Editor of this issue: Thomas Remeikis

Copyright © 1984 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 30, No.2 - Summer 1984

Editor of this issue: Thomas Remeikis ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1984 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

THE POLISH-LITHUANIAN CRISIS OF 1938

Events Surrounding the Ultimatum

ROBERT A. VITAS*

Loyola University of Chicago

THE VILNIUS DISPUTE**

At the conclusion of World War I, new states began carving themselves niches on the European continent. Two such countries were Poland and Lithuania. They had been dismembered in the partitions of the late eighteenth century. Immediately upon reconstitution, both states conflicted over Vilnius and its surrounding territories. The city was the historic capital of Lithuania. However, after the Union of Lublin in 1569, Vilnius became a more cosmopolitan city. Gradually, Poles came to outnumber Lithuanians. Lithuanians continued to predominate in the countryside.

Lithuania declared her independence on February 16,1918. This was followed by two years of turbulence. The vanquished Germans retreated and the Bolsheviks entered the Vilnius territory in late 1918. In turn, Polish and Lithuanian volunteers drove the Red Army out of Lithuania Poland entering Vilnius first on April 19, 1919. During the summer of 1920, the bolsheviks re-occupied the territory. Subsequently, Russia concluded an armistice with Lithuania, turning over to her the capital and surrounding areas. The peace treaty caused renewed fighting to break out between Poland and Lithuania. Finally, after much maneuvering including the intervention of the League of Nations the Treaty of Suvalkai was signed on October 7,1920; the Vilnius territory was to remain in Lithuanian hands.

This situation was to change with lightning speed. Just two days after the signing of the treaty, Polish general Lucjan Zeligowski, with Marshal Jozef Pilsudski's blessing, staged a rebellion and led Polish forces into the eastern third of Lithuania, occupying Vilnius. The Lithuanian counterattack was halted by the League of Nations; diplomatic efforts failed to bring Vilnius back to Lithuania. The Conference of Ambassadors recognized the existing border in 1923.

The inter-war years were to see continuing tensions between the two countries over the Vilnius question. Lithuania would not officially renounce the capital; Poland would not give up the predominantly Polish city. A stalemate ensued for eighteen years, despite secret and sometimes high-level contacts between the belligerents. Nothing appeared able to break the deadlock, which included the lack of diplomatic relations and a technical state of war. An administration line was created between the antagonists. It was here that Polish-Lithuanian hostility was focused.

THE BORDER

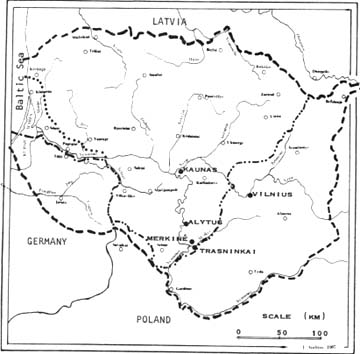

The administration line which divided Poland and Lithuania ran 520 kilometers through the eastern third of Lithuania. It began in the north near Dvinsk, and ran through Giedraičiai and Merkinė to the Nemunas River halfway between Seinai and Gardinas, ending in the south at Vištytis. A "no-man's land" approximately one kilometer wide divided Polish and Lithuanian forces. There were no formal markings on the Lithuanian side; however, high poles with straw brooms at the top designated the Polish side of the frontier. Lithuanian border police patrolled one side, while the Poles used a component of their regular armed forces, the Polish Frontier Guard Corps (Korpus Ochrony Rogranicza KOP), to supervise the line.

MAP OF LITHUANIA

KAUNAS, VILNIUS, ALYTUS, MERKINĖ, TRASNINKAI HIGHLIGHTED

Borders demanded by Lithuania after the conclusion of World War I. The southwestern border was never to be realized

Border with Prussian Germany.

Administration line between Poland and Lithuania.

Border between Klaipėda Territory and Samogitian region of Lithuania (Žemaitija).

Skirmishes were not uncommon along the frontier. Although the area was usually quiet, there were also instances of poachers, border runners, and outlaws darting back and forth across the line, occasionally drawing fire from Polish and Lithuanian guards. There were also non-violent events which nonetheless produced tensions. Border posts were sometimes moved in the night. A superficially humorous example was also reported. Apparently, a Lithuanian farmer constructed a haystack on his land. During the night, however, the stack was quietly moved to the Polish side of the line. While it was a relatively minor incident, accumulated minor events served only to heighten tensions. This caused the exchange of gunfire to become more frequent, especially as 1937 wore on.1

The border zone was decidedly an unhealthy place to look over even momentarily. Guards were ever on the alert and ready to take pot shots at suspicious shadows. Poachers and smugglers found it very precarious to carry on their nefarious activity.2

Since 1927, at least seven guards had been killed and thirteen wounded in various incidents.3 Yet, there was a measure of cooperation on the frontier. For example, Lithuanian farmers could be allowed by Polish officials to cross the line and perform farm-work on land that may have ended up in no-man's land or in Polish hands.4 However, apart from minimal official traffic that had been agreed to by the respective governments, there were few breaches of the line.

On the Lithuanian side, responsibility for guarding the border was divided up into regions by the authorities. For example, the Alytus area border police district was divided into six regions. The district was administered by a chief located in Merkinė. Each of the six regions was based in small towns or villages. For our purposes, we will focus in on region two. Here the line zigzagged between the Nemunas and Merkys rivers. The police outpost of this region was located in the village of Trasninkai. It was this village which on March 11. 1938 nearly became the Sarajevo of World War II.

THE TRASNINKAI INCIDENT

The Trasninkai incident is surrounded by mystery. Depending on which source is consulted, the details vary from a group of Polish soldiers to a single soldier; from an accidental Polish presence on Lithuanian soil to an act of provocation by one or the other side. Some Lithuanian historians even mistakenly place the date of the incident as being March 7.5 Others disagree as to whether the Polish soldier died that morning or in the evening. The most detailed account that this writer could piece together is as follows.

In the early morning hours of Friday March 11 near the village of Trasninkai, Lithuanian border police officer Justas Lukoševičius was on a routine patrol when he heard two, then three shots. He informed his superior officer, Vaitkus, who in turn instructed Lukoševičius to investigate the matter. Upon returning to the scene, he spotted a Polish soldier running in the bushes, apparently in the direction of Polish territory. Lukoševičius called for him to halt. Instead, the Pole fired one round in his direction from the bushes. Lukoševičius returned the fire with four rounds. Six rounds were subsequently fired at Lithuanian police officers who had gathered at the scene.

A search uncovered Stanislaw Serafin, a recent recruit to the KOP, who was lying in the bushes mortally wounded. He was brought to Trasninkai where he died later that morning.

The chief of the Alytus border police district, Januškevičius, contacted the commanding officer of the KOP 23rd battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Zabinski. Januškevičius invited him to participate in an autopsy. Instead, Zabinski told the Lithuanian chief to return the body, which was done the next day, Saturday, on the Varėna Bridge. At that time, it was agreed that Januškevičius and Zabinski would meet there the following day, i.e. Sunday March 13 at 2 P.M., to discuss the matter. However, when Lithuanian officials gathered on the bridge at the appointed time, Zabinski did not arrive. A Polish sergeant appeared in his stead and informed the Lithuanians that the colonel had nothing to discuss, since "the issue was to be decided by the Polish Republic."6

Usually these matters were settled through meetings between local authorities, and on this occasion, at 5 PM in the afternoon of March 11, the Polish commandant in the region announced that the unfortunate soldier had mistakenly crossed the frontier . . . Ordinarily, Polish frontier officials would send their reports on such incidents to Warsaw where government officials would consider their political significance. Then the government, perhaps two or three days later, would issue a communique summarizing the event. This time the Warsaw press broke the news almost immediately, and the border incident quickly developed into an international crisis threatening at the very least the partition of Lithuania if not a general East European conflagration.7

The Lithuanian government expressed sorrow over the incident and extended condolences to Serafin's family. It was hoped that normal procedures would be followed. On the face of it, Trasninkai did not appear to be much different from previous incidents. Why, then, did a seemingly insignificant matter embroil Polish and Lithuanian officials and alarm European diplomats? The answer must be sought in the socio-political milieu of Europe in the tense months before the outbreak of the Second World War.

