Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas, University of Rochester

Copyright © 1994 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL

OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 40,

No.3 - Fall 1994

Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas, University of Rochester

ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1994 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

LATVIAN INVESTMENT CLIMATE

GUNDAR J. KING

Pacific Lutheran University

Economic Problems and Research Approach

Critically short of capital, the Baltic states have only modestly succeeded in bringing international investments to their economies. Even then, major investors have sought unusually high profits combined with government guarantees, special privileges, and protection against competition.

Reasons for this state of affairs are not hard to find. International advisers consistently place Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania more or less on par with opportunities in Russia, ahead of the Asian republics of the former Soviet Union, and behind the countries of Central Eastern Europe. They do not have good company (former Yugoslavian states, and troubled African nations). The Baltic states share with each other low ratings of economic performance, political stability, access to international bank loans and sources of investment funding, and prospects of assistant loan repayments. Analysts who identify these problems are not generally optimistic about their solution in the near term.

The approach of this study is to focus on the Latvian investment climate as seen in mid-year 1994, combining personal observations, and assessments gathered in 1992-1994. This review does not rely on detailed yet fairly unreliable statistics to make uncertain forecasts. Rather it seeks to explain the Latvian situation in terms of strengths and weaknesses, and offers suggestions for improvement. Although the situation is, in many ways, similar in all three Baltic states, there are also important differences a thoughtful reader should consider before extending the analysis of the Latvian case to its neighbors. In any case, I believe that the main keys to investment climate improvement in the Baltics are better economic performance and improved political stability. These combined tasks are well beyond the abilities of one government or another. They are also subject to leads and lags. They call for sustained action by the leadership in all sectors of the Baltic nations, on all levels.

Sights of Transition

Latvia, a country of spectacular economic activity and growth a century ago, is now searching for a new economic and political future by combining its strong economic ties to the former Soviet Union with its expansion of Western trade.

Latvia offers growing long-term potential to the investor active in management. Although historically an agricultural country, today it has a dual character. The capital city, Riga, of nearly a million, is a Baltic city where the Russophone population is the second largest to that of St. Petersburg. It is also the largest city of Latvians. Riga, the birthplace of aviation, automotive, and electrical equipment industries in the Russian Empire, remains a gateway to Russia.

Following the collapse of Russian demand for capital equipment and military electronics, Latvians are eager to discuss ideas of how to make optimal use of the large industrial assets left in many Soviet-built factories. Following the 1993 national elections, and the unseating of the transitional Popular Front government, composed largely of former Soviet bureaucrats, there is a shift to a more western democracy. Latvian leaders are now Grafting measures that would establish an environment more favorable to international investment and that would also be acceptable to a conservative population. A Latvian Development Agency works with international investors. A Port's Council is a new factor in the improvement of port use.

This process will continue to be painful, uneven and slow. Ultimately, however, it will be profitable as business values are accepted more widely. International trade and investments will rise to underpin the country's economic growth and stability.

The first signs of progress are already apparent. There is monetary stability with conservative management at the Central Bank of Latvia. There is a small yet growing stream of Western International investors and trading partners who do business in Latvia, and there is a new American Chamber of Commerce to exchange ideas and experience. There is the graduate Riga Business School with English as the instructional language, run by the State University of New York at Buffalo. A private school with excellent Russian contacts is the Riga International College of Business and Economics. There is the new Euro-Faculty (including a branch of the Stockholm School of Economics opening in Riga in the fall of 1994) sent by the European Community to help transfer Western knowledge to the Baltics. There are economically effective and profitable Western ventures with some Latvian enterprises which set good examples and provide very useful experience. Although Latvian leaders continue to emphasize their traditional values in an effort to enhance the nation building process, they are eager to learn more about successful Western business practices.

