Editor of this issue: Dalia Kučėnas

Copyright © 1996 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 42, No.4 - Winter 1996

Editor of this issue: Dalia Kučėnas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1996 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

JŪRATĖ IR KASTYTIS BY KAZIMIERAS VIKTORAS BANAITIS:

A LITHUANIAN OPERATIC VERSION OF THE LORELEI-UNDINE MYTHS

ENRIQUE ALBERTO ARIAS

School for New Learning, DePaul University

Composer Kazimieras Viktoras Banaitis

I do not know what is the meaning of my sadness. A tale from the old times comes to me. The air is cool and it is becoming evening. The Rhine flows peacefully. The top of the mountain sparkles in the evening sun. The loveliest maiden sits up there, marvellous. Her golden jewelry gleams. She combs her golden hair. She combs it with a golden comb and sings a song at the same time. This song has a strange, imposing melody. The song seizes the boatman below with wild sorrow. He does not see the reefs, for he can only look upward. I believe that at last the waves swallow the boatman and the boat. The Lorelei has done this with her singing.

Heinrich Heine, Die Heimkehr

The April 1996 performances by the Lithuanian Opera Company of Chicago of Jūratė ir Kastytis by Banaitis has inspired the present reconsideration of this major Lithuanian opera. Completed in 1955, Jūratė ir Kastytis was composed in the last years of the composer's life, when he was almost destitute and suffering from Parkinson's disease. Based on the ancient Lithuanian legend of the love of a sea sprite for a mortal on the shores of the Baltic, this opera is related to musical settings of the Lorelei and Undine myths myths which have much in common with that used as the basis for this opera. It is within this context that I will discuss what has become one of the most influential Lithuanian operas of the century.

Although Kazimieras Viktoras Banaitis (1896-1963) composed in different styles and genres, he is now known principally for the composition of this opera. He began his musical studies at a private school of music in Kaunas, 1911-14. From 1922-28 he studied composition, piano, and musical pedagogy at the Conservatory of Leipzig, where he studied, among others, with the important German composer Sigfried Karg-Elert. After his studies in Germany, he returned to Lithuania, where he was the director of the Kaunas Conservatory from 1937-44. Because of the Soviet occupation, he left for Germany in 1944 and then went to the United States in 1949, where he spent the rest of his life. He lived in Brooklyn, eking out a precarious existence giving private lessons and working at minor musical positions.

His music received little attention during his lifetime, even from the large Lithuanian communities living in the United States. Banaitis was not a promoter of his works, preferring to think of composition as a pure task separate from practical affairs. In general, his music is rather conservative, with a clear emphasis on the folkloric. Modality, altered scales and chords probably an influence from the Impressionists and quintal harmonies prevail. He wrote a large number of choral arrangements of Lithuanian folk songs as well as chamber compositions.

Jūratė ir Kastytis, the work Banaitis considered his masterpiece, is on a larger scale than his other compositions and more fully explores various contemporary devices. As mentioned above, it was completed in 1955, though Banaitis spent the next five years refining its Contents. In 1960 it was presented to a special committee who were charged with the publication and performance of this opera. It was premiered by the Lithuanian Opera Company of Chicago on April 29, 1972. The original cast was the following:

Jūratė Dana Stankaitis

Kastytis Stasys Baras

Rūtelė Margarita Momkus

Mother of Kastytis Aldona Stempužis

The conductor for the performance was Alexander Kučiūnas. The orchestration was done by James T. Kilcran.

The libretto by Bronė Buivydaitė is based on the ballad Jūratė ir Kastytis (1920) by Maironis (actual name Jonas Mačiulis). The essentials of the story concern a mortal who falls in love with a sea nymph. This love affair is fated not to last because of the jealous god of thunder who destroys the sea nymph's underwater palace. The earliest mention of this legend occurs in 1842 in the writings of Liudvikas Adomas Jucevičius. This legend was viewed as the explanation of amber, the Lithuanian national stone, which was carried ashore after the destruction of Jūratė's amber castle by the god thunder.1

This legend is held to have considerable nationalistic importance and can be viewed as explanatory of the origins of Lithuania as a self-sufficient country. Juozas Gruodis used the legend as the basis of a ballet in 1933, while the playwright Aleksandras Fromas-Gužutis conceived his 5-act drama Jūratė, the Goddess of the Sea (1955) from the legend as well. In addition, Lithuanian sculptors and painters have used this myth as the basis of their work. One of the principal examples is the sculpture of "Jūratė ir Kastytis" that stands in the main street of the resort city of Palanga.