TRASNINKAI IN PERSPECTIVE

Practically simultaneous with the Trasninkai incident was the Anschluss of Austria. The Czechoslovakian situation was also unstable. As a result, with the aid of allied appeasement, the fragile interwar peace of Europe was being threatened by Adolph Hitler. Poland was watching events with a keen eye. Germany was becoming more and more of a threat to Polish national security. It was becoming increasingly evident to Polish political and military leaders that their country would not be able to defend itself single-handedly. Therefore, they looked for options to strengthen Poland's hand vis-a-vis the Reich.

One option was the Lithuanian card. The lack of diplomatic relations had been a nagging and embarrassing problem for almost two decades. It was unusual, to say the least, for two neighboring countries to lack official ties, despite the hostility that emanated from the Vilnius dispute. The restoration of relations and the careful cultivation of Polish-Lithuanian amity could serve as an effective counterweight to Hitler, possibly turning his eyes from the East. The Trasninkai incident gave the Polish government an opportunity to rid itself of the Lithuanian thorn in its side; namely, it provided the circumstances for the renewal of diplomatic relations, regardless of how brutal the procedure may have been. Yet, the government also had to contend with the demands of the Polish citizenry. Poles were demanding restitution for Serafin's death.

REACTION TO TRASNINKAI

Border incidents were usually met with little fanfare. However, in the Trasninkai case, the Polish press claimed that the incident had been the result of Lithuanian provocation.8 The announcer of Warsaw radio spoke in excited tones. Demonstrations broke out in five Polish cities, including the capital. There are indications that both the army and the Camp of National Unity (Oboz Zjednoczenia Narodowego OZN), led respectively by the Inspector General of the Polish Armed Forces Marshal Edward Smigly-Rydz and General Stanislaw Skwarczynski, had a hand in the initial inflammatory news reports and demonstrations.9 Apparently their staged character was rather obvious since Soviet Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov felt that the demonstrations were "undoubtedly artificial and stimulated."10 The Poles chanted "Do Kovno, do Kovno!" "On to Kaunas!" In addition, the crowds called for the punishment and occupation of all Lithuania. Anti-Jewish riots also broke out as a response to their alleged unpatriotic attitude.

Demonstrations were not limited to native Polish soil, but also occurred in Vilnius. There, too, the demonstrators called for the seizure of Lithuania. They also took action of a more punitive nature; the windows of whatever were left of Lithuanian institutions and establishments in Vilnius were smashed.11

Events unfolded while Polish Foreign Minister Colonel Jozef Beck was out of the country. He had paid a state visit to Rome. Now Beck was in Sorrento, Italy, where he was planning to rest for ten days. The news of Anschluss and Trasninkai reached him one after the other on Sunday March 13.12 He had earlier concluded that Poland would have to take an active stance with regard to the movements of the Reich:

"I ... considered that complete passivity in view of the German expansion would in any case be dangerous. If we had to maintain our position in Eastern Europe we should think of finding an assurance for Polish interests, should anyone think of violating them. It was clear that we could not think of any sort of race, running for who-would-get-the-most-problems-solved, but simply stressing the fact of our vigour and, without getting entangled in any dangerous conflict, of giving a warning that none could violate our interests unpunished."13

In his memoirs, Beck relates this thinking with the Lithuanian border incident: "[The Trasninkai] incident symbolically coincided with the conclusion I had made. I was indeed most inclined to use the existing tension for a quick settlement of normal relations with Lithuania."14 Therefore, an indirect result of Anschluss was the ultimatum to Lithuania, which subsequently led to the establishment of diplomatic relations between Kaunas and Warsaw.15

Beck immediately decided to cut short his stay in Sorrento and return to the capital. He telephoned the president and requested that a routine meeting be conferred at the Royal Castle, the presidential residence, consisting of President Ignacy Moscicki, Beck, the Prime Minister Marshal Smigly-Rydz, and the usual retinue of deputies and aides. Beck was on a destroyer en route to Naples, from whence he would fly to Warsaw. Aboard ship, he drafted his position and proposals for the meeting.16

Meanwhile, the domestic situation in Poland was becoming more intense. Government officials, minus Beck, were already taking it upon themselves to draft demands addressed to the Lithuanian republic. They called for the establishment of diplomatic relations, the conclusion of a minority treaty, a trade and customs agreement, and, the most horrendous possibility in the eyes of the Lithuanians, the deletion of Article Six in the Lithuanian constitution. Article Six claimed Vilnius as the capital, and left the designation of a provisional capital to the legislature. On March 13, the government issued a statement accusing Lithuania of provocation and threatened measures appropriate to the situation. On Monday March 14, the Polish Senate called for the establishment of relations and the renunciation of Vilnius.

The Lithuanians had taken cognizance of developments, especially in light of the sergeant's remarks on the Varėna bridge, and the statements made by the Polish government, press, and public. Therefore, on the night of March 14-15, the Lithuanians presented the Poles with a proposal, informally transmitted by Leon Noël, France's envoy to Warsaw: A mixed commission would investigate the matter and present its findings to both governments. No response from the Polish government regarding this offer was forthcoming.

The conference which Beck had requested in Sorrento took place on the night of March 16-17, soon after his return to Warsaw. Beck's account of the discussions is very useful:

"At the Royal" Castle I summed up the situation as follows: I repeated my general opinion of the situation and added that in view of order and peace being shattered [sic] in eastern Europe the neighborhoods of a country which refused to have normal diplomatic relations with us became a danger. A frontier incident could under present conditions be treated very seriously indeed, as it was a period when one could easily expect far greater complications. If we put our demand to Lithuania in a very steadfast way then the general tension in European affairs would but stress our move. If our demand was put with a moderate aim and without violating any genuine interests of Lithuania then we would have a fair chance to have them accepted and further to relieve the tension very quickly. In view of the above I proposed to the Government to give our move the form of an ultimatum, but only to demand that normal diplomatic frontier and neighbor relations be established without complicating our demand by any additional conditions. All those present at the Royal Castle immediately accepted my conclusions with the exception of Deputy Prime Minister Kwiatkowski who as usual was afraid of any serious decision. Although I considered that there was a maximum chance for a peaceful settlement of the matter, i thought it my duty to appeal to Marshal Smigly-Rydz by indicating that if we had to threaten, then we should have at least a minimum of means at hand to carry out our threat. Marshal Smigly-Rydz in the first instance ordered the Vilno garrison to be in readiness, and further, I think, pressed by Minister of War General Kasprzycki, prepared for further military arrangements with a view to being able to undertake full military operations in a short time if necessary. When in our ultimatum we had to put a term on which the Lithuanian answer was to be given, I have to admit that I let myself yield to a sentimental argument and extended it for a further twelve hours so that the final date became that of the 19th March, St. Joseph, the name day of Marshal Pilsudskį."17 Beck's account leads one to believe that he assumed a moderate stance with regard to the Lithuanian question. This would be a trifle self-serving and not exactly representative of the facts. Beck had never been afraid to exert pressure on Lithuania. While openly criticizing Kaunas for being intransigent, he had in fact himself sabotaged an accommodation. In the previous year, persecution of Lithuanians in the Vilnius territory had increased. According to the U.S. envoy in Kaunas, "of late Poland has become more impatient and various remarks issuing from official sources have had a martial ring. For instance, Mr. Beck stated in rather ominous tones: 'Lithuania had better take care or we shall take the border situation seriously.' This remark was made late in 1937. In light of such attitudes and several border incidents that were clearly of the provocative type, one is not certain that the present incident which brought on the ultimatum could not have been of provocative character."18

Beck also utilized pressure within Lithuania itself, taking advantage of the volatile domestic situation to agitate for normalization of relations with Warsaw. He was definitely carrying on the methods and traditions of his former mentor, Pilsudskį. His so-called moderation went hand-in-hand with Polish troop movements.

