885, before the appearance of Aušra and immediately afterwards, there were only 257 Lithuanian activists.8 Aušra alone had over 70 co-workers. At first, most of its supporters and contributors were students; later, it successfully attracted professionals and intellectualsphysicians, pharmacists, lawyers, engineers, and teachers. A majority of them were of rural stock.

One of the major concerns voiced in Aušra, was the demand that Russia again allow the Lithuanians to publish books in the Latin alphabet. However, the tone of Aušra, on this and other questions was not overly aggressive: the people were urged to avoid confrontations, not to issue demands, but to make requests. Aušra approached the situation idealistically: how could one ignore basic, universally accepted, human rights? The first issue of Aušra editorially express a hope that in connection with the coronation of tsar Alexander III, the ban on the press would be lifted. At the urging of Basanavičius and other activists, farmers from the Vilnius area approached the Russian authorities requesting permission "to print our books in the ancient manner." Dr. Basanavičius, using the pseudonym of Birštonas, called on the people to continue sending such requests, stating that "no one buys or reads" books in the Cyrillic alphabet and that "Lithuanian words cannot be written in Russian letters."

While Aušra, later edited by J. Šliupas, J. Mikšas, and M. Jankus, lasted for only three years, it nevertheless was able to enkindle the flame of Lithuania's national reawakening. For many of Lithuania's intelligentsia, Aušra was a decisive factor in their decision to join the effort for the re-establishment of Lithuania; e.g., Vincas Kudirka and Jonas Jablonskis. When Aušra ceased publication, other papers along ideological lines began appearing: in 1887 Šviesa (The Light), in 1889 Žemaičių ir Lietuvos Apžvalga (Samogitian and Lithuanian Review) and Varpas (The Bell), in 1896 Tėvynės Sargas (Guardian of the Homeland) and others. They were all published in Lithuania Minor and were smuggled across the border into Russian-ruled Lithuania. The publishing of such newspapers continued until the ban on the press was lifted on May 7, 1904. And on December 10, 1904, in Vilnius, the first legally published daily paper Vilniaus Žinios (Vilnius News) appeared.

One can imagine, with what satisfaction and gratification Basanavičius received the news of the first Lithuanian daily paper legally published and distributed in Lithuania. Therefore, on his return to Lithuania on August 1, 1905, he first visited the Gediminas Castle hill, and on the following day at the offices of Vilniaus Žinios visited with the paper's founder Petras Vileišis, and editors Jonas Kriaučiūnas and Kazys Puida.9

Lithuania's national rebirth, begun by Basanavičius and his compatriots, spread quickly; the number of Lithuanian intelligentsia increased appreciably. Varpas continued the tradition of striving for national unity established by Aušra.

While Aušra meekly reminded the people of the need to strive for their rights, idealistically believing that the ideals of human rights will win out in Lithuania as well as throughout the world for all of mankind, Varpas boldly pointed out the injustices perpetrated by the Russians and strongly denounced all policies of russification. A similar editorial line was followed by Tėvynės Sargas, edited by the Rev. Juozas Tumas-Vaižgantas.

At this time, a movement for the establishment of Lithuanian autonomy within its ethnographic borders developed. It was believed that this was the only realistically attainable form of self-rule possible in the current political climate. Thus, the Great Assembly of Vilnius, called in 1905 and in which Basanavičius played a major role, did not go beyond the question of national autonomy. However, during World War I it became clear that the national movement would not be satisfied with anything short of an independent Lithuanian state. This goal was finally achieved on February 16, 1918, when Basanavičius, as the eldest member of the Lithuanian Taryba read and signed the declaration reestablishing Lithuania's independence.

Following the reestablishment of the state of Lithuania, Basanavičius was able to devote more of his time to scientific work and to the development of the Lithuanian Scientific Society, which he had founded in 1907. Under Basanavičius' leadership, the society, during a twenty-year period, grew into a respectable scientific organization. Until it was dissolved in 1940, it had some 2,000 members. At its annual conferences, in addition to discussing organizational matters, lectures were presented in these fields: history, ethnography, linguistics, law, economics, geology, and music. It was on Basanavičius' suggestion that college-level courses began to be offered in 1919. During World War I, when a network of Lithuanian schools was being organized, the society published 56 textbooks. From its inception to 1936, the society had published five volumes of the scholarly Journal Lietuvių Tauta (The Lithuanian Nation). Its library had 31,000 volumes. The association's archives were especially valuable. By 1940, the archives had a collection of 50,000 folk songs, folk tales, and other examples of Lithuanian oral folklore. The museum had the following departments: ethnography, archeology, history, and natural sciences. In 1907, during the founding meeting of the Lithuanian Scientific Society, Basanavičius expressed a hope that some day the society would evolve into the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences.10 His hopes were in part fulfilled when in 1940 the holdings of the society were incorporated into the newly formed Lithuanian Academy of Sciences.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Basanavičius' death, one of the major participants in the re-establishment of Lithuania's statehood. Having signed the Declaration of the re-establishment of Lithuania's independence on February 16, nine years later, he died on the same date. He was buried in the Rasos cemetery in Vilnius, On a plain gravestone was written: A.A. DAKTARAS JONAS BASANAVIČIUS, AUŠROS ĮKŪRĖJAS, MOKSLININKAS, TAUTOS ATGAIVINTOJAS, 1851.X1.231927.11.16. (Founder of Aušra, Scientist, A Nation's Reviver). Below was written a sentence taken from one of his articles which appeared in Lietuviškoji Ceilunga in 1882: Kada jau in dulkes pawirsim, jei lietuwiszka kalba bus twirta pastojus, jei per mūsų darbus Lietuwos dwase atsikwoszes tasik mums ir kapuose bus lengweu smageu ilsėtis. (When we have turned into dust, if the Lithuanian language will be standing strong, if through our toils the Lithuanian spirit is restored, then even in these graves we will rest easier, happier.)

1 D-ro Jono Basanavičiaus autobiografija. Vilnius, 1938, pp. 12-13.

2 Ibid., pp. 20-21.

3 Basanavičius,J., Iš istorijos mūsų atsigaivinimo. Varpas No. 3, 1903, pp. 66-67.

4 Katkus, M., Raštai. Vilnius, 1965, p. 460.

5 Aušra, No. 1, 1883, pp. 3-7. 6. Aušra, No 3, 1884, p. 52.

7 Aušra, No. 4, 1883, p. 90.

8 Hroch, M., Die Vorkaempfer der nationalen Bewegung bei den kleinen Voelkern Europas. Prague, 1968, pp. 66-71.

9 D-ro JONO Basanavičiaus autobiografija. Vilnius, 1936, p. 87.

10 Lietuvių Tauta. vol. 1. Vilnius, 1910, p. 160.