Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas, University of Illinois at Chicago

Copyright © 1995 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 41,

No.3 - Fall 1995

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas, University of Illinois at Chicago ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1995 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

VINCAS KISARAUSKAS' ARROW IS STILL IN FLIGHT

MARCELIJUS MARTINAITIS

Vilnius University

Many times I hear people say that Vincas Kisarauskas was a solitary man. It may be true in view of his creative work. He coded his works skillfully. Any follower, lender or borrower of his motifs and color combinations would be spotted immediately. There is nothing that kitsch or salon art can borrow from him.

He did not enter the realm of art alone but together with a company of artists young then or, to put it more precisely, a generation who caused a real revolution at the turn of the 1960s and 70s. Such a powerful stream of artists who swept away academic painting and official art and who had an influence on other fields of art, does not seem to have occurred ever again. Kisarauskas is one of the most remarkable artists of this group and, in my opinion, he always belonged to the same generation, even when the majority left or started "producing" art. He escaped the greatest evil facing any artist stagnation, when one's own achievements are multiplied, when one repeats what is already recognized and accepted by exhibition halls, discussed in articles or reviews. Having sensed the danger of reconciliation or accommodation, he mercilessly destroyed or painted anew, scrubbed off or primed the other side of the painting.

It was most important for him to execute a work, to achieve it according to his principles, convictions, taste. That is why Vincas' art remained untouched by the political conjuncture, official, artistic or domestic, and finally, by creative dogmas, group convictions, all sorts of theories, the fleeting sympathies of critics and audience.

Kisarauskas was not fond of his works executed on commission, though it was difficult to discern in them any concessions or betrayal of principles. One could see that he was not easily fettered; he did not fit into any molds, schools, commissions, trends, companies or teams. One could discern his categorical, conscious choices everywhere. Although little was written about his creative work, his personality and his being itself was enough to encourage others not to compromise.

* * *

Creative sources are usually searched for in the artist's childhood, his family and school. There were a lot of them beautiful and interesting which arose in the Baisogala plains. Something was going on there, some kind of fermentation; it is also revealed in the poetry of Vytautas Bložė, another native of those places, whose poetry is also strange, constructed out of huge blocks. In the first post-war years, Vincas went to a school, which was part of the Komaras estate. He described his adolescent years as "singing and droning with torrents of spring, full of premonitions, anticipation, the smell of distant, promised lands". They were village children, "miserable, walking on foot for six or more kilometers" in those hard times "amidst shooting and blood, corpses and fear", as he writes in the article devoted to his teacher Povilas Krivaitis who gave "the essentials of art" to poor village kids and continued to teach Vincas after he was admitted to the Telšiai School of Applied Art.

His secondary school teacher praised his essays and predicted a great future as a writer for him. Perhaps recalling those essays and his first poems, the painter wrote in answer to a questionnaire, "Upon looking back into the past, when everything is very far, I am glad that I did not become a writer; I can feel that only in art can I express myself completely, abandon myself to it fanatically, and that nothing else can give me what my art does".

Certainly, this is true. Yet painting had something behind the scenes literature, without which some motifs or thematic series of his works would not have existed. He had an intense and pulsating feeling for literary language which linked him with magazines, newspapers, books and, finally, with men of letters. You could talk with Vincas abut poetry seriously. He was not afraid of transgressing the strictly observed boundaries of painting, he was fond of a polysemantic metaphor or pun, a good poem, a composer's new work. His serious literary gift is revealed in fragments of his reminiscences and diaries left in the archives, which are as picturesque and observant as any brilliant piece of literature. When these notes and diaries are published, the truthful picture of life at that time will emerge.

Vincas Kisarauskas was one of those rare "writing" painters, like Antanas Martinaitis and Leonas Gutauskas. He published articles, reviews of art exhibitions, research studies. His book "Lithuanian Book Plates" (1984) is one of the most comprehensive studies of art and culture history. As in painting, he abandoned himself to his work "with all his soul, fanatically". How much time, ingenuity, and patience was necessary in order to search for scattered materials, to look through various books, collect and classify book plates. He drew patience from another adamant researcher E. Laucevičius whom he helped to copy paper watermarks. Isn't it there that the renewal of book graphic art should be sought; wasn't it Vincas who aroused artists' interest in this branch of art, having created the first ex libris in 1961 ?