In assessing the response to Lithuania, Beck was viewing Poland's position in the European schema. He had been watching the growing power of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. His "Baltic policy," which was never realized, envisioned the construction of a Warsaw-dominated Polish-Baltic-Scandinavian bloc free of Soviet or German influence. The Vilnius dispute had always been a key obstacle to the fulfillment of this policy. Without Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia would never join such an arrangement, especially in light of the Baltic Entente Cordiale of 1934. The construction of the Baltic bloc appeared more urgent now than ever before. Germany was an ever-growing menace and Beck knew full well that it had its eyes on Poland. Now was the time to mend ties with Lithuania using force if necessary. One who witnessed firsthand the foreign policy of the Germans was Poland's ambassador to Berlin, Jozef Lipski. He commented that the ultimatum to Lithuania "was dictated by our desire to shield ourselves in that region against Germany."19

The ultimatum in its final form was completed by Beck on the evening of March 17. First, it formally rejected the Lithuanian proposal for an investigatory commission. Then it demanded that Lithuania restore diplomatic relations with Poland, dispatching an envoy to Warsaw and accrediting a Polish envoy to Kaunas by March 31. A reply was expected in forty-eight hours "without alterations, supplements or reservations." Silence would be interpreted as a negative response. If Lithuania were to explicitly or implicitly reject the Polish note, Poland would "guarantee her state's interests by her measures," obviously referring to military intervention. The note was accompanied by a supplement: the draft text of a response that the Lithuanians should use. Beck then telegraphed the note to the Polish envoy in Tallinn, Waclaw Przesmycki, instructing him to write, sign, and deliver it to Bronius Dailidė, the Lithuanian minister in the Estonian capital. The note was delivered to Dailidė at 9 P.M.20

Dailidė promptly telephoned the foreign ministry in Kaunas and recited the ultimatum to Foreign Minister Stasys Lozoraitis, Sr. He had recently returned from Zurich, where he had been visiting the ailing Prime Minister Juozas Tūbelis. Lozoraitis himself wrote down the text.21

Domestic reaction on both sides was swift and predictable. The Lithuanian populace was called upon to prepare for the defense of the nation. Armed men and elderly national guardsmen patrolled the shores of the Merkys. Polish domestic agitation, stirred by the OZN, received an impetus in the ultimatum. The atmosphere in Poland was well-described by the American ambassador in Warsaw in his cable to the Secretary of State forty-five minutes before the delivery of the ultimatum.

"Since occurrence of border incident (Friday, March 11) public opinion throughout Poland has been whipped up to a high pitch both by pro-Government and opposition press, in fact I perceive that the momentum of feeling favoring Poland's obtaining full satisfaction has reached a point whereat public opinion would favor even military action against Lithuania . . .

Pro-Government press in playing up situation has afforded the Government promises for national unity and an opportunity to capitalize situation; indeed, in my opinion, achievement by Poland of her objective: resumption of normal Polish-Lithuanian relations and Lithuania's recognition of territorial status quo would be interpreted here as a victory which in terms of internal political considerations would undoubtedly serve [the Government] handsomely. ""22

In the occupied region, the families of Polish military men began to leave for Poland in anticipation of war. Beck dispatched Marshal Smigly-Rydz to Vilnius to oversee military preparations. A, demonstrating crowd in Vilnius chanted, "Marshal, lead us to Kaunas!"23

As for the Lithuanian government, it was taken by surprise at the reaction to the shooting at Trasninkai and the method of establishing diplomatic relations. Even foreign diplomats were surprised. "The world is certainly cockeyed. An ultimatum is generally accompanied with the cutting off of diplomatic relations, instead of a demand for the resumption of diplomatic relations."24 Despite shock over the methods used, however, the Lithuanians should not have been surprised at the Polish goal. In fact, for a number of years close advisors of President Antanas Smetona, such as Prime Minister Juozas Tūbelis, Rev. Vladas Mironas, and Commander-in-Chief General Stasys Raštikis had been urging him to come closer to Poland and reach a modus vivendi regarding the Vilnius question.25 Unfortunately, Vilnius, as many diplomatic issues are, had always been entangled with national pride on both sides of the border. Kaunas was afraid that the establishment of formal ties with Warsaw would mean the renunciation of its claim to Vilnius. Most Lithuanians were in agreement with this line of thought. In fact, a favorite slogan was, "We will not rest without Vilnius."26

During conversations within the Lithuanian government, some officials were looking to the future of the country. For example, the Lithuanian minister in Moscow, Jurgis Baltrušaitis, feared "that if Poland's demands are met they will be followed by others which will impair Lithuania's sovereignty."27 Such attitudes were not surprising when viewed in the perspective of European militarism and instability. Hitler had just annexed Austria; many Lithuanians feared a Polish anschluss. Others alluded to World War I. They compared Trasninkai to Sarajevo. The Poles had issued an ultimatum in the same fashion as the Austrians had done to Serbia after the Archduke was assassinated. The chain reaction which led to the 1914 conflict could be duplicated now. Trasninkai might flare up into World War II.

FOREIGN OPINION

Upon receipt of the ultimatum, Lithuania began acting on the foreign front. Representatives in Kaunas were called in and advised of the situation. Advice was sought in foreign capitals. In every case, the Lithuanians were told to accept the ultimatum, although the British and French agreed to make an attempt to moderate Polish demands. They had always called for a "consolidation" of the political situation in that region of Europe.28 In the face of Hitler, diplomats did not want to contend with yet another, relatively minor, problem on the continent one which could prematurely ignite a major conflict. The League of Nations even went to the length of telling Lithuania that she must accept the ultimatum, lest the matter provoke intervention by the League;29 It was a rather bombastic statement considering the fact that the League had not been regarded as having great import in European affairs.

The Baltic neighbors to the north, Estonia and Latvia, had always made it known to Lithuania that diplomatic relations between her and Poland would be "highly desirable."30 The deadlock between the two nations had hindered Estonian and Latvian relations with both countries. It was a detriment to Baltic security and stability between Germany on one side and the Soviet Union on the other. The final resolution of the Polish-Lithuanian dispute would strengthen the Baltic position.

The British government and press deplored the ultimatum and hoped that wider demands would not follow. However, on Friday March 18, exactly one week after the incident at Trasninkai, the British informed the Lithuanians that "her government . . . advised Lithuania to accept Poland's ultimatum, adding that it could bear no responsibility in case the ultimatum were rejected."31 Eventually, when the ultimatum was accepted, the British expressed relief at the peaceful resolution of the crisis.

Across the channel, the French government took a more activist role on behalf of Lithuania, with which she had cordial relations. The Lithuanian foreign ministry instructed its envoy in Paris, Petras Klimas, to seek France's intervention in persuading the Poles to rescind the ultimatum. At that time, Lithuania declared to French officials that she was willing to begin negotiating the establishment of relations.32 The Quai d'Orsay expressed "strong action" in Warsaw on behalf of Lithuania. However, the Poles informed France that the ultimatum would not be withdrawn. Although the French lent a sympathetic ear, they expressed happiness that the matter was ultimately disposed of peacefully. The French position was supported by the logic of Ambassador Noel in Warsaw, who later wrote that Beck wanted "absolute Lithuanian capitulation or war."33 French Foreign Minister Paul Boncour was glad that the affair ended without "catastrophe." He expressed to Klimas that the "[crisis] had been more serious than is thought." He was one who felt that Trasninkai could have led to World War II. Bouncour was, however, surprised at the Kremlin's inaction and seeming lack of concern. He speculated whether the Soviets did not care about what happens to Lithuania or if they had become weak in European politics.34 After the conclusion of the crisis, Klimas would express his thanks to Boncour for his assistance and sympathies.

In Warsaw, the Poles were dismayed and angered by the attitude of the French. Poland suspected that French friendliness toward Lithuania was for the purpose of guaranteeing for the Soviets a corridor to East Prussia in the event of a German attack on France.

