Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas

Copyright ę 1981 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 27, No.4 - Winter 1981

Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright ę 1981 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

PRANAS DOMđAITIS: REDISCOVERED SCION OF EXPRESSIONISM

To those of us on the periphery of the international art world, PRANAS DOMđAITIS scarcely rings a bell. To those "in the know" his is a name that is commanding increasing respect from serious art collectors. And well it might: after years of basking in the limelight of German Expressionism, Domaitis retreated ever deeper into the wilderness, only to re-emerge Ś after his death Ś as an artist who most profoundly expressed one of the most "timelessly modern" themes: man's exile from society and civilization, his return to the Earth and Inner Self in search of Transcendence.

"Basking in the limelight" is perhaps too strong a word: Domaitis was a retreating figure who from beginning to end shunned all forms of outward success. Nevertheless he made enough of a name for himself in the 1920's and 30's to draw the ire of Hitler and to have his work banned from Germany. Even though Domaitis personally never sought to capitalize on that fact, his name is even now beginning to resound again in the international art community as testimony to the ability of true art to survive all of the destructive forces that modern totalitarianism and barbarism marshals against it.

Domaitis began and ended his life's journey in what civilization considers its "backwaters": he was born on August 15,1880 in a small Lithuanian hamlet on the border with Germany near the Baltic Sea; he died on November 14, 1965 in Cape Town at the edge of the vast and desolate South African Karoo. Between these two polar points, over a span of 85 years, his life moved peripatetically in a pattern of war, exile, struggle, and discovery all too characteristic of 20th century personal histories.

For the first 27 years of that life Domaitis was a farmer, a tiller of the soil who painted in his spare time. He did not begin his formal education until 1907 when, at the recommendation of Max Liebermann, he received a stipend to study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Koenigsberg. After graduating in 1910, he went to Berlin to work under Lovis Corinth, then travelled to Paris, London, Amsterdam, and Florence for further studies. Shortly before the outbreak of World War I, he visited Edvard Munch in Norway, a meeting that proved decisive for the development of his style. He spent the war years on his parents' farm and in military service, then sought peace in the rural quiet of Austria and Bavaria before resuming his travels across the European continent. After his first one-man show at Callerie Moeller in Berlin, he exhibited in other German cities (Breslau, Essen, Hamburg, Koenigsberg) as well as in Switzerland, Austria, Romania, and Turkey. But in 1938, after having been included, along with Munch, van Gogh, Nolde, Kirchner, Mueller, Dix, and many others, in the notorious exhibition Entartete 'Kunst' (Degenerate 'Art', organized by Hitler for the specific purpose of ridiculing Expressionist and other "decadent" art styles), Domaitis' work was removed from all German museums in 1938. During the war he painted "harmless" still-lifes before moving to southern Austria in 1944 and exhibiting in Voralberg, Innsbruck, and Bregenz. In 1949 he emigrated to 5outh Africa, where his wife, opera and concert singer Adelheid Armhold, was offered a lectureship at the University of Cape Town. Entering a period of intense creativity, Domaitis became one of the dominant figures in South African art, with exhibitions there and in Rhodesia, the United States, Canada, and Brazil. After his death, commemorative exhibits of his work were held in Cape Town; Bielefeld, Germany; and Honolulu, Hawaii.

Although the artist never formally allied himself with any specific school, he moved from the romantic realism and what the well-known art critic Karl Scheffler called the "spiritual impressionism" of his youth towards an ever more personal Expressionism, fusing "something of Chagall's enchanting visions, the guileless piety of Rouault, the resonant colour of the expressionists, and the intuitive wisdom of the peasant" (Graham Watson).

In her extensive monograph on Domaitis, Elsa Verloren van Themaat writes that "sombre as they are, Domaitis' paintings are yet warm and peaceful: a combination that evokes a transcendental or religious rather than a realistic world. He created this atmosphere by using stark contrasts and basically heavy, strong colours, outlined in black, as well as cold colours against which a small wealth of warm colours would glow and sparkle." (. . .)

"Like the German Expressionists of the time, Domaitis was concerned with a reality behind the apparent world and was able to convey clearly in paint his own personal feelings towards an external subject and thus give it a personal spirituality. B.S. Myers describes these artists as 'overcome by visions not concerned with catching the momentary effect of a situation but its eternal significance'.

"The external images with which Domaitis expressed himself are widely recognisable and introduce the spirituality of his art. That he concentrated on the spiritual was not a coincidence but relates to his background in north-eastern Europe, to the beginning of a career in the influential sphere of the German Expressionists at the start of the century, and to its history which had a direct effect on his personal life. It was typical of that part of Europe, the paintings of whose artists, such as Chagall, Soutine, ╚iurlionis, possess an otherworldly quality. Coming from this area, Domaitis was not so much an innovator as a 'painter-spokesman' for a tradition and a belief which stretched back for centuries."

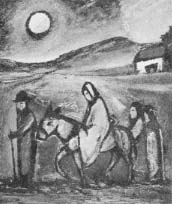

The Lithuanian folk art tradition and its natural religious mysticism have indeed profoundly influenced the design and atmosphere of Domaitis' work. (Not the least example of this influence is the commanding presence of a strange midday moon in ever so many of his paintings.) Thematically, he preferred scenes of village life, human figures, a few religious subjects to which he obsessively returned again and again (cf. the Annunciations, the Crucifixions, and the Flights into Egypt, the latter embodying his personal response to the 20th century experience of exile and uprootedness), and, above all, landscapes Ś especially those of the South African Karoo, where he rediscovered the Baltic lowlands of his youth and between whose earth and sky he at long last, after years of wandering, found peace.

Domaitis never severed his biographical relations with his Lithuanian homeland. Although he never lived there for more than a year, he visited Lithuania several times and even took out Lithuanian citizenship in 1920, after the independent Republic of Lithuania had been formed. In 1938, he ceased using the German form of his name (Franz Domscheit) in place of 'Pranas Domaitis'. After the war, in Austria, he struck up acquaintance with Lithuanian exile artists and started to relearn the Lithuanian language that he had forgotten since leaving his parents' farm many years ago.

Nevertheless the Lithuanian artistic and intellectual community did not pay Domaitis the respect he deserves until recently when, at the insistence of Adolfas Valeka, the Lithuanian Foundation of Chicago acquired a sizeable collection of his works. This collection forms the basis of an organized effort to introduce Domaitis to art museums and galleries throughout North America and Europe. To this end the Foundation's Visual Arts Committee is gathering the necessary documentation on the artist's work. The effort to extend Domaitis' renown beyond the perimeters of South Africa is abetted by competitive pressure from independent art collectors seriously interested in this unduly neglected scion of the Expressionist movement. There is little doubt that with increased exposure in the art capitals of the Western world, the work of Domaitis will reconquer its place in the history of contemporary art Ś alongside that of Barlach, Munch, Nolde, and Schmitt-Rotluff Ś as a powerfully unique variation on the Expressionist theme.

MYKOLAS DRUNGA

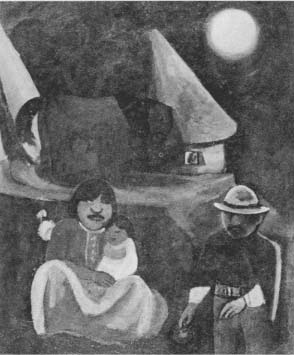

Gypsies from Rumania (Oil, 1928)

Triptych (Oil, 1955)

Three figures, (Oil, 1955-65)

Flight into Egypt (Oil, 1918).