Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas

Copyright © 1988 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 34, No. 4 - Winter 1988

Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1988 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

LITHUANIAN ART IN AMERICA

ALGIMANTAS KEZYS

Can Lithuanian art in America be defined? Attempts have been made but a consensus is hard to reach on just what constitutes ethnic or Lithuanian, as in our case art. For the sake of discussion, one can probably say that ethnicity in art is that element in the creative process of an individual or group which shows the influence of past traditions. There is no such thing as Lithuanian art in America, if one expects to find some kind of identifiable, common Lithuanian style. But there is such a thing, if one grants that the cultural and social experience of Lithuanian-Americans, their history, memories and imagery differ to some degree from Americans of other ethnic backgrounds.

Lithuania as a nation has a long history dating back to the twelfth century. The traditions of its artistic endeavors are also deeply rooted in its people. The "authentic" elements in this tradition are considered to be those which have originated with the practitioners of folk art. Those intuitive artists were "unspoiled" by exposure to foreign influences or higher education but relied for their inspiration on natural talent and belief systems.

In compiling this survey of artists of Lithuanian descent living in America, I found that many of them still possess a definite connection with their ancestral background. Often they are influenced by its traditions and boldly incorporate its best elements into their universal art. Some of them have achieved recognition just because they have adopted a method, a subject matter, or a feeling for color and composition which is uniquely theirs as ethnics. This, of course, does not diminish the stature of others who work well outside their ethnic dimensions. Ethnicity is not a must for artistic expression, but where it is an important element, it is interesting to discover what it is and how it works.

In this portfolio, an attempt is made to present the latest work and statements of Lithuanian artists living outside their homeland (especially in America) who manifest ethnic tendencies in their art; to uncover some of the undercurrents of their creativity and pinpoint the influences of their ethnic background.

Jurgis Daugvila represents primitive Lithuanian wood-sculpting which emulates authentic folk masters of an earlier age. A student in the Lithuanian refugee school of art in post-war Germany, Ecole des Arts et Metiers, in Freiburg, Daugvila first specialized in tapestry weaving, then went through a phase of creative stained-glass windows in plastic, and later was a stage decorator. Now he works exclusively recreating wood sculptures of anonymous Lithuanian folk artists of the last century. His are the hands and the soul that went through the routine of formal training in art, and after he became an acknowledged artist in his community, he decided to "unlearn," retracing his steps back to the basic and primitive art forms. He now lives in a wooded area in Beverly Shores, Ind., near Lake Michigan, and sculpts his "Rūpintojėliai" and 'Pietas" as if the twentieth century has not yet arrived. Curious visitors have joined his clientele, and he is nor able to meet the demand for his wooden sculptures. Apparently he has struck a cord in the population which still remembers old traditions. His art appeals to both the informed, as well as the uninitiated. He is recreating a tradition that is not artificially imposed but is felt and lived by thousands of his fellow countrymen. Not too many of such sculptors are left in the world, including the confines of the mother country, Lithuania. Wherever they appear, their work is sought after and treasured, both as a relic of the past and as a work of art that has universal appeal. Daugvila has come very close to the source from which the distinctness of art called Lithuanian has emanated.

Viktoras Petravičius is the predecessor and "grandfather" of a whole generation of younger Lithuanian graphic artists who take folk art as their leading motif. Petravičius elevated the primitive Lithuanian woodcut to an international level by winning the Grand Prix in the Paris International exposition in 1937 for his "Gulbė, karaliaus pati" (Swan, the Wife of the King). He himself continued working in the same tradition all his life, gaining respect and admiration for his black-and-white and hand-colored oil graphics, which have a distinct although elusive Lithuanian character. Not only his images of old Lithuanian fairy tales of contemporary village life are marked with clear ethnic nuances, but also his monumental works about exotic gods and goddesses in ancient woods or castles have an atmosphere that every Lithuanian is able to identify as his own. In his art, pagan as well as Christian symbols are combined into a pantheistic religion, which many Lithuanians still feel pulsing in their veins. This is the imagery that Petravičius creates by weaving ethnic elements into universal issues such as birth, death, afterlife, man's inhumanity to man/and above all, man's kinship with the earth and fellow living beings.

