Editor of this issue: Antanas Dundzila

Copyright © 1985 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 31, No.3 - Fall 1985

Editor of this issue: Antanas Dundzila ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1985 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

THE LITHUANIAN FOLK ART INSTITUTE AND RECENT EXHIBITS

VICTORIA MATRANGA

Any family which values its Lithuanian heritage to even the smallest degree generally displays a few examples of native folk art in its home. Visit any Lithuanian home and you'll probably see weavings juostos (sashes) or table-runners amber objects, or a woodcarved figure or wall decoration. Such is the attraction of these items: they are treasured emblems which speak to us of ages and places long gone.

Recognizing this cultural legacy and seeking to continue instruction in the traditional arts, a dedicated group of folk art enthusiasts banded together in 1977 to form the Lithuanian Folk Art Institute. This energetic group has since established chapters in 6 U.S. and Canadian cities. The Institute arranges exhibits, teaches regular classes, conducts workshops and publishes books on folk art. The Chicago Chapter is perhaps the largest, given Chicago's large Lithuanian population, and in recent years, under the clearheaded guidance of Chapter President Aldona Veselka, it has mounted numerous high-quality exhibits that have attracted wide professional and lay audiences. In addition to periodic exhibits in city and suburban locations such as public libraries and schools, the Chicago Chapter produced three major exhibits since 1982, each more beautiful and educational than the last: the first was in September, 1982 at the art gallery Galerija; next at the University of Illinois at Chicago in June, 1983; and then at the Čiurlionis Art Gallery at the Lithuanian Youth Center in February, 1985.

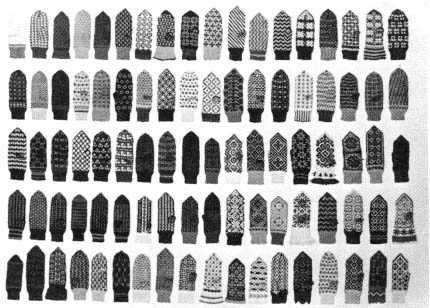

The first exhibit took place at Galerija, a gallery in Chicago's northside gallery district which for three years showcased the work of Lithuanian artists. This exhibit, cosponsored by the Lithuanian American Fine Arts Association and partially funded by the Illinois Arts Council, attracted professional weavers from schools and guilds across the Midwest. Twenty-nine members of the Chicago Chapter displayed their works, weavings wall hangings, traditional costumes, household items, colorful Easter eggs, geometric straw Christmas tree ornaments, ceramics, wood carvings, and knitted articles (90 differently patterned mittens!) supplied by local collectors gave a full view of the folk culture. The contemporary tapestries designed by Aldona Veselka delighted many visitors who did not expect to see the "updating" of traditional motifs. Mrs. Veselka carries traditional weaving techniques and subjects several steps further, and her modern approaches blend the old and the new into a pleasing harmonious synthesis. At the exhibit's opening, she demonstrated weaving on a small loom. Special framing arrangements were devised for the display of regional weaving patterns and this framing system was then reused in subsequent exhibits. Several mannequins dressed in national costumes were a visual treat to the artistically avantgarde neighborhood of Galerija.

A dramatically installed and even more varied assortment of items was collected for the exhibit at the University of Illinois. This exhibit was part of the Second Lithuanian World Festival held in Chicago during the summer of 1983. Thousands of Lithuanian exiles and their descendants from all over the world attended the two-week festival. Many exhibits, sports competitions, political meetings and performances took place on the University campus. The Folk Art exhibit was the most colorful and striking of all the exhibits. This gallery space was in the student union building and was very well suited to the variety of objects displayed. More valuable items, like a unique presentation of amber articles, were included in this exhibit. This exhibit was in place for a very brief time, during a summer interval when University students were not much in evidence, so the audience was primarily the out-of-town Lithuanians in Chicago for the festival, and a smaller number of academic University-related people. The exhibit served an important function, for it highlighted the richness of the folk culture. In the midst of a public urban university setting, it helped us to remember details of the lost rural home-based life. It also provided an educational experience for many visitors of Lithuanian descent, for this was the first time they had seen so many fine examples of their folk art heritage.