This legend is somewhat related to the Undine and Lorelei myths popular in Germany because of the common emphasis on the destructive relationship between a mortal and spirit. In Lithuanian folklore sea nymphs are immortal goddesses who have magical powers, but they lose the gift of immortality when they fall in love with a human. It is their immortality and special powers which set them apart from their human counterparts and make any union impossible.

The Undine and Lorelei myths and their variants fascinated 19th and early 20th century composers. Both were formulated in written form in Germany in the early 19th century, although their roots probably lie in earlier oral traditions. As early as Homer's Odyssey (c. 8th century B.C.), for example, one finds stories of mortals enchanted by the songs of spirits associated with the sea. It will be remembered that Odysseus has to stop the ears of his sailors and lash himself to the mast in order not to be diverted by the song of the Sirens.2

Lorelei is an echoing rock in the Rhine near Sankt Goarshauen, West Germany. According to the Encyclopedia Britanica, Lorelei was a maiden who threw herself into the Rhine in despair.3 She was transformed into a siren who lured fishermen to destruction. The essentials of the story are present in Clemens Brentano's novel, Godwi (1800-02). As is clear from the Heine poem presented at the beginning of the article, Lorelei is, like the Homeric Siren, a spirit that calls from the land.

Undine, on the other hand, is a water sprite who marries the knight Hildebrand to acquire a human soul. She later loses this human love because of the treacheries of her uncle Kuhleborn and the lady Berthulda. The first telling of this tale occurs in the fairy tale Undine (1811) by Friedrich Heinrich Karl de la Motte (better known as the Baron Fouque).4 Both the Lorelei and Undine novels reflect the intense early Romantic German interest in folk stories that have nationalistic implications.5

There is a Slavic version of the myth as well that is used by a number of influential opera composers. Alexander Sergeyevich Dargomyzhsky's Russalka (1855) is on a libretto by the composer himself, but is based on Pushkin. The most famous version of this variant of the myth occurs in Antonin Dvorak's Rusalka (1901), libretto by Jaroslav Kvapil. This opera is also based on the story The Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Andersen. As the composer himself said:

I received my inspiration in the land of Andersen, on the island of Bornholm, where I was spending my summer holiday. The fairy tales of Karel Jaromir Erben and Božena Nemcova accompanied me to the seashore, and there they merged into one of Andersen's fairy-tales, the love of my childhood days, and the rhythm of Erben's ballads, the most beautiful of Czech ballads.6

It is clear from the above that parallels exist between these versions of what may be considered a universal myth. They receive attention during the Romantic period, or that time during which folk mythology is used as sources for literature but also for the creation of national identity. A common theme is that of a spirit, either from the sea or near the sea, who brings destruction to a mortal man. The Lithuanian variant, however, highlights the sea nymph's divinity and the importance of amber as a national stone a stone commonly found on the shores of the Baltic. It is possible that the 19th century Lithuanian authors cited above were aware of the work of their Slavic and German counterparts.

Operatic settings of the German myths appear within a decade after the publication of the novels cited above. E.T.A.Hoffmann, the great German writer and composer, wrote an opera entitled Undine (1816). Donald J. Grout has noted its importance:

In Undine, his best opera, the earlier merely fanciful play with fairy elements is given a feeling of human significance, thus achieving some dramatic force in spite of a complex and fantastic plot. The music suffers from some technical faults, but the romantic mood of Weber's Freischutz is distinctly foreshadowed, especially in the scenes depicting supernatural beings and in the many folklike melodies and choruses.7

Albert Lortzing, best known for his lighter operas, also composed an Undine (1845), which is more serious and on a larger scales than his other operas. Grout also discusses this work:

Lortzing who in all these works was his own librettist ventured on the ground of romantic opera, with its supernatural beings and theme of redemption through love. Lortzing was hardly capable of composing music equal to the emotions and characters of this libretto, but his systematic use of recurring motifs and his powerful musical depiction (especially in the water-sprites' music, first heard in Act II, scene 5) are interesting both in themselves and as predecessors of the music of Wagner's Ring8

These now forgotten German operas have important Romantic traits and prefigure symbolic and musical elements of Wagner's Ring. They also create a tradition of setting this powerful myth that would continue into the present century.

