Editor of this issue: Kęstutis Girnius

Copyright © 1978 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 24, No.1 - Spring 1978

Editor of this issue: Kęstutis Girnius ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1978 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

SWISS RECOGNITION OF LITHUANIA, AUGUST 1921

ALFRED ERICH SENN

University of Wisconsin, Madison

For new states, recognition by the established governments is a matter of life and death. Provisional, or de facto, recognition acknowledges the existence of new states or governments but offers them only limited benefits. Full, or de jure, recognition brings with it extraterritoriality for diplomatic representatives, immunity from legal harassment, and more favorable conditions for trade. Recognition by some governments can of course be more important than recognition by others.

For Lithuania after World War I each recognition represented a step toward full acceptance in international affairs, and the de jure recognition by Switzerland in August 1921 had a special meaning. Switzerland's neutral position in Europe, its role as a center for international organizations, and its long standing hospitality toward Lithuanian students and political émigrés all gave its act of recognition both a geopolitical and an emotional significance. The Lithuanians had worked hard for that particular recognition, but in the end for the Swiss it seemed almost a matter of routine.

The first Lithuanian initiatives seeking recognition from the Swiss government came in February 1918. Juozas Gabrys's Lietuvos Tautos Taryba directed a letter to the Swiss President, Felix Calender, transmitting a declaration issued by the Taryba in Vilnius on December 25,1917.1 On the 12th of February, Gabrys sought an audience with Calender, but he was refused. Instead, on the 15th, together with two colleagues he visited the Foreign Office of the Political Department in Bern. (The Swiss government was rather miffed when Gabrys subsequently issued a press release indicating that he had seen Calender.) The Lithuanians gave the Swiss officials their calling cards and, as one Swiss official put it, "explained the aims of the national movement in the country." The Swiss government was not moved to action; in fact, the Foreign Office instructed its ambassador in Petro-grad to give no indications of support to Lithuanian or Latvian spokesmen.

On May 8,1918, Gabrys's council sent another letter to the, Swiss Federal Government, citing the Taryba's declaration of independence of December 11,1917, but without any mention of the call for close ties with Germany contained in that document. On July 15 Vincas Bartuška wrote a letter calling attention to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk whereby Russia had given up its claim to Lithuania and noting that the German government had recognized Lithuanian independence. The Swiss still took no action, although they duly watched the furor surrounding the election of Wilhelm of Urach as King of Lithuania.

As World War I dragged to its close in the fall of 1918, the Lithuanians stepped up their efforts. On September 12, Augustinas Voldemaras, in the company of the Taryba's representative in Switzerland, Daumantas, visited the Swiss Foreign Office to say that Antanas Smetona would like to visit Calender. Nothing came of that request, but on October 27 Daumantas returned to request recognition of Lithuania. The Swiss replied that they would study the question.

|

|

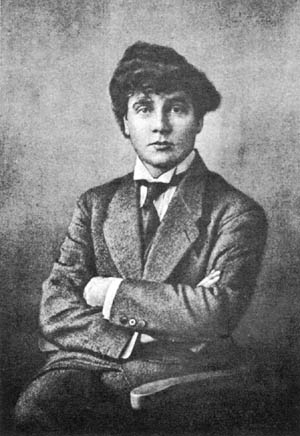

Dr. J. Šaulys, Envoy to Switzerland. |

On November 25, 1918, the Swiss ambassador in Berlin telegraphed his government to report that Jurgis Šaulys wanted to come to Bern to discuss recognition of the new government in Vilnius and to establish diplomatic relations with the Confederation. The Foreign Office responded negatively the very next day: "The trip of Herr Dr. Šaulys seems to have no purpose for the time being, since the question of Lithuania is for now far from urgent." Šaulys thereupon changed his request, and he asked for a visa to come to discuss with Entente diplomats the problem of resisting Bolshevism. At the beginning of December the Swiss granted him a visa for the purpose of consulting Entente diplomats.