The third major exhibit was mounted at the Lithuanian Youth Center to commemorate Lithuania's February 16, 1918 declaration of independence. Each year the Lithuanian community presents special performances, political memorials, and exhibits to recall the happy occasion of independence despite the recent forty years of Soviet domination. The Youth Center houses the handsome Čiurlionis Art Gallery, which serves as a repository and permanent collection of the works of Lithuanian artists and mounts frequent exhibits of current artistic and historic interest. The Folk Art Institute members joyously prepared for this exhibit, feeling very at home in that location, and perhaps for that reason, many more objects were loaned to the exhibit than in the past. Forty-five artists and donors contributed to this exhibit, resulting in the most beautiful and educational event of the series. The textile display was truly dazzling. Not only did the mannequins now proliferate to 8, and include men and children dressed in traditional costumes with dressed dolls completing the overview of costume design, but a great assortment of tablecloths and bedcovers, sashes, wall hangings and tapestries were included. A map describing ethnographic regions of Lithuania visually united the actual woven articles with their function as identifiers of local customs. Household woven cloths like bedcovers were draped on five foot tall columns fanning out the fullness of the intricate designs. Some of these woven items were listed as from a 1920 bridal dowry, for example, adding further historical interest. During the course of the two-week exhibit, one young member of the Institute sat at a spinning wheel, demonstrating the way raw wool was spun into thread for later weaving use. A large floor loom was operated by an older member working a complicated tablecloth design. These "Live displays" were especially appreciated by younger visitors to the exhibit computer generation suburban sophisticates who now have no knowledge of the household crafts once taught by mother to daughter to provide for the basic family needs and to prepare the girl with marriageable skills.

The exhibit included some modern technology to explain ancient techniques; a videotape played several hours of conversation and instruction by Antanas Tamošaitis, veteran folk art historian and craftsman, who together with his wife, weaver Anastazija Tamošaitis, founded the Institute. This particular exhibit was videoteped as well for documentation for the Lithuanian archives and for possible loan to other cities as a fulfillment of the Institute's educational function.

The exhibit included many unique objects fashioned from amber rosaries and other religious articles, boxes, jewelry of all kinds, cigarette holders, and decorative items. Ceramics and holiday specialities such as Christmas tree straw ornaments and colorful Easter eggs were included in the selection. Glass cases sheltered an assortment of old books on folk art, many published during the Independence years and showing the continuity of research and interest in documenting the living folk arts.

Perhaps the most emotional evocative pieces in the exhibit were the wood-carved reliquary statues and waysidde crosses sculpted by Chicago-area sculptor Jurgis Daugvila. These talismans were once typical of the Lithuanian landscape. The pagan past overlaid with staunch Catholicism made each intersection a prayer stop and such precious folk sculptures dotted the countryside before the communist regime eliminated visual reminders of the country's religious heritage.

All three exhibits were scrupulously prepared, well-documented and educational. Identification tags on each object listing province or region of Lithuania, approximate date, media and artist's or donor's name were instructive. Illustrated catalogs printed by the Institute gave more complete information on the objects in the exhibit and descriptions of folk art types: national costumes, ceramics, furniture, textiles, etc., and a brief history of the country and its folk art history. The use of mannequins not only served to appropriately display the costumes, but in a deeper sense, underscored the primary practical function of the costumes as "wearable art." The folk arts enhance our appreciation of the daily environment in a way that "high art" cannot approach. Everyday objects like towel racks and linen chests are worthy of embellishment and are a source of beauty. This is an idea given more credence in the 20th century by architects and designers who consider the total environment, including furniture and household fabrics as an aesthetic mission.