The Poles, while thankful for the moderate approach of the British, particularly resented the intervention of the French. French policy, declared Kurjer Poranny on March 23, had actually hindered "Polish-Lithuanian understanding," because French newspaper reports had served to stimulate anti-Polish sympathies in Lithuania.35

The Polish envoy in Paris, Juliusz Lukasiewicz, lamented the "deplorable conduct of French diplomacy."36

As opposed to the British and French, the Germans had a vested interest in Lithuania, namely, Klaipėda (Mėmei). While Ribbentrop advised Lithuanian envoy Jurgis Šaulys to be "realistic" and accept the ultimatum peacefully, he was also preparing for the opposite response. By noon on March 18, "Case Mėmei" directions were complete and units were massed in East Prussia along the border with Lithuania. If the ultimatum were rejected and the Poles were to respond with force, the Reich was prepared to invade and occupy Lithuanian territory to the north and west of the Nemunas River up to the Dubysa, including Raseiniai, Kražiai, Varniai, Rietavas, and the Klaipėda territory.37

The Germans were worried that Polish action in Lithuania and the Reich's moves into Klaipėda would entangle them with the Soviets. The Kremlin had warned Warsaw to respect Lithuanian sovereignty, adding that it considered an independent Lithuania vital to its interests. Jozef Lipski, Poland's ambassador in Berlin, assured Goering, the acting head of state during Hitler's visit to Austria, that while the void in Polish-Lithuanian relations "threatened serious consequences at any moment," Poland did not foresee any danger from the East, and that furthermore, she was bringing such risk on her own shoulders.38

While assessing the present, Ribbentrop was also looking to the future, when the Reich would turn its gaze eastward. A potential scenario, whereby Lithuania would be turned over to Poland in exchange for the Danzig corridor, was now endangered; the object of compensation would be removed if the Poles were to occupy it now.39

Despite Nazi intentions and motives, the widely reported collaboration between Germany and Poland is refuted by Lipski. In the eyes of many, the uncanny coincidence of Anschluss and ultimatum further coinciding with troop movements by both sides had to be connected. Investigations have not yielded evidence to substantiate this claim. Beck's hopes of a neutral Polish-Baltic-Scandinavian bloc would not mesh with joint Polish-German maneuvers. It is also doubtful whether Hitler would have wanted to engage in major action so far east so early. For example, in 1939, Hitler's ultimatum to Lithuania was just for the Klaipėda territory nothing more. Nonetheless, the "conviction [of Polish-German collaboration] contributed to a large extent to Kaunas' acceptance of the Polish ultimatum."40

Yet, it must also be mentioned that the Germans were sympathetic to the Polish point of view. On March 16, Lipski and Goering met. It was at this meeting that Goering raised concerns over the security of German interests in Klaipėda.41 In response to this query, Lipski cabled for instructions to the Polish Foreign Ministry. Warsaw replied that if a Polish-Lithuanian conflict ensued, German interests in Klaipėda would be respected by the Poles.42 The Germans also exerted concrete pressure on Lithuania. During the crisis, they held up a routine machinegun shipment to Lithuania from Czechoslovakia while in transit.43

Meanwhile, Ribbentrop counseled Šaulys that Lithuania would never receive the hoped-for aid from the Soviet Union. According to the German foreign minister, " 'the Polish terms were very moderate and ... we could only advise unconditional acceptance of the Polish proposal.' "44 Afterwards, Ribbentrop advised Lipski that he felt the Lithuanians would peacefully accept the ultimatum.

In the east, the Soviets were monitoring the situation closely. Almost three months prior to the Trasninkai incident, on December 24,1937, Stalin had summoned a Government council at the Kremlin. Apparently, two conclusions were reached. First, the Soviet Union could not hope to successfully wage war on two fronts. Second, the immediate outlook indicated that Japan posed a greater threat to the Soviets than Germany. As a result of the meeting, attacks on Germany through the press, radio, and other means had been toned down since January of 1938. It was the opinion of the American envoy in Warsaw that the Poles had known of the Kremlin conference.45 In other words, the scenario painted was that the Soviets were looking to Japan as a threat, and had thus tried to stabilize their situation in East-Central Europe. This implied that they would not commit troops in that area unless absolutely necessary. Such a policy would give the Poles more latitude with Lithuania.

The diplomatic corps in Moscow was growing more excited. It was here that rumors of Polish-German collaboration were strongest. According to those rumors, the Reich would give Klaipėda to Poland in exchange for Danzig. Concomitant with this exchange, Germany would compensate Poland for her expenditures on the port of Gdynia, and would make peacetime arrangements for free port facilities for Poland through Danzig and Gdynia. There were those in the Soviet capital who thought that Moscow would come to Lithuania's aid. This would ultimately lead to a full-scale conflict. One of those counting on such aid was Jurgis Baltrušaitis, the Lithuanian minister in Moscow. According to his logic, Soviet interests would be affected if Lithuania were to be placed in any danger. Despite the Kremlin's strong rhetoric, however, it was the opinion of Joseph Davies, the American envoy there, that "the Soviet Government will not embark upon a war single-handed with Poland and possibly Germany and Japan to save Lithuania."46

As for the Soviet position vis-a-vis Poland, Soviet Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov advised the American envoy:

"(1) That he had sent for and had three discussions with the Polish Ambassador; and that he had impressed on the latter the grave seriousness with which the Soviet Union regarded this ultimatum;

(2) That the Soviet Union was not concerned with what the relations between Lithuania and Poland were; but that it was vitally concerned with the fact that Lithuania should actually be and continue to be independent;

(3) That his government was concerned lest still more serious demands should be made by Poland if Lithuania should accede to the present demand, under some similar "innocuous dress" which would in effect destroy Lithuanian independence."47

Litvinov used the term "innocuous dress" to characterize the form of the ultimatum. The mere resumption of diplomatic relations appeared on the surface to be a quite reasonable request. If it were refused, Lithuania would lose any foreign sympathy it could have hoped to gain. Of course, this was ignoring the Vilnius question. The Poles had not even mentioned this in their note. A Lithuanian refusal would not be on the basis of the "innocuous" resumption of relations, but on the principle of sovereignty over Vilnius. This skillful political and linguistic manipulation by Beck placed the Lithuanian government in an uncomfortable position in terms of world opinion.

Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister V. P. Potemkin told Polish representatives that if Poland were to attack Lithuania, the Kremlin would abrogate the 1932 Polish-Soviet non-aggression pact and "have a free hand" in the matter.48 At a press conference for foreign correspondents, Litvinov lashed out at a member of the Polish news agency:

"Your government says it did not address an ultimatum to Lithuania, but it smells like one to me. If you say the situation is not serious I hope you are right; but it looks serious to me. We informed your government in the friendliest manner about our anxiety over this point."49

In response to Soviet protests, Polish officials replied that they demanded only diplomatic relations; no force was intended. This was, to say the least, an incredible statement, since it was well known that Polish troops were massing on the border.

Despite Soviet polemic, Moscow advised Kaunas to peacefully accept the ultimatum, even though Warsaw-Kaunas discord had always been a component of the Kremlin's foreign policy. This shattered Baltrušaitis who, according to Davies, was "heartbroken."50 Colonel Kazys Skučas, the Lithuanian military attache in Moscow, reacted more bitterly, telling his German counterparts that Lithuania was now paying for having previously refused Soviet offers of assistance and cooperation in foreign and military affairs.51

It is to military affairs that we now turn.

THE MILITARY FACTOR

Of course, the ultimatum would not have been heeded in much the same way had the Polish government not backed up its demands with concrete action. The movement of men and materiel by three Eastern European countries caused consternation on the part of European diplomats, who feared that the regional matter would spill over onto the rest of the continent. The Polish military desperately wanted to flex its muscle against Lithuania. The Vilnius question had become a matter of pride, and high-ranking officers in Warsaw wanted to triumphantly conclude the matter, especially in the wake of Trasninkai. Likewise, on the other side of the administration line, pride had infected soldier and civilian alike. Not only was the army placed on alert, but elderly national guardsmen, many of them veterans from the wars of independence twenty years earlier, also patrolled the shores of the Merkys along the frontier.

