Editor of this issue: Saulius Sužiedėlis

Copyright © 1989 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 35, No.1 - Spring 1989

Editor of this issue: Saulius Sužiedėlis ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1989 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

CURRENT EVENTS

The Summer of 1988 and

the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in Lithuania

by Asta Banionis

General Secretary Gorbachev's call for economic restructuring and democratization found a particularly receptive audience in the Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The summer of 1988 was a revolutionary season in the Baltic. Gorbachev's rationality made sense to people tired of living in fear and numbed by useless sloganeering. In the Baltic, Gorbachev found people willing to take a risk on him and his message. Human energies and talent sparked a revival of the human spirit and the peoples of the Baltic republics discovered a self-confidence long thought extinguished by Stalinist repressions begun almost 50 years ago.

Summer, 1988 witnessed mass movements in the Baltic. Environmentalists, religious activists, academicians, and even political activists rallied hundreds of thousands of people to "events", demonstrations and meetings. A recent visitor to Lithuania remarked that the whole nation had become one great debating society; even a "Hyde Park" corner was inaugurated in the capital city of Vilnius. Popular movements were born in each of the Baltic republics both to harness and accelerate this new energy.

In Lithuania this popular front is called the Lithuanian Movement for Support of Perestroika, usually known as "the Movement" ("Sąjūdis"). Begun on June 3, 1988 by an informal group of academics who called themselves an "Initiative Group", Sąjūdis on July 9 was able to mass over 100,000 people at a meeting in Vingis Park to "welcome home" Lithuania's delegates to the XIX Communist Party Conference in Moscow, and to "share some ideas with them". The Initiative Group itself was surprised by the overwhelming response they received (one quarter of the population of Vilnius attended the open-air meeting). Only a few members of the Communist Party leadership met the challenge to participate in the meeting. But this four-hour meeting gave Sąjūdis its first mass forum and demonstrated to the Communist Party leadership that "there was a new kid on the block" to be reckoned with.

Sąjūdis seeks to be inclusive of the population and therefore finds ways to utilize people's talents. The rhetoric of Sąjūdis spokespersons is sometimes overwhelming to Western observers in its expectations of the best in human nature. Sąjūdis leaders (now formally elected since the first national congress held October 21-22, 1988) rally their fellow citizens to be the most creative, the most energetic, the most giving, the most charitable, etc. Sąjūdis chapters have sprung up all over Lithuania supporting environmentalists, human rights demonstrators, cultural projects and local activists fighting corruption. Sąjūdis now estimates that it has a core of 150,000+ activists in its ranks with a program and statutes. Its activists have even proposed a draft for the new Constitution of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic.

While masses of people have flocked to Sąjūdis, two long-standing organizations in Lithuania have struggled with Sąjūdis' embrace: the Lithuanian Freedom League (LLL) and the Lithuanian Communist Party. The Freedom League was formed by Lithuanian human rights activists in the mid-1970s when the Helsinki Accords gave new impetus to the human rights movement in the U.S.S.R. Along with the Lithuanian Helsinki monitors, the activists of LLL fought an often lonely battle against the repressions of the KGB and Soviet legal system. Many members of the LLL have long suffered what is worst in the Soviet system: forced unemployment (blacklisting), beatings, constant surveillance, concentration camps, torture, psychiatric treatment and internal exile. They have been the ones always willing to risk death, and have been the most uncompromising in their principles. The Lithuanian Communist Party, on the other hand, has been described as a blend of opportunists, true believers, pragmatists and idealists. Annexed to the Soviet Union in the early days of World War II through military force, Lithuanian society has struggled with various survival techniques over the last 50 years. Along the way, the foreign Communist Party apparatus has been filled with more native-born members; some progressive, some reactionary.

A Peaceful Demonstration

Black-ribboned flags at the August 23,1988 Commemoration of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in Vilnius.

The Crown of Barbed Wire at the Molotov-Ribbentrop Commemoration. (Lithuanian Information Center)

Both these groups who have staked out opposite poles of the political spectrum and occupy opposite ends of society's hierarchy now have to deal with the great middle which is no longer a mass devoid of thought or direction. The leaders of Sąjūdis have both awakened and harnessed the energy of the masses.