In addition to the works cited above, the following are major versions of the Lorelei legend:

Franz Liszt, Die Loreley (1841) (an extended setting for voice and piano of the Heine text cited at the beginning. There is a second version as well as a transcription for piano and an orchestration of the piano part.)

Felix Mendelssohn, Die Loreley (1847) (an unfinished opera on a libretto by E . Geibel)

Max Bruch, Die Loreley (1863) (a complete version based on the libretto for the Mendelssohn opera) Alfredo Catalani, Loreley (1888) Hans Sommer, Loreley (1891)

Undoubtedly, the most important purely orchestral setting of a sea nymph myth is Mendelssohn's overture The Fair Melusine (1833), which features an arpeggio figure for clarinets to depict the water sprite. This overture and this particular motive influenced the opening of Wagner's Das Rheingold (1869). The article on Mendelssohn in The New Grove Dictionary of Music notes:

Grillparzer had adapted the Romantic legend of the mermaid Melusine as an opera for Beethoven, who eventually decided against setting it. After Beethoven's death Conradin Kreutzer took up the libretto and set it as an opera commissioned by the Konigstadtisches Theater in Berlin. Mendelssohn saw a performance in the spring of 1833. He disliked Kreutzer's work but expressed the wish to write his own overture based on the subject; in it he combined a penchant for depicting moods aroused by the sea with the expression of lovers' joy and sorrow, all within the broad framework of the legendary subject.9

Elements of Undine legend are included in the importance given water sprites at the beginning of the Das Rheingold, which, as we have seen, is musically influenced by some of the works cited above. Ravel's Undine, the opening movement of his virtuosic cycle for piano, Gaspard de la Nuit (1908), is probably the most important treatment of this legend. Ravel's rich harmonic vocabulary and intricate piano figurations fully capture the essence of this mysterious sea figure.

Additional settings of the Undine story are: Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Undina (1869), (an opera Tchaikovsky wrote quickly and for which he received bad reviews) Hans Werner Henze, Undine, a ballet (1958)

It is unclear whether Banaitis was aware of any of the Lorelei, Undine or Russalka operatic settings mentioned above. He may have heard about the Hoffmann setting during his studies at Leipzig, given its historical importance. He must have known Mendelssohn's overture, which is part of the standard repertory, and probably was aware of Ravel's piano piece. But another opera clearly exercised a strong influence, Debussy's Pelleas et Melisande (1902), based on the play by Maeterlinck. The dream-like symbolism of the play, the mysterious atmosphere of the opera, and its Impressionistic musical language influenced all opera composers of this century. More specifically, the declamatory voice style and fragmentary motives of Pelleas et Melisande are similar to those features in Jūratė.

In order to understand the musical analysis of this opera, the following synopsis (included in the 1996 program book for the opera) is presented here.

JŪRATĖ IR KASTYTIS Synopsis

Act I, Scene I. In Lithuania, on the shores of the Baltic Sea, stands an ancient fishermen's village. Here men through the centuries inherited the skill for fishing as their very lives depended on it. It is late afternoon. The fishermen, preparing to sail, are singing lustily: "O sea of beauty why do you roar? Why do you sigh? Are you expecting guests? They sing on, their silver nets spread wide: they will snare a mermaid, a water sprite of the green sea. For their sisters or their loved ones they will bring back pearls of amber and golden fish. Maidens and wives arrive to see them off, to wish them good fortune and a safe return. The fishermen pray to the God Perkūnas, asking his blessing on their trip and the forestalling of wicked wind. They bid farewell to their dear ones and leave.

Kastytis arrives late. He looks wistfully out to sea and sings a song of yearning. From the sea, the fishermen answer his song, awakening Kastytis from his reverie. In the distance, Jūratė rises from the sea intently listening to his song and comes toward Kastytis. Bewitched by her beauty, Kastytis is speechless. Jūratė sings "Kastytis, forget your earthly dreams, a beautiful new world awaits you." Recovering from his awe, he asks Jūratė: "Who are you? Where do you come from?" Jūratė replies: "The winds bend at my command, and at my word turbulent becomes the sea. I rule the green sea and I love you, Kastytis."