The Lithuanians now had established their entry wedge. Daumantas returned to the Foreign Office, and on December 12 the Swiss, while refusing to discuss recognition, agreed to receive him as a Lithuanian representative. On December 14 the Bundesrat, the Swiss Federal Executive Council, formally approved the Foreign Office's decision: "M.Šaulys will be told that the Government of the Confederation will not for the moment consider the question of recognition but that the Political Department will receive visits and communications from M. Daumantas."

On the 16th Šaulys was told of the Bundesrat's decision, and the Foreign Office agreed to permit Jadwiga Chodakaus-kaitė to remain in the country to work with Daumantas., šaulys was himself permitted to remain in Switzerland until the end of December.2

However guarded, the Swiss action amounted to de facto recognition of the Lithuanian government, and months later the Swiss admitted this. The Lithuanians themselves did not completely realize the significance of the Bundesrat's decision. On December 3, 1919, šaulys, again in Bern, visited the Foreign Office and asked the Swiss government to grant de facto recognition, and on December 12 Vaclovas Sidzikauskas came in with the same request. The Swiss responded that they had already taken this step with the Bundesrat's decision of December 14, 1918, and the Foreign Office repeated this statement several times in response to later inquiries from its representatives abroad.

Although the Swiss were therefore among the first to grant Lithuania de facto recognition, they were reluctant to act too quickly on de jure recognition. On April 23, 1920, Sidzikauskas, now the Lithuanian charge in Bern, called attention to the upcoming elections for a Constituent Assembly in Lithuaniahe predicted a victory for the Christian Democratsand pointed out that Lithuania was entering into peace talks with Soviet Russia. Lithuania, he explained, planned to follow the model of the Estonian treaty with the Russians. He hoped that the Swiss would soon grant full recognition to the government in Kaunas. This request brought no response.

On January 13, 1921, the Bundesrat considered the recognition of all three new Baltic governmentsLatvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. The Latvian case, it decided, was the strongest, while the Estonians seemed under strong Bolshevik influence. Lithuanian recognition would have to wait: "Lithuania has not yet been able to establish its territorial boundaries and to secure them; great regions claimed by it are still occupied by foreign troops."

On February 14, 1921, Sidzikauskas tried again, this time listing all the states that had already recognized Lithuania. This time the Swiss Foreign Office was ready to consider the matter, and it requested its representatives abroad to report on the status of Lithuania's recognition. The ambassador in Paris reported on February 24 that France had refused to recognize Lithuania and had posed as a condition "the conclusion of an agreement between the Lithuanians and their neighbors, especially the Poles." The envoy in Rome reported on the 25th that Italy was favorable toward recognition but wanted to act in agreement with its allies; the Italians were therefore awaiting the solution of the Vilna Question. From Brussels came word on February 25 that the Belgian government was awaiting the outcome of the efforts to hold a plebiscite in Vilnius.3 According to a report from Madrid dated February 26, the Lithuanians had not yet approached the Spanish government.

On April 14 the Foreign Office recommended to the Bundesrat that it grant de jure recognition to Latvia and Estonia. As for Lithuania, it noted that de facto recognition had been granted in December 1918, but it considered that the time had not yet come for de jure recognition. The Vilna Question was still being debated, and Lithuania's boundaries remained unsure. Swiss interests in Lithuania were not great enough to demand a decision at this time.

On April 22 the Bundesrat granted de jure recognition to Latvia and Estonia. It deferred action on Lithuania, citing the uncertainties of the Vilna Question. The Foreign Office notified Sidzikauskas of this decision on the 28ththe news was delayed because Sidzikauskas had been travellingand declared, "We count on the opportunity to recognize Lithuania soon, all the more since we have now come to a good resolution with Latvia and Estonia."

On the 29th Sidzikauskas came to the Foreign Office to obtain details, and the Swiss declared that they were awaiting the resolution of the Vilna Question, the outcome of the Brussels talks, and the action of the Great Powers. Sidzikauskas vainly attempted to show what good relations Lithuania enjoyed with the Entente powers: the French were on the verge of recognizing Lithuania; the English were extremely interested in the country; and, on the other hand, the Lithuanians had sent home the Soviet representative because he had run up too many unpaid bills.

