Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

Copyright © 2000 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 46, No.1 - Spring 2000

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 2000 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

UNDER A GOLDEN BRIDGE

From The Lost Wax Process, a novel in progress

ANTANAS ŠILEIKA

Paris, Spring 1926

The tramps huddled around the small fire under the bridge, and Tomas huddled with them, repulsed by the stink of unwashed bodies, but grateful for their warmth. Some of the men were veterans, still broken eight years after the armistice. The rest of the men were like him, refugees from out of Eastern Europe: Russians, Lithuanians, Romanians, and a dozen other new nationalities from shattered empires. Whether French or foreign, none of the cold, sullen men under the bridge had ever heard of the Jazz Age, and if anyone had told them of it, they would not have believed a word.

It was raining out beyond the shelter of the bridge, the light, perpetual drizzle of a Parisian spring. If it rained much longer, the Seine would rise over its banks and flood the quays where the men sought shelter beneath the bridges. Left bank or right, it was all the same if the flood came.

Tomas wore the suit and coat he had not taken off since he arrived in Paris three weeks before. At his side was a valise with his wood-carving tools, with which he hoped to make a living, and a few other belongings. He had walked form Berlin after his money ran out, begging bread and potatoes along the way. It had not been easy, but by the standards of the other men under the bridge, he was a virtual gentleman. He was young and his clothes were still good. There was still some distance he could sink.

It would be unwise to go out into the rain, but evening was coming and he had to try to see the woman again.

Tomas took the leather bag in his hand, turned up the collar of his coat, and stepped out into the drizzle. His route led west, along the Rue St. Antoine to where the street became more fashionable and changed to the Rue de Rivoli, and then north up the Boulevard de Sebastopol. He had not gone far before the puddled water started to come in through his shoes. Damn! His farm childhood had taught him that wet feet or drafts killed more people than any war. But how was a man without a home to stay dry?

The traffic was more congested on the Rue Richter, and it was positively frozen in front of the great music hall, the Folies Bergère, where the cars of those who had been dropped off faced off with the cars of those arriving late. The marquee read "La Folie du Jour" and the name of the Black American dance sensation, Josephine Baker, was prominent below. Tomas had fallen in love with her in Berlin only weeks before, but he had never imagined she would become famous in those weeks. At the very first Parisian newspaper kiosk where Tomas had asked for her upon his arrival, the squat Breton with a hook where his left hand used to be, fell into a description of her charms so florid, and so voluble that Tomas could barely follow what the man said.

Tomas had not dared to try to contact her, but he had circled back again and again to the Folies Bergère. The old music hall had already been famous for decades, but it changed after the war. The prostitutes and impressionist painters were long gone. It was becoming the kind of place where a man might take his adventurous wife, although it was not yet a place where a man might take his family.

As he had before, Tomas watched the Folies Bergère from across the street, as if he could see right through the walls. What would Josephine Baker be doing? Tomas had never even seen a music hall show, but by the looks of the rushing crowd, such a show was well worth seeing. Damn, it was cold. He tramped back and forth in front of the theater. Then the street became quiet, with only the murmur of waiting chauffeurs who stepped out of their cars to smoke cigarettes and talk with one another. Tomas began to circle around the block, and off on a side street, on the Rue Saulenier, he saw that there was a side door with a small overhead light. Around this door were clustered some men. Tomas did not pay much attention at first, but as there was a great deal of time to pass before the show ended, he walked past the men several times in his round-the-block circuit. They were waiting men, like the chauffeurs. Hesitantly, Tomas made his way down towards them. No one chased him away.

Most of the men were well dressed, but a few were clearly ouvriers, working men who had changed from blue smocks to their Sunday suits.

"What are you all doing here?" Tomas asked one of the better dressed men in his bad French.

The old man who turned to respond was red in the face from the wine and brandy he had been drinking all that night. He wore a top hat and held a bouquet of flowers in his hands. "We are waiting for Josephine Baker, " he said. "After the show is over, she comes out by this door."

How ignorant he'd been. He'd always waited for her out front.

"If you are very lucky, " a young man added, "Josephine will let you go along with her when she leaves for the night."

"To do what?"

"To sing and dance in Montmartre. If you are handsome enough, or if you have a gift big enough, she will take you along for the party. She is exquisite."

The young man was not drunk, like his older companion, but intoxicated nevertheless. His hair was combed back and brilliantined.

