Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

Copyright © 1998 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 44, No.3 - Fall 1998

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1998 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

THE HUMAN FIGURE IN THE WORK OF VYTAUTAS KAŠUBA*

IRENA KOSTKEVIČIŪTĖ

Institute of Culture, Vilnius

In early fall of 1944, at the time when Vytautas Kašuba was fleeing from Soviet tanks to the West, Vincas Mykolaitis-Putinas completed "Vivos Plango, Mortuos Voco" ("I Mourn the Living, the Dead I Set Free"), the famous apocalyptic conspiratorial poem which prophetically proclaimed the domination of "the heroes of misfortune."

In 1944, the poet Juozas Kėkštas also prayed "The Father and Son to Return to Earth," as he fought in bloody battles against German divisions near Monte Casino.

Balys Sruoga, facing death in a Nazi concentration camp, spoke of the macabre inquisitors of the new times, in Forest of the Gods published in 1946.

In 1947, the terrible afflictions of modern existence were analyzed in two great epics of the era, The Plague, by Albert Camus, and Doctor Faustus, by Thomas Mann.

Among the Lithuanian refugees in America, Antanas Škėma with painful irony surveyed the grimness of those times in his novel The White Shroud published in 1958.

A world maimed by the absurd and abounding in the grotesque images of war unfolded in the book by Marius Katiliškis, For Those Who Left, There Is No Return (1958).

In 1962, the wrathful destruction of life was depicted in a collection of poetry entitled The Generation and Offspring of a Non-Ornamental Language, by A. Mackus.

Already widespread by the middle of the twentieth century were works reflecting European totalitarianism and the general crisis situation that conveyed the artistic and philosophical perception of existential absurdity occasioned by the catastrophic events of the time. Touching on the link between individual creativity and the epoch, Jung noted: "The artist does not follow an individual impulse, but rather a current of collective life which arises not directly from consciousness but from the collective unconscious of the modern psyche. Just because it is a collective phenomenon it bears identical fruit in the most widely separated realms, in painting as well as literature, in sculpture as well as architecture."1

Vytautas Kašuba absorbed the atmosphere of the great tension of his times as he lived the drama of the individual caught up in them, and spoke out through original and innovative sculptural forms. From 1969, to 1973, the sculptor produced a series of hammered lead relief that sprang, as it were, from the depths of the "unconscious of the modern psyche." In these works, against an endless background void, dreary, solitary figures - shouting, resigned, yearning, and suffering - emerge as existential portrayals of the human condition, stemming from the author's personal experiences "upon leaving my homeland, witnessing the pain endured by humanity and facing my own fate."2 These works were created in his free time between major commissions. There is a spontaneity in them, born as if of their own accord, as if they had sprung into being in a single breath, they can be compared to intimate entries in a diary, where there is no boundary between impulse and statement.3

Vytautas Kašuba links closely the origin and expression of these works to the pliability and elasticity of lead sheets. Earlier suggestions of depth had already appeared in the background of the cast stone Stations of the Cross, the relief figures suspended in a three-dimensional space, by the artist. In these new reliefs, the sculptor developed the idea conceptually, lead materials permitting him to unfold more creatively the illusion of space. Thus, compositions like The Prophet and The Crucifixion possess a unique conception of a multidimensional background. The artist himself described the significance of this "soft" material for his work: "Lead is a very alive and endlessly generous material. It permits me to express myself directly, without modeling, casting in plaster, or having to transfer the work into some other permanent material. All this is done away with. In using lead, all vestiges of work progress remain."4

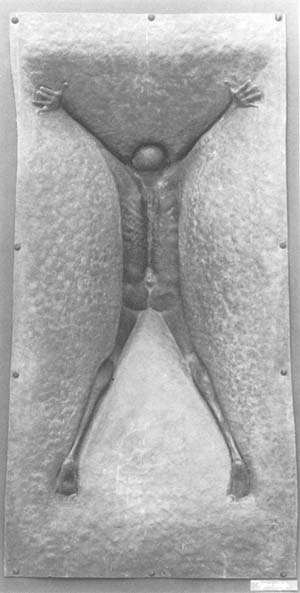

The most prominent expression of his creative discoveries is found in reliefs where tragic figures either "drown" in background space or try to break out of it. The malleability of lead under the hammer's blows allowed the sculptor to observe that "the background, rising, moving, falling, needed to be incorporated into the composition. Thus I expended as much work on the background as on the figure."5