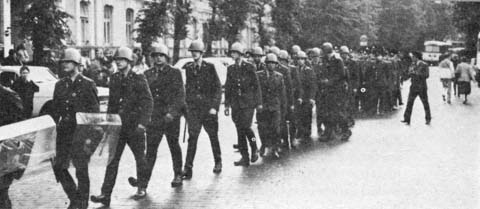

There were many demonstrations, rallies, and meetings in Lithuania this past summer, but one is particularly illustrative of the dynamics among these three groups: the Party, LLL, and Sąjūdis. On September 28, 1988 the Lithuanian Freedom League (LLL) called for a memorial service in Gediminas Square (a main square in the capital of Vilnius) to commemorate the tragedy of the Molotov-Ribbentrop secret protocols which assigned Lithuania to the Soviet Union in 1939 and cleared the way for annexation. Sąjūdis had sponsored a similar memorial service on August 23, 1988 which had over 250,000 participants, and was broadcast in its entirety over Lithuanian television the following day. Therefore, it was an unexpected change of policy when the Lithuanian Communist Party chose to forbid the September 28 service on short notice, with no warning to the public.

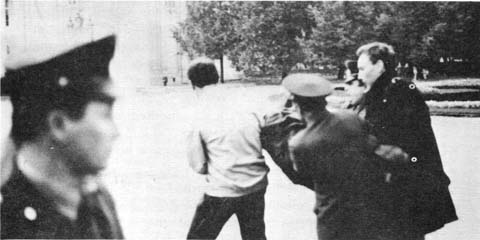

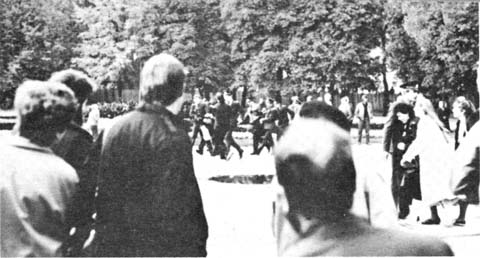

The Violent Response: The Demonstration of September 28, 1988 in Vilnius.

Over 5,000 people had assembled by 5:00 PM to attend the memorial service when the militia arrived to disperse the crowd. Although the crowd was disbanding peacefully, the militia was eager for a fight and confirmed reports now tell us that the militia men armed with batons beat participants and passers-by. They beat women and children, and struck quite a few heads into the sides of vehicles and buildings. Throughout the night roaming bands of militia attacked civilians in the streets. Hundreds of people were injured and over 28 arrested.

In the early morning hours of September 29 a number of LLL members resumed a hunger strike which had been ended earlier in Gediminas Square to protest the illegal acts of the militia. By 5:00 AM the militia arrived to arrest these hunger strikers and their supporters. By 9:00 AM members of the Sąjūdis Initiative Group were demanding the release of all those arrested. They attempted to meet with the Lithuanian Communist Party leadership to demand an explanation for the unprovoked brutality and punishment for the militia involved. Sąjūdis members began to picket the Lithuanian Communist Party headquarters. By 8:00 PM members of Sąjūdis had negotiated with the Central Committee of the Lithuanian Communist Party, and the arrestees of September 28-29 had been released.

But the events of September 28-29, 1988 continued to reverberate within society. On October 4, 1988, at the 13th Plenum of the Lithuanian Communist Party, Bronius Genzelis, a member of the Party and the Sąjūdis Initiative Group called for the resignation of Lithuanian Communist Party chief Songaila. Invoking the conscience of the Communist Party, Genzelis held Songaila and other top officials responsible for the shameful events of September 28-29 which put the lives of the people in danger and brought disgrace on the Party and the Republic. He called on Songaila to resign his leadership post and called on such members as Interior Minister Lisauskas to be purged from the Party cadres.

Subsequent events have proved Genzelis to be a brave rather than a foolish man. Approximately 2 weeks later, First Secretary Songaila resigned, and the first constituent congress of Sąjūdis meeting on October 21-22, 1988 was addressed by a new First Secretary, Algirdas Brazauskas. Brazauskas had been one of the few LCP leaders to address Sąjūdis in the past, and he appears to have been the key Party negotiator during the confrontations of September 29.