"Pouf," said one of the working men. He had his cap set on his head at an extreme angle—the badge of a criminal or aspiring Casanova. "She is just the latest sensation. Give me a Bretonne any day. Black skin and the Charleston have turned your heads."

"A Bretonne! Fah! One of them cleans my house, " the man with the flowers said.

"Josephine Baker is the Jeanne d'Arc of the stage."

The ouvrier hooted, but the rich man had a pedantic streak in him. He defended his thesis. "No, listen. In America they were fools. Because she is a Negro woman, her talent was ignored. Paris is the only place with soil rich enough for her."

The others were listening. What else was there to do while they waited?

"Even here, Robert de Flers in Le Figaro's morning edition said she was a transatlantic exhibitionist. He claimed there was no room on the French stage for these people. You think he meant Negroes? Not at all. The right despises all Americans equally. But Josephine is rising to the top of Paris like an angel."

Josephine Baker was twenty when she came to Paris. The young Black woman, whose main trick for getting a laugh was crossing her eyes and whose favorite food was a pork chop sandwich, had brought Paris to its knees. It was a position she did not object to for her admirers. It was a position she rather enjoyed.

"How long is the show?" Tomas asked, and another man with another bouquet in his hand said that it ran over three hours.

"Your feet will be good and cold by then, my friend."

Tomas could not wait. He had been in Paris for weeks, and nothing had happened except his rejection at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, the art school. If he sat under bridges and waited, nothing would ever happen. Tomas walked to the stage door and turned the handle. The others hooted at him when they saw what he had done.

"It's not as easy as that, " one of them said. They were laughing. Tomas shifted his leather bag from his right hand to his left. When the door would not open, Tomas knocked sharply. "Now you'll catch it. Fabius, the doorman will rip off one of your ears before he throws you back."

The man who stuck his head out wore a soft cap and had a badly rolled cigarette hanging from his lip. The burning tobacco fell in bits as he talked, and the front of his blue smock was covered with tiny black flecks of burn holes.

"Salauds, " he cried, "can't you wait until the show is over?"

He would have said more, but he saw Tomas standing before him with his leather satchel in his hands.

"Are you the mechanic?" the doorman asked.

Tomas nodded.

"It's about time. Come this way."

The other men around the door began to shout their complaints, but the doorman turned on them.

"You're nothing but a bunch of mongrels. The bitches don't get out for another couple of hours. Sniff each other's asses in the meantime."

Fabius slammed the door, nodded at Tomas, and led the way, talking in a low voice all the while, explaining something. Tomas could not follow what he said, but he tried to appear as if he understood.

"This way," the doorman said, they walked along a hall, and turned into a maze of short, tight corridors. Pieces of painted scenery leaned against the walls, scenes from castles, forests, and dining halls. They passed men and women in a hurry, even a knight in armor who made no sound as he rushed down a hall. Tomas felt the armor as the man went by: wood. A mountain of colored ostrich feathers lay stacked in a recess, the red ones on the bottom, and then orange, yellow, green, and blue, as if a rainbow of birds had left behind their plumage.

"This way, " the doorman said, and now it was no longer just the sights that flew at Tomas, but the smells. There was first the mechanical smells of grease and ozone, as if an electric wire were sparking again and again. The smells were a series of layers built one upon the other. On top of the mechanical smells were those of fresh paint and shoe polish, as if from a barracks. The smell of sweat was always strong wherever people came together, so Tomas barely noticed that; it was the topmost layer that turned his head, the smell of powder, perfume, rouge and women. It became stronger as they came to an open door. The doorman barely looked in, but Tomas stopped. Inside were many women, perhaps a dozen, some seated at chairs before mirrors and very bright lights, and others standing about. All wore very tight underpants so small and flimsy that a Catholic girl could have gone to hell for daring to wear such a piece of clothing beneath a large skirt. Their breasts were bare.

Tomas had never seen such a thing in his life. He stopped to stare, and one of the women saw him. She knew that look. She stuck out her tongue. If only the priests back home had seen this, they would have vowed excommunication on anyone who even thought of going to Paris.

"This way, " the doorman said. The jaunty orchestra music and the laughter of the crowd were very close. They were right at the wings of the stage.

