Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas, University of Rochester

Copyright © 1990 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 36, No.3 -

Fall 1990

Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas, University of Rochester ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1990 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

JURGIS ŠAPKUS

ALGIMANTAS KEZYS

Jurgis Šapkus is a contemporary Lithuanian painter and sculptor in Southern California. He was born in Lithuania, and came to the United States in 1952. He studied art at the Ecole des Arts et Métiers in Freiburg, at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich, Germany, and later at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago.

When developing his style, he was inspired by the Expressionist painter Max Beckman, by sculptors Barlach and Lembruck of Germany, as well as by the Lithuanian-born sculptor Jacques Lipshitz. He also admires the American painter Ricco Lebrun.

He has traveled extensively throughout Europe, Asia, and Mexico, where he has sculpted and painted. He has participated in many national and international exhibitions and has been featured in the National Sculpture Review. (Fall 1982).

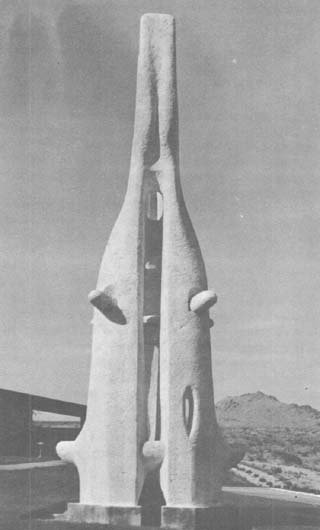

His sculptures have been exhibited in the North American Sculpture Exhibition at the Foothill Art Center in Golden, Colorado. His water colors and oils were shown in Stuttgart, Germany, the Riverside Museum in New York City, and in Willistead Gallery in Windsor, Canada. Commissions have included a nine-foot figure of "Christ in Sorrow" and two six-foot figures of "Florian and St. Izidor" for the Holy Cross Church in Chicago; a series of sculpted wire figures and stained glass murals for the Chicago Savings and Loan Association; and a 24-foot "Gemini" fountain, of cast stone, for St. Mary's Hospital in Apple Valley, California.

While working with stained glass during a six-year period, he designed and executed a complete set of windows for St. Donatus Church in Elmhurst, Illinois; two altar windows for the Polish National Church in Chicago; and windows for various churches and temples in the Chicago area.

Also a set designer, Šapkus designed three stage sets for the musical "Eglė, Queen of Serpents" for the Alice Stephens choral group at the Chicago Ashland Theater; two stage sets for the comedy "The Mistaken Account"; a backdrop for the ballet "People of the Sun"; and two stage sets for the children's play "The Beckers Boy."

Šapkus' work is expressive and spontaneous, full of energy and courage. Through bright colors and uncompromising forms, he communicates a direct, honest, and inspiring interpretation of life. In his early years, he struggled to survive and went through many stages painting murals, designing stained glass, and carving architectural sculptures. For several years, he produced stage settings and has even designed toys. In the toy industry, he is known as an inventor and a concept designer. He has more than 20 patents to his name. Today, he dedicates most of his time to alabaster carving and watercolor painting.

"The qualities I most appreciate in art work," says Šapkus, "are spontaneity, strong movement, and a deeply-felt concept. I get enthusiastic about a master's free-handed drawing and loose-brushed strokes, no matter in what style the art is."

"Gemini", Fountain, 1966, cast stone, 24 feet high. Apple Valley, California.

Human figures are the main subjects in his sculptures: "I love people. Working on the art piece and forming it until it is in harmony with my feelings is my goal. I do not ponder about 'Weltschmerz' (sentimental pessimism) or 'Angst' (neurotic anxiety). If the work is honest, it must be in harmony with the 'Zeitgeist' (spirit of the age). I have a feel for what I want to express, and when I am finished, I know if I have expressed what I intended."

Recently, Šapkus' art shifted direction. He turned from universal ideas to ethnic subjects. First he found inspiration in Mexican art and then he turned to his native Lithuanian folk art. While traveling through Mexico, he sketched and sculpted from Mexican models. He stayed in San Miguel de Allende for a long time. The people of this area have strong facial features; their lives appear inscribed in them. Šapkus became fascinated by them and by their environment. He also studied the collection of photographs from the Mexican War of Independence, some of which can be viewed on the walls of Mexican restaurants in the United States. These photographs portray people of races and classesIndians, Spaniards, rugged peasants, students, intellectualsdressed in their own interpretations of military garb. They posed for the camera with an awareness of their individuality and the great importance of their roles.

"These pictures," says Šapkus, "appeared to express the essence of the people's universal struggle for their destiny and dignity. This struggle sometimes takes the form of violence, and this violence becomes acceptable and respectable because of the ideals it is supposed to realize."

These were the thoughts in Šapkus' mind when he was preparing himself for artistic expression. Then he met a Mexican-American artist, whose father was one of the generals in those photographs. With great anticipation, he explained his ideas to her. It turned out that she not only had similar thoughts, but she had painted them on canvas.