The tradition-bound folk arts allowed for wide individual, albeit anonymous, creativity. The home was the center of production and focus for enjoyment. Simple objects and geometric patterns evolved into complex designs and color combinations, ranging from the muted natural greyish tones of the linen tablecloths to the spectrum in the costumes. As one professional weaver visiting from Ohio observed of the Čiurlionis exhibit's national costumes: "What appear at first glance to be examples of wild and disorganized designs emerge upon closer inspection as rigorously complex arrangements of pattern and color progression."

Folk art by definition means that the artist is unschooled and this art erupts from the inspiration and experience of a nameless craftsman. But now at the Institute, craftsmen receive formal instruction and sign their works. As family traditions have changed, the folk arts have moved away from the hearth and into the classroom. Older artisans, emigrants with direct knowledge of folk sources and traditional methods, find creative inspiration from this past and share the commitment to conservation with the younger members. Middle-aged members, perhaps also emigrants who knew Lithuanian folk art in situ, now have the opportunity to devote time to their studies and work. Younger members, born in the United States, may have never even visited the land of their parents. Their interest in the folk arts springs from different motivations. Some may seek to discover their "roots", others may be expressing a genuine reaction to the high-technology contemporary urban experience and may be reaching for a simpler rural culture. If they were to volunteer to learn old American crafts at a museum facility like the Plymouth Plantation, Williamsburg, or their local historical society, this involvement might not be as personally satisfying or serve as such a direct link to their group past.

From a glance at the roster of Institute members, one can make some observations on the state of the Lithuanian community 40 years from its homeland. Of the younger generation, several are married women with non-Lithuanian surnames; several are active in heritage building conserving activities like folk dancing; a few others are known as artists in modern media. And with the notable exceptions of 3 men ranging in age from 60 to 85 like multi-talented Jurgis Daugvila (weaver and woodcarver), Antanas Poskočiumas (Carver of reliquary crosses), and Kazys Bertašius (weaver of fine sashes), all members are women. This not only reflects the fact that many of the folk arts, particularly weaving, were considered women's work, but that it is women who are most dedicated to the preservation of their cultural heritage. It causes one to speculate on the future of crafts more in the male province of endeavor like woodcarving, furniture making, and metal working, and what is the difference in the composition of the ethnic stock in this country that causes the sensitivity to and appreciation of the folk art traditions to be more inculcated in the females.

Everyone who visited any of the three exhibits here described is surely thankful to the founders and members of the Lithuanian Folk Art Institute for their diligence and commitment. Their work has brought great beauty and new understanding to the modern context of our lives.

Foto Jonas Tamulaitis

Chicago Chapter President and Exhibit Curator Aldona Veselka demonstrates designed weaving technique on a handmade floor loom at the 1985 Čiurlionis Gallery exhibit. In the background are visible weavings by Birutė Arčišauskas.

Foto Algimantas Kezys

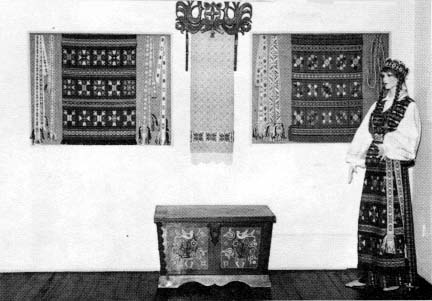

Views from the 1982 Galerija exhibit: Above, weavings by Aldona Veselka, dowry chest by Antanas Tamošaitis and towel rack carved by Jurgis Daugvila. Antique linen towel loaned by the Sisters of St. Casimir Lithuanian Cultural Museum, Chicago. Below: Ninety different examples of patterned mittens knitted by Stasė Tallat-Kelpša.

Foto Algimantas Kezys

Foto Jonas Tamulaitis

View of 1983 exhibit at the University of Illinois at Chicago A. Montgomery Ward Gallery. From left, mannequin wears Kapsai region costume woven by Aldona Veselka, center mannequin dressed in Aukštaitija region attire; right model displays Lithuania minor costume woven by Anastazija Tamošaitis.

