Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

Copyright © 1988 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 34, No. 1 - Spring 1988

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1988 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

THE TWO SIDES OF PRANAS GAILIUS*

VICTORIA MATRANGA

Imagine a faun dancing in a mythical forest and you have a vision of the dynamic Parisian Pranas Gailius explaining his artworks hung on the walls surrounding him. In the fall of 1987, Gailius was in Chicago for two simultaneous exhibits, one at the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture and another at the Alliance Française. The exhibit at the Alliance Française consisted primarily of artists' books of French poetry and other works presenting his French perspective. Gailius left Lithuania when he was a teenager and has lived in France since 1945. He is a well-known artist in both Lithuanian and French milieux. Gailius' expansive energy filled the room as he discoursed on his themes and techniques, gesticulating grandly and peppering his rapid-fire Lithuanian speech with French exclamations and expressions. "I am always an artist, whether I am writing or reading," he says, and in the Balzekas Museum exhibit, he revealed his dual nature in a display of artworks disclosing his intimate dichotomies.

The exhibit included 19 examples of individual graphics, three of which were single page interpretations of poems written by three different poets; a series of paintings numbered 1 through 10 entitled Sielrankšluoščiai, and an artist's book of 12 plates, Donelaičio pamokslas per sukaktuvių Mišią Donelaitis' Sermon at his Anniversary Mass, Second Lithuanian Suite. This Suite is a remarkable document whose significance is amplified by the juxtaposition of the painting series shown concurrently.

As Gailius puts it, the Second Lithuanian Suite is the second half of his exposition of the "profane et sacré" aspects of his Lithuanian experience. The first, secular, work was the 1968 series based on the collection of Lithuanian folk songs loosely translated into French by O.V. Milosz. This second, religious, suite is a representation of the fusion of paganism and Christianity in his Lithuanian sensibility. For him, the folk culture is manifested by the physical reality of folk art the rough wooden carved crosses and rūpintojėliai (sorrowing Christ sculptures) overlaid with the mysticism and then the aural and visual refinements of Christian art. "In my hometown of Mažeikiai, the church was the closest thing we had to an art museum. The church served as a gallery for painting and sculpture and a concert hall. I sat in the pews listening to the chanting during the Mass and other rituals and examined the prayer books. The prayer books were the embodiment of the word. The graphic power of the marks on the page were embossed on my memory."

The Second Lithuanian Suite occupied Gailius for three years, from 1983-86. The 40 copy edition consists of 10 numbered pages measuring 22" x, 15", a cover and dedication page. He dedicated the work to the memory of Rev. J. Krivickas, a priest who befriended him soon after his arrival in Strasbourg in 1945. The dedication also credits his patrons, A. Rimkus and Dr. R. Nemickas, who supplied financial support to the project.

The Suite depicts the middle section of a three-part poem, "Poetas Kunigas" (The Poet Priest), by Kazys Bradūnas. The poem is a triptych commemorating the 200th anniversary of the death of Kristijonas Donelaitis, an 18th century minister whose poem Metai (Years) is one of the canons of Lithuanian classic literature. In Bradūnas' poem, Donelaitis emerges from his grave to visit his former parish in Lithuania Minor, where 200 years after his death, he finds little remaining of his countrymen who once farmed there and attended Mass (Mišios) in his church. In the central portion of the poem, Donelaitis ascends the pulpit and preaches to the assembled congregation. The poem is unusual in the way all three sections suggest the importance of the word and its physical impression, which could have inspired Gailius' conception. For example, in the beginning segment: "Dėkim žodj tartum Dievo pirštą/Prie širdies, prie atviros žaizdos" (Let us place the word, as if it were God's finger/to our heart, to an open wound), in the third segment: "J darbus bėga žmonės/Jų pėdos driekiasi per baltą knygos popierių") The people run to their chores/Their footprints tracking across the book's white paper). In the central section, Bradūnas reworks the first line of Donelaitis' poem, remembered by every Lithuanian student: "Kai saulelė vėl atkopdama budino svietą/Tai tiktai raidės remdamies atsikėlėm" (And when the rising sun wakened the earth/We arose with only the words to support us). So, Bradūnas implies that the strength of words resurrects man and nation.