"These paintings were not as I would have done them," admits Šapkus. "But the knowledge that somebody else had tried took me aback. Suddenly I felt like an outsider intruding in what was none of my business. After this sobering experience, I opened the books on Lithuanian folk art."

The book that Šapkus opened was Lietuvių liaudies menas (Lithuanian Folk Art) by Paulius Galaunė. In this book, Galaunė reproduced old graphics of icons as samples of genuine Lithuanian folk art. These were primitive drawings by anonymous artists who probably never thought of being incorporated into the scholarly books of Lithuanian art history. Šapkus says he felt drawn to them: "My copy of Galaunė's book on Lithuanian folk art is old and torn. The black ink is smudged. The pictures reveal love for the saints and other religious subjects. The art is primitive, strange, and at times, downright ugly. But it is touching and heart-felt. I started doing my own interpretations, changing the arrangements to my liking, adding strong colors. And it felt good. I became attracted to the simplicity of these folk artists, and I knew I was affected by their childlike devotion to God."

Inspired by the samples from Galaunė's book, Šapkus began a series of watercolors and acrylics. "St. Barbara with Chalice" shows an old anonymous Lithuanian folklore poster, promoting women's priesthood. "The Last Vaidilutė" is about a pagan priestess who guards the eternal flame. Before Lithuania was baptized in Christianity, the land was ruled by "Perkūnas", the god of thunder. Within Perkūnas' court, young maidens, called "vaidilutės" attempt to shield the eternal flame from extinction. "Vaidilutė pabėgėlė" dramatizes a "vaidilutė" who becomes a refugee.

After the advent of Christianity, the pagan guardians of the flame were exiled, but the flames, according to the artist, have never been extinguished.

"The Last Supper" is a watercolor sketch for a mural. In this scene, St. John leans on Christ, who dips bread with Judas, whose shadow is reflected on the table. St. James embraces St. Peter who is rescued from drowning. St. Andrew stands with his arms crossed, foreshadowing his form of crucifixion. Further on, St. Philip, St. Matthew, and St. Bartholomew speak among themselves worriedly, as if they have a premonition. Also shown are St. Thad, St. James, and St. Thomas, who will not trust his own eyes when he meets Christ after the Resurrection.

"The Death of a Drunkard" is an updated parody of an 18th century poster promoting abstinence. The inscription from top to bottom reads: "A peaceful death for those who abstain from drinking; Returning from the market the drunkard will be killed in an accident; The drunkard covets his neighbor's wife; The drunkard's death: the devil, the undertaker, and the lawyer toast the drunkard's death; Wife, buy this picture of abstinence for your husband; it is cheaper than a funeral."

Drawing from the richness of the folk art and being inspired by it, contemporary artists can transform it to the level of fine art. Šapkus maintains that even the work of an artist of international fame often expresses the individuality of national differences, emphasizing his country's character, lifestyle and history. Such art forms as "German Expression-ism", "French Impressionism", or "Fauves" are appreciated by all.

"In medieval times," says Šapkus, "the art of Italy had a different character than the art of Spain. In the majority of Picasso's paintings, the Spanish heritage is easily felt. The Mexican artists Orrozco and Diego Rivera are not only Mexican in style, but also deal with the political life of Mexico. The fact that an artist's heritage is reflected in his artwork is an advantage."

The dilemma arises for those artists who have been displaced from the country or their origin since childhood, or for those who have been away and had no direct contact with their country for a long time. Šapkus is one of those artists. Can he still be a true Lithuanian artist? Šapkus names some of the specific elements that characterize his art as Lithuanian:

"Lithuanian people throughout history and at the present time are steeped in pain and suffering from political oppressors. Consequently, they often turn to trust the power of nature and the graces of their creator. This gives a transcendent quality to their artistic expressions."

Because family members are lost in wars for their country's freedom, are deported to distant parts of the world, or are killed in prisons and concentration camps, the survivors seek refuge in the solace of ancient myths and religion.

"For a young orphan girl (a bride-to-be), the moon takes the role of the father and the sun replaces the beloved mother, and the stars adorn her hair," says Šapkus.

The basic relationship of life's struggle are expressed in terms of family ties and social obligations to others and to the country. Šapkus seems to believe that folk art traditions are probably the best indications of a genuine ethnicity enriching every artist's endeavors toward personal art.

"I do not imitate the old art of the Lithuanian past, nor do I copy it," says Šapkus. "I find joy in interpreting and using this visual language in my own way. It is an opening of a new window, a way to see and do things differently."