The American foreign policy establishment has been slow to react to the new democratic movements in the Baltic republics. The fate of the Baits has been viewed as an untidy matter left over from WW II easily tolerated by both superpowers. But the Baits have demonstrated that the "matter" is no longer so easily managed.

The roots of this blossoming of democracy are buried deep in the soil of 1939 when Lithuanian society was independent, so it is not surprising that the critical event which lead to this past summer's unfolding was an earlier demonstration against the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. On August 23, 1987 the Lithuanian Freedom League held a rally at the Church of St. Anne in Vilnius. The meeting was harassed by the militia, but the Lithuanian Communist Party followed this up with an intense publicity campaign against the memory of the "bourgeois nationalist state of Lithuania", the society destroyed by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Many Sąjūdis activists will now tell you that this campaign mobilized a backlash against the existing Lithuanian Communist Party apparatus which had clearly identified itself with the Stalinist, anti-Gorbachev elements of Soviet society. Throughout the winter, Lithuanian society slowly organized itself into discussion and working groups which by the summer of 1988 had found a common language. When the Party chose to confront the masses through violence again on September 28-29, the people were ready. Sąjūdis had taken shape and defended the interests of the people.

Students of democracy should pay serious attention to the peoples of the Baltic republics this coming year for they will witness a noble and compelling experiment; an attempt to wrestle the tools of government away from the hands of a minority and back to the hands of the majority. Will Americans be attentive to this struggle for democracy this year? The peoples of the Baltic surely hope so.

The Speech of Justinas Marcinkevičius1 on 23 August, 1988

Forty nine years ago Moscow newspapers carried the following photograph on their front pages: Stalin is raising a glass of champagne while congratulating Molotov and Ribbentrop who had just signed the nonagression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union; this pact, which the Communist and Social Democratic parties of Europe, the largest trade unions and the progressive leaders of society and culture, had refused to understand and justify. Judging from how this treaty was praised and glorified in the Soviet press of the time, we can assume that the Soviet people viewed it with reservation as well.

The people were right. After a week the champagne in Molotov's, Ribbentrop's and Stalin's glasses turned to blood: The Second World War began. Whether we want to admit this or not, whether we like it or not, objectively speaking, the nonagression pact between the Soviet Union and Germany untied Hitler's hands and assured him of peace and quiet in the East. This allowed him to direct his main forces against the West and to occupy almost all of Europe within a short time. As if this were not enough, according to the terms of the agreement, the Soviet Union sent Hitler trainloads of oil and other strategic goods and, through the Comintern, destroyed the front of the antifascist forces in the West. In Moscow they arrested and murdered some of the activists of European Communist parties (among them the Lithuanian Zigmas Angarietis), turned away from the leader of Germany's working class, Ernst Thaelmann, whom they could have helped and snatched away from the death camp. And all this was accomplished by the first socialist state in history to which the progressive world was looking with hope and trust. And after a year and a half Hitler stood at the borders of the Soviet Union with virtually the entire economic and military potential of Europe at his back; he stood, one might say, doubly strong, more terrible and threatening. This is why the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 23 August, 1939 must be considered a strategic error of Stalinist foreign policy and the true beginning of the Second World War. This is why we unconditionally condemn this pact.

Today it would be pointless to discuss how the Second World War and the fate of European nations would have turned out had this unfortunate agreement not occurred. Unfortunately, it is there: a red and brown blot on the history of the Soviet Union. Some point to it with joy; others with rage; still others with pain and sorrow. This is because the greatest and most terrible flame of war, which consumed tens of millions of lives, erupted from this blot. I ask you to remember all of them, the people of all nationalities, of all religious and political convictions; all who died with weapon in hand, those who died of hunger, who perished from military and political terror, whose lives were extinguished in exile or political emigration. I ask you to think about all of them and to honor their memory by a minute of silence.