Magdalena Stankūnas, a student of Viktoras Petravičius, has been doing oils and hand-colored woodcuts about distinct Lithuanian subjects "Women at Work on a Lithuanian Farm," "The Months in my Homeland," "The Legend of Jūratė and Kastytis" for many years. Her most recent series concerns the goddesses of Lithuanian mythology with the exotic names of Lazdona, Aušrinė, Madeina, Laima. They represent "Deivės" or goddesses of the ancient pantheistic belief system. In dealing with this subject Stankūnas fulfills the role of a Lithuanian prophetess trying to revive ancient values which are all but lost to the new generation. She also stays in touch with the subconscious and the supernatural, striving to elevate art and humanity to a higher spiritual plane. But the source of her inspiration is mundane memories of a happy childhood spent in her homeland amid tales, customary family rites, and legends. Her works are private, loving meditations and sweet remembrances of the folklore which told of the goodness of hard work, the love of the land, the mystery of the cosmic spirits, and the wisdom of our ancient gods.

Veronika Švabas is a student of Viktoras Petravičius. She works in woodcuts, then handcolors her black and white prints. Švabas has been classified as primitive. Her technique and subject matter are both attractive and heartwarming. She states that she likes classical music in which she somehow overhears the tunes of Lithuanian folk dances. Thus inspired, she produced a series of hand-colored woodcuts about popular Lithuanian folk dances: Sadutė, Blezdingėlė, Malūnas, Suktinis, and Kubilas.

Antanas and Anastazija Tamošaitis, a husband and wife team, have both spent a lifetime researching and exploring the roots of Lithuanian authentic art forms. They have scrupulously incorporated their findings in their own art, such as weavings of Lithuanian national costumes, decorative Easter eggs, sashes, paintings, and tapestries. The direction of their personal art is, as expected, marked by the predilection for treasures found in folk art. Even their abstract art shows the unmistakable influence of folk traditions in their choice of colors, subject matter and design. Their statements about their most recent work stress the tendency toward universality, especially when they speak about their interest in cosmic panoramas or skies, moons, and planets. In Antanas Tamošaitis' oil painting "Erdvės vingiai" (Criss-crossing in the Cosmos) he visualizes the rhythmic patterns found in creation, "the comings and goings of the stars and the traveling of our Sun, which sometimes appears bright, sometimes sad and pale; but its path through the skies is always uniform; the Moon changes its shape and mood as it moves through the night amid patterns of stars." Nevertheless, the artist looks at these wonders through the frosted glass of his old country cottage. His oil paintings recall the pattern created by frost on a window. It gives him an infinite variety of geometric zig-zags on the plane of the canvas to create shapes, moods, and themes. Anastazija Tamošaitis also speaks of the universe and its observable wonders in her painting "Mėnulio prošvaistės" (Glimmers of the Moon). Her moon "shines through the mysterious branches of the forest, changing substances into shadows, shapes into fairy tales, trees into beings." But the mystery of the night appears mixed with colors and motion as if it were a close-up of an old-fashioned Lithuanian skirt on a dancer dancing in the moonlight. It is apparent that the picture was created by the same hand and the same heart that did the earlier wall hanging "Eglė, žalčių karalienė," which refers to the popular Lithuanian fairy tale "Eglė, the Queen of the Serpents," or "Sekminės" (Pentecost), the playful tapestry dotted with young girls dressed in authentic Lithuanian costumes during the feast of Spring.

Vytautas Ignas. Both in his paintings and lino cuts Ignas presents contemporary expression of an ancient iconogra-phic style. He follows very closely the original forms of Lithuanian folk art, but his individuality is so apparent that no one familiar with any of his work can fail to identify his unique style. The imagery is Lithuanian mythology or contemporary Lithuanian scenery surrounded by hosts of typically Lithuanian ornaments and decorations. Ignas developed this personalized approach to antiquated subjects early in his career and has maintained it unchanged ever since.