Polish forces were placed on an increased state of readiness (na ostrym pgotowiu). The Poles massed approximately fifty thousand troops along the line. Four divisions, including armored vehicles, were involved. Two divisions, one from the Warsaw I Corps, the other from the III Corps, were moved into position in the Vilnius region prior to the presentation of the ultimatum. They went near Rykantai, which is found between Vievis and Lentvaris. The division from I Corps had been sent to reinforce the III Corps, which was ordinarily stationed in Vilnius, Gardinas, Suvalkai, Lyda, and their regions. The III Corps consisted of three infantry divisions, two cavalry brigades, six battalions from KOP, and two squadrons. Two air force regiments, consisting of about one hundred aircraft, were concentrated outside of Vilnius and Lyda. The Polish fleet was reportedly sailing northeast in the Baltic to go on station close to Lithuanian shores.52

As the Poles were finalizing their military preparations, the Germans were making "Case Mėmei" operational. Hitler issued a directive to the German armed forces on March 18 to prepare plans for the occupation of the Klaipėda territory. The I Division in East Prussia was placed in a state of readiness. Approximately one thousand men from the SS and SA were on alert in Tilsit. Warships were assembling at the port of Piliau and the Luftwaffe was observed over the Klaipėda region. If the Poles were to march into Lithuania, the Germans would immediately occupy Klaipėda and surrounding regions. Interestingly, the Lithuanian military attache in Moscow, Colonel Skučas, had been told that Germany would enter Klaipėda by Major General Ernst Koestring, the German military attache in Lithuania and the Soviet Union.53

Looking to Lithuania, one saw a situation marked by a lack of activity. The Lithuanian army engaged in no serious movement or preparation for combat. There was neither a call-up of the reserves, nor a partial mobilization. Components of the military were informed of possible action. However, it should be noted that the army was on alert during the ultimatum crisis and ready to move and fight if so ordered. Polish demonstrations in the Vilnius region and Poland were closely monitored by the military. Lithuania, according to General Stasys Raštikis, could have mobilized 250,000 men. However, it was only planned to call 120,000-135,000 reservists in case of emergency. Lithuanian wartime plans called for four strong divisions, two brigades, and various supporting components. While the military had faced a shortage of funding and weapons, decentralized mobilization could have reputedly been accomplished in 24 to 72 hours.54

The Lithuanian military was also hindered by deep-rooted, long-term foreign policy considerations in the Baltic. The Vilnius and Klaipėda problems placed obstacles to cooperation with Latvia and Estonia, despite the Baltic Entente of 1934. Riga and Tallinn were thus provided with a convenient excuse not to enter into a military arrangement with Kaunas.

Information regarding the Red Army during the crisis is scanty and ambiguous. The German minister in Estonia, Frohwein, reported on March 16 that "troop movements had been observed lately at Soviet Russia's western border." Yet, the Polish government reported to French ambassador Noel in Warsaw that Soviet troops were not concentrated near Poland's southeastern border. Furthermore, the head of the Baltic Department in the Soviet Foreign Affairs Commissariat informed a Finnish diplomat that the U.S.S.R. would take no action if Poland attacked Lithuania.55

What then? Even if the Soviets had come to the aid of Lithuania, it is doubtful whether they would have taken it upon themselves to prematurely ignite World War II by engaging the Wehrmacht. Despite Litvinov's rhetoric, despite speculation to the contrary, despite probable Soviet short-term interest in an independent Lithuania, the Russians would not have committed troops to a campaign against the Poles. Even the Russophile Baltrušaitis ultimately came to this conclusion. The Soviets had little to gain by fighting Warsaw; regardless of who occupied the Vilnius territory or Lithuania the Kremlin would have eventually dealt with them on its own terms.

Despite indications that morale was high, both within and without the Lithuanian military establishment, even statistics show how weak Lithuania was relative to the activity taking place in Prussia and Polish-occupied territory. Lithuania hoped for four strong divisions during hostilities; Poland was deploying that much strength just in its mobilization operations during the crisis. The addition of German forces placed Lithuania at a further disadvantage. The Poles assembled one hundred aircraft in the Vilnius region, whereas Lithuania possessed that many aircraft in its entire air force. Finally, the Polish and German fleets were assembling in the Baltic; Lithuania had only one major warship, the Smetona, guarding the port at Klaipėda. It is clear that Lithuania would, indeed, have been hard-pressed to defend her independence against Poland and certainly could not have withstood an assault on two fronts involving Germany. The state of the Lithuanian military most likely played the decisive role in the government's decision to accept the ultimatum.

Had Lithuania not accepted the ultimatum, Hitler saw the Poles as being ready to fight "at the drop of a hat."56 The American embassy in Warsaw had discerned from its sources the following likelihood: Polish forces would advance about one kilometer into "no-man's land" along the administration line. If the Lithuanians were still intransigent after this show of force, troops would advance further into Lithuanian territory.57 Contrary to the opinion held by the foreign ministry, the Polish military felt that Lithuania would fight.58 The Lithuanian government was to prove the foreign ministry correct.

RESOLUTION: THE LITHUANIAN DECISION

The Lithuanians faced disadvantageous positions in terms of world and diplomatic opinion, and the military factors. These considerations prevailed despite the high morale and willingness to fight of the people and soldiery. The ultimatum had been delivered on Thursday March 17, six days after Trasninkai. Lithuania had only forty-eight hours to respond. Therefore, a meeting took place on the night of March 18-19 at the Presidential residence on the outskirts of Kaunas.59 President Antanas Smetona presided. In attendance were the Cabinet, under the leadership of Acting Prime Minister Jokūbas Stanišauskis, substituting for the ailing Prime Minister Juozas Tūbelis; the president of the Seimas, Konstantinas Šakenis; the Army Chief of Staff, Brigadier General Jonas Černius; and Commander-in-Chief General Raštikis. The meeting was tense and nervous.

Most of the participants took the sober attitude that while the honor of Lithuania may be soiled by the peaceful acceptance of the Polish demand, it was a more welcome prospect than occupation at the hands of the Polish military. However, the Minister of Agriculture, Stasys Putvinskis, was very agitated during the gathering. He angrily stated that the honor of the nation had been insulted and that it must now be "satisfied;" force must be met with force. Acting Prime Minister Stanišauskis was also agitated. However, neither he nor Putvinskis put forth any concrete proposals. Most probably, they had also conceded, at least to themselves, that Lithuania had no recourse other than acceptance.

Foreign Minister Stasys Lozoraitis announced the results of the feelers put out to foreign diplomats. He stated that all had urged Lithuania to peacefully accept the ultimatum. He also took the occasion to subtly chide the government for its long-standing obstructionist position regarding the establishment of ties with Warsaw. Lozoraitis felt that the embarassing and dangerous situation in which Lithuania now found herself could have been avoided.

General Raštikis was called upon to speak. He was highly respected in both military and civilian circles. He had risen to the post of Commander-in-Chief in 1935 at the youthful age of forty, while still holding the rank of colonel. In addition, his wife was President Smetona's niece Anything that Raštikis said would certainly be thoughtfully considered. It had long been the opinion of high-ranking army officers that relations with Warsaw should be restored. They felt that the enemies of Poland and Lithuania were the same; therefore, a mutual defense could be quite effective and highly desirable. A modus vivendi without formally renouncing Lithuania's claim to Vilnius would be the ideal situation.

Raštikis was of the opinion that Lithuania could not fight Poland alone. In addition, the military was not prepared for combat. Only three years of his seven-year military reorganization and strengthening program had been completed. Raštikis reminded the participants that the president, the prime minister, and the Defense Council had previously accepted his request not to draw the army into armed conflict with a major power without the assistance of allies; it was apparent that no allies were placing themselves at Lithuania's disposal.

Raštikis concluded his presentation with four points. First, Lithuania cannot fight Poland alone. Second, if necessary, the army can attempt a defensive posture or even a show of force. Third, if ordered, it will engage the enemy. In that case, there should be no illusions of a successful outcome. Fourth, the army recommends a peaceful settlement of the matter.

After further lengthy discussions, it was decided to establish diplomatic relations with Poland. The government had no choice but to accept the ultimatum. It was overwhelmed militarily, did not have the support of foreign diplomats, had no forthcoming allies, was under pressure to "consolidate" the region, and was afraid of igniting a continental conflict, which could prove even more disastrous for the tiny, embattled country. Most importantly, independence was in a precarious balance. The government had also come to the conclusion that ties would not imply the renunciation of the claim to Vilnius.60

After the meeting, the foreign ministry contacted Dailidė in Tallinn and instructed him to commence the exchange of notes with Przesmycki.

An extraordinary session of the Seimas was ordered for Saturday, March 19 at 12:30 p.m. at which the acting Prime Minister solemnly read the Government's answer to the Polish ultimatum. The Seimas received the word of the Government with silence and then very briefly accepted it with only one addition: "that we accept because of force."61

AFTERMATH

On the day of acceptance, Jozef Lipski and Jurgis Šaulys had a "friendly conversation" in Berlin. Lipski was to write, "this day of March 19 was a day of great satisfaction for me." Joseph Davies held a reception for the diplomatic corps that evening in Moscow. He reported that the Polish envoy greeted Baltrušaitis with an "effusiveness" noticed by the others.62

The Polish government officially replied on Sunday March 20, assuring the new Lithuanian legation in Warsaw "all conditions of normal activity." Colonel Kazys Škirpa was appointed on March 26 as Lithuanian minister to Poland. Colonel Aloyzas Valusis, President Smetona's son-in-law, was named military attache. The Poles acquired a villa in Kaunas and sent Fr. Chorwat as minister to Lithuania. Colonel L. Mitkiewicz was appointed military attache.