Rather more significant for the Lithuanians was the decision of the Swiss Justice Department in this same month of April no longer to require caution or bond from Lithuanians resident in the country. The Swiss accepted the readiness of the Lithuanian mission to cover the costs of illness and emergency travel for the estimated 100 Lithuanian families and 50 students in the country. A Foreign Office memorandum on June 1 noted that the Lithuanians now enjoyed "a situation more favorable" than that of the Latvians and Estonians whose countries had been recognized de jure. The Foreign Office decided again to poll its representatives abroad.

|

|

Juozas Puryckis, |

Although the situation among the Great Powers had not changed, the Foreign Office proceeded with its own investigation of the conditions in Lithuania. On August 9 it recommended that the Bundesrat recognize the government in Kaunas. Although the Vilna Question had not yet been resolved, the office's long memorandum noted the recognitions which the Lithuanians had already received and declared that all of Lithuania's boundaries except that with Poland had been set. A Constituent Assembly was in session and was planning a radical land reform. The Lithuanian Foreign Minister, Juozas Puryckis, received special note for the fact that he had studied at the University of Fribourg. "The government," the Foreign Office stated, "seems solidly established and supported by the majority of the country."

Turning to the question of Swiss-Lithuanian relations, the memorandum commented that the Lithuanians put great stock in recognition by the Swiss. "Up to now,' it pointed out, "Switzerland has had no representative in Lithuania, as a result of which the colony and Swiss interests are deprived of any protection." The document concluded by recommending recognition with the one reservation concerning the question of the country's boundaries.

On August 16, 1921, the Bundesrat accepted the Foreign Office's recommendation. The Foreign Office drafted a letter announcing Lithuania's de jure recognition on the 18th, and on the 19th mailed it to Sidzikauskas, who had left for Kaunas on the 10th. The head of the Political Department, Guisseppe Motta, sent Sidzikauskas a telegram: "I am happy to report to you that the Swiss Federal Council recognizes the free and independent state of Lithuania de jure. A letter follows."

The news was received with jubilation in Kaunas. The Lithuanians hoped that now the Entente powers would not pressure them so for an agreement with the Poles over the Vilna Question. The Lithuanians also foresaw many diplomatic doors now opening for them. Then too, many Lithuanian leaders had a special feeling for Switzerland. On July 30, in addressing a Swiss group in Kaunas, Puryckis had spoken glowingly of how Switzerland had offered "asylum for political exiles," had served as the "cradle of various Lithuanian organizations," and had been the site of "the first Lithuanian conferences in Lausanne and Bern."4

In its formal response on August 25, signed by Puryckis and Kazys Grinius, the Lithuanian government welcomed the news of recognition and added the comment, "During the World War, numerous political as well as charitable institutions have found refuge in free Helvetia, profiting from the great hospitality of the Swiss." The reference to political institutions raised some eyebrows in Bern: had the Lithuanians violated principles of neutrality during the war? The Swiss government also received a complaint from its consul in Riga that he had not been notified of the recognition; he had therefore been taken by surprise when Dovas Zaunius visited him on August 24 and gave him the news. Nevertheless, on September 8, the Bundesrat simply took formal note of the exchange of letters with the Lithuanian government, and the two governments proceeded to establish normal relations.

Various Lithuanian newspapers speculated that Swiss recognition portended a new show of sympathy for Lithuania among the Great Powers or at least in the League of Nations, but that was not to be. Switzerland had recognized Lithuania in order to regularize its relationship with all three new Baltic republics; it had not acted with any special knowledge or intention.

1 Unless otherwise noted, all documents referred to in the text are to be found in the archive of the Federal Political Department, Bern,

Bundesarchiv, EPD, 2001 (B), Akz. 2. The Swiss Foreign Office is a part of the Political Department.

2 On Šaulys's work, see Alfred Erich Senn, The Emergence of Modern Lithuania (New York, 1959), pp. 85-86.

3 On the efforts of the western powers to force an agreement between the Poles and the Lithuanians in 1921, see Alfred Erich

Senn, The Great Powers, Lithuania, and the Vilna Question (Leiden, 1966), pp. 47-82.

4 Notation in my father's diary which he kept vhile living in Lithuania in 1921.