Tomas had acted on a whim, but as it became clear they were drawing closer to their destination, a flutter of worry went through him. the doorman had mistaken him for a mechanic. What would happen when he found out the truth?

The doorman came to a stop at the bottom of a spiral iron staircase.

"It's up there, at the top. I don't like heights. Did they tell you which motor?"

Tomas grunted, afraid to open his mouth and give himself away with his bad French. "Look for motor number three. The number is painted on the side, in yellow. Now listen, don't do anything that would interrupt the show. If you'd come this afternoon like you promised, you could have fixed it then. Now it's too late to risk anything. Just inspect the motor, and leave it alone if you're not sure you can fix it quietly and quickly without disconnecting the power. Monsieur Derval would fire me and kill you if a nut or a bolt came tumbling down during the show. If there's the least chance of things going wrong, don't do a thing up there. Wait until the show is over. We'll hope the motor holds out and you can do your repairs after the curtain."

The doorman paused and looked closely at Tomas's face. "You don't say much, do you?"

Tomas grunted.

"I told them that if they installed a German motor, no French mechanic would work on it, but nobody listens to me. There's even Germans in the audience downstairs. Eight years ago they tried to kill us, and now they're trying to buy us. Are you a German?"

Thomas shook his head.

"Probably a liar. I'd break your nose right now in the memory of my dead nephew. For all I know, it was you who stuck him with a bayonet. But the boss says we need you to fix the motor. So go ahead, but don't cause any trouble."

Tomas was relieved to scramble up the narrow metal staircase with his bag in his hand. At the top of the staircase was the first level, an iron grill floor that ran along the left side of the stage. Below him a group of women were on the stage itself. He was looking right down on the tops of their heads.

The bridge upon which he stood had no railing, and with one wrong step he would sail out and down, right onto the stage. All about him were ropes, knotted, hanging, or looped, running through pulleys and holding up curtains. He was in a forest of ropes. Along the bridge were half a dozen men intent on their jobs, knotting and unknotting ropes, pulling on rope ends, or turning crank handles. These stagehands worked quickly and silently, soft-soled espadrilles on their feet, soft caps on their heads, and sweat running down the necks of their shirts. The stagehands had to know their cues as well as the dancers down below—better—if one of them forgot or stumbled, a piece of scenery could come down right on the heads of the stage girls in ostrich feathers. Such a thing had never happened, the illusion had to be maintained. As Tomas watched them, one of the men, with a smudge of a mustache under his nose, looked over his shoulder and saw Tomas standing there.

"Go up, " he mouthed silently, and gestured up with his thumb. Tomas turned to look where the man had pointed. There was a ladder that led up even higher. Tomas climbed it. The catwalk at the top of this ladder was impossibly narrow, with no railing at all. Here were hooks in crossbeams to support curtains and backdrops, and pulleys and winches that the men controlled with ropes one level below. There were higher reaches still, where whole sets were lifted up like cards to nestle against one another in a deck hidden away from the audience. There were various motors just above his head and, out of curiosity, Tomas looked to see the numbers on the sides. Yes, and there was a number three motor attached to a girder, one of two identical motors. Tomas looked to see what they controlled, as if he really were a mechanic going about his business. The malfunctioning number three motor ran the pulley on one of the steel cables attached to a strange sphere that hung suspended by a girder that ran the width of the stage. The sphere was a prop of some kind, a giant egg covered with gilt roses and resting on its side. It had an open lid and, inside, a mirror. Tomas was half tempted to get inside the odd egg that sat open like a steamer trunk, to be a stowaway on the stage.

A ticket to the Follies Bergère, even the cheapest promenoir ticket, which gave the right to standing room down below, would have cost him more than a month's worth of food—if he had that much money to spend in the first place. But he was in luck. Now there was a chance to see a show as no one in his Lithuanian home village could ever have imagined. As for the machine he was supposed to fix, the doorman had told him not to take any chances. And he would not. He would stay where he was, and try to slip away at the end. Tomas stretched out on a girder to watch the show.

With a great movement of ropes and pulleys above and beside Tomas, a steep staircase appeared down below on the stage. The setting was a palace. At the top of the steps stood three women, who proclaimed themselves the mistresses of Louis the XIV. Why these three women, rivals for the heart of a man, should appear together so happily, and why they should all have their breasts exposed was not entirely clear. But they were certainly pretty to look at as they came down the steps and trailed long gowns behind them. When they reached the bottom, they stepped forward a little, and behind them appeared the French king himself, although it was clearly an actress playing the role of a man.

