Editor of this issue: Antanas V. Dundzila

Copyright © 1990 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 36, No.1 - Spring 1990

Editor of this issue: Antanas V. Dundzila ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1990 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

MIKALOJUS KONSTANTINAS ČIURLIONIS

Lithuanian Composer and Painter

ANDREA BOTTO*

The study on the Lithuanian composer and painter M. K. Čiurlionis (1875-1911) originally was prepared for a European contest, in which not only the artist's name, but also the very existence of Lithuania were practically unknown. Initially, this represented a handicap, for it was quite difficult to find dependable information and reproductions of his artistic work. It was only after a trip to Lithuania in March and April of 1986 and with the help of many Lithuanians that l could solve some important problems. But on the one hand, not being a Lithuanian made it possible for me to work with a totally fresh approach without feelings that may sometimes have a negative influence on research and studies.1

In considering Čiurlionis' biography and bibliography in life and post mortem, we could say that he was, in a certain sense, a victim of his genius. In fact, his productions presented many peculiarities which definitely kept him at a distance from his art contemporaries. Most likely overwhelmed by schizophrenia (1910-1911), he lost forever the chance to have his solitary art become known in Munich at the second exhibition of the Neuekuenstlervereinigung in 1910, under the invitation of Kandinskij. Similarly, in 1911 his friends and admirers in St. Petersburg departed without him for Paris to reap international successes with the Ballets Russes. If we add the wars (that notable Eurocentrism which characterizes us) and the well-known Soviet reluctance to welcome scholars to their country, together with the inconvenient location (in Kaunas, Lithuania) of practically all of Čiurlionis' works, it will not be surprising to see that his art - so disinclined to "-ism" - practically slipped into obscurity outside the 65,200 square kilometers of his troubled native land. We can now really understand why the bibliographic circumstances of this artist have for the most part been based on rapid, second-hand quotations and why they are prevalently invalidated by errors in dates, names, titles of paintings, etc.

Yet Konstantinas Čiurlionis knew how to arouse, with his art being equally distant from intellectualism and from false naivetes, interest and enthusiasm from artists such as Bakst, Benois, Diaghilev, Dobuzinskij, Lipchitz, Stravinskij (who bought a lost painting from the Pyramid Sonata) and Kandinskij (although Nina, his widow, always denied it). Art historians including B. Berenson, R. Rolland, M. Calvesi, G. Dorfles, and E. Lucie-Smith were also interested in Čiurlionis.

Čiurlionis' education began with piano and composition studies in Druskininkiai, afterwards in Plungė (1888/89-1893), Warsaw (1894-1899) and finally in Leipzig (1901-1902). He was already a mature composer and piano soloist when he started taking drawing lessons in Warsaw (1902-1904) from Kauzic and perhaps from Kryzanowsky. In 1904, he enrolled m the newly founded Art School where Ruszczyc and Stabrowsky (or Stabrauskas) were to be his teachers.

Another important phase of his artistic formation was his trip to the art galleries in Central Europe, to Prague, Dresden, Nueremberg, Munich and Wien, in 1906. As we note, it was mainly the German world that attracted Čiurlionis more than French impressionism or Italian painting. The turning point in his life is to be seen between 1905 and 1906 when he decided to dedicate all of his art to his native country. In this very period, Konstantinas became a full-time painter and left the music that was his primary occupation.

What were the reasons? Several authors have written that it was probably the disappointment he had in the field of music which led him to this decision. But it seems to be a rather weak argument. If, however, we consider that from 1905 on Konstantinas (who had mainly lived in Warsaw and usually introduced himself as Polish) began to exalt his own Lithuanian culture and history, that he helped organize the first two exhibitions of Lithuanian art (1906 and 1908) and that, above all, he began to study Lithuanian (and the teacher, Sofija Kymantaitė, was to become his wife in 1909), we can understand that only with painting could he embody and express his patriotic sentiments, while with music he would probably have remained linked (as he in fact was, with his atonal and almost dodecaphonic anticipations) to Western compositional outlines. Only painting could reach the peasant population (and, at the time, "peasant" was a synonym for a real Lithuanian national), which was far from "elitist" intellectualisms.

