Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

Copyright © 2001 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 47, No. 2 - Summer 2001

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 2001 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

JUOZAS JAKŠTAS: A LITHUANIAN CARVER CONFRONTS THE VENERABLE OAK

MILDA BAKŠYS RICHARDSON

Boston University

The spirit of the Middle Ages longed to express religious feelings in bold and dramatic art. According to Johan Huizinga there was "a marked tendency of thought to embody the religious atmosphere in images."1 Every theological thought or conception resolved itself visually; all religious emotions took on a concrete form. In modern Lithuania, this unfolding of medieval faith and deeply religious culture is embodied in the powerful woodcarving of Juozas Jakštas,2 with its strong reliance on narrative. His art not only stimulates religious consciousness, but also challenges the pride and profanity of modern political systems that reject spiritual consciousness by reducing the infinite to the finite and disintegrating all mystery in life.

The art of the carver Jakštas visually compels the viewer to stop and respond to the plight of a people forcibly deprived of their religion and culture and desperately struggling to survive the process of "mankur-tization"3, with its aggressive trameling of national memory. As a dissident and political activist, Jakštas has endured relentless harassment by the authorities, a situation which has made it difficult for scholars to focus on his creative works.4

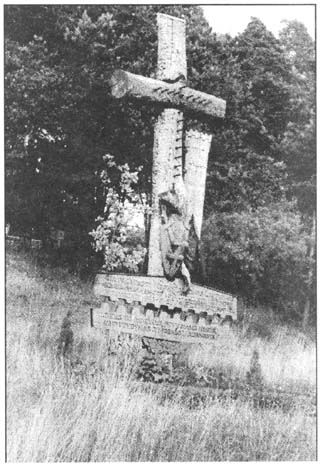

However, most visitors to the Hill of Crosses pilgrimage site near Šiauliai are already familiar with one of his monumental wayside shrines, the Great Cross, which stands to the right of the main stepped path over the hill (Fig. 1), Jakštas periodically erected monuments honoring Catholic human rights activists, and one of his earliest gravemarkers was erected in 1978 in the Ceikiniai cemetery of the Ignalina region for the priest Karolis Garuckas, who had been a member of the Helsinki Watch Committee formed in 1976a Latin cross with aureole placed under a roof decorated with carved stylized waves. The dove of the Holy Ghost with spread wings is carved on the horizontal arm. This same dove motif also appears on the Great Cross, which is composed of three dominant elements, each carved directly from one of the oak trunk's three branches, so that they appear to emerge from the earth itself: on the right, a Latin cross with an aureole and the Holy Ghost under a roof resting on the three arms. Given Jakštas's penchant for multivocal symbolism, it is conceivable that the dove image represents not only the spirit of God as mentioned in Matthew 3:16, but also the folk belief in the purity of souls, and in these carvings, possibly the abstract concept of the soul of defiled Lithuania and its immanent reincarnation through political liberation. The vertical element of the cross, nine meters in height, is progressively flattened and refined toward the top, and its form repeated above in the delicate wrought iron ornament with its filigree curls. To the left is a shorter traditional roofed pole decorated with wood carvings on 1:he upper sides. Together with its bolder wrought iron member, emphasizing sun and moon motifs, the pole fits snugly beside the loftier cross. From the third branch, at the crotch of the tree trunk, Jakštas carved a robed figure of the Contemplative Christ under a plain chapel roof. The head of Christ is covered with a disproportionately large crown of thorns, thus drawing attention to his austere and noble face, characteristic of the type produced by Jakštas. Pedestrians meet the meditative figure of Christ at eye level and are immediately drawn into an intimate and silent spiritual dialogue.