Ada Sutkus works in fiber. She admits she is a feminist working in a medium which historically was associated with women's interests tapestry, weaving, embroidery, etc. Fiber art technique, as Sutkus practices it, is primarily "wrapping," where a thread or raw fiber is wrapped around a string of jute, nylon, or raw acrylic fiber. This "fortified" or "enriched" rope is either attached to the canvas, left hanging loose, or manipulated in a variety of ways to achieve a three-dimensional effect. The whole process of creating a finished piece is very slow, comparable to gobelin weaving, but it offers new possibilities, especially in three-dimensional treatment of the composition. In an earlier monumental work, "The Tree of Souls," Sutkus demonstrated her elegant style, but also betrayed her mystical inclinations, verging on the pantheistic tendencies of the Lithuanian past. Her recent works "S.O.S." and "Peace Conference" show what she can do with color in fiber art. These two wall hangings are also social and political statements. The author has strong feelings about peace in the world. "We can create a world without war" is the message of "Peace Conference". "S.O.S." is a tribute to the saviours of her family during the war the horses who pulled their wagon through the perils of World War II to safety in the West. The memory of this experience has lingered in her mind for more than forty years, and only now was she able (having completed her maternal duties at home) to realize those pent-up emotions by producing this piece in gratitude to those heroic horses. Sutkus delves into the remembered past, notably to the happy plus unhappy experiences of her childhood, for inspiration and ideas.

Zita Sodeika produces two kinds of art work paintings and drawings. These represent two different techniques and also two points of view. In her drawings she gives her comment, direct and unambiguous, about our human situation. Here she is philosophical, satirical, and offers psychological insights. In her paintings, which are abstract and surrealist, Sodeika stresses pure composition and intuition which rely both in content and style on her inner state of mind and the subconscious. She says that in her paintings nothing is preconceived. "I have no ideas in advance," she says. Sodeika starts with an empty canvas and a mind swirling with ideas, and then allows her sense of form and color to guide her brush. The finished art is a product of her imagination, reflecting the imagery that was somehow implanted in her mind by some mysterious experience known to her alone. But when a series of these surrealist abstractions was completed, Sodeika realized she recognized a meaning in these pictures that startled even her. She thinks the meaning is authentic. It probably lay dormant in her subconscious all these years and only at the end did the artist herself suddenly realize what she had created. She said these compositions have a very personal significance, traceable back to her childhood, part of which she spent in her hometown in pre-war Lithuania. This part of her childhood was peaceful and carefree, but then the war came and family was forced to leave the places she so loved. The scars that were produced by this separation have never really healed. Sodeika admits that she continued having nightmares about this displacement for more than twenty years after the war. So this is what, in her opinion, these creations mean separation, displacement, disembodiment. The figures and the forms in the pictures float in the air; nothing seems attached to anything solid and permanent; a lonely sheet of paper flies in space without having a permanent home or abode. The hidden meaning of these abstractions suddenly becomes clear Sodeika has painted her autobiography, which is about being homesick, abandoned, a perpetual stranger in the world. She speaks here with authority for her own generation of children of war, now fully grown but still bearing the wounds inflicted upon them by the cruelty of war, separation, and death.

Elena Gaputytė's current work consists of installations-performances, for which she has been labeled a "Peace" or "Anti-war" artist. She has spoken with many World War II witnesses, and she herself experienced that war. For the last ten years her work has been closely connected with wartime memories. She works either to honor the memory of the deceased or to memorialize those who survived and struggled on as widows, orphans, invalids, and displaced persons. World War II brutally wounded her parents, enslaved her own country, Lithuania, and warped the spirit and the face of Europe. Cities became smoldering ruins, villages and orchards were reduced to ashes. These experiences, continuously scrutinized by her mind and shaped by her hands, are the basis of Gaputytė's art today. She works with time based elements, such as live lights, whose flickering flames and dignified atmosphere form the core of the performance. "I believe very strongly, Gaputytė says, "That today, as never before in human history, every one of us could influence and promote Good and Evil effectively on a global scale. This conviction initiated my search for the most suitable art form which would clearly and loudly expose the price Europe has paid in human lives and unbelievable suffering during two World wars. I see my work (installations, performances, videos) as a personal commitment through my art, to remind everyone, especially the young today, not only of the approximate figures of war dead 25 million in the First World war, 56 million in the Second World war but also those unbelievable circum-stances and conditions in which these victims perished. I see my works as a moral commitment. I refuse to believe in a horrendous ending of our world. I wish to use my work as a deterrent against a new war."