What a marvel. This was the Paris he had imagined all those years ago, not the cold and wet streets he had left outside.

Scene followed scene—coy tableaux called "Whose Handkerchief is this?" and "Oh the Pretty Sins," in which women and men made suggestive remarks or sang lewd songs to one another. Tomas could not follow the words, but the gestures were clear enough. Tomas was stretched out on the girder when he sensed that someone was climbing up the ladder to the place where he was perched. There was no time to move. A head appeared up from the ladder Tomas had used. It was Josephine Baker herself. Had she come for him? He was anxious and began to sit up to go towards her.

She walked along the girder towards him, blind to him, intent on something. She wore nothing but her slippers and a skirt of silk fringes. She stepped into the egg-shaped sphere Tomas had seen, the one covered in gilt roses. She crouched down inside and closed the lid over herself. A fanfare sounded below, and the egg began to come down from the ceiling on two pairs of cables. Down it went on well-oiled pulleys, and when it had almost touched the floor, the lid opened and Josephine was revealed to the audience. She rose up on the mirror and began her dance, an intense, jerky series of movements almost like an epileptic fit.

Tomas was fascinated. The mirror showed her legs, and to none better than him because he was up high above, but it was not her legs or the breasts that held him. There was a newness to what she was doing, a strangeness much stranger than anything he had yet seen in Paris. Was the music American or African? He did not know, for he was so raw he could not have distinguished between the rhythms of an Irving Berlin tune and African drums. It was strange. He had imagined Paris to be full of women in beautiful gowns, like those worn by the mistresses of Louis XIV, but instead he had met again this half-dressed Black woman from America. She danced with an ecstasy so intense that it was frightening. She swept aside everything that had been understood, thought, or felt before her. Tomas's excitement was filled with anxiety as well, a kind of fear. The dance ended too soon. Josephine Baker stood with her arms apart as the audience thundered. Finally, she stepped back into the egg and closed it above her. The pulleys began to turn silently, bringing her up again, and Tomas thought quickly of what he could say to her.

Tomas stood on the girder and waited as the egg rose smoothly up on its cables and the crowd continued to applaud down below. The sphere was moving slowly—it stopped for a second, and then continued jerkily on.

If the stage manager did not like interruptions, he would not like this. There would be hell to pay for the man who ran the switch for the motorized cables. It was taking impossibly long for the sphere to rise, much longer than it had to go down. Already the applause was petering out.

One side of the sphere stopped rising altogether. The cables started to hang loose on that side, but not on the other. There was a muffled shriek from inside the sphere as the cables on one side continued to rise while the ones on the other had stopped. If this kept up, the whole egg would be tipped on its side and Josephine Baker would pour out onto the stage almost thirty feet below. Already the lid was hanging open and a pair of arms grasped frantically for something to hold on to.

"Stop the cables before you kill her!" someone shouted from the wings, and the orchestra stopped playing, except for a saxophonist who blew on for two more bars before he saw what the others had seen and finally squeaked on a note before going silent. Josephine Baker climbed part way out of the egg.

"I've got nothing to hold on to in here" she shouted in English, and indeed the mirror inside was slippery and treacherous. Tomas looked above him. The number three motor that pulled the cables on one side of the egg had malfunctioned. So that's what they had been so afraid of, and that was what he was supposed to fix.

Most of the scenery was lifted by ropes, but the egg ran on greased steel cables pulled by motors newly come in from Germany. Josephine Baker was lithe and strong and could have climbed up a rope, but no person alive could climb up a greased cable. Men had run out from the wings onto the stage below, holding up their arms to catch her if she fell. More likely they would sacrifice their lives to save hers. The manager of the house, the famous Paul Derval, who had banished the prostitutes from the lobby only eight years earlier, was on the stage beside his men. Shrieks came from the audience, and twenty men who thought they knew the best thing to do called out their confusing and contradictory instructions form the wings and the orchestra pit.

"Josephine!" Tomas hissed, and she looked straight up at him.

"Get on the..." Damn. He spoke almost no English and she knew no French or German. What was the top called? "Get on the lid."

Josephine was confused by the shouting all around her, but Tomas saw no trace of fear in her eyes. She clambered onto the lid of the floating egg. This brought her a little closer to him.