Gailius explores the interaction of literal and visual elements. He records what he reads, shows us how he sees, and redefines the nature of language itself. International contemporary art often contains a verbal message. It is not uncommon for artists to incorporate text into painting or graphic work. Frequently, however, the verbal message is the primary message. The word as concept, or the word in service to political and/or social commentary, is the aim. In the Second Lithuanian Suite, Gailius' visual declamation forces the viewer to unravel many layers in the meaning of words. A poet's art is perceived visually or aurally. The poet is in direct control of his work when he himself recites it or when he designates how the words will appear on the printed page. A performer reciting or singing a poem intensifies the ephemeral nature of the poem's sound with his inflections. Gailius understands the word to be a unit of human communication. The words carry their own visual power and function as elicitors of imagination. To the customary two senses, Gailius adds a third (and perhaps a fourth) dimension to the apprehension of poetry. His words are sculpted. The high relief pressed into heavy weight paper depends on lighting to a dramatic degree for its impact. Physically experiencing this poem by removing each stiff sheet from its clear plexiglass box and holding each page while reading transfers the object from Gailius' hand to ours, not unlike the passing of bread during a religious or social ritual. This physical involvement imparts an atmosphere of reverence and a measurement of time as in the recitation of a prayer or the division between scenes of a performance.

A poet himself, Gailius also absorbs the poetry he reads. He says, "I am carried on the wave of the poem." His congruence with the emotion of the poem is conveyed by the totality of the marks and the cumulative effect of the words. In the Second Lithuanian Suite, he attempts to portray the mood, sounds and colors of a Sunday morning in a country church during the liturgy of the Mass. Here the words are the architecture of the page, as the Word is the foundation of the Christian faith. Words, in the chanting and recitation of the Latin Mass, form the border and background of the experience. Words and letters scattered about the page become actors filling the space around the kneeling human figures. The words of the frame are almost unintelligible, and in some instances, easily replaced by vegetative motifs in the visual structure, akin to ivy climbing the church walls. The words envelope the huddled mendicants and resonate like antiphonal prayers. The fugue and counterpoint of words emerge from the page in size, color and height rendition, joining the people and their words in choral harmony. The play of light and shadow in the relief evoke the interior of the church in which this drama occurs.

Perhaps Gailius is so drawn to the use of poetry in his art because he is the product of two cultures, each of which reveres its language. Born in 1928, Gailius left Lithuania during World War II and settled in France. By the age of 17, he was studying art in Strasbourg. After studying painting in Paris with Ferdinand Léger, he studied lithography at the Ècole des Beaux Arts. As he matured, the subtlety of his French education blended with his Lithuanian country experiences. Syncretism of urban and rural, Christian and pagan, reason and passion developed. In the Lithuanian emigrant diaspora and in the native country, the language is a symbol of physical and cultural survival. In France poets have been cultural icons for centuries. The purity and use of his language is an emblem of the Frenchman's manhood and sophistication. Either end of the spectrum is foreign to the video culture of America.

The fact that Gailius "illustrates" poetry in both languages indicates to some extent that he has internalized them equally. French and Lithuanian are almost interchangeable for him, as evidenced by two pieces in the Balzekas Museum exhibit. A Lithuanian poem by Eglė Juodvalkis and a poem in French by A. Mickevičius present basically the same visual composition and coloring.