Thus, "the background" began to express the many contradictory, circumstantial conditions of the individual in an ever-changing environment, the individual's efforts clashing against the surrounding forces. The struggle is depicted through the extraordinary tension between figure and space, in dramatic, even tragic intersections of form. In these works, the figures are struggling in and resisting space/background, this malleable, incarcerating substance appearing to both lift and consume them. In some areas, a quivering surface is illuminated by the shimmer of a gentle light; elsewhere the rough textures awaken impressions of danger and pain.

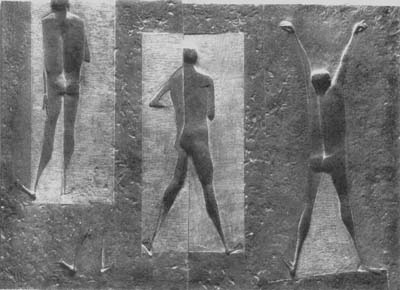

The second active character in these works is the human figure. Its treatment is plain and symbolic, often constituting a genderless person, not so much a physical as a metaphysical being. Anatomy has no meaning here, as everything is subordinated to expression. The sculptor, however, does not relinquish or avoid certain realistic elements of the body, no matter how much he simplifies the human shape. The laconic and almost bodiless figures have feet, palms of the hands and other parts of the body modeled in particular detail, which jut out into space. These different comparisons of two differing principles - abstract form enhanced with naturalistic details provide unexpected emotional suggestions.

A great part is performed, within this anatomical structure of figures, by varying points of spatial illusion - strange totally flat, indented and jutting out into space, three-dimensional joints of the body parts. Among these Boy in Space (1970) or the huge Figure in Space (1973). The human form in motion, the deeply concave trunks and convex heads, the arms and legs tossed into space - all present unexpected contrasts between the positive and negative forms.

Possibly the richest work, filled with a multitude of angles, is the above-mentioned two-meter-high Figure in Space, in which the figure looks as if it were being tossed into a hole by some tragic, dynamic event. The expressive tension is underlined by the sunken backbone, the sharp rib cage, the thrown-back head, as if from the deepest perspective point, the hips, a great force had hurled the entire figure. Janus-like, the figure appears one way from the front and totally differently from the side. This work cannot be brought into one point of vision, as each view is filled with unexpected, changing optical effects.

Within these works, the sculptor in masterly fashion controls and transforms the body through the logic of the relationship between space and figure. Though distorted, the figure does not lose its concreteness, but finds its way into the sphere of art symbolism.

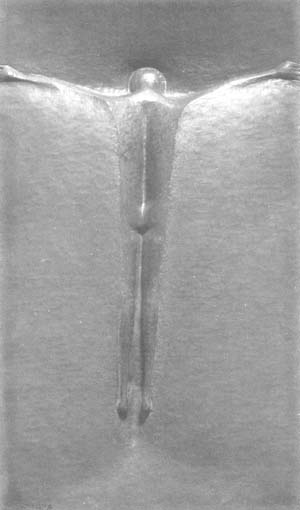

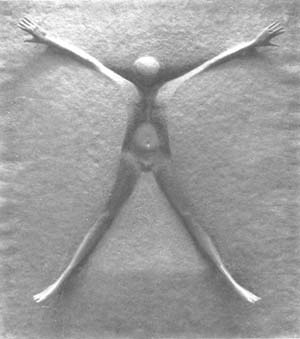

The composition in most of these reliefs features the archetypal scheme of the cross, as if these figures were being crucified. Boy in Space, Figure in Space, Nameless (1960), Figure No. 4 (1971), Figure with Stand (1971), and Flying Figure (1972) are characterized by this schematic.

Yet another sculpturally expressive structural characteristic of these works shows up in the back of the reliefs, in which the dynamics invert, and the figures strain forward toward a distant space. The implied infinity of that space is often transmitted through a means characteristic of the sculptor: the use of flat triangular or quadrangular planes to accentuate the depth of a perspective. In some places, they spill over like shafts of light; in others they depict geometric contours (Nameless, Leap, Flying Figure).

