Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas

Copyright © 1996 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 42, No.3 - Fall 1996

Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1996 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

IT'S A BIRTHDAY PARTY!

Viktoras Petravičius would have been 90

SILVIA KUČĖNAS FOTI

Stickney, Illinois Roughly 20 devotees of Viktoras Petravičius huddled around a big square wooden table in the Galerija on Friday, May 3, 1996, to talk about a man who had died seven years ago, but who would have been 90 years old in just a few days.

The informal birthday commemoration of this Lithuanian artist was organized by his longtime friend Algimantas Kezys, photographer and owner of the Galerija, who wanted to rekindle the spirit of Petravičius in a way that the wood cutter might have enjoyed himself. Many of the guests had brought their own paintings by Petravičius to the Galerija, which occupies the second floor of Kezys' home. These guests had carried their prized paintings up the flight of stairs so that they could be displayed for inspiration while they dug up the memories of one of their favorite artists.

Apparently, this was a tradition. While the artist lived his last years in Union Pier, Michigan, he threw himself a birthday party every year, which included many of those who were present at this 90-year commemoration. The participants remembered how, during special occasions, Petravičius would wear a white suit with orchids, and many of them probably imagined him there dressed for the occasion.

That night, everyone was expected to share a memory of Petravičius with the other guests, and the evening began with a taped recording of the artist having an animated discussion with the host on art, religion, and sex.

Several who were there indicated that they have dedicated an entire wall in their home to the artwork of Petravičius, for he was someone who stood apart from other artists. But they admitted that Petravičius had also made a name for himself at exhibitions by refusing to share any wall space with other artists. They wanted to carry on his temperamental tradition because they respected him.

Everyone at the table seemed to know him very well, and little was said about the facts of his life. They already knew he was born on May 12, 1906, in Lithuania, that in 1935, he received a scholarship from the Lithuanian government to study at the Êcole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux Arts and the Conservatoire Nationale des Arts et Métiers in Paris. It was common knowledge that in 1937, he received the Grand Prix and the Diplôme Membre du Jury at the International Art Exhibition in Paris for illustrating the Lithuanian folk tale "Swan, Wife of the King." He married in 1940, and in 1945, he and his family moved from Lithuania to Germany because of World War II. In 1949, he emigrated with his family to the United States, and they settled in Chicago.

A few days after the commemoration, Algimantas Kezys, who has been documenting the painter since 1964, explained that Viktoras Petravičius went through several "periods" in his art, which coincided with the great changes in his life. His first period was in Lithuania until 1944, when his woodcuts were very romantic and lyrical in style and his subjects were Lithuanian folktales and mythological stories.

In Germany, his style changed and "he used rugged, convulsive lines that were very expressive of his feelings dictated by war atrocities," said Kezys. "His style became linear, structural, with flashes of lightning, women crying, scenes of the end of the world and burial services."

If you didn't know the man before, or if you only knew him through his art, the evening's discussion was a small revelation he was legendary and eccentric, traits that he seemed to have cultivated as carefully as he cut his wood for a graphic print. His life was one of prolific creativity that was accented by an intense and dynamic disposition. The memories flowed freely that evening as the participants shared some of their most memorable moments with Petravičius.

"It seemed you could only be his friend if you weren't afraid of him," said Dalia Kučėnas, a musician and writer. She remembered how after she had given a concert in 1975, Petravičius had complimented her by giving her one of his paintings. He inspired her to be original and go forward being true to herself, and his art motivated her to continue with her career.

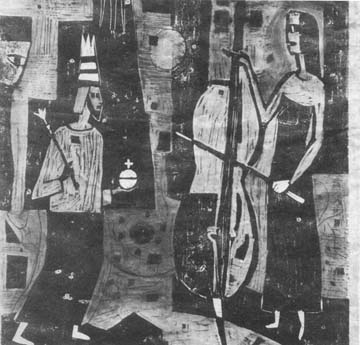

In one of the paintings that Kučėnas had brought that evening, a cellist was performing before a king who wanted to give him a scepter. The king apparently wanted to be as elevated in spiritual stature as the cellist, so the king wore a tall crown to become equal in height with the musician.