Gailius continues a long tradition of book illustration in both cultures. All major Lithuanian graphic artists have illustrated books. V.K. Jonynas' classic 1940 engravings for Donelaitis's "Metai" comes to first to mine. Telesforas Valius, Vaclovas Ratas, Gailius' fellow Parisian Žibuntas Mikšys, Romas Viesulas, Paulius Augius, Viktoras Petravičius have all matched talents with poetry in scores of books. In Augius' Žalčio pasaka and Petravičius's G/esmė apie Gediminą, the artist's calligraphy is integral to the textual interpretation and design of the page. In the French tradition, many artists including Picasso and Matisse sought a unity of expression with poetry. Baudelaire, Mallarmė and other late 19th and 20th century poets experimented with the identification of sensory stimuli and attempted to combine sounds, colors and scents. Gailius has carried this art to its natural conclusion in the alliance of sequential text, color, line and sculptural elements.

Gailius speaks frequently of the "inner inevitability" and "spontaneous correctness" of a composition and the internal requirements of a piece. It is as if he is revealing, as did Michaelangelo, the figure encased in a block of marble; or releasing the melody trapped in a keyboard. When he speaks of how he "feels" his graphic process, Gailius demonstrates by thrusting his hands in the air as if he were kneading dough or clay. "The two hands raise the relief to lift it with my hands is to have the depths and contours of the relief intimately connected with my being. I pull all of my own work. I am physically carving the lines and shapes (whether in copper, wood or linoleum), manipulating the presses, working the wet paper. Once the impression is made, there is no going back, no correction. The artist cannot seek direction in the technique; the technique is silent to his questions. The force of the will, the vision, is in the hands. The material merely gives form to what is in the hands. Another person, motivated in a different way, would not extract the same result from the medium."

But Gailius also states that "at the base, I am a painter. Everything else comes through that." He acknowledges his teacher, Ferdinand Léger, with whom he studied during 1950-52, as the one who taught him how to look. "I am still under his influence. He was one of the few artists at that time, along with Matisse, who knew who he was, knew what he was doing, and knew how to transmit his knowledge plastically and verbally. Léger gave me the glue that keeps all my work together." For several years, Gailius also studied with a Japanese calligrapher. This oriental influence is inferred by the condensed design and distilled quality of line and form in the Bradūnas pages. The spareness of his elegant compositions is most visible in the single graphics works on display at the Balzekas Museum exhibit. In these works, the velvet tones of the blacks and the clear, almost watercolor "fragrant" colors in his "Gegužinė" (Spring Outing) series reflect the discipline within the easily flowing lines of the strokes.

When speaking of his paintings, in the manner so typical of the way Gailius has resolved his Lithuanian and French traits, he says, "The act of painting is direct. There are no intermediaries as with the print. Here, no involvement with board or stone, paper or press. In a single step, I have form. Spontaneously, the paganism erupts. I can embrace the painting with one motion." As we see in the Sielrankšluoščiai series of paintings, the cultural superimposition of Christianity is stripped away, baring the rough-hewn folk art essence.