1. Great Cross, 1981, detail of oak and wrought iron ensemble. Meškučiai Castle Hill (Hill of Crosses), Šiauliai.

Every cross is brought voluntarily to the hill as a kind of pilgrimage with a special purposeto perform a vow or penance, to obtain a divine blessing, or to commemorate an event.5 The hill has been a pilgrimage site and locus of communitas since the mid-nineteenth century and continues to serve as a central icon of Lithuanian national identity, illustrating Victor Turner's thesis that, "Pilgrimages are, in a way, both instruments and indicators of a sort of mystical regionalism as well as a mystical nationalism."6 Before Father Garuckas passed away, he asked Jakštas to erect a cross such as Lithuania had not yet seen on the site and in it to express the depth of the nation's suffering. He added that should the task prove too difficult for Jakštas, he would come to him as a priest through prayer. Over the next few years, Jakštas's son, Juozukas, suffered several accidents. He fell from a church organ loft, but escaped injury. His father accidentally drove a wagonload of potatoes over his foot, but the boy was unharmed. On another occasion, a vehicle skidded toward the boy standing nearby, but stopped within inches of him. In 1981, Juozukas was diagnosed with meningitis. Anxious, but never losing faith, the family went to Father Garuckas's grave to pray. Acutely aware that he had not yet fulfilled his promise to his friend, Jakštas prayed for his son's life and vowed to erect a cross. Shortly thereafter, the boy regained consciousness and fully recovered. Jakštas immediately started carving the triple forked oak and erected it on the hill just prior to known plan to once again bulldoze the shrine.7 The authorities visited the hill and saw the newly created Great Cross, but decided against razing it, since there were already several religious festivals being planned at other sites, such as Šiluva,8 and they feared their actions might incite the crowds. Local folklore avers that the Great Cross saved the hill from further demolition.

Thus this harmonious, imposing ensemble visited and appreciated by thousands of people each year, contains a multitude of meanings: personal intentions, prayers of intercession, ties to a folk art tradition, grief for a suffering nation, resistance to tyranny, hope for the future. In the craftsman's words, "The Lithuanian earth grew this oak as if it were an embodiment of the cross... Before chopping down a tree, I say a prayer and ask help of the souls of all those who grew it and nurtured it. There is divinity in a tree. A tree raised and held Jesus Christ, the tree quietly and patiently suffered together with Him. Perhaps that is why I can easily cope with the largest of the mighty oaks. For in them there is more life and wisdom, more sun and sky, as well as divine power." In this spontaneous quotation, Jakštas connects the oak tree with autochthonous reality and the Lithuanian uniqueness of its origin. Not unlike the ancient Druids, he anticipates the potency of the cross form in the tree itself, harvesting the tree becomes a prayerful ritual of connection with the silent ghosts of ancestors who invoke the sacred oak's power. Jakštas explains his respect for the material itself his wish to emphasize an awareness of its original state while anticipating the artistic statement it will make. The artist continues with an understated description of Christ's passion on the via crucis and the role of the oak in His life, death and resurrection. This narrative of hope and divine grace, he says, gives him the extraordinary strength to handle the "mighty oaks"always masculine trees in mythological imagination.

When the organizers of a memorial for the 125th anniversary of the 1863 uprising against the Russian Czar9 gathered small oaks for a wayside shrine ensemble on a collective farm in Dubičiai, Jakštas immediately envisioned a carving that would be innovative and depart in a significant way from the wayside shrine tradition. He called for a large oak, which the organizers reluctantly provided, even though they felt the idea Jakštas proposed was too bold and politically inflammatory for the tense period in 1988 just prior to independence. Finally, an appropriately large oak was delivered, and Jakštas spent five days carving Though the battle is lost, there is no defeat. The figure of the insurrectionist is at ground level, depicted fallen on one knee, head bowed in despair. Jakštas has transformed the Contemplative Christ figure, which shows Christ resting his head on his right arm, into a secular figure of a man covering his eyes with his right hand as a physical response to a tragic vision too horrendous to witness.10 Above the chapel protecting the figure rises a massive totem with powerful imagery. At the end of a stone path leading through a Siberian pine forest, the image quickly becomes intensified. The heavy boots of an allegorical Czarist soldier stomp thorough a deep pile of fragile human skulls as the cracking bones shatter the stillness of the forest. Exaggerated chains crisscross the soldier's skeleton above and, in place of a heart, a tocsin tolls for the perpetual battle and suffering. Enormous epauletsreminiscent of insignia seen on military memorials of the period Czarist uniformappear on either side of a collarbone. The vertebrae of the neck stretch several feet highbringing to mind the canonical image of the skeletal figure of deathand hold a crown with an imperial double eagle. The image of boots crushing the skulls of the dead reminds us of the gratuitous degradation and cruelty of war. Yet this image of power over the powerless, of violence against the defenseless is pitted against another equally strong image. The figure above the boots, in spite of its clenched fists and oversized epaulets, is only a bare skeleton in chains of bondage. Or are they chains of conscience and guilt? Has his free will been taken hostage? Is the figure chained to the destiny of autocratic rule? Does the bell toll for the suffering of all mankind or does it ring out as a call to a conscience encircled by evil and deaf to morality? On balance and with these questions unanswered, an intriguing possibility exists that this faceless and skeletal figure is performing a kind of medieval and macabre dance of death. As he looks down at the skulls, he sees himself in the form of his deathly double.