Of course, beside the formal diplomatic exchanges, the more mundane business of communication and transportation had to be ironed out. The first conference to deal with these matters was held in the southern Lithuanian town of Augustavą, under Polish occupation, on March 25-28. By the start of June, three conventions dealing with the opening of railroad and postal communications and river navigation had been concluded. Negotiations regarding aerial communication and a commercial treaty were already underway. Gradually, railways and roads at the administration line were repaired and built. As the year progressed, negotiations and agreements touching on a variety of issues had occurred.63

This progress, though, was not substantive as it was technical. The Poles were glad that basic intercourse had been restored, but they felt that the Lithuanians were not cooperating in matters of greater import. While Beck wrote that Polish-Lithuanian relations "followed a new and creative direction"64 after the establishment of ties, Warsaw was not pleased with Kaunas' sluggishness and used pressure to gain concessions.

Beck was able to take personal advantage from the ultimatum's acceptance. His prestige, despite some domestic grumbling that more dramatic action had not been taken, was enhanced. He could now present to the world a more stable situation in the Baltic the type of situation diplomats had been hoping for and the impression of a prouder, stronger Polish eagle. Indeed, Lozoraitis commented that Beck appeared to have the mindset of a minister of the Empress Maria Theresa. Both personal and national prestige played roles in this disposition.65

The post-ultimatum events on the other side of the administration line developed in a different, more confrontational manner. The people in the vicinity of Trasninkai did not take the news very well. Many Lithuanians felt that Vilnius had been abandoned. Demonstrations took place in several localities. On Sunday March 20 at the State Theater in Kaunas, journalist Justas Paleckis stood up during the intermission of a performance of "Samson and Delilah" and demanded the resignation of the government. He was arrested on the spot, but released the next morning. The next evening saw a crowd gather on the grounds of the War Museum at 6:00 PM. The popular General Vladas Nagius-Nagevičius spoke on behalf of the government. The secret police, however, allowed no other speakers, who would presumably have been of the opposition. Many then sang patriotic songs and marched through the streets, passing the Cabinet building. The demonstration lasted until about 10:00 PM, despite the use of clubs and tear gas by the police. Martial law was declared in the capital.

The Government had clamped a very strict censorship over the press and all other mediums of communication. The opposition groups, however, had at first offered their complete cooperation to the Government for the best interests of the fatherland.

Following the acceptance of the Polish demands, the opposition went into action. Meetings were held secretly and various agreements were reached and policies formulated. The opposition groups [were] drawn from the People's Socialist, Christian Democrat, and the Social Democrat groups . . . Copies of [their] resolutions were immediately confiscated by the police and military and only a few reached those for whom they were intended.

There was very little demonstrating due to the fact that the Government in power (Nationalist) had strictly forbidden it as inimical to the welfare of the State. It was enforced with a full use of the police and military. Sporadic attempts by student groups and certain classes of laboring people were efficiently handled.66

An example of opposition demands is found in a resolution of the Lithuanian Democratic Front Croup, which called for a new coalition government, the dismissal of the "falsified Seimas," the election of a new Seimas, and presidential elections. Another resolution signed by the two former presidents one of whom had been ousted in the coup d'etat of 1926 former prime ministers, ministers, the vice-president of the third Seimas, a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, and the pro-rector of the University of Vytautas the Great was issued.67

It stated:

"According to our belief the establishment of normal relations with Poland was and is in the interest ... of Lithuania; however, we understand that the manner in which these relations were renewed is not worthy of the great and honorable past of our nation which was guided by Vytautas the Great.

During the course of eleven years the present Government has had many convenient and favorable opportunities to renew normal relations with Poland in an honorable manner. The present Government, in its foreign policy, has failed to show the necessary sagacity, as well as a deep conception of international situations and has given to Poland the opportunity to make use of the situation in a manner which is dishonorable to Lithuania. The painful form of the ultimatum presented to the Government was painfully felt by the whole nation . . .

A humiliated Government cannot represent Lithuania and protect its problems. Only a new Government, representing all loyally minded groups and organized on a coalition basis, could be in a position to unite the nation in the presence of danger, to tighten it together for uniform activity, to increase its power and to prepare it for a strong resistance against expected heavy tasks."68

On March 24, after alarmingly mounting pressure, the Tūbelis cabinet resigned. Smetona called upon Rev. Vladas Mironas to form a new cabinet. Opposition groups were not satisfied with this move. The Cabinet was still controlled by the Nationalists; it had merely undergone a facelift. President Smetona thus still feared a coup by dissatisfied, young army officers. The secret police remained on alert. Lozoraitis, who had resigned along with the rest of the Tūbelis cabinet, was asked by Smetona to remain as Acting Minister of Foreign Affairs. He remained at that post until December 5 of that year. In an attempt to placate the people, the new Constitution, which was promulgated a month and a half later on May 12, retained the sixth article, which claimed Vilnius as the capital.

Switching from domestic to international issues, officials on both sides professed to be pleased with the newly-forged links. Of course, relations were measured not so much on the basis of goodwill, but on their instrumental value to both sides. For example, in October, 1938, the Germans placed pressure on Lithuania with regard to Klaipėda. The Poles forced further improvement in relations by pressing Lithuania at the same time. On the other hand, by June of 1939, Lithuania had received a secret non-aggression pledge from Poland.69

One month prior to that on May 8, General Raštikis paid a visit to Marshal Smigly-Rydz for the purpose of broadening friendly relations and to officially announce a declaration of neutrality in the event of a Polish-German conflict. The Marshal awarded Raštikis the Order of Polonia Restituta (First Degree).70 While en route to Riga, Beck was allowed to land in Kaunas for a half-hour. He received "the very best impression" from Foreign Minister Juozas Urbšys.71

Despite the seeming improvement in relations, including the possibility of a joint declaration on minorities, the treatment pf Lithuanians in Vilnius remained a bone of contention. In the autumn of 1938, at the demand of the Poles, the Lithuanian government closed the offices of the Vilnius Liberation League, which had operated in Lithuania since the Polish takeover. The last remaining Lithuanian school in Vilnius was closed by Polish authorities. New organizations were not allowed to be established; old ones were not permitted to reopen. Only the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences was permitted to renew activities although it had to alter its by-laws. The property of closed organizations, which had been administered by trustees of the Polish government, was auctioned off.

In foreign affairs, new possibilities were opening up. On the one hand, analysts were stating that Finland and the Baltic were now more cognizant of the importance of maintaining good relations with the Soviet Union in order to offset Poland and Germany. On the other hand, observers pointed out that Polish-Lithuanian relations now allowed the formation of a Balto-Polish block to counter Moscow and Berlin, especially in light of German pressures over Klaipėda.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

British radio described the first weeks of March, 1938 as a period of "most serious intensity and horror" on the continent. The Polish-Lithuanian crisis was a component of that intense and horrible period, one of the opening acts of the drama later to be known as World War II. Diverse analyses abounded after the crisis. Lozoraitis claimed that Poland had had opportunities for peaceful settlement of the dispute, either through the League of Nations or a third party. According to him, this incident had not been the first of its kind in European history; precedents and adjudicatory procedures existed. Lozoraitis also points out that no state has the legal obligation to enter into relations with another, neighbor or not, especially by threat of force. He writes that lack of ties with Lithuania did not threaten the security or vital interests of Poland, taking into account the disproportionate populations, military potential, and territory. Finally, he affirms that Lithuania had no secret agreement with the Soviet Union or Germany, labeling such speculation as "pure nonsense." If the Soviets and Poland were to fight, Stalin would not elicit the support of the Baltic States he would merely occupy them. Hitler likewise had designs in the Baltic. In any case, the existence of diplomatic ties does not guarantee security.72

General Raštikis would later complain that the politicians had not paid enough attention to the needs of the military, had not expended the necessary resources to maintain it as an effective deterrent. This was especially dangerous in light of the government's policy of brave politics and verbal confrontation. He regretted that the Polish-Lithuanian situation had deteriorated to to the point where Poland said, "Love me, otherwise I will stab you."73

In Moscow, Colonel Skučas would report at the end of March that "small states are once more given a lesson that, while living among great ones, their own strength is not enough for maintaining their independence and defending their interests; they need support from one or several great powers to this effect ... I deem it my duty to remind that under the circumstances it might be useful to seek for such support in Moscow."74

Perceptive observers, while lamenting the humiliating method by which "the Polish government took advantage of [Lithuania's] misfortunes to settle old scores and to indulge in a bit of bombastic self-congratulation,"75 also realized that the rejection of the ultimatum would have meant the loss of Lithuania's independence at the hands of Poland and Germany. Lithuania would not have received any aid since the world was too preoccupied with the relatively more important twists in Austro-German relations.