This was the other, less visible side of his life: a researcher-theorist, a scholar without any of the usual attributes degrees, theses or positions at scholarly institutions. His activity incited the revival of the small genres of art, combining seriousness with playfulness, ingenuity and constructing. His miniatures were marked by freedom, intimacy, sometimes a Kisarauskas-like humor. He knew how to characterize the addressee of his work by purely technical means. It was his merit that book graphic design came to be treated in a more modern way, not only by its utilitarian purpose. This field of work, with even more artists engaged in it, was one of the first to force its way into the wide world still locked from us, and to win recognition with Lithuania's name.

It is a meaningful, interesting and neatly written page of Vincas Kisarauskas' life and creative work. Now I am turning a new one.

* * *

Vincas Kisarauskas did not start to paint immediately at the Art Institute he changed over from textile. Nobody imagined him as a future painter, thus he had chosen to study ceramics at the Telšiai School of Applied Art and learned how to make pots. This "pot" craft does not seem to have disappeared, as Vincas always liked palpable things pure material, its texture and mass, pure color. He longed for the latter most of all while making pots in Telšiai; he used to say that something was missing, that he "wanted color badly". His teachers used to scold him that he saw too much color instead of arranging nature.

He did not "arrange" nature and did not intend to do it, since he loved it and learned from it. While looking through Vincas Kisarauskas' notes and fragments of reminiscences, I discovered nice literary sketches, descriptions of his impressions. It may appear strange that he never even tried to express those impressions in painting. His notes reveal the way he tried to be one with nature; he did not seek to rule over it, to impose the dictatorship of socialist realism on it. Here is what he wrote about the understanding of nature: "As a painter am interested in many things. I am just admiring nature, watching it, merely breathing it, taking it in with my eyes and senses; but this is not just being interested. Nature is a miracle, and while watching how the wind is tossing an alder tree, how its branches are swinging and swaying, and the same is happening all day long, I can see that it is a miracle, that it is such beauty which can be described in poetry only; it does not inspire me to paint".

At the Art Institute he drew from nature a lot; he used to say that he got "fed up with it" then. Having better familiarized himself with Western art, he took a firm decision:

"Nature is not to be copied". In his latest notes he left a kind of precept or will: "Do anything you want with it (nature M.M.), draw inspiration, observe it, learn from it, but do not copy it".

Already in Kisarauskas' student years his paintings departed from the mode of ordinary life; they may have never been close to it. This caused his teachers who observed his first attempts and who were ordered to keep their students in fear of the canons of socialist realism dissatisfaction. Already Vincas' early works stand on the strange border between the real and the unreal. The impression of unreality and strangeness is enhanced by palpable, real things found in dumps, mounted on assemblages and inserts, photographic portraits used in collages.

An important event which had influence on quite a few artists was the exhibition of Kisarauskas' paintings held at the Lithuanian Writers' Union in 1961. It was an explosion which considerably crumbled the structures of official art of that time, embarrassed some and opened a completely new world of painting for others. To the eyes of the time, his color combinations were most impossible and even abominable, making a "mockery of an artist" when he was broken in such a way. Jurgis Tornau recalls the discussion of this exhibition:

"A whole crowd of cultured people gathered in the room. I can remember the writer V. Mykolaitis-Putinas, the scholars of literature M. Lukšienė, I. Kostkevičiūtė, other writers and artists. Official representatives of the Artists' Union, careful of observing the postulates of state realism, expressed a negative view about the exhibited works. The intention of the silent organizers was to turn the discussion into a condemnation of the artist's works. It was the so-called reform method. Pitifully, the script failed, society's condemnation did not occur, quite contrary opinions, not coordinated with the 'higher organs', were heard."