"He said you have to be nude as an artist; let your talent show completely. Don't imitate. Otherwise you're just a monkey, " she said. "The figures in his pictures always depicted feelings and emotions. "

Later Kezys explained that nude figures, male and female were very dominant in Petravičius' graphics. "The nude figure was a constant in his life. He identified the feminine body with the earth, with the mother of all creation. "

When Petravičius and his family immigrated to the United States, he found a job working in a steel manufacturing plant in Cicero, Illinois. "He had a hard time earning a living during this period, and he didn't do much creative work, " said Kezys. "He did some miniature oils, stained glass for churches, and mini-mosaics embedded in cement, but basically for the next ten years he had a barren period. "

By 1961, a new period of vitality began for Petravičius, and he had his first one-person show in Chicago. "He exhibited newly created work in black-and-white woodcuts, in which the blacks were very dark and the whites were pure, " said Kezys. "The woodcuts were full of symbols and images, such as the king, a girl, human figures, animals, deer, and bulls, which he used over and over throughout the years. "

He had one show after another. He began experimenting with color in 1963 by splashing paint on the canvas, which was very much in vogue during that time among artists living in the United States, explained Kezys. However, his followers didn't like this new style, and told him that they preferred his work in black and white. He never used that particular "splash" technique again.

"But he continued experimenting with color, and by 1964, he finally got a hold of it and never deviated from this new method, " explained Kezys. "These color creations became wonderful pieces worthy of his talent. The idea was to take the black-and-white image from the woodcuts and then hand color part of the image, such as the background. These became his oil graphics. "

Petravičius turned to the woodcuts he had created in 1960 and reprinted them, but this time he added color by hand. He also combined up to four wood cuts that he had fashioned years earlier, placed them side by side, and printed them on one long sheet of paper.

During this time, he was able to support his family from the sale of his artwork and by teaching art to students. One of his most prolific students was Magdalena Stankūnas, also a woodcutter graphic artist who used color in her lyrical and romantic paintings.

"He worked very fast, " Stankūnas remembered that evening. "He always told me not to worry about the details, to summon up courage, to forge ahead. He gave me confidence in myself. "

Petravičius and his family lived on Claremont Avenue in Chicago near a railroad track in a small bungalow. He had four children, two girls and two boys. One daughter died when she was four in 1946 and his youngest son, Peter, died in a tragic train accident in 1967. After his son's death, his prints became dark and very black, in which he kept repeating the figure of a pregnant woman, explained Kezys. "The accident affected him greatly and he expressed his feelings in his art. He was man who could never lie. He was very true to himself, no matter what others said about him".

Vytautas Vepštas, an architect, remembered when Petravičius called him a few years after his son's death to do some investigative work in figuring out how much it would have cost the train company to build a fence that could have avoided the train accident of his son. Petravičius was going to use this information in a lawsuit against the train company, but Vepštas never knew what happened of the intended suit.

Vepštas also remembered when Petravičius called him in 1972 to design more space for his home that was getting too small for the family.

"We decided that we needed to raise the roof to create an attic, " said Vepštas. "In repayment, he had given me the engraved linoleum used for his Spring series. When he was in Germany, he couldn't get any wood, so he ripped up the floors for the linoleum. Art was the most important thing to him, and it never mattered to him if he didn't have exactly the right materials. Anyway, I noticed that the corners of this linocut were frayed. Apparently, the roll of linoleum had hardened over the years, so he put it in the oven to soften it before giving it to me. His technical motto was always 'Just do it; it doesn't matter how'. "

In 1979, Petravičius and his wife moved form Chicago to Union Pier, Michigan. His best years were yet to come, said Kezys. He moved away from the noise in the city and lived among the trees and next to the lake. For the next three years, he had one-person shows in Chicago at Kezys' Galerija, in the River North area. In 1983, the Museum of Art in Vilnius hosted an exhibition for him, and in 1984, he exhibited what Kezys considers to be his best work at the Midwest Museum of American Art in Elkhart, Indiana, which acquired many of his masterpieces.

Aldona Markelis, an old friend, remembers how she had brought some wild strawberries to his home in Union Pier, and how grateful he was for receiving the berries that reminded him so much of Lithuania. He planted a patch of wild strawberries in his garden, which for years afterward, became one of his favorite places. In repayment for these berries, Petravičius had given her a painting.

Vytautas Zalatorius, a political writer, had often stopped by the home of Petravičius in Union Pier, after attending nearby meeting of Santara-Šviesa, a literary Lithuanian group. All newcomers, particularly the men, who came to the home of Petravičius were required to bring a bottle of cognac, said Zalatorius. They also were asked to sign their name on the big oak table. Each signature on that table had signified a bottle of cognac and a new friendship.

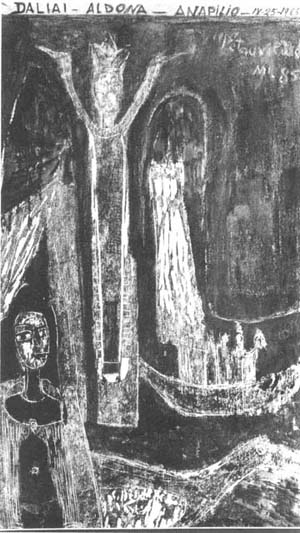

Petravičius continued to be very productive until 1985, when his wife Aldona died. His style changed again and became very morose, noted Kezys. Petravičius made four prints of his wife on her deathbed with an oxygen mask on her face.