Whatever our politicians, historians and ideologues say or however they explain the international situation of that time, one thing is clear: the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact is a document of disgusting international banditry because it is also based on secret protocols whose essence some of us learned earlier, and some later. . .

After inviting the Lithuanian foreign minister to the Kremlin, Stalin stretched out a map and bluntly laid out the basics of the partition, while Molotov cynically declared (I quote according to the manuscript of the memoirs of the last foreign minister of the Republic of Lithuania): "Any imperialist state would occupy Lithuania and that would be the end of it. We will not do that. We would not be Bolsheviks if we did not look for new ways. . ."

Save us, oh Lord, from such Bolsheviks; we all know what their "new ways" were like.

Political cynicism is immeasurable, especially when politics is carried out in the name of the people but without their knowledge. The newest example of such politics is the entry of the Soviet Army into Afghanistan. How much pain and tears this has caused, how it has ruined the international prestige of our land, and how much wisdom and political will is needed by those who are now determined to untie the knot of Afghanistan.

One hundred and five years ago the newspaper of our national rebirth, Aušra (The Dawn), chose as its motto the ancient Roman saying: "Homine historiarum ignari semper sunt pueri." In Lithuanian that would be: People who do not know history, always remain children. How relevant this is today! Yes, truly you and we are children, because we do not know our real history, either the old, or the most recent history. And we do not know it because it is hidden from us; it has become the handmaiden of politics, because it must justify political mistakes. . . this does no honor to history. Not long ago the secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR, Alexander Yakovlev, visited Lithuania and, while meeting with Party activists said: "Open and conscientious historical research: this is our victory because it shows the moral strength and maturity of society." Unfortunately, we still very much lack these moral forces and maturity. The recent publications in our Republic concerning the problems of the postwar class struggle, the Stalinist repressions and collectivization are proof of this. With this in mind, I propose to include the following demands into the resolution of this meeting:

1. To publish the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact with its secret protocols and maps in the Soviet press and to condemn the treaty for its crude and shameless violation of international law, the violation of humanity, as well as the breaking of treaties and agreements.

2. To establish by law a statue of limitations on the secrecy of documents, such as is accepted among the democratic states of the world.

3. To open the doors to all archives for scholars, literary figures, journalists and everyone who is interested in history.

4. To publish a supplementary volume of the "Sources of History of the Lithuanian SSR", which will present documents about the most recent history of our country without the ideological suppression of evidence.

5. To prepare a new program and textbooks for Lithuanian history in the secondary schools.

Long live this nation, in free communion with its own history!

Translated from the Lithuanian

by Saulius Sužiedėlis

Translation of speech by Sigitas Geda2

at Molotov-Ribbentrop Memorial Service in Vingis Park August 23, 1988

My dear Lithuanians and all other proud nations!

I would like to begin my remarks this evening with the words of John Reed, the famous, early-twentieth century American journalist, romanticist and Utopian, who described a 1917 meeting in Petrograd during which Vladimir Lenin addressed the excited crowd with the "Proclamation to All Nations at War and Their Governments." Here's a short citation from this fundamental text of the Soviet state:

"Annexation, or the occupation of foreign territory, according to legal democratic beliefs and particularly according to working class beliefs, as the government understands it, exists when any small or weak nation is joined to a large or strong state without that nation's clear and free declaration of intent and agreement, not withstanding that this annexation is done by force, notwithstanding the stage of development of the forcibly annexed nation. Finally, it does not matter if this nation lives in Europe or in faroff continents.

If any nation is held within another country's borders against its expressed will, despite what may be demonstrated in the press, peoples' meetings, party decisions, street rioting, or revolt against national oppression, but without the right to free elections, with the army of occupation totally removed from the territory of the weaker nation and without the slightest pressure to resolve the question of statehood, then that resulting union is annexation, i.e., seizure and violence.

Now or when you return home this evening, reread this text, and reflect upon its implications and draw your own conclusions according to your own conscience, and now permit me to move on to other issues.