Finally, projections on the outcome of World War II have been put forward. For example, had the Poles or the Lithuanians done one of several things, alliances might have been forged which would have altered the outcome of the war. Therefore, we would see a different map of Europe today.76

** The author acknowledges Dr. Thomas Remeikis of Calumet College, Indiana. Dr. Alfred Erich Senn of the University of Wisconsin at Madison, and Dr. Corey B. Venning of Loyola University of Chicago for their advice, assistance, and support during various stages of the preparation of this essay.

* Robert A. Vitas is a graduate research assistant in the political science department at Loyola University of Chicago.

1 Owen J. C. Norem (U.S. Minister to Lithuania 1937-1940), Timeless Lithuania (Chicago: Amerlith Press, 1943), pp. 149, 196.

2 Norem, p. 197.

3 Regina Žepkaitė, Diplomatija imperializmo tarnyboje: Lietuvos ir Lenkijos santykiai 7979-7939 (Diplomacy in the Service of Imperialism: Lithuanian-Polish Relations 1979-1939), ed. S. Noreikienė (Vilnius:

Mokslas, 1980), p. 250, in Alfred Erich Senn, "The Polish Ultimatum to Lithuania, March 1938," Journal of Baltic Studies, XIII (1982), 144.

4 Andrius Ryliškis, Fragmentai iš praeities miglų: Atsiminimai (Fragments from the Hazy Past: Reminiscences) (Chicago: n. p., 1974), I, 387.

5 For instance, see Petras Mačiulis, Trys ultimatumai (Three Ultimatums) (Brooklyn:

Darbininkas, 1962), pp. 12, 35.

6 Jeronimas Cicėnas, Vilnius tarp audrų (Vilnius Amidst Storms) (Chicago: Terra, 1953), pp. 351-352. See also Mačiulis, p. 37; Aleksandras

Merkelis, Antanas Smetona (New York: Amerikos lietuvių tautinė sąjunga, 1964), 479-480; Ryliškis, p. 387; J. Žiugžda, ed., Lietuvos TSR istorijos šaltiniai (Sources on the History of the Lithuanian

SSR) (Vilnius: Valstybinė politinės ir mokslinės literatūros leidykla, 1961), IV, 666-667.

7 Senn, p. 144.

8 Senn, p. 144. Senn also states that initial Polish news reports were listed as having originated in

Kaunas, despite the fact that there were no Polish correspondents in the provisional Lithuanian capital. Subsequent news reports were date lined from other Baltic cities. See pp. 144-145.

9 Senn, p. 145.

10 U.S. Embassy, Moscow. Cable #74, Section 2, March 17, 1938, 760C.60M15/321 (Section 2) E/HC, p. 2. This and other unpublished U.S. State Department documents were provided through the generosity of Dr. Thomas

Remeikis, head of the political science department at Calumet College. The writer is grateful for access to this material.

11 Adolfas Šapoka, Vilnius in the Life of Lithuania (Toronto: Lithuanian Association of the Vilnius Region, 1962), p. 151.

12 Senn, p. 146.

13 Jozef Beck, Final Report (New York: Robert Speller & Sons, 1957), pp. 144-145.

14 Beck, p. 145.

15 Anna M. Cienciala, Poland and the Western Powers 1938-1939: A Study in the Interdependence of Eastern and Western Europe (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1968), p. 49.

16 Beck, p.145

17 Beck, pp. 145-146.

18 U.S. Legation, Kaunas. Despatch #103 (Diplomatic), March 25, 1938, 760C.60M15/360 G-J, p. 2.

19 Jozef Lipski, Diplomat in Berlin 1933-1939: Papers and Memoirs of Jozef Lipski, Ambassador of Poland, ed. Waclaw Jedrzejewicz (New York: Columbia University Press, 1968), p. 355. See also

Cienciala, p. 49; Šapoka, p. 149.

20 Senn, p. 149; U.S. Embassy, Moscow. Cable #77, March 18, 1938, 760C.60M15/327 E/HC, p. 1;

Norem, p. 150.

21 Mačiulis, pp. 11-12. Mačiulis discusses the reaction of foreign ministry personnel upon receipt of the ultimatum.

22 U.S. Embassy, Warsaw. Cable #22, Section 1, March 17, 1938, 760C.60M15/322 (Section 1) E/HC, pp. 1-2.

23 Ryliškis, p. 388; Stasys Raštikis, Kovose dėl Lietuvos: Kario atsiminimai (In the Wars for Lithuania: A Soldier's Reminiscences) (Los Angeles: Lietuvių

dienos, 1956), I, 516. Lozoraitis remarks that it would be difficult to envision any other military leader becoming involved in a civil demonstration, implying that Smigly-Rydz had lowered his professional military dignity as an officer. See Stasys

Lozoraitis, "Kelios pastabos Lenkijos ultimatumo klausimu" ("Several Observations on the Question of the Polish Ultimatum"), Aidai, (1976), No. 6, 252.

24 Joseph E. Davies (U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union 1936-1938), Mission to Moscow (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1941), p. 289, excerpt from diary: Moscow, March 16, 1938.

25 Vaclovas Šliogeris (Colonel, Military Aide to President Smetona 1935-1937), Antanas

Smetona: Žmogus ir valstybininkas: Atsiminimai (Antanas Smetona: Person and Statesman: Reminiscences) (Sodus, Ml: Juozas J.

Bachunas, 1966), p. 160.

26 This phrase was popularized by Petras Vaičiūnas, who wrote a poem with such a title. See Vaičiūnas, Amžiais už Vilnių dės galvą

lietuvis! (A Lithuanian Will Forever Die for Vilnius!), 2nd ed. (Kaunas: Vilniui vaduoti sąjunga, 1928), pp. 21-22.

27 U. S. Embassy. Moscow. Cable #77. March 18. 1938. p. 2.

28 Raštikis, I, 519.

29 Stasys Raštikis, Įvykiai ir žmonės: Iš mano užrašų (Events and Personalities: From my Diary), ed. Bronius Kviklys (Chicago: Akademinės skautijos

leidykla, 1972), III, 535-536.

30 Royal Institute of International Affairs, Information Department, The Baltic States: A Survey of the Political and Economic Structure and the Foreign Relations of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (London: Oxford University Press, 1938), p. 93.

31 See Kostas Navickas, The Struggle of the Lithuanian People for Statehood (Vilnius:

Gintaras, 1971), p. 99; U.S. Embassy, London. Despatch #99, March 26, 1938, 760C.60M 15/355 E/DC, p. 2.

32 See Albertas Gerutis, Petras Klimas (Cleveland: Viltis, 1978), pp. 144-145.

33 Raštikis, III, 537.

34 As will be seen later, the Soviets had expressed concern about the situation and had told the Poles not to aggress against Lithuania. Yet, Boncour had a good point in the statement regarding Moscow's weakness. One of the reasons it signed the

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1939 was to give itself time to prepare for war. In addition, the Stalinist purges of the mid-1930's had decimated the officer corps. The eventual Nazi successes in the first portion of World War II would reveal the imprudence of those purges. Therefore, relatively speaking, the Soviets were weak and wanted to delay hostilities for as long as possible in order to prepare for inevitable military operations.

35 Senn, p. 153. See also Cienciala, p. 50.

36 Juliusz Lukasiewicz, Diplomat in Paris 1936-1939: Papers and Memoirs of Juliusz Lukasiewicz, Ambassador of Poland, ed.