The struggling figures in the reliefs confront external and internal forces that squeeze them into tight, enclosing spaces (Figure No. 4, Figure with Stand). In others, the figures are weighed down or trapped in crypts, reminiscent of the existential vision of Putinas, a metaphor of coercion and suppression:

When I was at death's door

Exhausted and frail,

They put me away

So that my spirit would break

And I would never awake.

But disobediently

I rose from the grave!**

"Meaning may only be discovered in thoughts about death in the name of something," Albert Camus wrote in his notebook.6

One should note that within this uneven contest for existence, Vytautas Kašuba portrays the human figures as struggling and resisting, making immense efforts to free themselves. Kašuba's figures, with arms spread out like wings and feet firmly implanted find support only within themselves, becoming artistic metaphors expressed in maximal tension of form. Even an apparently weak being, so totally sapped as if sunken to the depth of a grave (Figure with Stand), is portrayed by the sculptor not as static, but in movement, its enlarged palms grabbing hold of the rim of the precipice.

One could see these figures as the Sisyphus-like relentless revolutionaries of Camus. They stand on the threshold between hope and hopelessness, existence and nonexistence, experiencing both quest and disillusionment, meaning and absurdity. This somber, sorrow-filled human world created by the artist asserts a tragic consciousness and spiritual tenacity, bringing out the unparalleled value of existential resistance, conditioned by an individual's moral dignity and inner freedom. This is a new and one of the most transcendental and philosophical stages on Kašuba's work. In analyzing the nature of vitality and creativity of being and the eternal dilemma of human choice the sculptor sheds a light of tragic nobility upon his heroes.

Kašuba recounts that these austere works appear to intimidate many viewers, but appear more accessible to individuals educated in sculptural trends. Consequently, a number of these works have found their way into private collections. Figure No. 4 was acquired by the US Embassy in Tokyo, where the sculptor participated in a group exhibit of American sculptors.

Originality of philosophical thought and a poetic plasticity of form render these reliefs masterpieces of modern art. Their conceptual and spiritual expression reveal Man as a participant in the great mystery of life. These lonely figures take their place within a universal context as a distinctive phase of existentialism and a bold breakthrough in expressionist art. As Herbert Read describes it: "Expressionism, briefly, may be defined as a form of art that gives primacy to the artist's emotional reactions to experience. The artist tries to depict, not the objective reality of the world, but the subjective reality of the feelings which objects and events arouse in his psyche, or self. It is an art that cares very little for conventional notions of beauty; it can be impressively tragic, and sometimes excessively neurotic or sentimental. But it is never merely pretty, never intellectually sterile."7

Figure in space, 1973, 218 x 80 x 31 cm, hammered lead

Girl with raised hands, 1971, 53 x 30 x 7 cm, hammered lead

Flying figure, 1972, 48 x 29 x 9 cm, hammered lead

Boy in space, 1970, 96 x 90 x 15 cm, hammered lead

Figure through aperture, 1971, 45 x 34 x 7 cm, hammered lead

Three Figures. Men. 1976-1988, 43 x 58 x 5 cm., Carved cast stone

*Excerpted from Irena Kostkevičiūtė's Vytautas Kašuba. The Human Figure in the Work of Vytautas

Kašuba (Vilnius: Regnum, 1997). Translated by Rita Frank and Andrée Pagès.

**

Translated by Lionginas Pažūsis.

1 Jung, C.G., "Ulysses", A Monologue. Volume 15 of the Collected Works (Princeton, 1966), p. 117.

2 From the author's conversation with the sculptor. New York, March 17, 1989.

3 Kašuba, V. Reply to questionnaire. 1977, Artist's personal archives.

4 From the author's conversation with the sculptor, ibid.

5 Kašuba, V. "Artist's questionnaire." Darbininkas, (Brooklyn), October 27, 1972.

6 Camus, A., From Notebook I, (Vilnius, 1993), p. 138.

7 Read, H., The Philosophy of Modern Art (London, 1957), p. 56.