When Leo Tolstoy began to write "War and Peace" sixty years had passed since the great war of 1812. Sixty years! What could this mean and why do I choose to begin my analysis this evening with this event? Because next year will mark 50 years from the decisive year of 1939, which we are assembled here today to commemorate. And, until 1999, i.e., the end of this century or the end of the world, we should be able to find a way to understand the events of the middle of this century. After that it may be too late. It could come to pass that nothing of the earth will remain, i.e., the planet and the human race will disappear.

And now I would like to speak in the style of biblical parables or a simple allegory.

A person lives, be he small and weak, nevertheless a free man, and he has a roof over his head, he has his own land and his own woman, and then he is surrounded by two big and strong neighbors, many times stronger than himself. And these two neighbors approach him on a clear August night, much like this evening, and they say to this man alone: "We will take away from you your roof above your head, we will take from you your land and your woman, your children. . . We will distribute your possessions, everything that belonged to you, your parents and your ancestors, and you will be pleased and happy. . ."

This small man begins to shiver from fright (something inside of him wants to resist, or to believe that everything is still all right), but does this small and weak man, or anyone standing behind him, maybe his guardian angel, see through these two bandits. What should this small and weak man do?

This was not just this one man's dilemma, nor just our collective dilemma, but a question faced by many people living in small territories with small populations during 1936, 1937, 1938, and 1939.

"Defend yourself", you might counsel, not smelling the blood and the gunpowder, and you would be right.

"Counterattack" you could say, not imagining what kind of prisons were prepared for you, and you would be right.

Like a weasel, this small man should rip out the eyes of these two villains, but he understands that he can do something else. He knows that he must collect all the strength in his quaking body, all the strength of his God-given spirit, his willpower, and his intellect if he is to survive and if he is to keep his roof over his head, and his land in which his ancestors' bones rest, and his children who are still young and need to be protected.

Let us try to understand this man as we observe him through a murky fog of 49 years with his face beaded by sweat; then we will come to know that critical year of 1939, what happened before it and after it, how our parents and brothers and sisters felt, how our grandparents living near Meteliai and the [river] Dubysa felt, and we will hear the voices of our living and dead grandmothers seated under the apple trees described by [the poet] Mačernis.

Let us forget for a moment tales of our noble ancestors whether they be descended from the Himalayas or risen from the lost islands of Crete, let us forget the myth of Palemonas and the enlightenment of our European ancestors and let us rather put ourselves in the skin of those two strong men mentioned earlier. Or even better, let those two bullies, having divided up their weaker neighbor's wealth, find themselves in the threatening shadow of two other men ten times bigger and stronger than they, and let these two new giants smother them with the same "fatherly love" they had promised their smaller brother.

What kind of fear and terror would we find in their eyes?

I'm not suggesting that this allegory will make things better in our imperfect world, but let the people and nations who have great power and influence in the world try to spend a little time in the skin of a Lithuanian.

I just want to remind us how relative strength and power can be, the paradoxes of victory and defeat, the illusion of annexations, liberations, and consolidations. We should also consider what was won by those who tricked us and what we won, the sons and daughters of those who almost 50 years ago lived clenching their teeth.

The villains won nothing, and we lost nothing! It is only silly illusions and weaknesses which interfere with our understanding of this fact; the embers of our nation's desire for freedom and self-determination, long smoldering in the depths of our soul, have been rekindled. And the small, frightened man looks at us from this faded 1939 photograph, and his violated daughters left on the banks of the Laptev sea and his children who have found their way home to Lithuania testify that this may have been the only path our nation could have taken so that its land and its language could survive and one day arise.

If the Germans don't believe this, then let them remember the crushing sounds of the marching legions of Julius Cesar and Marcus Aurelius, and the terror in the eyes of their ancestors as they stood defeated on the banks of the Rhine.

If the Russians don't believe this, then let them remember the Twelfth century and the Mongol invaders which descended upon the Russian countryside like a plague of locusts.

Two generations would pass from this earth before the word "Tartar" ceased invoking panic among the Slavic tribes; we also needed not quite two generations. Yes, that small weak man who tilled his sacred soil, had a great deal of fear drilled into him and his children. But we shouldn't hesitate to correct the words of our enlightened writer of the nineteenth century, Vincas Kudirka, who wrote that you could always identify a Lithuanian by his quivering knees. . .