This shows how difficult it was for people of Kisarauskas' generation to create real art. How many "instructions" had to be heard, how many traps had to be avoided! Fragments of modern Western art were hunted for, art albums "from over there" were scanned, books and articles were read. The eyes were like torch lights seeing through texts and reproductions; even trifles could draw attention and become topics of conversation and discussions. The fact that nothing remained unnoticed is revealed in Kisarauskas' impressions from the propaganda festival of the world's youth and students held in Moscow in 1957, where he caught glimpses of some works of modern art; "What disputes used to arise between advocates of new ideas and Stalinist art! The impression was phenomenal: even now can I see many of the works clearly, as then, with textures and colors, with all their emotional strength. The most important colors, with all their emotional strength. The most important thing which I understood was that there cannot be any rules for art; art is as diverse as people are: it is free in its basic nature. Later I experienced it myself: about 90 percent of my works done on commission are weaker than those created freely, for myself..."

Much had to be guessed at, imagined; he had to learn, to look for his way in the dusk of those dark times without any support, not even from his teachers.

* * *

Material, its structure, masses of figures, their penetration into space, "dark" color is the source of Vincas Kisarauskas' painting, artistic action, sometimes masculine, full of tension, sometimes dramatically brutal, sending a cold shudder, like suddenly having touched metal. You won't find polished surfaces and smart trifles pleasant to the eye. Everything is bulky, reminding one of blocks being constructed or deconstructed, as if some disintegrating or unfinished units cut by a self-sustained oscillator were having an argument among themselves. The center of action is the movement of color and mass, their dialogue or contradiction, their consolidation in spaces or surfaces.

This art belongs to a temperament little known to us: it seems to be distant from the Lithuanian coloring tradition; yet it is akin to a carving, forging, squaring master who models and fills into spaces, to an ancient carver of holy statues. The artist may have adopted from them the understanding of mass, its interaction with space and color. Perhaps it is one of Vincas Kisarauskas' oppositions in his constant search for balance stopping at a critical limit. In his works something always remains "slanting" so that power and mass affected by color could be felt.

Already in his early works the painter outlines his figures with "stained glass" contours, reinforces or consolidates them compositionally. They appear to hint at the future color "blocks" which are bound to become more and more autonomous, plastically unrelated to the background, contrasting with it by their outline or color, as if they had been installed or frozen there and were trying to move. One gets the impression that balance is sought in the general composition but simultaneously something is being ruined, turned, pushed. If everything stood in its place, it would become "pretty". The painter, having said "Too pretty", used to scrub off a fresh picture and begin everything anew. In this struggle against "the pretty" and "the good," he does not seem to have felt victorious.

His early "cast" figures, openness of color unusual at that time, the unconcealed process of mixing paints and their laying emerged, in my opinion, as the result of his two passions: for material and for color. That is why the color of these "metal' figures is on the inner, structural side; it is not an imitation of illumination or reflections, it reminds one of radiation emitted by the things which absorbed it, disintegration of strontium and caesium, if this disintegration could be seen in color. In some works an anticipation of the future Chernobyl seems to be felt.

Vincas' works created already during his student days seemed unusual and strange to his teachers and fellow students; they did not fit academic standards, he was infected by Munch and already sets himself different creative goals. Jonas Švažas, himself a good and remarkable colorist, taught the young painter: "Your color is wild. If you could tame it, it would be good". He chose his way intuitively and followed it until his last works. In the catalogue of his 1981 exhibition he writes: "Expressiveness and vigor of color, greater suggestion of paintings, new compositional structures were sought, a lot of new ways were tried in search of this only way, until finally it was realized that searching is nearly the truest way".

The chief motifs of his paintings and his means of composition were revealed in Kisarauskas' thematic series about King Oedipus, the Prodigal Son, in the cycles "The Knights", "at the Table" (the Emaus theme), the signs of the zodiac, theatrical compositions. These works are full of tension, anticipation and return to the same motifs, color relations brought perhaps from Central Lithuania, the dramatic darkness of its plains, the pure monochromatism of surfaces, divided by geometrical stripes. It is interesting to observe the evolution of this or that motif, the relation of horizontal surface and vertical figures. In the early works something reminiscent of Central Lithuania's plains with a lonely bending tree is represented. Later it becomes a figure of the Prodigal son or the Emaus theme. In this way the second level of comprehension linked with myth, sacredness, frightening mysticism, emerges.

