Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas

Copyright © 1984 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 30, No.1 - Spring 1984

Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1984 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

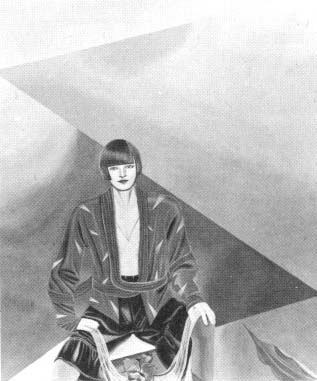

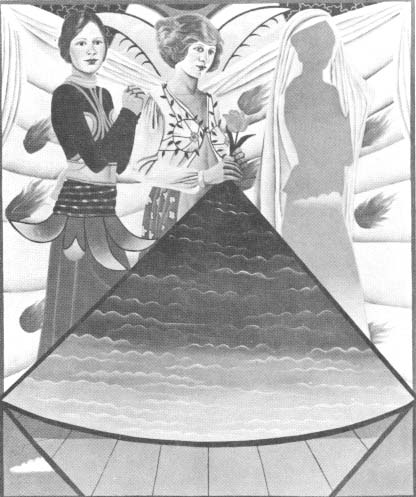

CONCERNING THE ART OF AUDREY SKUODAS

An Interview

Although the art of Audrey Skuodas has at times been called "Surrealist" (her paintings were included in an exhibition entitled "Surrealism Now") and "Art Deco," and although it does in fact contain elements of both, it defies any attempt at classification. Her work is uniquely and unabashedly Audrey Skuodas, and it would be too facile, even irresponsible to tag it as some "-ism" or another. It has been described as "sumptuous, color-keyed emotional experiences," "figurative fantasies". as being "inspired by Art Deco" but nevertheless "very much her own" displaying an "unmistakable style," and even as "tongue-in-cheek satire on romance, patriotism, maternity and what not." Again and again one reads that her paintings are haunting, provocative, puzzling and intriguing.