M. K. Čiurlionis, Pavasario sonata, Allegro, 1907 (Sonata of Spring,

Allegro, 1907)

M. K. Čiurlionis, Pavasario sonata, Andante, 1907 (Sonata of Spring,

Andante, 1907)

The span of his painting production goes from 1903 to 1909, which is a very short time to discuss actual periods. However, four phases can be identified in Čiurlionis' progressive artistic maturation. The 1903-1904 phase was somewhat linked to a generic symbolism with a rough paintbrush and a vivid chromatism. In the 1905-1906 phase, an "adjustment in attempt" is noted, with a greater insistence on what were to be his favorite themes (the cosmos, the seasons, etc.). The 1907-1908 phase, probably his best period, was characterized by musical titles and with subjects taken from popular art. The color is more refined now and the forms more precise. Finally, 1909 seems to have marked a sort of creative state with regards to subjects: possibly many suggestions of his mental instability can be found in this period.

In interpreting the work of Čiurlionis, we must take into account the various "components, cultural and other, which were significant in his life and his artistic productions. His interests included music, the pictorial environment of Romanticism in Warsaw that expressed itself by means of landscape painting, and by interposed, continuous and wide reading (from Poe to Dostoevskij, from Tagore to Mieckiewicz, Wilde, Nietsche, Ruskin, and Indian legends). They included astronomy, psychology (in Leipzig he followed W. Wundt's lessons on experimental psychology), and the religions of ancient Egypt, and cabalistic and Indian philosophy. National political ideas also had an important role, as in the end did his own mental illness.

M. K. Čiurlionis, Pavasario sonata, Scherzo, 1907 (Sonata of Spring,

Scherzo, 1907)

It is possible to insist on the various components in Čiurlionis' art because in all these years the artist has been classified, with only a few exceptions, as a "musicalist-painter" who achieved a sort of synthesis of arts and as one of the first abstract artists.2 There are about 30 musical titles in Čiurlionis' paintings (7 sonatas, various preludes, fugues and fantasias) and musical theory could have had an important influence. Certainly, paintings such as Fuga (1907-1908) and Fantazija, Triptikas (1908) may suggest counterpoint, and we seem to be allowed to compare the painted sonatas with the musical ones. In music, for instance, we may have three or four part sonatas. In Čiurlionis' paintings, the second movement may be a fairly slow Andante, often based on one main theme plus variations. In Čiurlionis' Andante, we notice one principal motif (as a mill in Pavasario Sonata, 1907; the snake in Žalčio Sonata, 1908; the tree in Vasaros Sonata, 1908.) Čiurlionis' Scherzo generally shows a rich series of interwoven motifs that could resemble the musical Scherzo, the rhythmic second of a sonata. And lastly we can also admit that Saulės Sonata (1907), with the frenzied bell in the Finale where all the motifs of the other sections of the cycle are repeated, owed much to the late Romantic Ciclic - Sonata (e.g. of F. Liszt or C. Frank).

However, this is not the correct approach: Čiurlionis never showed much interest in giving precise explanations to his works. We must notice that whoever has tried to achieve a "Synthesis of the arts" (Ph. O. Runge or A. Skjabin, just to mention two) has done it in very few works, preceded by meditations, writings, and with a suffered, slow gestations, which has nothing to do with Konstantinas' creative impetus and speed of execution. Čiurlionis painted in tempera, a technique which does not admit all those doubts and second thoughts that characterize synesthetic processes.

In the various sonatas, we must look for other meanings. More than musicalism, the use of natural elements (e.g. of sun - Saulės Sonata - or wind - Pavasario Sonata), the interest in popular elements, the artistic research (e.g. bidimensionalism against three-dimensional representation) and the link with mysterious theories (e.g. Žalčio Sonata or Piramidžių Sonata) were included.

M. K. Čiurlionis, Pavasario sonata, Finale, 1907 (Sonata of Spring, Finale,

1907)

Why then the references to music? l think that the answer is in a topos of the period to characterize in this way the departure from references to natural information. For this reason, Whistler entitled his paintings with the most "abstract" intentions, Harmony and Symphony; De Wizew (1886) called 0. Redon, the "peintre synphonique," opposing his art to that of some impressionist, which, in his opinion, was too "material." Kandinskij was to write many pages on the relationship between music and paintings, leaning towards an expression of interior reality. Nevertheless not one of them, nor much less the arabesqued graces of Klimt or the coloristic counterpoints of Klee (a good violinist, among other things) or even the musical paintings of Kupka '(who was linked to Theosophy, occultism and himself a medium), where the subjects of synthetic lucubrations on the part of critics or scholars.

Čiurlionis as an abstract painter? It would take too long to glance through the path towards abstraction, starting from ink-blot composition by Alexander Cozens (1717-1786), passing by C. Friedrich and Ph. 0. Runge (who considered their paintings as abstract), the xylographies of Van de Velde (1893), the panel by A. Endell (1896), the works by Kubin in 1906 and those by Macke in 1907.