Waclaw Jedrzejewicz (New York: Columbia University Press, 1970), p. 97.

37 Documents on German Foreign Policy 1918-1945 (Washington: U.S.

Department of State, 1953), Series D (1937-1945), Volume V, 433, 437; Cienciala,

p. 51; Navickas, p. 98.

38 Lipski, pp. 353-354.

39 Documents on German Foreign Policy, series D, vol. V, p. 433.

40 Lipski, p. 352.

41 An interesting sidelight to the question of Polish-German collaboration emerges from this meeting. Goering proposed to the Polish envoy that Poland and Germany collaborate militarily against the Soviet Union. He stated that Warsaw would not be able to face the Kremlin alone. Aside from this, however, it does not appear that Anschluss and ultimatum were consciously coordinated in advance. See

Lipski, p. 354.

42 Lipski, p. 354.

43 U.S. Embassy, London. Despatch #76, March 23, 1938, 760C.60M15/354 E/DC, p. 3; Raštikis, III, 535.

44 Documents on German Foreign Policy, series D, vol. V, pp. 430, 433, 436.

45 U.S. Embassy, Warsaw. Cable #33, March 25, 1938, 760C.60M 15/351 E/HC, p. 3.

46 U.S. Embassy, Moscow. Cable #78, March 18, 1938, 760C.60M 15/332 E/HE, p. 3. See also U.S. Embassy, Moscow. Despatch #1074, March 26, 1938, 760C.60M 15/368

GMB, p. 3. This despatch is also reproduced in Joseph Davies, Mission to Moscow, pp. 292-295; Joseph Davies, p. 289, excerpt from diary: Moscow, March 17, 1938; Lithuanian Legation, Moscow. Despatch #15, May 12,1938. In this despatch Baltrušaitis discusses the events of the ultimatum crisis from his perspective. He also gives a chronological country-by-country diplomatic summary. It is excellent source material. The document was utilized during the deliberations of a high-level conference at the Foreign Ministry in Kaunas in the autumn of 1938. It was this conference which would opt for the policy of Lithuanian neutrality; Documents on German Foreign Policy, series D, vol. V, p. 442. (A complete translation of the Baltrušaitis despatch will be published in a later issue of this journal.)

47 U.S. Embassy, Moscow, Despatch #1074, March 26, 1938, p. 4. This despatch portended, coincidentally, the initial phase of the eastern theater of World War II. The following passage is excerpted from Davies' summary of the Litvinov conversation:

[Litvinov] stated that only the future would disclose what the real purpose of Poland was. He also stated that, which gave me [Davies] considerable surprise, in his opinion, Hitler was opposed to the absorption of Lithuania by Poland, for the reason that "Hitler was greedy for Lithuania and the Baltic States himself." In this connection he stated that Poland would get nothing out of her support of Germany and that "this is not because I say so, but it is the direct statement of the German military aid of the German Embassy in Moscow, which statement he made to me

[Litvinov] and at which time he also declared that Germany would very shortly take back the Polish Corridor and that Poland would get nothing therefor" (pp. 4-5).

48 V. P. Potemkin, ed., Istoriia Diplomatii (Moscow, 1945), III, 625, in

Cienciala, p. 52; Navickas, p. 98. Russian historians later claimed that it was Soviet threats of this kind that influenced Poland to seek a peaceful settlement.

49 Max Beloff, The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia: 1929-1941 (London: Oxford University Press, 1963), II (1936-1941), 123.

50 Joseph Davies, p. 289, excerpt from diary: Moscow, March 18, 1938.

51 Documents on German Foreign Policy, series D, vol. V, pp. 443-444.

52 The section dealing with Polish military preparations was compiled from the following diverse, and sometimes confusing, sources:

Navickas, p. 106; Raštikis, I, 516, 521; Raštikis, III, 537-538; Šapoka, p. 151;

Senn, p. 151.

53 Documents on German Foreign Policy, series D, vol. V, p. 433; Raštikis, III, 534.

54 Raštikis, III, 301; Raštikis, correspondence, Los Angeles, 2 August 1983; Vaclovas Šliogeris, "Lenkai,

ultimatumas, užkulisiai" ("The Poles, the Ultimatum, Secrets"), Tėviškei žiburiai, 12 September 1974, p. 2, cols. 3-7.

55 Documents Diplomatiques Francais 1932-1939 (Paris: Ministere des Affaires

Etrangeres, 1973), 2 Serie (1936-1939), Tom VIII (17 Janvier 20 Mars 1938), p. 931; Documents on German Foreign Policy, series D, vol. V, pp. 430, 442.

56 U.S. Embassy, Warsaw. Cable #33, Section 2, March 25, 1938, 760C.60M15/351 (Section 2) E/HC, p. 3.

57 U.S. Embassy, Warsaw. Cable #22, Section 1, March 17, 1938, p. 4.

58 Raštikis, I, 521. In May, 1939, General Raštikis met with the commanding general of the Polish I Corps, which had sent a division to the Vilnius territory during the ultimatum crisis. It was he who told Raštikis what the thoughts of the army had been. The Pole envisioned Polish troops entering Lithuania and encountering a major concentration of Lithuanians at the Nemunas River, where combat would ensue. At that point, the Germans would enter Klaipėda and a major war would develop. The Polish general also stated that he had been relieved at the acceptance of the ultimatum.

59 The details of the meeting are taken, for the most part, from Raštikis, I, 515, 519-520.

60 Had the ultimatum included a provision calling for the renunciation of Vilnius as original draft proposals within Polish government circles had contained Kaunas would have found itself in a much more uncomfortable position domestically. Public outcry after the acceptance of the ultimatum placed sufficient pressure upon the government that President Smetona would ask the Tūbelis cabinet to resign. Had the government been forced to formally renounce Vilnius, which had become an object of considerable passion among Lithuanians, political consequences for the Smetona regime may have been much more disastrous.

61 U.S. Legation, Kaunas. Despatch #103 (Diplomatic), March 25,1938, p. 2. See also Žiugžda, pp. 667-669.

62 Lipski, p. 355; U.S. Embassy, Moscow. Despatch #1074, March 26, 1938, p. 5.

63 Jonas Augustaitis, an official of the Lithuanian railroad administration, discusses the Augustavą conference, subsequent conferences, and his contacts with the Poles in general in his Dviejų pasaulėžiūrų varžybos (The Race of Two Worldviews) (Chicago: Author, 1977), pp. 92 ff.; Beck, p. 147; Mačiulis discusses his participation in the Augustavą conference,

pp. 39-41; Norem, p. 198; Royal Institute of International Affairs, p. 93; U.S. Legation,

Kaunas. Despatch #302 (Diplomatic), November 26, 1938, 860M.01 Memel/S34, Enclosure #1, p. 2.

64 Beck, p. 147.

65 See Lozoraitis, p. 252.

66 U.S. Legation, Kaunas. Despatch #103 (Diplomatic), March 25,1938, p. 3.

67 U.S. Legation, Kaunas. Despatch #103 (Diplomatic), March 25, 1938, Enclosure #1, p. 2.

68 U.S. Legation, Kaunas. Despatch #103 (Diplomatic), March 25, 1938, Enclosure #2, p. 1.

69 U.S. Embassy, Warsaw. Despatch #821, November 28, 1938, 760C.60M/457 FP, p. 2; U.S. Legation,

Kaunas. Despatch #485 (Diplomatic), June 13, 1939, 760N.OO/200 G/HC, p. 4.

70 Šliogeris, Antanas Smetona, pp. 161-162.

71 Beck, p. 147.

72 Lozoraitis, pp. 251-252.

73 Raštikis, I, 519, 521.

74 Lietuvos TSR centrinis valstybinis archyvas, f. 383 Lietuvos užsienio reikalų

ministerija, ap. 7, b. 2080, 1. 67 (Central State Archives of the Lithuanian SSR, c. 383 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, f. 7, f. 2080,1. 67), in

Navickas, p. 105.

75 Norman Davies, Cod's Playground: A History of Poland in Two Volumes (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), II (1795 to the present), 431.

76 Raštikis, I, 519 holds an example of this, writing that had Polish-Lithuanian relations been conducted more peacefully, as equals, military cooperation could have occurred during the Second World War, perhaps altering the outcome. Others talk of different scenarios and alliances.