Up on his girder, Tomas's eyes locked on Josephine's and he lay flat as he could and stretched forward. She was still a few feet away—too far for him to reach and too high for her to jump. Tomas sensed that there were other men around him now, men who had come up to help her, and Josephine was looking up, concentrating on the distance between them. Perhaps a yard lay between their outstretched hands.

"Get a rope!" someone shouted from nearby, right from beside his ear, and it was true that they could loop a rope and throw it down to her—perhaps even lift her up if she could not climb. There were many men around him now, and as Tomas looked into her eyes, he became desperate— for himself. She would end up all right, but what of Tomas? If someone tossed down a rope, she would be up and saved in a moment, and no thanks to him. He had to do something.

"Hold my feet, " he barked to the men who had come onto the girder beside him. He had meant to say "ankles, " but he could not remember the French word.

"Who the hell are you, anyway, and why should we take orders from you?" one of them asked.

"Hold my feet, " Tomas said with all the authority he could muster, and he guided the hands of one of the men to his ankles; the man was sure to let go in a second, so Tomas had to act quickly. Tomas leaned forward and let himself drop from the girder.

If he had enough to eat over the preceding weeks, he might have sailed right down past Josephine Baker and onto the stage below. He would have been the only man of all her admirers who had fallen so deeply and so fatally in love. As it was, the one stagehand almost lost his grip and swore quickly to the others to grab this madman's ankles, to hold Tomas suspended. Tomas had still been wearing his hat, and it came sailing straight down onto the stage below.

The tails of his coat troubled him, and he struggled with it for a moment before the sleeves slipped down over his arms and he threw the coat off and sent it down to join the hat. Tomas's upside-down face was level with hers.

"Hello, " he said in English.

"Honestly, some men will go to any lengths, " she said, and she laughed and planted a kiss on his cheek. Tomas could hear applause, and he looked out below to the audience that was standing on its feet. Buoyed by her kiss, he saluted them as if he were a circus acrobat, while the stagehands holding his legs swore deeply and pungently. Luckily, others had arrived to help hold him. Josephine Baker was an athlete who did not need to be coached. She waited until there were more men above, enough to have a solid hold on Tomas's feet, and then she grasped first his arms and then his clothing and scrambled over him, up towards the other hands on the beam above him. She was covered with sweat from the dance she had done below, and the sweat was sweet to him, her body warm as she climbed over him. Since her back was to the audience, no one could see what he did, and he kissed the bare top of her body quickly and many times as she swept over him. Then the flesh was past, and it was the silk strips of her skirt that brushed by his cheeks. Tomas felt her weight lifted off him by the arms above.

In the moment that remained before the arms above him began to pull him up, he looked out at the crowd below. All they had been able to see were his hands and his head. He gave them an upside-down salute, and the crowd broke into applause again. The orchestra started to play and someone had the presence of mind to close the curtain.

Paul Derval, the manager, shouted to Josephine from the stage below.

"I'm going to call for a doctor!"

"Why Mr. Derval, I feel just fine, " said Josephine, and she was off the girder and on her way down to the dressing rooms.

"I didn't mean for you, " Derval called up, even though she was gone. "I meant for the stagehands who fainted."

Once they had pulled Tomas up, the men on the beam slapped him on the shoulders and laughed. They shook his hand to congratulate him.

"Young man!" It was Paul Derval, still from the stage below. "Come down and see me right away."

Already workmen were rapidly hauling up the egg by hand. By the following morning, no one would be sure if it had been a near accident or just another illusion on the Folies stage. Fabius, the doorman, met him part way down.

"What's the matter with you dirty German mechanics? Why couldn't you fix the motor? Just you wait until Monsieur Derval gets a hold of you. He'll have two of the firemen beat half the life out of you, and then he'll throw you onto the street on your sabotaging ass."

Derval was waiting down below. He was bald and dressed in a black jacket, vest, and striped pants. He had a fleshy face and a great round nose, and hair combed straight back. He looked like an owner who did not take his illusions lightly.

"Who are you?"

Tomas told him his name, and then began to try to explain how it was the only idea he could think of to save Josephine Baker.

"I don't recognize you. What were you doing up there in the first place?"

"He's the German mechanic, come to fix the motor, but he is an incompetent, " the doorman offered.

"I'm not a mechanic and I'm not German. I just wanted to see the show."