If we look at history and view the panoply of nations that have lived since time began we will find many a populous nation that has quaked in fright no less than we Lithuanians.

"Jedem das Sein" the Germans were fond of writing over their concentration camp gates.

"Allah wants it this way", the Stalinist inquisitors would urge us as they handed you a false confession to sign.

Yes, we all take back what is ours. No more, no less. Only that which is due us, measured and weighed. This age, this century has already doled out enough for the Lithuanians, the Poles, the jews, the Russians and the Germans. Enough has been measured out to the nations of the Caucasus and the Near East all the way to Afghanistan which chokes on the tears and blood of the children we ourselves have given birth to.

Therefore, haven't we arrived at an age where we need universal peace? Isn't it time that we told the powerful nations of the earth that it is time for peace? This is what we, standing here in this wind-swept land near the Baltic Sea, should tell the nations of Europe and Asia.

Don't our mistakes and our sins have a common yardstick? Surely we will find a point in common, surely we can share repentance. If not, then there will be no twenty first century. The words of the ancient Hebrew prophets will not come to pass, nor the prophecies of Virgil, St. Francis, nor Joachim of Fiore.

We will see no New Testament, known as the Testament of Love, and the new age, prophesized as the "Age of Lilies", will never dawn.

We haven't assembled here today to draw up an accounting, nor do we seek revenge, we have come to commemorate that which happened to Lithuania, Poland and this entire corner of the world. How they carved us up, how they wanted to bury us. How they relished dividing up the world!

Where is the proud philosopher Nietzche. . . who tried to dethrone God so that he could take his place? Where are the narcissistic Russian messianists, those devils, whom Fyodor Dostoyevsky exposed? They no longer exist. In their place we now have Adolf from Austria and "that clever fellow from the Caucasus" with a cockroach-like mustache and jacket buttoned to the neck (the uniform later appropriated by Mao).

Let us feel sorrow for them because they too were born of human parents. We have the right and the duty to pity them. We survived, we are alive. They exiled you, but you returned home. They tortured you, yet you did not break.

And let us pity all those who want to continue all this. Let us forgive all those legitimate and illegitimate children of Hitler, Stalin, Beria, Molotov and Ribbentrop who wielded the instruments of torture. Using lies and deceptions they want to keep us in the dark. During the endless night let us pray for them; it will make us stronger.

There stands a man from Palanga, Krokialaukis, and Lazdijai. He has sight in but one eye, he is deaf, he was left but one tooth by the NKVD men. His sick child, his sixteen year old daughter from the Pabrade orphanage will never speak. This is the price which has been paid and we will continue to pay; but Lithuania has awakened, and is rising. A new Lithuania, great and yet unseen; perhaps only in our dreams. All of our speeches, sermons and directives mean nothing for her now. She herself will know what is to be done, having considered it calmly and wisely: How, where and with whom she will travel in this world. Let us all trust in her. Not to believe in Lithuania today, means not to believe in wisdom, conscience, freedom, and honor.

Translated by Asta Banionis

The Speech of Historian Gediminas Rudis on 23 August 1988

at the Commemoration of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in Vingis Park (Vilnius)3

On August 23, 1939 the leaders of the two most reactionary regimes of the twentieth century, Nazism and Stalinism, found a common language at the negotiating table. In violation of the most basic norms of international law, they partitioned sovereign states into spheres of interest (within the latter's knowledge). The fruits of this bargain were not long in appearing. Soon Poland was crushed. In Brest there was a joint victory parade: Soviet and Nazi troops amiably shook each other's hands. Moreover, Soviet propaganda named the British and French imperialists as the aggressors who had initiated the Second World War. After this the war between the Soviet Union and Finland began; and finally in June of 1940 a revolutionary situation" matured in the three Baltic States: Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. It must be said that the so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was quite expensive for the people of the entire Soviet Union as well. Who can now list all the lives which were wasted by the misperceptions of the leader of nations."