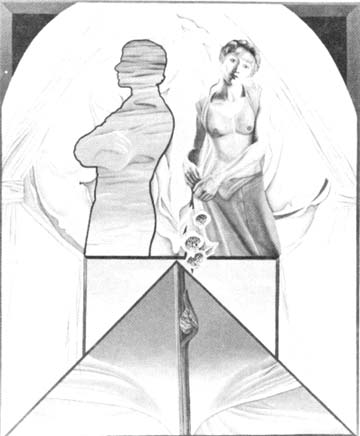

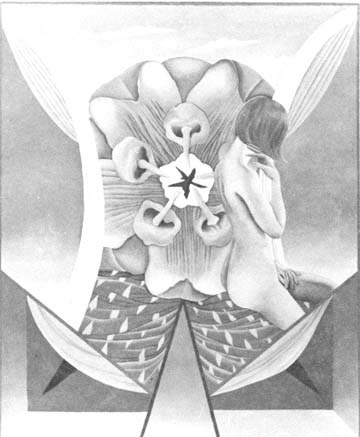

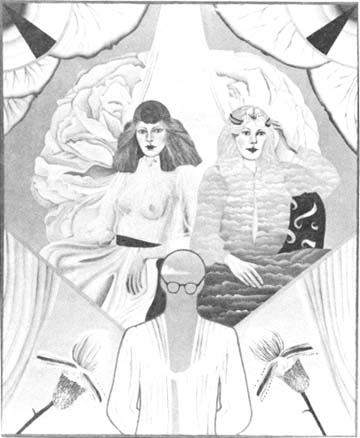

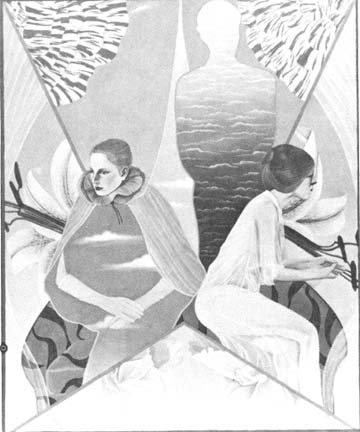

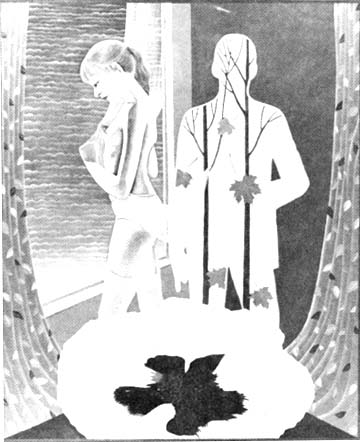

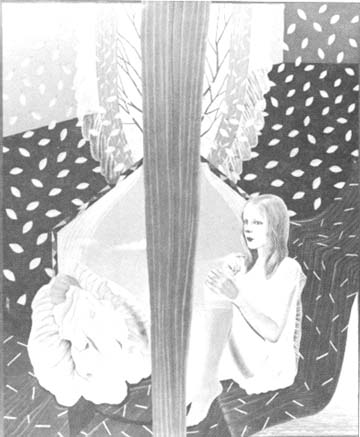

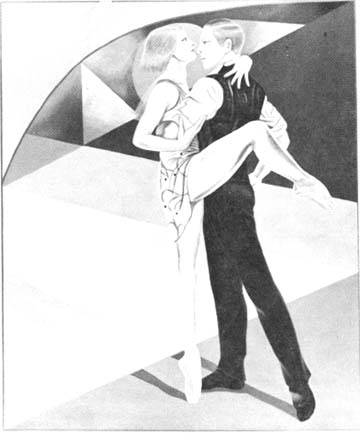

Indeed, Audrey Skuodas' pictures are in a sense mystifications, possibly latent allegories, though not necessarily deliberate or conscious. They seem to be telling something, a story of love perhaps, of human relationships, but its meaning inevitably eludes the viewer. Figures, primarily female, stand or sit mysteriously silent and still, as though caught in the middle of a motion — a dreamlike motion. They appear to be waiting, dreaming, contemplative, introspective. And almost always these women and girls bear a striking resemblance to the artist, so much so, that one could term them as modified or stylized self-portraits (even the occasional male figures display an uncanny likeness to Audrey Skuodas.) These women who are sometimes nude or half-clad or draped in exquisite garb are placid, their features still and composed, very aesthetic but highly stylized, almost doll-like. Yet curiously, although they seem chaste and pristine, they at the same time radiate a definite sensuality but in a vague, withdrawn sort of way, almost like dream-women, not really possessed of sex. The motionless, often unnatural stances of the figures seem so deliberately affected by the artist that they appear almost symbolic, as do the giant voluptuous flowers, the stylized and fanciful drapings, the windows, seascapes and the enigmatic, Magritte-like transparent silhouettes. Quite clearly the artist is indulging certain fancies and fantasies; the paintings seem to represent an aesthete's dream world, and the responsive viewer asks oneself: what are these women dreaming about, what are they waiting for, longing for? What has just happened and what is about to happen?

Audrey Skuodas' mode of painting is very careful, very delicate — there is no trace of impasto although she maintains that she paints very vigorously, that she almost "attacks" the canvass with the energy of an abstract expressionist. The brushstrokes are invisible and the outlines are clearly defined. The flesh tones are always more pastel-like rather than warm and at times one has the feeling that the artist is occupied with color and composition more than with the subject. In addition to the large 5' x 6' acrylic paintings Audrey Skuodas has also made wood sculptures and so-called soft sculptures, i.e. stitched three-dimensional creative forms. Recently she has begun to utilize different materials such as paper, crayon, lace, metallic fabrics, sequins and glitter. The resulting collage-pictures are very intricately decorative with an even more distinct '30s flavor than is true of her large canvasses.

Audrey (Audrone) Skuodas was born in Kaunas, Lithuania. Like so many of her compatriots who fled from the advancing Soviet armies, at the end of World War II she ended up in a camp for displaced persons in Germany and did not arrive in the United States until 1949 where her family settled in DeKalb, Illinois. After completing her public school education there, she entered Northern Illinois University in 1958 and received her B.A. in 1962 and her M.A. in 1964. One year later she married John Pearson, an artist who already at that time had exhibited his work in England and Germany. After two years in Albuquerque, New Mexico, two in Halifax, Nova Scotia where she taught drawing at the Nova Scotia College of Art, and another two years in Cleveland, Ohio, Audrey Skuodas came to Oberlin, Ohio where her husband John Pearson is a professor of art and chairman of the Art Department.

The work of Audrey Skuodas has been shown in many exhibitions: in the Ciurlionis Gallery in Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the Anna Leanowans Gallery, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax, Nova Scotia; in the "Young Nova Scotia Artists' " Show in the Centennial Art Gallery, Halifax. She also has held nine one-woman museum shows in other cities in Nova Scotia. In 1971 she had a one-woman show at the B. K. Smith Gallery of Lake Erie College and was represented in group exhibitions at the New Gallery of Contemporary Art in Cleveland. Her work was also shown at the Evanston Art Center, Evanston, Illinois and seven times at the very prestigious Cleveland Museum of Art Annual May Show. It should also be mentioned that as early as 1967 Audrey Skuodas created four large murals for the Richard Gray Gallery of Chicago.