"So you slipped inside?" Derval asked.

Tomas nodded. The doorman swore. For a moment, Derval said nothing. Tomas held his breath and waited.

"This is a lucky day for both you and us, " Derval finally said. Tomas let out his breath. "It would have cost me hundreds of thousands to make a change of star so soon after an opening. Come, if you want to see the show, you'll be my guest. I'll give you the best seat in the house."

The doorman was eyeing Tomas menacingly, but one look from Derval made the man drop his ugly face and put on a benign one.

"Bring him around to the producer's box, " said Derval, "but first get him some good clothes. There should be something in costumes."

For a few minutes in the back rooms of the Folies Bergère, Tomas was treated as if he were as great a star as Josephine Baker. At every turn, he received pats on the back and handshakes, and women in feather headpieces and naked breasts kissed him as they passed. He felt carried on a wave of well-wishers, into a room where a man and two women dug quickly through hanging costumes. The women seemed utterly shameless—they quickly helped him to remove his clothes—even his underclothing! He stood naked in the middle of a room with an open door, but had no time to feel abashed. He had lived on the streets for a time, so he was not clean, but they wiped his body quickly with damp towels to get off the worst of the grime. One of the women reached forward with an atomizer and sprayed him with scent across the genitals. They sat him naked in a chair and the man put a hot towel on his face. A moment later, he was shaved with a straight razor so quickly that he feared for his life. The hands flew and in minutes Tomas was dressed in the finest clothes he had ever worn, not quite formal evening wear, but nevertheless fit for an afternoon embassy party. One of the women brilliantined his hair and the other combed it back. Then he was out of the door and into a hallway, being led by an usher through the theater and into the producer's box at the front side of the stage. A bottle of champagne was sitting in a bucket and Derval was waiting inside as well. "Enjoy the show," he said. "We'll talk later."

He had gone in the time of an intermission from street tramp to guest of the manager. The illusions of the theater as laid out for the audience at the front of the stage were far more effective than the ones he had seen from above. There were no ropes and pulleys, or stagehands to distract from the effect of the deception. Here the curtain was right in front of him, and when it rose, the set went up high to give the illusion of depth, and so the scene rose vertiginously before him. Tomas had never feared heights, but there was something unsettling about looking up a staircase that seemed, through a trompe I'oeil to lead straight into a floating castle. The scenery was patently false, yet the effect so strong as to make the stage seem more real than the world outside. The painted colors were more vibrant than anything in nature, more real than nature.

First came the Tiller girls, English precision dancers who were quite beautiful in their shepherd costumes, and whose dancing reminded Tomas of many of the patterns that the farm women had danced through back home. If the dancers bore at least some resemblance to home, the music had none. He did not even know if he liked it or not. The sounds were merely alien. The acts went by quickly, almost too quickly. He wished that he had more time to drink them up. In one scene, the women were all dressed as men, in eveningwear not that dissimilar from what Tomas was wearing as he sipped on the champagne in the producer's box. Champagne! it was something like the music. He was not sure he liked it, but he enjoyed the fact of drinking it very much. It was sour and the bubbles kept getting up his nose, but it lifted his spirits remarkably quickly.

One of the women in men's wear sang, "I'm Just a Gigolo, " as the others fawned on her. It was just like it had been in Berlin—women dressed as men, yet making eyes at one another. He wanted to laugh out loud, but he was intensely aware of Derval beside him, and he did not want to look like a fool. There were comedians and jugglers, and soon one bottle of champagne was finished and a second appeared without any signal form Derval.

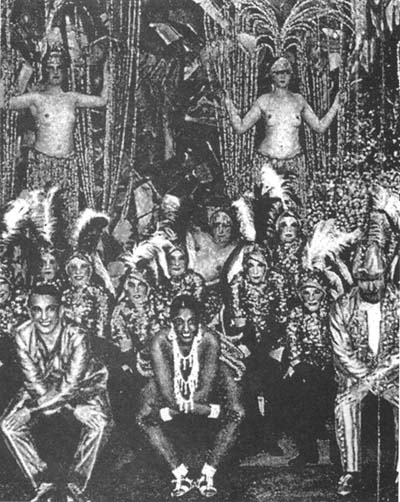

The finale of the show was called "Under a Golden Bridge, " in which the scene was all golden fountains and naked women in three tiers against a backdrop of golden mountains that had somehow found their way under a bridge. Down at the front were the stars, Dorville, Papa Bonaf and Josephine herself, dancing a Charleston. The whole picture was absurd, but all the more wonderful for it. Throughout the closing number, Tomas had eyes only for Josephine, and she lavished him with looks as well. But all too soon, the scene ended, and Tomas rose to applaud.