There is no work by Čiurlionis that can be considered as abstract; the artist's horizon remained always that of our world in connection with the superior one of gods and angels. In this perspective he is more linked to the art of romantics (e.g. C. Friedrich) than to symbolism. Čiurlionis' work had no morbid or disturbing aim found in symbolism, and works like Vasara I and Vasara II (1907-08), two of the greatest heights reached by the artist, prove the distance that exists between the Lithuanian and many other painters of his period.

But now, after having said what Čiurlionis was not, let us attempt to identify positively his artistic journey and to interpret his production which, one recalls, originated within the sphere of the Polish world of Warsaw.

Above all, several affinities with Polish authors of the era, or of the slightly earlier era, can be revealed. The initial use of pastels and fluor etchings is referred to the example of S. Wyspiansky (1869-1907). The habit of combining the paintings into cycles can be recognized in A. Groettger (1837-1867), from whom one can derive a macabre cue as that in Laidotuvių Sinfonija III. In J. Malczewsky, we notice a similar use of figures taken from popular imagination and ancient mythology, as well as the choice on the part of W. Wojstkiewicz (1880-1909) of subjects inspired by the world of fables. All these elements are present in a distinct manner in Čiurlionis' productions, although always elaborated with extreme personality.

M. K. Čiurlionis, Saulės sonata, Andante, 1907 (Sonata of the Sun,

Andante, 1907)

M. K. Čiurlionis, Saulės sonata, Scherzo, 1907 (Sonata of the Sun,

Scherzo, 1907)

However, with regards to iconographical and compositional choices, we look mostly elsewhere, beginning with his teacher Rusczozyc, who was almost quoted to the letter in Taurus, and in the cycle Winter. Similarities can be noticed between E. Munch's woods and Čiurlionis' Miško Muzika (1903) and Miškas or between A. Boecklin's Isle of the Dead and Tvirtovė or Vakaras (1904 ca.). While in Laidotuvių Sinfonija (1903), we notice the iconography of the male enshrouded in cloaks and seen from the back, that will play a large part also in De Chirico. Something similar could be found of the dreaming art of V. Borrisov-Mussatov in Rytmetis l and Rytmetis II (1903-1905). O. Redon and Puvis de Chavannes are recognizable in several component cuts, especially in the initial production and in the sketches which, as they are abounding in ideas which were not used in paintings, would be worth a study on their own. Fairly interesting are the affinities with the Czechoslovakian world of Panuška (1872-1958), as in Diena and Vakaras (1904ca.),or of Hlavaček (1874-1898), see Mintis (1904 ca.) and, in the last three years, in Japanese art (waves, bending trees, archipelagos, temple doors, etc.) and Art Noveau (Spring Sonata, Star Sonata, ink and folk song drawings, initials).

M. K. Čiurlionis, Laidotuvių simfonija I, 1903 (Funeral Symphony I,

1903)

M. K. Čiurlionis, Laidotuvių simfonija II, 1903 (Funeral Symphony II,

1903)

This all demonstrates that although he lived in a remote province of the Russian Empire, the artist was informed on the principal ferments of Europe. In fact, Warsaw was in close contact with St. Petersburg, the city where the Mir Isskustva group organized several exhibitions of West European art. But various contacts also existed with Krakow3 which were particularly linked to Munich and Wien. Nevertheless, these iconographic examples were subjugated by the Lithuanian artist's sensitivity in an absolutely personal and unique manner, free from the initial suggestions of the contemporary artistic production. In order to easily understand this, it is enough to observe the absence of the human figure, an absence which is balanced with the shifting of the painter's attention towards the superhuman. This change of perspective (similar to C. Friedrich) was expressed in a most explicit manner by means of the portrayal of powerful supernatural figures such as Rex, (the king) surrounded by planets, stars and angelic throngs singing hosannas or of gigantic figures made of clouds and shadows (Mintis, the cycle Night and Day, etc.). Directly connected is the insistence on the cycles of nature, victor over the ephemeral man, and iconography regarding the cosmos.