The enormous gathering shows that we understand how fateful for Lithuania were the transactions of the leaders of Nazism and Stalinism. In fact we cannot explain events in Lithuania outside the context of Soviet-German relations during 1939-1940. It is for good reason that there are such vigorous demands for the publication of the secret protocols of agreements between the USSR and Germany. There can be no doubts about the soundness of such demands. However, the historians' excuses that they are helpless are without foundation. These protocols have long since been published abroad, and now they have appeared in our own press. [For some] it is enough to behave as if these publications do not exist. We need a scholarly analysis of the credibility [of the protocols]. Society is no longer satisfied by the traditional concept of the socialist revolution in Lithuania in 1940. Thus it is essential to have a principled, open scholarly discussion without any restrictions. In my opinion, there were no generally acknowledged characteristics of a revolutionary situation in Lithuania in 1940. One thing that raises no doubts is the crisis at the top." But who deepened this crisis? After all [President] Antanas Smetona did not flee to Germany pursued by a rebellious people. It was not the people who deposed the government of [Prime Minister] Antanas Merkys. The crisis at the top was organized by the Kremlin and not very cleanly at that; they left many traces. Every single one of the accusations contained in the Soviet Union's ultimatum to Lithuania on June 14, [1940] was fabricated, even absurd. Neither Lithuania nor the other Baltic States threatened the Soviet Union with war. And the alleged kidnappings" of Red Army men in Lithuania were pure fiction.

Some historians maintain that Smetona's foreign policy adventures hastened the collapse of the Nationalist regime. In February 1940 the Director of the State Security Department A. Povilaitis traveled to Berlin to request a [German] protectorate, allegedly at Smetona's order. This contention, so firmly rooted in Soviet historiography, raises considerable doubt. The only source on the results of the Povilaitis mission is the interrogation protocol of Povilaitis himself dated March 13, 1941.4 We know very well what were the interrogated Povilaitis had so wished, he would have confessed to having dug a tunnel from Kaunas to Vilnius.

One could talk for a long time about how Molotov, Dekanozov and the other executors of Stalinist policy behaved as they organized the change in Lithuania's political regime. I will relate but one episode. On June 14, 1940 Lithuanian Foreign Minister Juozas Urbšys attempted to argue that it was unclear how [Interior Minister] Skučas and Povilaitis could be brought to trial.]5 Molotov stated: If your jurists cannot find an article [in the legal code], then our legal experts will search for some articles under the Lithuanian code, even if for treason." Then he added: For they are real traitors to Lithuania's interests." Molotov knew what he was saying. At the time, however, Urbšys did not suspect that the jurists who arrived from Moscow would find articles of the code not only for Povilaitis and Skučas, but for him as well. I do not intend to idealize either the Nationalist regime or its last government. You know the social class whose interests it defended. However, there were honest and moral people in that government. In my opinion, the foreign minister of the Republic of Lithuania, Urbšys, was such a person. And so I would like to wish him well.

Historical scholarship owes a great debt to society. However, we cannot repay this debt by simply expelling the spirit of dogmatism and Stalinism. I wholeheartedly support the idea of Soviet historian Afanasyev that we will not shake Stalinism until we finally understand that science and knowledge, including history, is created in laboratories and departments, and not at congresses or in Party committees.

Translated by Saulius Sužiedėlis

Speech by Professor Liudas Truska on 23 August 1988

at the Commemoration of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in Vingis Park (Vilnius)6

Honorable participants of this gathering!

I have doubts whether the Soviet Union's benefit from the 1939 treaty was as great as most historians claim. Even if it were, the Baltic States and Poland paid a very great price.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was a funeral bell for the independence won with such difficulty by the Baltic States in 1918-1920. It is even more outrageous to think that all the states founded after World War I (Finland, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary) still exist. It is only Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia that have disappeared from the political map of Europe.

They want to convince us that the Lithuanian nation gave up its sovereignty of its own accord and asked Stalin and Molotov for protection. This is not true. Independence is the greatest treasure and the five-thousand-year history of humanity has not witnessed a single case of a nation willingly giving up its independence.