"There is no need to do that in here, " said Derval.

"Yes, but she's so wonderful."

"Isn't she? She'll be going back to change now. It will take her at least half an hour. We have a little time." He waited, but when Tomas volunteered nothing, he went on. "Tell me, what are you going to do next?"

Tomas turned to look at him. The question had an air of finality to it; some sort of curtain was in danger of coming down.

"I thought I'd go back to her dressing room. I met her in Berlin, you see, " and he began to blush furiously.

"And you slept with her?"

"Not exactly. We did something..."

Derval held up his hand. "Spare me the sordid details. I can imagine. I've seen more things under staircases, in toilets, and in the niches of dressing rooms than you can imagine. I once had a fireman who could not keep his hands off the boys unless it was to reach for his own hose. But let me ask you this. You will go back to see her, and maybe you will get lucky again. Who knows? I'm sure she is grateful. But what after that?"

"I think I'm in love."

Derval laughed.

"You're in love all right. You and a hundred thousand other men. Maybe even more. I certainly hope so, because then they'll come to see the show again and again. But think of all the competition you will have. Do you see what goes on at the stage door in the rue Saulenier each night? There are millionaires out there. She sleeps with all these men. Did you know that?"

"Don't talk that way abut her."

"But why not? It's true that she sleeps with whomever she pleases. Does that bother you? Do you think you would be happy even if you did become her lover, knowing that she would never love you alone?"

The theater emptied quickly. Already the men with brooms were sweeping the main aisles, and the ushers were looking under the seats for any money or jewelry that might have fallen down there. Tomas did not know what to say.

"Tell me about yourself, " said Derval, and Tomas explained how he had come to Paris to be a sculptor. He spoke of his adventures in Lithuania and Berlin. Derval nodded throughout, appreciative, but neither impressed nor dismayed. Paris was full of fantastic stories. Josephine Baker was a fantastic story herself.

"Ever since Rodin, sculptors have become great men. You have chosen wisely, my friend, " said Derval. "You could make a name for yourself if you are any good and you have a little luck. I'll tell you what. Permit me to give you a little something to get you started. Then, when you have your first show, I will come and buy something. Who knows? Maybe I'll bring along some of my acquaintances. In this line of work, I meet many people who have money. They are always trying to catch the new wave. But take my advice. Don't go down to Mademoiselle Baker's dressing room. Leave that game to the men out at the stage door."

"I don't think I could do that."

"Then think some more. The competition for her love will be fierce."

"I thinks she loves me a bit already."

Derval looked skeptical. "You come down off the ceiling to save her life. Of course she gives you an appreciative nod, but remember that she is in the business of making illusion. What you see of her on stage is not human."

"I didn't meet her on stage. I met her in a drawing room in Berlin."

"But she is a show girl now. It is like having a magnificent disease. It makes you larger than life, and it makes you utterly unsuitable for life. She will need to be admired all the time, and you will just be one of the many drones circling around her."

"I'll make you a proposition," said Tomas.

Derval looked at him, dumbfounded for a moment.

"I'm all ears."

"Don't give me any money at all. Just give me a job. I learned my sculpture through wood carving. You must need carpenters on the sets, and woodcarvers too. I can work plaster as well. That way, I would be worth something to you. You could discharge your debt that way."

"Ah yes, my debt. And what good do you think it would do me to have a star-struck carpenter walking around the stage all day? The rest of them here have seen so much skin that they go out to find women with clothes on just for the thrill. Besides, I have all the carpenters I need right now."

Is there no job I could do?"

Derval considered.

"Maybe one."

"What's that?"

"You could watch the stage door. I had Fabius fired half an hour ago."

"The man who showed me in?"

"Yes. We were lucky with you. You could have turned out to have been a criminal. But I promise you, if Miss Baker so much as frowns in your direction, you'll be out of a job."

"Oh, she won't frown," said Tomas. "She'll smile with delight every time she sees me."

Derval looked skeptical again, but he did not say no.