Editor of this issue: Antanas Dundzila

Copyright © 1986 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 32, No. 4 - Winter 1986

Editor of this issue: Antanas Dundzila ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1986 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

CHEMISTRY GOES TO POT

SILVIA KUČĖNAS-FOTI

"If the temperature isn't high enough, the chemical process is frustrated/' says Marytė Gaižutis, chemistry professor at Moraine Valley Community College in Palos Hills, III. "The magnesium oxide, the sodium, the lithium, the lead must be precisely weighed. I follow the 'recipe' from this book, but it doesn't always work out. Maybe the elements aren't pure enough. The bonding process isn't always realized"

She is referring to the preparation of glazes for the ceramic pieces she creates in the basement of her home in Marquette Park, Chicago. This basement is her studio, filled with clay, shelves of bottles with MO2, CO2, or Z written on them. Her kiln is next to the washer and dryer, her potter's wheel is at the other end of the basement, near the shelves of finished and unfinished ceramics pots, plaques, vases, candleholders, plates.

Holding a Ph.D. in chemistry from the Illinois Institute of Technology, Gaižutis was once a research assistant in the renal division of Michael Reese Hospital and a research associate at the department of endocrinology at Cook County Hospital of Chicago. Today she is working on ceramic pieces for her next art exhibit to be held in New York this spring.

Apparently Gaižutis is carrying on a long tradition of combining chemistry skills with ceramics. The chemist's attraction to ceramics can be traced back to 1709 when a young alchemist, Johann F. Bottger in Saxony stumbled upon the elements of true Chinese porcelain. Ever since then, ceramics has been intimately linked with chemistry.

Ceramics is an art, but it also demands scientific precision. While Gaižutis methodically weighs and combines chemicals in various proportions in order to create a specific glaze color, one soon thinks of her studio as a laboratory.

"Barium is for blue, iron gives brown, cooper gives green, cobalt gives a deep blue," she explains. "I'm happy with my black, but sometimes it turns green. I still can't figure out why. One packet of chemicals is never the same as the next one you buy. So the proportions constantly change."

She talks about her struggles in trying to translate her inspiration into a final product. Like any artist, Gaižutis often encounters frustrations in adapting her spirit to matter. The properties of the physical matter are never exactly the same, so she continues to conflict with the chemical elements until she finds a close approximation of what she wants.

"You have to make lots and lots of combinations. Sometimes you never get what you want. Look at this bowl. When I was experimenting with the glaze on a sample it worked fine. But after I fired the bowl, the glaze just pinched together. It drooled off. It just wasn't chemically compatible with this clay," she sighs.

Despite her personal disappointments with chemical imperfections, her work is gaining a wider audience. In the past 16 years, Gaižutis must have created at least 1,000 pieces. She has been teaching ceramics at Balzekas Museum in Chicago since 1977. She has shown and sold her art in Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Baltimore, Beverly Shores, Washington, D.C., New York. Two of her pieces were recently purchased by the State of Illinois Building in Chicago.

Of her 1977 exhibit in Chicago, a critic wrote in Draugas, "She is no longer a debutante, but a strong artist. Each plate is different, having an individual hidden meaning. Let's look at this plate, 'In the beginning.' We see the chaos of creation, the earth to be as a fired ball and a silhouette of man with woman."

In the early part of her career as a ceramicist, Gaižutis stayed away from decorative pieces. "At first I thought I should make functional pieces. There was a rebirth to nature, of using hand-made things. But that trend fizzled out. And financially, people just don't buy these things anymore. Now I try to make things from a more personal angle and I'm going toward the non-functional. Yet I still have a conflict between the functional and non-functional."

She is also trying to adapt her ethnic background to her art. Gaižutis was born in Kaunas and came to the United States as a child. To Gaižutis, her ceramic pieces should be an expression of her native land. Here too, she is faced with trying to combine the proportions of yet another element the Lithuanian one.

"Somehow, I can't finish searching for a way to make my work look more ethnic, more Lithuanian. Maybe it's personally important to me. I can't seem to create something that is completely me."

Perhaps it is this expressive yearning which constantly drives her to her studio. This searching energy compulses her to create a ceramic piece that is 100 percent her.

In the spring of 1985, Gaižutis began experimenting with woven Lithuanian cloths. She pressed a woven cloth on wet clay, hoping the impression of the cloth's design could be transferred to the piece.

She pulls out a bent plaque, which has a traditional Lithuanian design impressed upon it. Its sides are Albany brown, descending into a sea green, leaving white with the design on the bottom.

"These presses are turning into a vehicle for my ethnic realization, but I still haven't found a satisfactory way to show my heritage in these ceramics."

Maybe if she was satisfied, she'd stop working, she says It seems her background in science pushes her to exactness yet art is never precise.

Ultimately she is faced with herself, the Marytė Gaižutis element, the most difficult element to control. She hesitates to use the word "grow" because it is too presumptuous of choice which implies improvement. Instead, she says her "me" is always taking on different characteristics. Even a she works on one piece, her "me" is in a state of flux.

This changing element within herself, however, is exactl what enchants viewers when they see her pieces. They can feel her intensity, the energy of her calculating scientific mind struggling to create a personal piece an artistic, yet precise expression of herself. If she ever found a way to express herself 100 percent, with all the exact proportions o the chemical elements, the Lithuanian element and the Marytė Gaižutis element, she probably would, as she admits, stop working.

But until this occurs, one still has an opportunity to observe a piece Gaižutis created while trying to harness herself, her clay and her chemicals. Her spiritual struggle with matter will continue to draw excited viewers who are eager to see how much closer her art has come to expressing herself.

Western impressions, 5 feet,, 1984

Soft Image Seeking, 6 feet, 1986, Chicago

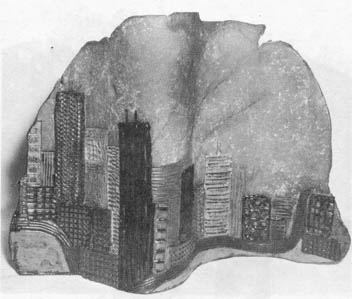

Chicago scene, 15 inch high, 20 inches wide, 1983

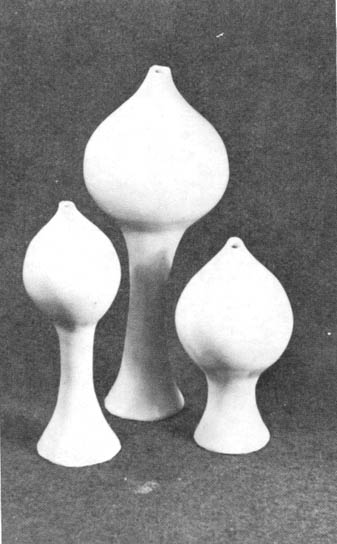

Porcelain, 12 inches, 1982

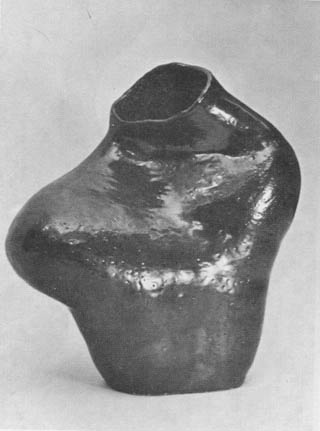

Composition I, 19 inches, 1983

Pre-kalnų upelis, 20 inches, 1983

Mountain brook series I, 20 inches, 1986