When l visited Audrey Skuodas last, she was making preparations for her one-woman show at the DBR Gallery in Cleveland, due to open on October 18. She was loading the huge canvasses onto a likewise huge gray Ford station wagon which bears the bumper sticker "Happiness is being Lithuanian." Knowing that for the readers of Lituanus the artist's "Lithuanian connection" would be of special interest l asked her what significance the sentiments expressed by the bumper sticker had for her:

A.S. Where we lived there virtually were no Lithuanians. The nearest town where any Lithuanians lived was some forty miles away, and there were only nine families there. My parents had kept up a relationship with them, but obviously one couldn't do it on the kind of scale which would have been possible in Chicago. When l was in college l started to make Lithuanian friends and went to some of the events they had. There was a great sense of loss inside of me, l wanted to be part of these occasions because l felt it was part of me but in a sense l was already an outsider, l wasn't fluent in anything. l tried to participate in their various conferences and gatherings, but l always felt very out of place. Obviously there were many factors contributing to this alienation, not knowing the people, not knowing all the information that was bantered around, no longer being quite as fluent in Lithuanian, etc. But l do have a craving to hang on to it. l feel it's part of me. l don't want to lose it, and part of that l think is why l feel alien to the American sensibility. It's just wanting to find a niche for oneself, something to which one does belong. l feel l am in contrast to much that exists around me. l find l can definitely identify better with a European sensibility.

S.P.R. Would you say that your work is in any way informed by your Lithuanian heritage? Here and there, l think, l do detect folk motifs, and l seem to remember reading that you consciously incorporate them in your work.

A.S. The little Lithuanian art I did see no doubt had an influence on me. l remember my parents had several books containing wood cuts by artists from the '30s, very dynamic, dramatic kind of constructions and those l think influenced me. As for my work, l think there is a sort of brash directness, or at least used to be there, l don't think it's there so much now. l think it's being refined somehow. As l get older l notice the paintings become much quieter, gentler. But my early work could be immediately identified with the folk aesthetic. And this isn't something l willed. l think it's in my make-up. It's probably influences I'm not even aware of. Whatever l have developed as a human being up to that point, it comes out. For example, l have often put very ethnic type garb on the female figures or the children, and if not, l have decked them out in flowers and garlands which is really a very folk type of thing to do. So l do utilize elements of that sort, but l think that the whole thrust of the work is not toward any theme of that nature, it's just that these little influences come out and show up here and there.

S.P.R. Let's go on a bit with the same topic if you don't mind. l mean your Lithuanian influences. On your bookshelf l noticed a rather worn copy of the Lithuanian children's story Broliř

Ieđkotojai with lovely illustrations in it. Judging by the condition of this book, you must have had it already as a child. Perhaps

I'm really way off, but l find some of the things you do in your paintings very reminiscent of this type of illustration. l couldn't point out any specifics but nevertheless there is something there. Am l on the right track here?

A.S. I'm sure this little Lithuanian book must have had a truly subliminal import on me, its illustrations and their entire layout. It's very '30s, you know, and my predilection for this period is quite evident in my entire work, as any-one can see.

S.P.R. How old were you when you began painting?

A.S. l guess l always have. l remember my mother telling me that when l was three years old in Lithuania l did a picture of Stalin. l drew him and then took things and threw them at him. l was very creative. l built fairy houses and l fully believed — l could swear — l could see those little people going in and out. Perhaps I was especially endowed with imagination. I don't know if all children have this, that they go through the same thing. I remember reading a book on Anna Pavlova and immediately doing drawings of dancers.

S.P.R. Let's go back for a minute to the Lithuanian theme. You are, I'm sure, familiar with the work of Čiurlionis whose name, incidentally, does not appear in any of the encyclopedias nor is it mentioned in the standard art histories. In fact, I would venture to say that he has been all but unnoticed in the art world and still I think he is probably not all that insignificant as an artist. What would you say, and more important, what do you think of him?

A.S. I identify with some of his paintings. "Pavasario sonata" for example, and many others I find very meaningful, very sensitive. It's like he loved it all the way through. It is not set and rigid, it still breathes in spite of all his miniscule involvement. It still has the capacity to be open, at least I feel that when I look at it. And I find that quite amazing because in a sense when an artist gets involved to that degree, it seems to me, it would just have to become sterile and meaningless and yet when I look at his paintings, some of them, I see that he still has retained that energy and freshness. The painting never died; it never was closed off.