"His black and white and colors were becoming subdued, as if they were receding, " said Kezys. "He went back to just black-and-white prints again, but they were not as stark and clearly defined as his earlier pieces. He was not cutting wood at this point, but applying black print to a flat board and printing paper from this board.

"The last print he produced in his life is a series in which the black is almost transparent and the figures were barely visible, as if they were in a mist. It was very symbolic of his feelings, as if he knew the end was near and his health had deteriorated. "

Aldona Kaminskas, an optometrist, recalled his words after his wife, Aldona, died. "What will I do without Aldona?" he had asked. Shortly afterward, he became sick and Kaminskas remembers how he told her on Father's Day: "Nothing is left. My days are numbered. " In August, his daughter called Kaminskas, asking her to come over.

"Twenty minutes later, he died, " Kaminskas said. "He was lying in the bedroom with his family surrounding him. His grandchildren started to race each other to see who could pick the most autumn flowers for their grandfather. As the room began to fill with the flowers, the scene turned very surreal. I couldn't even cry. Next to his bed, there was a table with flowers, Aldona's photo and a little Lithuanian flag. His daughter took out his famous white suit, which he wanted to be buried in. "

The visitors sat around this low wooden square table that was covered with his art books and catalogues of his exhibitions, each drinking a glass of red or white wine. They gathered together and surrounded themselves with his artwork for one reason to remember someone who had a profound effect on them, not only through his expression in his art, but also in the way he lived his life and the way he related to his friends directly, primitively, and deeply.

The home of Viktoras Petravičius in Union Pier is being converted into a museum. Algimantas Kezys is working on a three-volume series on Petravičius. Volume I, published in 1991, covers his early period in Lithuania and in Germany until 1949. Volume II will include his work from 1950 to about 1975, and Volume 3 will include his last years.

If you are interested in obtaining volume I, please write to Galerija, 4317 South Wisconsin Avenue, Stickney, Illinois 60402. The Art of Viktoras Petravičius, Vol. I. Edited by Algimantas Kezys. Hardbound. 234 pages. ISBN 0-9617756-3-7. $25. 00. Add $2. 50 to cover postage.

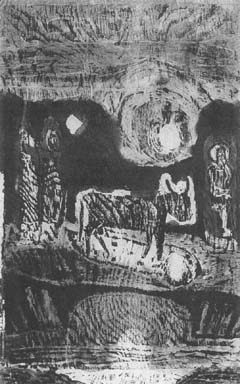

In the Pasture, 1961, woodcut

From the series "Marti iš Jaujos" (The Bride from the Barn), 1938, woodcut

Available, 1970, oil graphic, 28" x 14"

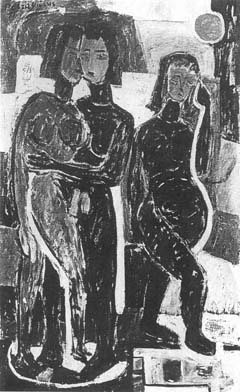

Figures, #4, 1971, oil, 48" x 14"

The King and Seven Wives, 1975, oil graphic, 26" x 24"

The King and Violoncello, 1974, oil graphic, 24" x 20 1/2"

Sacred Land, 1982, oil graphic, 38" x 23"

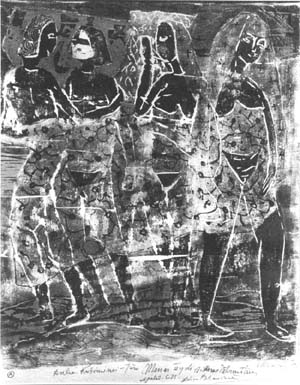

Daliai Kučėnienei (To Dalia Kučėnas... ), 1975, oil graphic, 26" x 20"

Exodus, 1982, oil graphic, 37" x 22"

Daliai Aldona Anapilio (To Dalia... ), 1985, oil graphic, 32 1/2" x 19"

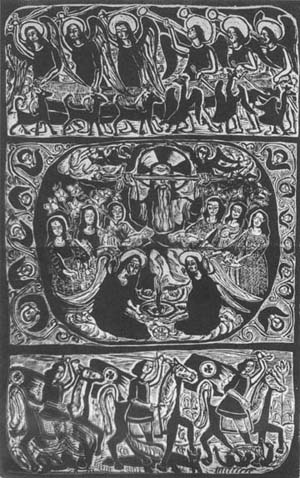

God's Judgement, c. 1949, linocut, 17 1/2" x 18"