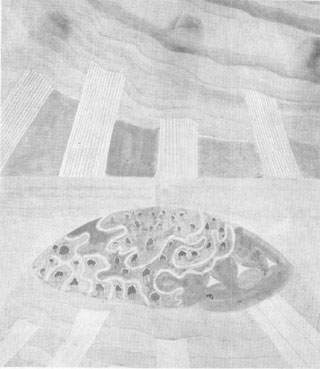

However, of the greatest importance is the constant use of an "ascending" symbology which alludes to the transit from an inferior reality to a superior one. The angel, bird, snake, bridge, stairs, rainbow, pyramids, mountains, pylons, and arrows represent a further amplification of the idea of elevation. Note the presence of a sacral symbology, altars on which a fire burns (the sacred fire of offering, Aukuras, 1909, and Žalčio Sonata; finale, 1908), the angel which makes its offering nearby (Auka, 1909) or other mysterious signs including a genuine initiatory cryptowriting present in important places such as thrones, pylons, and altars. These allude to a higher type of communication.4

M. K. Čiurlionis, Aukuras, 1909 (The Altar, 1909)

A question may now arise. Must Čiurlionis' iconographic choice be simply considered as a matter of personal style (as Cubism for Picasso, Futurism for Boccioni, etc.) or is it to be linked to some other, deeper roots? The essays of M. Eliade, G. Durand, and R. Guenon assure us that every symbol that we have seen in the artist's production can also be found with analogous meanings in the most disparate regions of the world during the entire course of history. This implores us to try to give a better interpretation to the art of Čiurlionis.

What was M.K. Čiurlionis expressing through such symbology? We can give a double answer to this question - one concerning what the artist wrote and said and one matched to his psychology. Čiurlionis intended to speak to the heart of peasants that were the bearers of the true Lithuanian culture and wanted to develop national art and music. For this reason, he always refused to explain his paintings, hoping that the peasants would give a personal meaning and explanation to them. There are many evidences of such attempts.

But in a less rational way, we must remember that Konstantinas' life seems to have been characterized by an ever latent anguish, a state of insecurity, and mental stress which found expression in continual travels, readings, studies in the most varied fields of knowledge, occultistic interests, and the obsessive return to the same thematics not only in painting, but also in music. The progress of the disease can then be followed in iconographic and compositional details such as serialization, schematism, bidimensionality, circularity, the process of enlargement of forms and figures, and in the insistence on themes and settings from fables. We can have an idea of this in the decoarted vignettes for folk songs (1908) where a phitomorphic decoration -"compulsively filled with the small circles which sometimes occur in the work of mentally deranged" (Hamilton' - submerges the actual musical score. In a painting like Aukuras (1909) with the upsetting disproportion between the Zigurrat-altar and the most invisible ships below, in the serialism of Rex (1909), with a universe reduced to mechanized fixity in which reflection and repetition are connected in an indubitably magnificent synthesis (but one without a way out) the consonance with the art of a Swiss schizophrenic A. Woelfli here take on tragic evidence.5

M. K. Čiurlionis, Rex, 1909

Lastly we can connect Čiurlionis' obsession with the idea of living in the period of the consummation of the times with some phrases taken from G. Durand. Durand states that "vegetal symbolism is always linked with every mediation of duration and of aging, "that fire" is the symbol par excellence of total destruction and of total regeneration," and that the snake and the Uroboro "are the symbols of temporal transformation and the custodians to be feared of the ultimate "mystery of time: death." This is enough to understand that the artist expressed in his art a typical problem of our era, namely the anguish of being faced with time and the attempt to win human decadence.

These words do not undermine in any way the genius of Čiurlionis. It is enough to think that Theosophy and Mysteric theories have been proved to be the main components in the change of Kandinskij from the delicate symbolist to the so-called abstract painter we all know,6 that Van Gogh, Nietsche, and Hoelderlin, suffered of mental problems and they all are considered fathers of modern culture and real interpreters of our age.

M. K. Čiurlionis, Žvaigždių sonata, Allegro, 1908 (Sonata of the

Stars, Allegro, 1908)

I wish to give an answer to the problem of the various occult contacts which definitely existed, bearing in mind that Čiurlionis lived in the golden period of Theosophy and spiritualism. However, we are not able to define either when or at what level of the period because many sources deny or minimize the question for fear that these occult "weaknessess" could undermine the artistic genius of the painter, while letters of memories have been published ad usum Delphini. A. Rannit7 tells us about a letter that the artist wrote in 1909 to the Theosophic Movement in St. Petersburg in which the painter "rejects any relationship to any modern religious or philosophical theories and dogmas in his work." Yet, the very evident connection between Žalčio Sonata and "das Maerchen," a Masonic fairy tale by Goethe that was theosophically reinterpreted by R. Steiner in 1899 and 1918 cannot be hidden. In Piramidžių Sonata there is a very clear initiatic meaning. In the Žvaigždžių Sonata a meaningful vision of (probably) chaos or universe and the presence of mysterious elements such as altars, cryptowriting, columns, illuminated grottos, and sea travels may suggest that Čiurlionis could have been acquainted with Masonic environments.