S.P.R. Could you say what artists have been of special importance in your development, have influenced you perhaps? Or any specific paintings?

A.S. I don't know if "influenced" is the right term, because the people with whom I absolutely identified I encountered when I was already set in the direction I was going. Take Magritte, for example. When I look at the paintings I did when I was in High School — it's all there, what I am now. It was in college, towards the end of college, very late actually, that I became aware of Magritte and it gave me courage, and I'm sure it influenced me even if it was not in any specific way. Definitely he made me think: "Anything is possible. I mustn't be afraid of whatever I want to be as an artist." As for specific paintings, well, at the Phillips Collection I saw a little painting by Arthur Dove called "Cows in a Pasture" and it made an incredible impression on me. Later I tried to think why did I identify with this painting? I think it was the application of paint I identified with, it is the way Georgia O'Keefe, another artist I love, paints. At that point I wasn't really aware of Georgia O'Keefe but Arthur Dove, I think, is in many ways like Georgia O'Keefe. His sensibility is a lot like hers. Basically I think it was the painting surface and the shapes used that made the greatest impression on me. It's the way the paint is applied, very thinly, very sensitively, strictly serving the purpose of imbuing the painting with an evocative power. As for Georgia O'Keefe, I can think of nothing more beautiful or satisfying than looking at her paintings.

S.P.R. At your current show at the DBR Gallery I was observing the people who came to look at your pictures and listened to their comments and the questions they raised. Perhaps the most frequently asked questions were: "What do you think she's trying to say? What does this symbolize?" My friend with whom I went there also had similar questions and I had the same experience at one of your earlier shows at Oberlin College. Would you say that this sort of response is typical on the part of your viewers?

A.S. I know that people do react to my paintings, and not always positively, very often not positively. They are intimidated. They either can't look at it or are angry about it or they are troubled by it, but they certainly do have to react to it. In a sense that's a guarantee that I have communicated something. That's the nature of art, that's its purpose. To arouse something, to awaken something, to touch a sensibility or a chord that perhaps one hasn't been aware of.

S.P.R. And how would you answer the question as to what your paintings express, what is their hidden meaning which every viewer is convinced is there? Is there symbolism in the cryptic backgrounds, the flowers for example?

A.S. There definitely is symbolism, but I couldn't tell you what it is. I identify with flowers because they are evocative of so much, they are beautiful, they are so delicate. My paintings deal with a kind of sensuality and flowers certainly personify that. But basically I really don't know what I'm dealing with. I feel it deep inside me, but I don't know. That's why I work. It's like each painting is trying to reach toward some sort of evocation or communication or explication. It's like an opening up, and it's probably a lot of things that trouble me. What is it in a relationship that is significant? My paintings certainly deal with that but to what degree and how exactly I don't really know, but I know that that's very essential. I guess I'm speaking for a kind of beauty, maybe I'm trying to project something that can't exist. Maybe it's the old romantic notion of what love and relationships could be.

S.P.R. I dare say that when I look at your paintings I get the distinct feeling that you paint out of a romantic nostalgia, and quite unabashedly so, without any pretensions and I admire you for it because it takes courage to paint like that today, I think. But let me ask you another question. Kokoschka once said that "an artist should refrain from settling down to the repetitive routines of his own particular manner and style which may blind him to the freshness and novelty of a world which never repeats itself." The undiscerning viewer looking at your paintings could say that you are always dealing with the same thing, that your central motif has always been the female figure and so on. How would you respond to this challenge and in what way, do you feel, has your work evolved?

A.S. As I've mentioned earlier, my painting is in a sense searching, and searching denies the notion of repetition. I'm sure that my whole process is really a reaffirmation of Kokoschka's statement. My concerns are still basically the same, but as I learn and mature and my awareness expands I have to approach my painting differently. This is what causes change. There are obviously all kinds of influences which enter. My paintings are my life. When Cadence and Jason were born, I painted a Madonna and Child in the background of my pictures. It symbolized something for me and it was a symbol I needed at that point in my life. My work has changed and developed considerably over the past ten years.

S.P.R. Audrey Skuodas, I thank you for this interview.

Stella Pagalys Rosenfeld

1983

1976

1979

1979

1980

1980

1987

1987

1982

1983

Acrylic on canvas, 5'6" x 6', 1983.