The present Latvian government is based on a centrist coalition. Elected by citizens of Latvia in 1993, this plurality coalition is now aggressively encouraging foreign investment. The parliamentary priority agenda includes legislation to establish the constitutional framework for a democratic society, a bill of individual rights, and the systemic conditions appropriate for economic reconstruction and development. This agenda is urged, among others, by the Latvian legal community favoring international investments. The parliament itself now has a critical mass of Latvians from the West to help formulate policy. The cabinet ministers in charge of the economic and financial policies and legal systems have substantial and up-to-date western education and training. Most importantly, there is now a stronger Latvian general interest in alliances with western partners. There are plans for Free Trade zones, and there are the beginnings of an R&D park at the Riga Technical University. In addition, a massive evaluation of research that was recently completed by the Danish Research Councils is the basis for the formulation of new science policies.

Below is a review of major factors making up the investment climate in Latvia. It does not draw on often distorted statistical data. Those interested in measuring Latvian international trade and investment potential are advised to use actual physical measures where available. Counting the heavy Western passenger traffic at the Riga airport and watching ships calling on Riga's ports are two suggestions.

Keys to Stability and Growth

Latvia's economy remains turbulent as the parliament and economic ministries identify economic priorities, introduce new policies, and seek more productive relationships with the West, Russia, and other neighbors. Formulation of policies and actions taken to begin real Baltic trade cooperation already exceed the meager accomplishments of the interwar period. There is good experience for the development of joint commercial policies, and an excellent preparation for writing legislation common with the European community.

Depletion of human and other capital, continued with an inability to make successive investments in knowledge and improvements in capital resources is a major factor in delaying growth. On the other hand, investments made are critically important to the country as a whole, as well as to organizations and individuals involved.

The most encouraging factor is the monetary stability provided by the Bank of Latvia. The remarkably stable Latvian Lats readily converts to about US $1.80. As holders of dollars have converted them into Lati, the Lati have begun to replace dollars as store of value.

Still, the Lats is also subject to pressures of inflation, which is expected to rise at a rate higher than that of the United States. Public sector deficits, in the past caused by a poor tax system, and a relatively undeveloped domestic financial sector, are now limited to modest increases. Inflation rate, reduced to an annual rate of about 36 per cent. It is in part checked by an effective, although small, placement of government short term notes (25 per cent annual rate for 40 days) in the local market. There are, however, strong public sentiments favoring increased deficit spending.

Another strong inflationary factor is the pressure to raise the very low wages and incomes in Latvia. These incomes may erode further as more world prices are introduced and less subsidies are provided for products made locally. The rising costs of energy imports continue to challenge the Latvian government.

Rent controls, at a very low artificial level, are not likely to work for very long. Wages, salaries, and prices are very low in comparison with those of Latvia's trading partners. Rewards for high productivity in some companies and a strong demand for newly critical skills (computer programming and communications in English, for example) in other organizations are forcing wages up. There is a general pressure to improve.

Although government deficits are controlled in response to expectations of the International Monetary Fund and other international financial institutions, the lack of investment and accumulated losses of public and private enterprises (including farms) present a major potential destabilizing force. Government agencies and enterprises as owners of firms are unable to cover maintenance and energy costs in the large public housing sector. Tenants unable to meet rising occupancy costs are bankrupting these government agencies. As a result, sweeping privatization measures remain essential to reduce what are real and expanding budget deficits.

Because of insufficient revenues, government agencies designated to buy agricultural products, delay payments to farmers for many months. To prevent unemployment from rising, companies owned by government still continue to keep the unemployed on their deficit payrolls. There are few funds available for minor capital improvements. Moreover, many of the enterprises affected no longer have working capital reserves. By western standards, much of the economy is bankrupt. Under these circumstances, hungry and underpaid bureaucrats make allocation and control decisions by fiat, delay normal developments, and foster corruption. Fortunately, there are plans for a major reduction of bureaucracy and the provision of living wages for the officials remaining in government service.