Kastytis tries to resist her charms. He loves Rūtelė. However, Jūratė continues her wiles. Mermaids (Undines) appear from the sea, singing to the rhythm of the waves: "When the moon rises, making a golden path in the skies, the sea will blossom with pearls." Slowly coming forward they continue, "We know no pain, nor death, nor suffering; we are young eternally!" The sorceresses sink into the sea.

Kastytis, as if awakened from a haunting dream, repeats the words of the mermaids and Jūratė. Dazed by these wordless words, and such beauty, he is exhilarated as by fiery wine. He is bewitched. Jūratė persists relentlessly: "Kastyti, when your boat kisses the waves, my sea maidens will meet and gently rock it, and strewing wreaths of roses in his pathway, they will guide you to where I will be lovingly awaiting you. My amber chambers will gleam with the brilliance of lightning. Kastytis is bewildered by Jūratė's expression of love. Is this real, or is it a dream? It seems the whole world is passionately aflame.

Enraptured with the singing and beauty of Jūratė and mermaids Kastytis hurries towards his boat. With a soaring song he sails away. The scene ends with Rūtelė rushing in and sorrowfully watches Kastytis sail away.

Scene II. It's morning. Maidens mending fishing nets are singing: "The sea beckons to our loved ones, while we mend the nets." They do not notice the approach of Kastytis' mother who is searching for her son who did not return with the other fishermen. She muses: "The sea is so clear and quiet, the waves ripple so softly. Why hasn't Kastytis returned... maybe the Gods are angered?" Mother notices Rūtelė who watches the sea and in deep sorrow waits for Kastytis. Both women have a short conversation. Mother tries to console the young Rūtelė, but to no avail. She leaves while Rūtelė sings her plaintive aria.

Finally Rūtelė cries out: "Kastyti, Kastyti! Where are you now?" and suddenly she sees a vision: it is Kastytis sailing at sea.

Here Kastytis sings a most impressive aria, a Barcarole, titled, "Laivyne" (A Boatman's Song) from the pen of a foremost Lithuanian poet, Balys Sruoga, which the composer K.V. Banaitis inserted into this opera.

As a vision disappears the voices of Jūratė and the mermaids are heard in the distance.

Act II. Scene: Jūratė's amber palace, at the bottom of the sea. After a short musical introduction the curtain rises on a scene of mermaids dancing and joyously singing of the wonders of life in the sea.

As Jūratė and Kastytis descend into the sea, they sing a duet, expressing their rapture for life and love. The mermaids lead them to the throne, strewing their path with roses, then break into wild, happy dancing, singing, "This is Jūratė's wedding festival." From the distance comes a clap of thunder. It rolls in closer and louder. The dancing subsides. Thunder increases. Jūratė commands the winds to raise the soaring waves to their highest, to greet Perkūnas, the God of Thunder, with the greatest of joy. The thunder becomes ominous. The Sea Winds warn Jūratė, Perkūnas is threatening a horrible revenge because she, a Sea Goddess, dared to love a mortal. Only a God should have been her choice. She can avert his wrath only if she renounces her love for Kastytis, and he returns to earth!

Jūratė rises from her throne, comes forward and proclaims: "Winds! My brothers! I do not fear the threats of the Gods! What can they do to me when my heart is filled with the fire of love? I rule the sea! Winds, my fleet ones! Tell the Gods: Jūratė loves a son of the earth." Kastytis to Jūratė: "If we are to die, we shall perish together." The Gods send down their wrath. Winds die down but thunder roars. The amber palace darkens, lightening strikes.

Kastytis and Jūratė stand ready to meet death. The mermaids, caught up in the tempest, dance wildly. The Sea Winds once more warn Jūratė that death is near. But Jūratė has no fear of dying with her beloved. With one last, violent clap of thunder, lightening shatters the amber palace. Darkness. The storm subsides.