Foto Jonas Tamulaitis

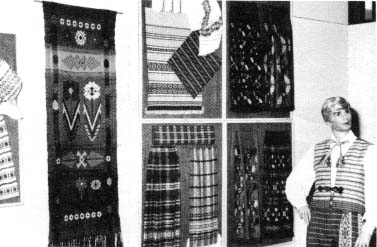

A view of weavings from the University of Illinois exhibit. From left wallhanging "Garden" woven by Daina Kojelis. Arrangements of weavings on the four panels display weavings by (top left) Gražina Urbonas, (bottom left) Aldona Underis, (right) Aldona Veselka. Mannequin dressed in Zanavykija costume woven by Anastazija Tamošaitis.

Foto Irena Markvaldas

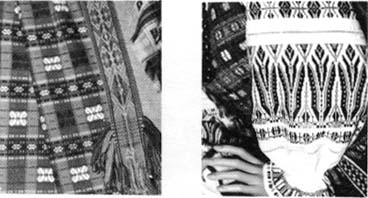

Left designed weaving and sash of Dzūkija region by Aldona Veselka; right Woman's blouse sleeve Zanavykija region also by Aldona Veselka. Vest woven by Vida Rimas.

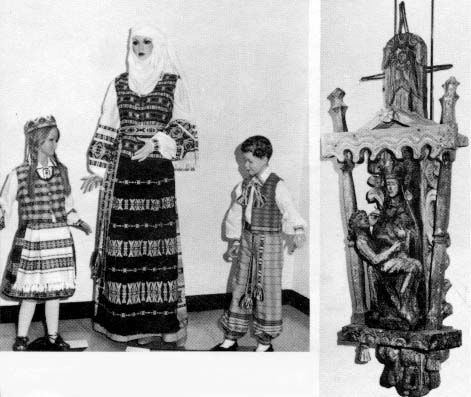

Top left photograph shows a mannequin family dressed in costumes of the Aukštaitija region. Little girl's costume woven by Dalia Varanka, woman's costume by Aldona Veselka and young boy's costume by Lydia Liepinaitis.

At right: Chapel wood sculpture, Pieta, carved by Jurgis Daugvila. Artist Jurgis Daugvila practices the traditional folk art techniques in his expressive renditions of religious and folkart subjects.

Chapter member Dalia Varanka working at the spinning wheel at the Čiurlionis Gallery.

Foto Jonas Tamulaitis

Foto Jonas Tamulaitis

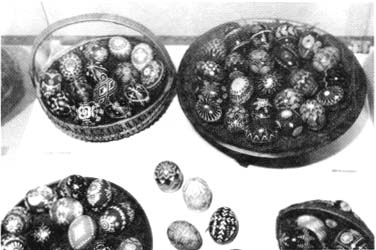

Top photograph shows aprons and sash in the Zanavykija patterns woven by Aldona Veselka. Lower photograph displays an assortment of handcolored Easter eggs done in the scratch technique by Paulina Vaitaitis, Marija Gotceitas, Liuda Butikas and Marija Krauchunas and wax technique by Rūta Daukus (right top basket).

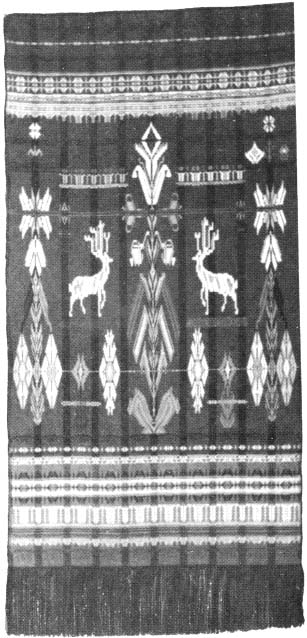

"Forest Friends," handwoven wallhanging created by Aldona Veselka. Wool on cotton, 25.5" x 48.5", 1982.

Foto Jonas Tamulaitis

Members of the Lithuanian Folk Art Institute's Chicago Chapter weaving studio at the Čiurlionis Gallery exhibit's opening night, February 15, 1985.