The tax system remains based on the former Soviet tax system and customs duties. Ii requires substantial improvements to support desirable economic development. Tax collections, particularly from the private sector, where most transactions are cash sales, are poor. Moreover, tariff regulations are not systematically enforced. Both, the tax and the tariff systems are under revision. This revision will take time, as much of this work is done piecemeal, without a clear fundamental policy. Indeed, one of the basic difficulties is that the country's list of priorities is immense. As long as a broad front strategy do deal with them all is pursued, progress on any of them is necessarily limited.

Exports

The export sector promises the greatest opportunities for rewards for the full employment of Latvia's human resources and productive assets. Export activity originates from three sources as described below:

1. Russian transit trade. There is brisk container activity in the port of Riga. Shipments from Russia, in some cases processed further in Latvia, are more of a source of customs duties collected by the Latvian government than employment. Exemplified by sales of non-ferrous metals, the transit trade is very profitable. It is, however, strictly limited by the Latvian government seeking to stop local pilferage of copper and brass from railroads, power lines, and even tombstones. Transit shipments through the oil port of Ventspils are likely to increase with Russia's ability to export or import oil products. The ice-free port of Liepaja, formerly an important Russian naval base, is expected to become important for transit and other commercial trade. It may eventually connect with projected gas storage facilities at Dobele. Transit trade may eventually use more of the Latvian merchant marine (about 100 major ships), already a major source of hard currency export revenues.

2. Textiles and electronics manufacturing are industries useful in meeting established demand in the former Soviet Union. However, due to chaos in inter-republican trade practices in the former Soviet Union, Latvian manufacturing exports are low. Where exporting is dependent on Russia's ability to pay directly or indirectly for raw materials at world prices, it lacks orders from paying customers. An example is a large, well equipped knitting mill using Australian wool. As long as the Russian economy remains unsettled, this mill and many other Latvian enterprises increasingly look for new western alliances. Prospects for this business are improving with Russia granting Latvia the most favored nation status concurrently with the agreements on the Russian troop withdrawal.

New ties with the West may be more promising. Latvian negotiations with the European Community suggest that it will soon become an associate member of the community, with excellent prospects to be a regular member by the year 2000. Thus a German buyer provides a Latvian clothing factory with all materials; the Latvian factory docs work formerly done in Yugoslavia; the German company is very pleased with quality, cost performance, and delivery on schedule. Another success story is the manufacturing of shoes for an Italian company. By comparison, the large Latvian electronics industry is in a bad state after the Gulf War. Without Russian military orders and with few prospects in the West, this whole industry faces a very uncertain future. Latvian industries based on local raw materials, be it food, lumber, or cement, have to make less drastic adjustments and are able to respond to major changes more readily. These adjustments do usually require an upgrading of quality control. Thus, Latvian breweries, now striving for quality improvements under the guidance of Western experts, offer excellent export potential.

3. New and entrepreneurial projects. Here we find a growing yet inept tourist trade, joint software ventures for sophisticated programming, and embryonic technical ventures. New exports also include opera and symphony artists performing abroad, an optometry program for Italians, aviation schools for the Third World, and construction work in Russian oil fields. Many of the new technical services are not yet captured in official statistics and tax rolls.

Values and knowledge

Recent research shows that managers in Latvia, including both ethnic Latvians and Russophones, hold values strongly favoring high productivity and organizational efficiency, as well as the productive use of personal ability and skills. Contrary to the general population, they value profit maximization. Rather pragmatic, they also want to do things right, legally and technically. They tend to be conservative in their attitudes toward change, and they abhor aggressive behavior. Older managers are more closely aligned with the former Soviet system's business practices, while younger managers accept change.

The values expressed by managers are generally compatible with traditional rural values. They share notions that motives of bankers and marketing types should be distrusted, and that their incomes arc not legitimate. After 50 years in a Soviet command economy, Latvians remain opposed to what they feel are excess profits. This also may contribute to a relatively new tolerance of shoddy work and a lack of personal responsibility. However, the value of high quality and individual responsibility is represented today in the arts, sports, and selected smaller business enterprises.