The ravages of the storm leave Kastytis deeply desolate and barely alive, chained to a rock on the shore. In retrospect he remembers Jūratė, his mother, his friendly fishermen, his home where the sun was always bright and where the wind softly murmured through the fir trees. He will never see them again. From far away, like the echo of a dream, he hears the song of the fishermen.

Jūratė falls into three acts, although the first two are usually combined in performance. The opera begins with a prelude whose repeated motive establishes the atmosphere of the opera and stands for the call of the sea nymph. The tritones, augmented triads, and implied whole tone scale immediately identify the musical language as Impressionistic. (Example 1)

This is followed by a long chorus in praise of the sea divided between the men's and women's voices. The women's voices often move in parallel thirds followed by the full chorus. Repeated phrases moving in thirds and dialogues between the upper and lower voices confer a folkloric atmosphere. In addition, the frequent choral sections and their meditative character make the work somewhat cantata-like. (Example 2)

Kastytis enters to sing a song of longing for the sea. Notable is the emphasis on the tritone the interval used in this opera to connote mystery and yearning. (Example 3)

Typical of Lithuanian folk music and of this opera is the use of short repeated motives based on conjunct melodic patterns. This feature is found in the chordal underpinning for this scene. (Example 4)

Jūratė enters to answer Kastytis with an invitation to join her in the sea. The music for her aria grows out of the previous musical materials. As can be seen in the example just cited, parallel thirds and a rich modal harmonic vocabulary are employed throughout this section.

An interlude for the Undines is then heard. The use of the word "Undinės" at this point of the score clearly relates it to the Undine works mentioned previously. As can be seen in the musical examples presented thus far, the musical style is quite unified. By this point in the score, it becomes clear that musical materials are derived from each other without repeated themes in the traditional sense.

Rūtelė enters. Her cry of farewell is marked by the descending fourth, often a controlling interval in the major solo sections. (Example 5)

Kastytis is torn between his love of this earthly maiden and the sea nymph, but in the end decides to follow the call of the sea. The act ends with the motive of descending thirds that had been important at its outset. (Example 6)

The second act begins with a simple prelude. This is followed by a duet between Kastytis's mother and Rūtelė, accompanied by a chorus of the women. Continuous fifths in the lower texture create a folk-like effect. (Example 7)

The highlight of this act is the Barcarole sung by Kastytis. The words are by the poet Balys Sruoga, and the Barcarole was inserted as a self-contained section after the composition of the rest of the opera. The two-bar phrases that have been typical of the opera as a whole are emphasized here. (Example 8)

Kastytis answers his father's question by noting that his happiness consists in being a part of the sea. The enchantment between Jūratė and Kastytis is complete as the music reaches a climax. (Example 9)

This act, which, as mentioned above, is usually performed as the second scene of the first act, ends in B major, the key associated with Jūratė and the union of the two protagonists. Also heard here is the motive of descending parallel thirds. (Example 10)

The third act is relatively short and takes place in Jūratė's amber chamber. It begins in the key of B major, thus continuing the ending tonality of the previous act. The song of the Undines is based on musical ideas from the first act. (Example 11)

Jūratė and Kastytis here sing a duet of bliss, related in style to their duet in the first act. (Example 12)

A dance for the Undinės follows which again uses open fifths, thus relating it to the previous dance episode.

The bliss of the two is threatened by the god of Thunder, signaled by a change from clear tonality to an emphasis on the tritone, heard also at the beginning of the opera. (Example 13)

Tonal ambiguity prevails throughout this section, though there are strong references to the key center of B as Jūratė rebukes the winds. (Example 14)

Kastytis regains his courage as he sings that he can face anything. This climatic section of the opera recapitulates previous thematic material in varied form. When the Undinės sing that the wrath of the gods will destroy them, the tritone is sounded. (Example 15)

This is followed by a response by Jūratė and Kastytis using a declamatory style and emphasis on the interval of the fourth. This interval is also found at their entrance in the first act and is used to highlight important statements. The tonal center of D prevails at this point, though a shifting between major and minor occurs as the emotional tension heightens.

Kastytis sings that he has lost Jūratė as well as his family as the opera comes to its conclusion. Here the music of his desolation moves to Bb minor, the most distant tonality from B the only time in the opera that this tonality is found. Example 16)

This distance of tonality symbolizes his loss of Jūratė and his dream of a life with her in the sea symbolized, as indicated above, by B major.