Stalin sought to retrieve the lands which had belonged to the Tsarist empire before World War I. It was this fact that determined the fate of the Lithuanian nation in 1940. Lithuania saw a neatly-arranged performance. Its chief stage manager was [Vladimir] Dekanozov, Beria's devoted comrade-in-arms who arrived in Kaunas on June 15, 1940 and stayed there for an entire month. (Together with Beria, Dekanozov was shot in 1953. Such was the man into whose hands the Lithuanian nation fell during the summer of 1940.)

Militia in action at the Demonstration of September 28, 1988 in Vilnius.

Did Lithuania have an alternative in 1940? Yes, it did! Professor Vincas Krėvė-Mickevičius, the Chairman of the Council of the People's Government and Minister of Foreign Affairs, who was supported by Finance Minister [Ernestas] Galvanauskas, Defense Minister [Vincas Vitkauskas], and partly by Agriculture Minister M. Mickis, proposed to Molotov that, like Mongolia, Lithuania should remain a separate state.

Looking at it rationally, this offer corresponded to the interests not only of Lithuania, but the Soviet Union as well. The Red Army would have remained in Lithuania, while the economy of the Soviet Union would have profited far more from the State of Lithuania than from the ruined economy of a Union Republic.

Nevertheless, Stalin and Molotov did not concede Lithuania even limited statehood.

Molotov declared to Professor Krėvė-Mickevičius on the latter's visit to Moscow at the end of June [1940] that the Russian Tsars, beginning with Ivan the Terrible, pushed toward the Baltic Sea and therefore it would be unforgivable to miss this chance which may not repeat itself. He continued: Small states will have to disappear in the future." That's why Lithuania must join the family of Soviet Republics.

Is not the Stalinist policy toward small nations similar to the policy of Fascism? The difference is only that the Nazis were planning to annihilate small nations physically, whereas Stalin and Molotov planned to do so by fusing them with large nations.

The direct consequence of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, the liquidation of the Lithuanian State, brought about countless misfortunes for the Lithuanian nation: violence and the use of force, mass deportations and massacres, the destruction of the economy and culture, the humiliation of the nation and the ruin of national culture. We must realize that all the inhabitants of Lithuania, the Lithuanians, Jews, Poles and Russians who were deported, tortured to death in prisons, who perished in the postwar struggle: They were all victims of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

The time for repentance has come; a repentance which purifies the individual, the society and the nation. Historians must repent more than anyone else. As a historian I am ashamed that for such a long time we have not been telling the people the whole truth, only half-truths or even less than that; and this is the biggest lie of all. The society should exert its influence and place pressure on historians, to demand that they should write the truth and nothing but the truth on all questions.

1 Justinas Marcinkevičius is one of Lithuania's leading and most popular poets. His was the first speech at the commemoration of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in Vilnius, following the introductory remarks of Prof. Vytautas Landsbergis, presently head of the Lithuanian Movement, Sąjūdis.

2 Sigitas Geda is a popular poet of the younger generation who had once been ostricized by the Party. He is a founding member of the Sąjūdis. Geda's writings reflect an interest in Eastern religions and mystical Christian themes. He now edits a new Christian periodical in Lithuania.

3 The original speech is published in Atgimimas, No. 1 (September 16, 1988).

4 In fact, Western sources including Dr. Werner Best, a participant at meetings with

Povilaitis, indicate that Povilaitis seems to have approached the Germans about assistance in the case of a Soviet threat to Lithuania. On this see Seppo

Myllyniemi, Die baltische Krise 1938-1941 (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1979), 107. However,

Povilaitis' statements under interrogation on March 13, 1941 concerning Smetona's request for a Reich protectorate and the President's alleged willingness to establish Nazism in Lithuania are inconsistent and thus highly suspect.

5 The prosecution of Skučas and Povilaitis for their part in the alleged kidnapping" of Red Army personnel was one of the demands of the Soviet government in its ultimatum delivered to Lithuania on June 14, 1940.

6 Liudas Truska is a social and economic historian at the University of Vilnius. This translation is adapted from the English-language, The Congress Bulletin, No. 1 (October 21, 1988) published during the Constituent Congress of the Lithuanian Reform Movement, Sąjūdis." The original is published in

Atgimimas, No. 1 (September 16, 1988).