The educational system in Latvia is undergoing a gradual change. It seeks to maintain a traditional strength in natural sciences and mathematics. In comparison, humanities and social sciences are still weak. There is excellent work done in the technical trade colleges, but universities reflect a Soviet emphasis on preparation for particular work assignments and technologies. By western standards, there is too much training and not enough education. Production is favored over other business functions. The industrial skills needed are there.

The finance and marketing functions, traditionally associated with urban German and Jewish segments of the population, need to be strengthened and developed. Because these skilled ethnic components of the Latvian economy are missing, new contacts with the West must be forged.

Basic education, heavily oriented to natural sciences and mathematics, is a broad base for advanced studies. With this base, new schools, programs, and short courses abound to meet the needs of a modern society. They are, however, oriented to short term results and technical skills. Real knowledge improvement will take time with what are considered to be very scarce resources.

Essential management resources.

Most managers in Latvia are top-down administrators most familiar with Soviet systems. They are engineers or bureaucrats; they believe themselves to be good and rational production managers. Their usual perception of needed improvements is a wholesale upgrading of technology used. Their usual complaint is that someone else does not provide them with the right materials and the right time. Accustomed to their limited functions, they have little knowledge of Western management processes, accounting, finance, and marketing. Understanding of modern international marketing needs improvement. Combined with usually passive managerial behavior and lack of funds, there is little effective marketing of Latvian products and capabilities.

To accelerate the transition to a market economy, managers in Latvia need education, examples, and experience. Rather than proceed in a lock-step, linear fashion, there is an urgency to provide all three at once. Joint ventures would allow Latvian and western partners to gain from mutually beneficial learning. More importantly, it permits the alliances involved to contribute important skills combined with well placed investments to finance production and build marketing programs. In a sense, it suggests the joint use of managerial comparative advantage to do what the Latvians cannot accomplish quickly on their own. This combination is critical to the development of Latvian exports. The export sector promises the greatest opportunities for rewards for the full employment of Latvia's human resources and productive assets. As a result, the trade sector requires only modest investments.

For full benefits, the Western partner must be relatively rich in international management and marketing resources. In some cases, this investor also needs to provide working capital to the financially exhausted partners in Latvia.

Political issues.

The achievements of the former Popular Front government (formed during the disintegration of the Soviet Union) show that a populist movement can bring about a measure of political independence. However, its recent loss of popular support also shows that it is not easy to adapt a centralized bureaucratic society to the use of western political institutions, strategies, and processes.

The election in 1993 of the current government by the citizens of Latvia suggested that they were ready for major changes in government policy and practice. The new centrist government draws its strengths from about half of the electorate. It has a strong Western orientation; the coalition includes leaders from the West, eager to attract Western alliances and investment partners. In practice, the centrist government is less stable than expected. Even though it has good popular backing, it has not succeeded in making progress fast enough to meet public expectations. It is not popular. It has, however, managed to negotiate important treaties for the withdrawal of Russian armed forces in Latvia. Recently, it has shown an increasingly clearer perception of those economic policies which need increased attention, including a better use of trading opportunities with Russia and the West.

Lacking voter support, communists, socialists, and ethnic minorities are no longer fully represented in the parliament. They remain, however, close to a large block of former Soviet citizens from Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine brought to Latvia as members of the former Soviet military forces, bureaucracy, and workers. Some of these migrants and settlers are returning to their native lands. Others, joining longterm minority residents of Latvia, hope to become part of an integrated Latvian society. The bulk of the rest, including older business managers, are simply stranded in Latvia. As long as Russia is unable to provide them with the materials and markets necessary to sustain their employment in Latvia, their power and influence is limited. To the extent that these residents are able to use their contacts and connections to maintain ties in the former Soviet Union, they represent an important force for East-West cooperation.