Jūratė Bigelis Silverman's technical approach involves the exploration of the relationships between print and paper. She is fascinated by how the imagery, texture, and color of each are mutually reinforcing. She first prints on handmade paper, plain or with imagery suggested by the papermaking process. Then she proceeds to imbed the work into a larger handmade paper assemblage, either altering the print by segmenting it, compacting it, folding it, or using it in its entirety. Involvement in the papermaking process gives her a historical sensitivity and awareness that transcends the action and orients her to a broader historical perspective in her imagery. Her imagery then arises out of this state of mind. In less abstract work she focuses on her family's past, incorporating it into etchings. Such is the subject matter of the series of etchings titled "Origins." There are three levels of symbolism in this series: 1) Her personal origins, particularly through her mother and her grandmother. "All my knowledge of Lithuanian culture, history, literature, art comes to me from my mother and therefore from my grandmother. My grandmother, as part of the maternal line, represents a direct link with my heritage. This influence has been a formative one and feeds directly into my imagery." 2) The origins of the handmade paper, in that the pieces of the rag used to make the paper are imbedded in the actual paper to create an abstract design. 3) Broader symbolic meaning reflecting man's origins. Bigelis explains: "The abstract design created by the imbedded rag depicts aspects of man's development in history."

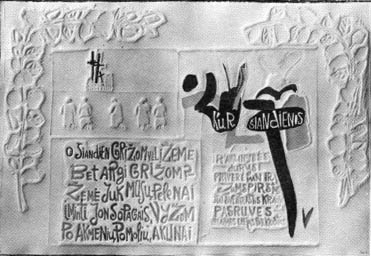

Pranas Gailius, formerly a poet, now a painter and graphic artist, in his recent opus gives visual interpretation of Bradūnas' poem "Donelaičio pamokslas per sukaktuvių Mišią" (Donelaitis' Sermon at His Anniversary Mass). The setting is 18th century Lithuania Minor; a Lithuanian Protestant pastor preaches to his congregation at his anniversary Mass. The language of the poem is antique, but it still rings true. Pranas falls in love with it and immortalizes it in his "Second Lithuanian Suite." Here the verbal message constitutes the entire graphic individual letters, syllables, words, free-flowing lines dance on the embossed sheet in endless variety. Pranas' latest series of oil paintings, called "Sielrankšluoščiai" (a word of his own coinage meaning "Hand Towels of the Soul") is also typically ethnic. They are visual representations of experiences and memories from his Lithuanian boyhood.

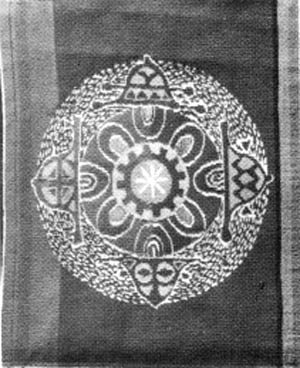

į Vanda Balukas had her formal art training in Vilnius, Lithuania; Freiburg, West Germany; and Chicago. She went through a phase of figure drawing and then concentrated on a series of acrylics done on a canvas of fabric, such as tablecloths woven by home weavers in Lithuania. "These linen weavings are miraculously beautiful," she exclaims. Balukas feels grateful to the weavers who created them and has dedicated her own creations to their memory. The original patterns are preserved by Balukas as sacrosanct. But she reinforces the design with acrylics or oils, enhancing it with her own choice of color. The white-on-white flax pattern becomes vivid with superimposed colors and comes to life as a new creation. The first paintings in the series were timid and did little to alter the original design. Later ones were bolder and introduced patterns which emerged from her imagination. Now her art depicts the oriental symbols of meditation and self-awareness the mandalas. She translated this Buddhist symbol into her own vocabulary and fills it with Lithuanian symbols and colors. Onto squares and lines of the original linen she inscribes circular or enclosed shapes in the manner of the mandalas. Balukas is probably the first Lithuanian artist to create successfully such hybrids by joining ethnic folk art motifs with images of oriental mysticism.