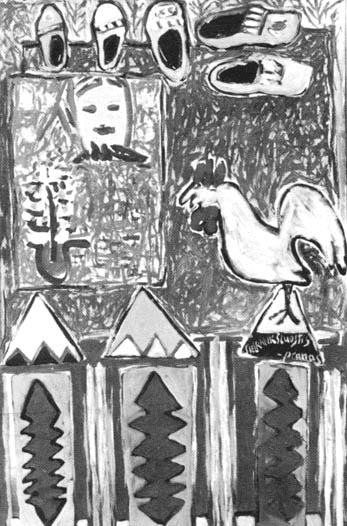

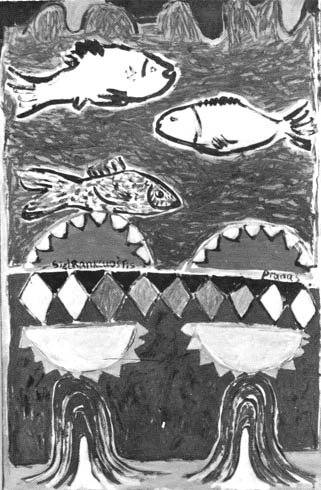

Some visitors to the Balzekas Museum exhibit thought that Gailius could have devised the word as "Sielšluoščiai." He vigorously disagrees. The rank(a) (hand) must remain in the composite word, he says, in order to completely allow for the many allusions. The association of the siel (soul), rank (hand) and šluoštis (wipe) were critical to his suggestion of the hand's relation to the soul. The imagery of what hands do wiping, rubbing, caressing, embracing, worrying and the levels of the metaphor (washing one's hands of something, the biblical Veronica receiving the image of Christ's face on her towel) are then set in motion. The paintings' zoned compositions including horses, birds, fish, stars, flowers, candles, wooden shoes, folk dancers, fishermen and bescarved peasant women are a tumble of memories from his Lithuanian boyhood. Bright colors, frequent use of green and red, thick lines and angular shapes recall the primitive wooden folk art objects that decorated homes and appeared in the landscape. As the Second Lithuanian Suite is as carefully measured as a procession, the Sielrankšluoščiai are bold, impulsive and intense. Gailius retains vivid reminiscences of his youth's rustic simplicity. He remembers the effects of sunlight on the fields, the feeling of the wooden figures he carved while tending grazing cows, and the sight of deep frozen ruts dug by carriage wheels in the mud. In this series of paintings, glimpses of such recollections appear disjointedly as if in a dream.

Gailius' first exhibit was in Paris in 1955. The puzzled organizer of the exhibit could not identify which of the names Pranas Gailius was the surname and chose Pranas. From that time on, the artist has been known professionally by this single name. He exhibits regularly in Parisian galleries, the Bibliothèque Nationale and the Beaubourg Centre Pompidou; in other French cities, throughout Europe, the U.S. and Canada. He says that French art critics are intrigued by the cognitive dissonance of his Lithuanian sympathies within the French school.

Since his first trip to the U.S. in 1963, he has been a frequent visitor to Chicago. During his latest sojourn, he mused about the communicative function of his art, "We can only hope that we will become clearer in the eyes of others." From his most recent Chicago exhibit, we can see more clearly how deftly he has integrated his means of artistic expression and his own "internal inevitabilities." With the pairing of two seemingly disparate entities, the book and the paintings, Gailius reveals that his inventiveness flows like a river between two topographically distinct banks. The lasting impressions of his boyhood along the Venta and his adult perceptions beside the Seine converge into the stream of his creativity.

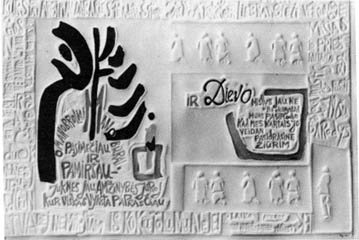

"Donelaitis' Sermon at his Anniversary Mass" page 6, 1983-1986,

embossed paper 15"x22". Lyrics by Kazys Bradūnas

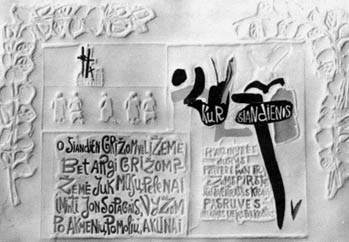

"Donelaitis' Sermon at his Anniversary Mass" page 7, 1983-1986,

embossed paper 15"x22". Lyrics by Kazys Bradūnas

"Sielrankšluostis I" oil on canvas 48x32 7/2" 1987

"Sielrankšluostis II" oil on canvas 48"x32 1/2" 1987

"Sielrankšluostis III" oil on canvas 48"x32 1/2" 1987

"Sielrankšluostis IX" oil on canvas 48"x32 1/2" 1987

* This article discusses art works that were displayed Sept. 25 to Oct. 17, 1987 at Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture, 6500 S. Pulaski Rd., Chicago, III.