To my mind, color is carried with oneself for all one's life, like one's mother tongue. With it man seeks to express himself, to relate his experiences, to realize what secret it contains. In the region of his childhood plains a pure color could make a great impact. The artist's wife Saulė told me how Vincas' mother used to get angry that he spoiled colors by mixing and shading them, while his father used to show him patches of pure color in his paintings which he liked. Vincas' fondness of color is evidently inherited from his parents, form nature, from his native village of Augmėnai, the compositions of which are so strict, consisting of surfaces and individual vertical objects or bending trees reminiscent of the return of the prodigal son and the Emaus themes.

Vincas Kisarauskas' colors are not so much "wild" and barbarian as dramatic; their mixtures are penetrating, painful. The eye accustomed to nice compositions is embarrassed by "heavy metal" emerging in his late works. The story is told, narrated not only by means of plot and mythic images, but also by this anxiety of color. There are also strange hints, guesses, reminiscences in the language of colors which was one of the first languages of man and nature.

This is why in the painter's works there is no joyful flickering, nor free improvisation, a feast of colors, their lure. He does not play or make jokes; to him color is too serious or even painful a matter. It is restraint becoming art.

n- * if-Distinctive features of Vincas Kisarauskas' painting are constructiveness of images, massiveness of figures, geometrical clarity and "readable" structure. He followed this path consciously, perhaps with a pinch of calculation. To the eye sliding over the surface of textures he looks too cold and constructive; as he overtly discloses compositional means, he does not .conceal the literary sources of his theme. Yet one soon realizes that this first recognition is not basic, that recognized images and things are no longer things, the same as words in a sentence or lines of poetry are no longer words, but that which occurs behind or over the text meaning, secondary authorship.

The painter asks and tries to answer: what is man, where does he go, what is his fate? He tries to realize it by specific means of painting, without illustrating journalistic or literary themes. The main source of action of his compositions is, in the author's words, "man, broken, chopped, scarred, deformed, but finally, be what he may, man all the same".

In the later works that man looks like some blown-up or dismantled mechanism, parts of which are scattered throughout the paintings, their surfaces, closed spaces... Since the first works the image of man of the "cast" figures constantly changes, assumes artificial, mechanical forms: a mask, a photo, a metal screw-nut, a cog-wheel... He turns into strangely assembled mechanisms reminiscent of a meat grinder, cast iron furnaces, menacing machines. I would not like to make these painting images literary by saying that the author shows man's alienation. Such a journalistic conclusion is not suitable here, since Vincas Kisarauskas' "metal" is "suffering" bound, cut, unable to liberate itself from the compressed spaces of the paintings.

This "acting" and "suffering" metal is an extraordinary feature of the artist's figurative painting. The years around 1965 could be considered the beginning of his creative evolution. At that time "The Knights" series was started, which changed basically the conception of expression and man's representation. It is a distinct transition from the half-expressionistic, Munch-like, rather lyrical period to the constructive, austere one. Lyrical color reflections, poetics of Lithuanian painting disappear. The painter begins to penetrate into the world of constructions, cold spaces and dramatic colors, cut space of several dimensions. Such is the space in his last works of the Prodigal Son cycle and in his almost testamentary work "Ismene and Antigone".

The painter's concept of space should be discussed separately, perhaps with more understanding of its meaning in the fine arts. Yet it is not difficult to notice how much significance the painter attached to it, seeking its relativeness, ephemeral illusion. In some paintings it now emerges, now disappears, and quite often is also "chopped', not uniform, of different depth and different, often reverse, perspective. The scenic space is also shaped in a similar way. Perhaps this is why the painter was so fond of theatrical motifs allowing him to alter perspectives. Intersection of-space-surface, "gradation of space' in his own words, is one more peculiarity or strangeness of Vincas Kisarauskas' art.

* * *

The period of 30 years of development of Lithuanian art dominated by an exceptional generation of artists is not yet realized. The true successors, programmers, performers of the art of this generation are not yet distinguished. At that time they were as if in the background of culture and creation, hidden in workshops, collectors' apartments; their works were passed out among friends. Now it is time for them to return to the public life of art some posthumously, others just recently discovered; belated classics who are changing the view of Lithuanian art of several decades. Isn't it the Emaus and Prodigal Son theme, isn't it a return to the homeland which has never been left? Will the faces be recognized?