After being locked away in Pustelnik near Warsaw in February 1910, on occasion Čiurlionis was allowed to play the piano and to draw, but almost nothing seems to have survived. In November 1910, the artist sent a postcard to his wife and his daugher, Danutė Sofija, in which he wrote that he was hoping to come back home soon. But, a cold, which degenerated into pneumonia caused his premature death on 28 March 1911 (old calendar).

How can we conclude this discourse on this great Lithuanian? Perhaps by expressing the hope that the art of this unfortunate musician and painter will be recognized in the proper manner, although we cannot entertain promising expectations. Čiurlionis' works were executed on second rate pastels or tempera on cardboard due to his chronic poverty. Thus the curators of the Čiurlionis Museum in Kaunas have reasonable hesitation to lend out paintings. On the other hand, almost all the paintings are in Lithuania; the fact does not encourage artistic research.

Given the situation, we can understand that Čiurlionis' work cannot be subject to commercial launching. We must wait, hoping that eventually political barriers one day will fall apart and cultural interchanges will spread everywhere.

* Andrea Botto studied at the Conservatorio di Musica S. Cecilia in Rome and took his diploma in Classical Guitar in 1959. He continued his studies in music and art at the First University La Sapienza in Rome, graduating summa cum laude in Contemporary Art with a thesis on M.K. Čiurlionis. He is active in the musical field (concerts, records, teaching) and in art history. He collaborates with the State Fine Arts Department (Soprintendenza ai Beni Artistici e Storici) in Florence researching still-life paintings with musical instruments at the Uffizi Gallery.

1 Concerning this important problem, I'd wish to quote the interesting incipit of an article by Dr. K. P. Žukas {Čiurlionio dailėtyros klausimais, in "Metmenys" 1975, #30, p. 119) that points out a negative way of thinking of celebrations and studies: "Nesunku atspėti, kad M. K. Čiurlionis gimimo šimtmečio proga vyks apsčiai jubiliejinių minėjimų ir akademijų, nuo kurių tribūnų sklis drąsios panegyrikos, sacharininės paskaitos, proginiai eilėraščiai, skatinimai dailininkam pamokos liaudžiai ir t.t. Šventėm praėjus, tikėkim, šitokios tuštybės bus užmirštos, lyg tų minėjimų iš viso nebūtų buvę."

2 E. g. Gabriella Di Milia, in "Cahier du Centre Pompidou" n.3, 1980 or in "F. M.R." n. 18, 1983. Also the thesis "The Work of M. K. Čiurlionis in relation to his period" by M. Nasvytis, Case Western University 1972, is to be considered a fundamental source because it mainly studies the other cultural elements in the artist's formation.

3 We can cite the two reviews Zičie in Krakow, and Chimera 'in Warsaw; in each of them artists of both cities worked together.

4 R. Guenon points out the fact that angels and birds in various popular legends are said to speak with a cryptic language that can be understood only by initiation - see "Symboles fondamentaux de la science sacree," Paris 1962. About ascentional symbols and symbology in general see G. Durand "Strutture antropologiche dell'immaginario" Dedalo 1982. Čiurlionis also invented a personal cryptic-alphabet - see "Apie Dailę ir Muzika" p. 179.

5 About pathological connections between reality and its double (reflection/shade) see 0. Rank "der Doppelgaenger." For the art of schizophrenics see C. Bollea, in "Art e Dossier," n. 10,1987 and in the catalogue of the exhibition "Debuffet e l'Art Brut" Venice 1987.

6 To get acquainted with the problem see S. Ringbom, "The sounding cosmos" Acta Academiae Aboensis Ser. A. Humaniora, vol. 38 n. 2, Abo 1970.

7 This letter is mentioned in Lituanus, VII, 1961, p. 44 Note 8. As far as occultism is concerned, C. Belloli writes that Čiurlionis followed in Warsaw (1905) the "Knights of Christian of Rosenkreutz; in this town he joins Masonry and he will achieve the 30th degree (Kadosh,)" in "Contributo Russo alle avanguardie plastiche," Galleria il Levante, Milano-Roma 1964. It cannot be judged if this is absolutely true for Belloli in other points makes several mistakes writing about Čiurlionis' life and production.