Jūratė ir Kastytis has a high degree of organic unity created through the motives built on perfect fourths or tritones and the key schemes mentioned previously. In particular, the key of B dovetails the two final acts. The perfect fourth is used for straight-forward narrative, while the tritone implies either longing or despair.

Two styles are emphasized: a modal, folk-like simplicity, and the harmonic procedures of the French Impressionists. The latter style, appearing in sections of doubt and conflict, highlights tonal ambiguity through the tritone and chords built on fourths.

The choral sections anchor the works structure as well as comment on the emotions of the protagonists. There are major choral and dance episodes throughout, occupying as much of the opera as the music for the protagonists. This emphasis on the chorus is reminiscent of Mussorgsky's Boris Godounov (1868-69). At the end of the opera, for example, Kastytis is reminded of his loss through hearing the chorus of fishermen.

Most of the solo writing is handled in a declamatory manner. The most important exceptions to this are the Barcarole and the duet at the end of the first act, where a more cantabile style is employed.

In general, the opera moves at a slow dramatic pace. Although this can be considered a fault, it should be noted that this is quite typical of French symbolist drama a tradition that I believe Banaitis was working in. In summation, Jūratė ir Kastytis not only begins serious contemporary opera in Lithuania, but it is also a minor masterpiece within the operatic repertory as a whole. Its telling of the common European myth of the bewitchment of a mortal by a sea nymph in a highly unified and structurally well controlled plan gives it this place of honor.

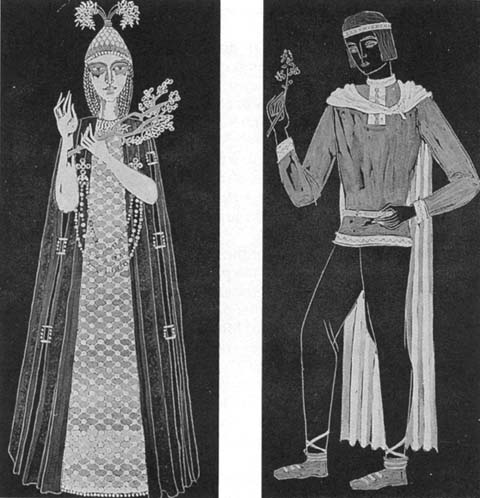

1972 Lithuanian Opera production of Jūratė ir Kastytis. Costume design for the third act by Adolfas Valeška.

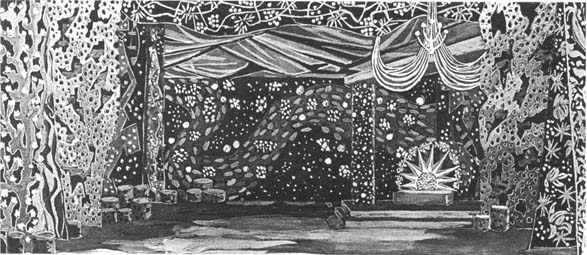

1972 production of Jūratė ir Kastytis by Lithuanian Opera. Third act scenery sketch by Adolfas Valeška

1 I wish to thank Dr. Dalia Kučėnas for help with the mythological background of this opera as well as providing the initial materials necessary for research.

2 Homer, Odyssey, Book 12, 11. 240ff.

3 The New Encyclopedia Britannica, Micropaedia, v. 7, 479.

4 lbid.,v. 4, 903.

5 On the other hand, in many traditions, the sea is viewed as a source of life. The most famous example of a Neo-Platonic depiction of this concept is Sandro Botticelli's The Birth of Venus from the Sea (c. 1480). The Lithuanian anthropologist Maria Gimbutas has written an important book in which she discusses ancient sea goddesses as sources of fertility and creativity: The Language of the Goddess (foreword by Joseph Campbell) (San Francisco: Harper & Roe, 1989). Jūratė should be thought of as belonging to this tradition.

6 Quoted in Neil Butterworth, Dvorak, his life and works (Kent: Midas Books, 1980), 121.

7 Donald J. Grout, A Short History of Opera, rev. ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1965), 381.

8 Ibid., 390.

9 Karl-Heinz Kohler, "Felix Mendelssohn," The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (1980), v. 12, 149.