It would be better to finish this sketch with Vincas Kisarauskas' words about the artist, Jonas Čeponis, uttered in the discussion of his exhibition: "To know your strength, your abilities and to use them all is very much! Not to bustle and rush about but to go deeper intently, to draw the bow given by nature the creative gift so that the arrow shot would fly as high as possible".

Vincas Kisarauskas' arrow is still in flight, though he himself is no more.

Vincas Kisarauskas was born in 1934 in the village of Augmėnai, the Radviliškis district. He died of a heart attack in 1988 in New York.

Translated by Aušra Čižikienė

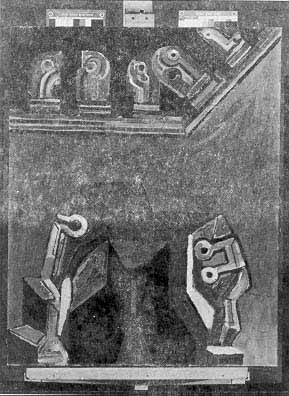

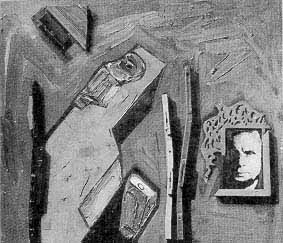

Vincas Kisarauskas. "The Twins of the Zodiac". 1977. Oil,

cardboard, montage; 115x104.5 cm. Photo by A. Lukšėnas.

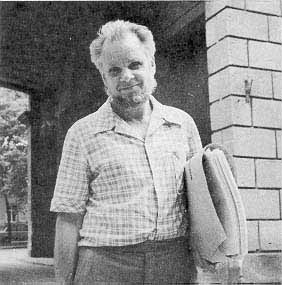

The artist Vincas Kisarauskas. Vilnius. May 1982. Photograph by Algimantas

Kunčius.

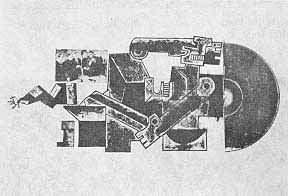

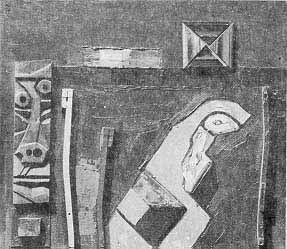

"Oedipus trying to guess his fate". 1986. Oil,

cardboard, collage;

40x124 cm.

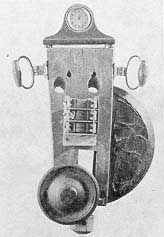

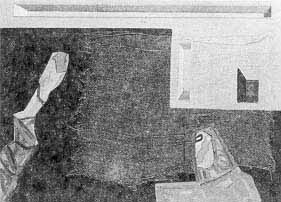

"Christ at Emaus". 1963. Cardboard, engraving. Photo by A.

Kunčius.

"Tannenberg". 1961. Mixed media. 37x64 cm. Photo by A.

Kunčius.

"Figure". 1970. Assemblage; 76x31 cm. Photo by A.

Kunčius.

"Self-portrait". 1976. Oil, cardboard, assemblage; 53.5x61 cm.

"Oedipus and Antogone". 1976. Oil, cardboard, assemblage; 53.5x61 cm.

"The Prodigal Son". 1981. Oil, cardboard, collage; 90.5x121.5 cm.

"Three Wednesdays". 1981. Linen engraving. Photo by A.

Kunčius.

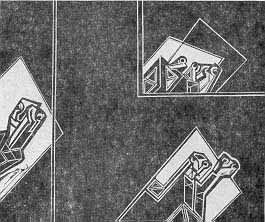

| Bookplates for Lithuanian writers | |

|

|

Algirdas Jackevičius M.D., 1978. |

Citta' di Pescara d'Annunzio. 1988. |

Dominykas Urbas. Tanslator, 1988. |