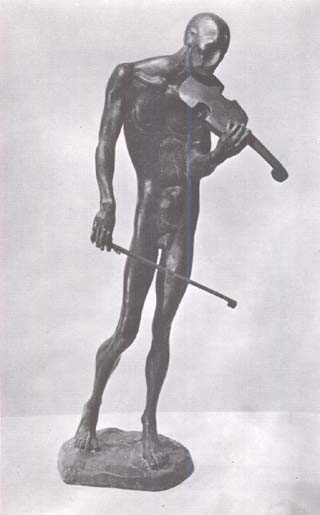

Jurgis Šapkus, "Violinist," 1979, copper 25" high, collection of Birutė Bružas, Oakland, California

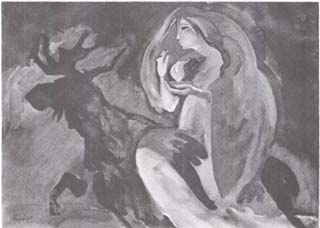

"Evening Fear", 1977, watercolor, 20"x28", collection of

Patricia Tuo Cloonan, Los Angeles.

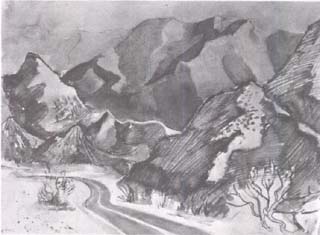

Jurgis Šapkus, "Where the Mountains Meet the Desert," 1978,

watercolor, 20"x28" collection of George Clark, Hermosa Beach, California

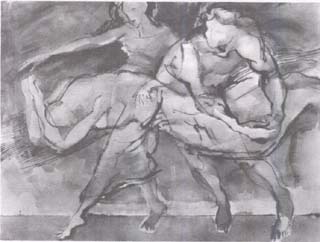

"Eurythmy of Deliverance", 1981, watercolor, collection of Vaidotė Baipsys, Costa Mesa, California.

Jurgis Šapkus, "The Mad Ashram," 1981, watercolor, 30"x22", collection of George Clark, Hermosa Beach, California

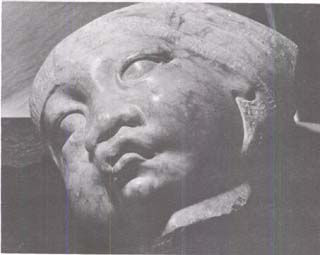

Jurgis Šapkus, "Oriental Head," 1983, California alabaster, 15"x18"

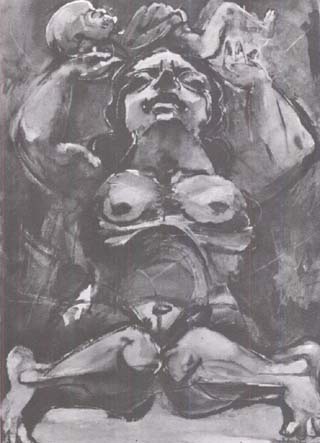

Jurgis Šapkus, "Agony of the Third World," 1981,

watercolor, 30"x22"

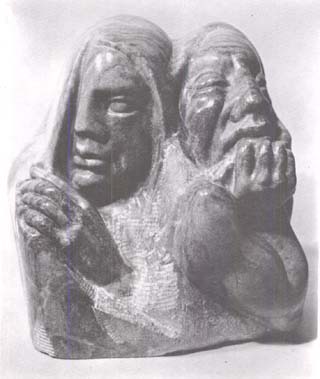

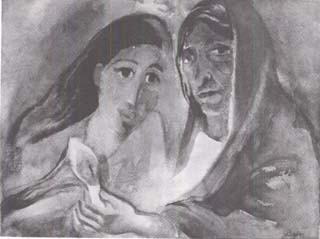

Jurgis Šapkus, "Two Generations," 1984, Utah alabaster, 14" high

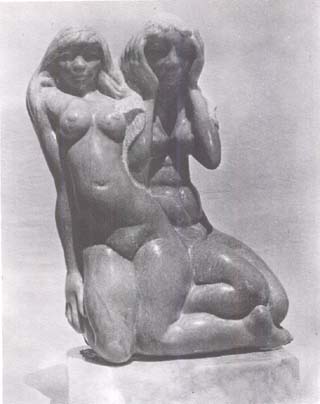

Jurgis Šapkus, "Sisters," 1984, Utah alabaster, 24" high

Jurgis Šapkus, "Metamorphosis of an Angel,"1984, Utah alabaster, 22" high

Jurgis Šapkus, "The Guardian of the Flame Becomes a Refugee," 1988

watercolor and acrylic, 22"x30"

Jurgis Šapkus, "The Night of Souls," 1988, watercolor 22"x30"

Jurgis Šapkus, "Relaxation," 1988, terra cotta, 18" high

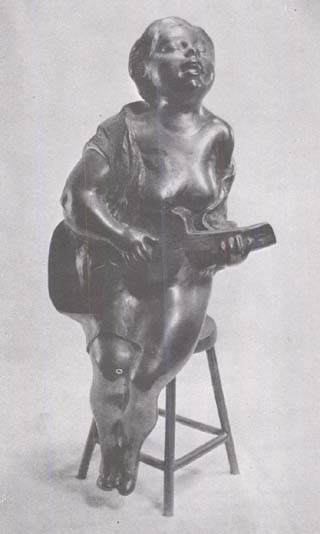

Jurgis Šapkus, "Folksinger of Mexico," 1987, bronze 22" See page 54. '