Danguolė Stončius-Kuolas: "My prints are a revelation of my past experiences. Since those experiences were the result of growing up culturally and spiritually as a Lithuanian, from having Viktoras Petravičius as my first art teacher, from the tremendous sense of oneness with printmakers in Lithuania, experiences after a visit there, I feel that my work evokes my heritage. "I feel that there is an ongoing process of coming to terms artistically with that which my background brings forth. Change does not deny Lithuanian tradition, but rather we come to understand tradition differently because life and times change.

"Therefore, if one looks for traditional decorative motifs in my work he will not find them. However, one can find repeatedly a searching, a breaking of boundaries, an entering of passageways that reflect an introspective attempt to recall memories and to provide for the viewer the opportunity to make new memories."

Eleonora Marčiulionis. Marčiulionis has spent a lifetime working in ceramics. She chose this medium early in life: It gave me a sense of totality which no other medium was able to offer drawing, colors, sculpture all in one."

Marčiulionis uses bright, vivid colors on her clay sculptures. Most of her works are three-dimensional or framed bas-reliefs. The subject matter ranges from nature to biblical themes. Her vases and figurines (which she sometimes dresses in Lithuanian folk costumes) are vehicles for expression of her ethnicity. In her religious art she has produced stations of the cross and madonnas. Her madonnas appear in prayerful poses expressing the artist's own deep spirituality and the great trust she has in Our Lady's protective powers. Her ceramics have been characterized as full of playful vitality her vases dance in joy; her figurines wobble in comic steps; the madonnas are decorated in exotic and heavenly splendor.

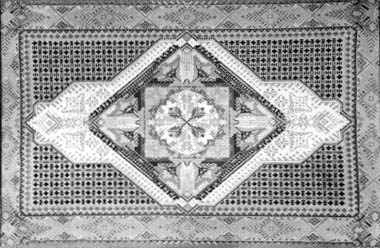

Janina Marks (Monkutė) has been working recently on a series of cotton and wool tapestries with ancient Lithuanian ornaments as subject matter. "Composition with Ancient Ornaments" depicts the design of a pin from 10 c. AD found recently in a Lithuanian grave mound. Primitive art motifs have been her main obsession in all her creative work and in her art collecting. This is a result of a life-long interest in Lithuanian mythology, folk art, folklore, and songs. Historically Janina Marks went through several phases of her development as an artist, which included studies in architecture, rug weaving, theater, abstract painting, pop art, op art; but she was not able to engage in any of them wholeheartedly. The more she painted, the more her paintings looked like designs of imaginary rugs. Soon she began to feel a distance between the brush and the canvas, while her woven tapestries became more and more intimate and personal. She felt that in weaving one is able to actually touch the color and feel the texture. Naturally she moved into painting with fiber after discovering the unusually rich color combinations of the old Lithuanian woven fabrics. The feeling of touch as opposed to simple seeing became a major factor in choosing this new media of expression. Her most recent wall hanging, "Knotted Blue-jeans," has a fiber texture which reminds her of the rough surface of ancient cooking pots.

Through the eyes of primitive artists, both Lithuanian and others, Janina Marks has found her own way of looking at herself and the outside world. Her work is an affirmation of her commitment to the folk art of various nations, especially to the heritage of her own.

Jadvyga Paukštienė, who is a legend among our artists, with many international prizes and awards, calls herself an expressionist painter in the sense that she creates her images impulsively. The images are first acquired in the shape of an idea which suddenly appears in her consciousness; she then works feverishly until the "idea" is embodied in a painting with visual and thematic content.

Subjects that keep recurring are family life, especially children and their mothers, nature and its flowers, the nude (which for her is an object composed entirely of colors: "The human body is nothing but colors"), and still life. The main, underlying idea for all this is Man, the rest is background." Color is her medium, which in her oils reaches the effect of three-dimensionality with a surface texture all her own. Lithuanian subjects? "Yes," she answers. "They are in my blood" Madonnas with Lithuanian features, folk-costumed children, and dancers abound.