The main support Russia can provide for this block of non-Latvians is not the presumably protective occupation force in Latvia, but trade inducements or sanctions Russia can bring to bear. Consequently, Russia remains an enigmatic factor in Latvia's international relations. Should Russia elect to participate in international trade under Latvian auspices, it will be a very important player. If it does not, it abandons what may be considered Russian loyalists to unemployment and poverty. Continuing occupation of Latvia is probably the most negative option available to Russia. It restricts Russian trade to limited-capacity Russian and Ukrainian ports and blocks better economic and political relations. Thus, the reluctant withdrawal, to be essentially completed by the end of the summer of 1994, promises to be an important favorable development, especially as it relates to the improvement of East-West trade.

Still, other difficult issues remain to be negotiated. A mutual agreement to extend the "most favored nation's" status to each other on June 1, 1994, is likely to increase flagging Russo-Latvian trade. In this situation the increased shipments of parts and subassemblies is to restore previously integrated relationships. It is expected that transit trade through Latvian ports and other transportation systems would also increase with the normalization of relationships between the countries.

Continuing Latvian-Russian negotiations are expected to be long and acrimonious. Unfortunately, this will also be a block to the quick privatization or joint use of properties claimed by Russia. The results depend on Russian perceptions of the importance of benefits related to the improved relations. They, in turn, also depend on political developments in Russia.

Nevertheless, Latvia needs international investment. Carefully planned, thoughtfully limited, and aggressively implemented, such investment holds a number of attractions. The climate for international investment has substantially improved since the election of the centrist government in 1993. The potential investor should look to Latvia for long-term opportunities.

Although Latvia offers limited opportunities for those interested in the potential of the Latvian internal market proper, it does offer opportunities in its ties to larger markets to the East. With an impoverished population of about 2.5 million it is not attractive. The common Baltic market, now under development, offers more desirable opportunities.

Until laws of property and legal status of agencies become enforceable, major capital and even joint real estate investments remain risky. The centrist government, sympathetic to foreign investment, is also aware of opposition on both the extreme right and left of the political spectrum to unrestricted control of land and major capital assets by private investors. Consequently, international investors interested in joint ventures with major Latvian firms holding real estate and major capital assets should plan to conduct comprehensive negotiations to minimize risks and misunderstandings. Because the Latvian state continues to be a very major player in the economy, any concessions and guarantees should be explicitly approved by the highest government authorities and ratified by the parliament.

Investment opportunities

Contract manufacturing, technical service and repair center operation, and trade and transport facilitation. Here, strong potential opportunities in Latvia are evident. They focus on trade with Russia and other neighboring countries, as well as with members of the European Community. Transit trade opportunities increase with the normalization of Russo-Latvian affairs. In almost all cases, a serious review suggests Latvian alliances with major Western partners can provide management, finance, and marketing to production-oriented firms willing to learn. Ventures using Latvian raw materials, physical facilities and human resources are more likely to have strong support of the Latvian government. In some plants, minor technological improvements of low cost can bring about major improvements.

They would allow Latvian industries to meet Western quality and productivity standards. Generally, contracted services or contract manufacturing with materials supplied by the Western partner can be put in place more quickly, for more immediate results.

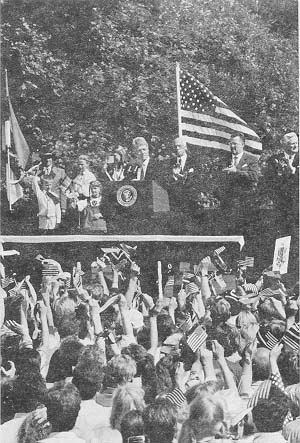

President Clinton addresses the public at Freedom Monument in Riga, Latvia on July 6, 1994.

To the right of president Clinton, the presidents: Meri of Estonia, Ulmanis of Latvia and Brazauskas of Lithuania.