Pranas Lapė has recently illustrated two books of Lithuanian poetry "Augintinių Žemė" (The Land of Adopted Children) by Algimantas Mackus and "Pakelėje į pažadėtąją žemę" (On the Way to the Promised Land) by Antanas Gustaitis. He also has been working on themes based on Donelaitis' poetry. When asked about the influence of Lithuanian ethnic traditions on his art he wrote the following: "Without doubt our art is different from that of the Latvians, Estonians, Russians, Poles, or Germans. Why this is so it is difficult to explain in a short statement. The differences between these nationalities are affected in part by differences in geography, living conditions, and national character. All of this is mixed in a complicated weaving which is hard to decipher. Artists do not learn from nature but from one another. Thus artists living together with the confines of the same nation, in the same territory, and being exposed to the same historic circumstances, have a natural tendency to form groups, units, and 'schools' through which unique art forms emerge. If this tendency continues to develop and grow over a longer period of time, it deserves to be called tradition.

"We Lithuanian artists living in the United States of America have not reached the point where we could say we have formed our own school or a Lithuanian tradition. We are scattered and separated by long distances; each is exposed to different types of experiences, ideas, and circumstances of life, was born and raised in Lithuania. I am conscious of being Lithuanian, not necessarily in a political sense or as a member of some insignificant 'ethnic' group. Just how much of Lithuanianism there is in my paintings 1 do not know. When I paint, I do not paint with patriotism but with a brush and paint. In my art I do not try to solve any 'ethnic' problems, but I do my best to adhere to the axioms which are required of good art. I live in natural surroundings, in a climate similar to that of my native Lithuania, where the seasons change exactly as they did in my home country. It is obvious to me that most people feel the changes of seasons in nature. These changes affect me even more. I organically feel them in my bones. I personally experience the different moods they bring and, of course, depict them on my canvases. I do not mimic nature. Since a 'mood' is said to be abstract, it naturally calls for the same treatment in art. But I have no intention of painting pure geometric 'squares' to express my emotions. Geometric abstractions are more akin to speculations which should be left to philosophers. I am inspired by Lithuanian poets who depict the landscape of my homeland. I enjoy reading the classic poetry of Donelaitis, Baranauskas, Maironis, and also modern poets such as Henrikas Nagys, who now lives in Canada. Sometimes the poets give me a push, other times I allow their moods to play on my canvas. Thus, as the Lithuanian saying goes, 'one who jumps into a puddle, does not come out of it dry,' so it is with me. I was born in Lithuania, and will always remain Lithuanian, even when I happen to be living on the other side of the lake."

Viktoras Petravičius, "Spring Rites of the Gods," 1988, oil graphics, 35"x52.

Veronika Švabas, "Sadutė," 1987, linocut, hand-colored, 26"x21"

Vytautas Ignas, "The Catch in the Sea of Kuršiai," 1988, linocut, 30"x19"

Janina Marks, "Composition with Ancient Ornaments," 1988, cotton and wool tapestry, 42"x33 1/2"

Vanda Balukas, "#15 Lake Michigan Mandala," 1975, acrylic on linen, 49"x74"

Zita Sodeika, "Into the Future," 1987, acrylic, 26" x 23"

Pranas Lapė, "Jau saulelė vėl atkopdama budina svietą"

(The Rising Sun Wakened

the Earth), 1987, acrylic on canvas, 72"x68"

Pranas Gailius, "Donelaitis' Sermon at his Anniversary Mass" page 7, 1983-1986,

embossed paper 15"x22", lyrics by Kazys Bradūnas

Antanas Tamošaitis, "Criss-crossings in the Cosmos," 1987, oil 36"x24"

Eleonora Marčiulionis, "The Coronation of the Madonna," 1987, clay, 30"x24"

Jadvyga Paukštienė, "Nude Woman Relaxng," 1987, oil, 24"x19"

Danguolė Stončius-Kuolas, "Out of iBounds," 1987, Collograph, 12 1/2"x12"

Jurgis Daugvila, "Lithuanian Chapel," 1988, wood, 52"x15"