The art of visionary folk artists like Jakštas is a lens through which we can glimpse the interior world in which he creates, "...the concealed imaginative world of the artist, a sea that is largely uncharted."11 Jakštas conjures up images as if in a dream, he combines images from reality, his own unconscious, literary references, history, mythology and, most importantly, religion. Visionary artists are often possessed by an image and they release its spirit into the material they are working on. As Jakštas carves his oak trunks and intuitively brings into view the images of his imagination, in a certain way he exorcises himself of the dream. Jakštas's religious and political symbolism is readily accessible to his East European viewers because of their shared culture. To an outsider who has not experienced the "agony of nations" or the situation of captive nations under communism, with its atrocities and loss of liberty, the imagery may not appear as painful, yet it is so straightforward that one immediately feels empathy with the desperate insurrectionist. For Jakštas, the process of carving is an act of communication that moves from the carver through his work and finally out to the spectator as participant. When the memorial project was finished, his fellow carvers, with fear in their hearts for Jakštas's bold statement, wept out of a sense of historical consciousness and a pandemic recognition of the symbolic universality of the dramatic imagery.

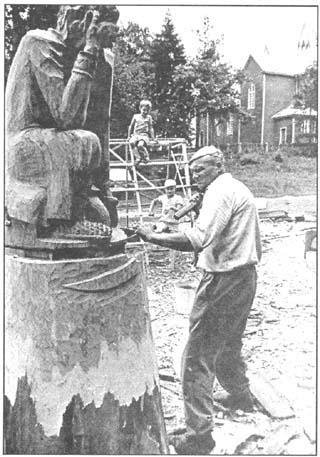

Jakštas does not like to be observed while carving only the sound of children playing does not disturb his inspired concentration. If one is fortunate to watch him carve (Figure 2), one is immediately struck by the tremendous intensity with which he works. This intensity of feeling has driven him to express himself in wood carving since childhood. As one of seven children on a farm in the village of Jukiškės, Jakštas, born in 1940, worked hard tending the livestock while longing for a carving knife and a set of paints. Out of desperation, he once traded his father's bicycle for a carving knife and remembers being severely punished that night. He learned the construction trade at the Vilnius Technical School, where his favorite classes were drafting and architectural history. Following three years in the Soviet Army, he took courses at Vilnius University. While in Vilnius, he was deeply influenced by the religious art of the Gothic and Baroque churches that he visited frequently. Due to financial constraints, he gave up his longing for an art education and spent the next twenty years in construction, where as a fireman he experienced all the frustrations of trying to improve working conditions for his crew. After spending three years organizing a project to reform regional construction standards, by 1978, at the age of 38, he had become an outspoken dissident and actively collaborated with the Helsinki Human Rights Committee. His political activism was the genesis of his folk art creativity in the early 1980s. His carvings reach to the depths of human spirituality, and one senses that the emotions, faith, ideals and dreams portrayed in them had been so long repressed that he could never complete enough carvings to express them adequately in their plenitude.

2. Juozas Jakštas carving the figure for Though the Battle Is Lost There Is No Defeat, 1988.

Typically, Jakštas searched for several days to find just the right oak to realize his concept for the wayside shrine ensemble planned to accompany the proclamation by the United National General Assembly that 1986 be declared a Year of Peace. He and a group of artisans representing three generations of members of the Folk Art Society,12 in cooperation with the Ministry of Culture, gathered at Šalčininkėliai in southeast Lithuania to discuss the chosen theme: the meaning of the good life as expressed in folk songs about farm work, rising a family, participation in the community and hopes for the future during times of peace and prosperity, and the disruption of the. peaceful cycles by war and the loss of fathers and sons.13

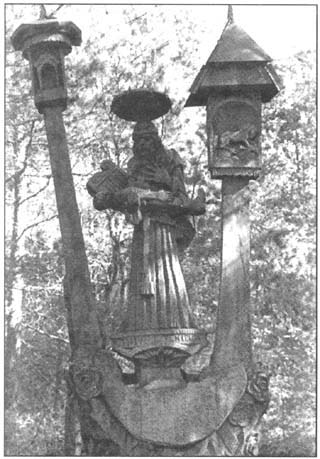

As Jakštas began chopping at an old twin-branched charred log, he revealed spent rifle cartridges in its heart and embraced the oak when he realized it had been an unwilling witness to a tragic event. Jakštas incorporated the sense of tragedy in his carving by utilizing the twin branches and placing a shrine on the end of each (Figure 3, detail). In the crotch of the tree stands the mythological singer Dainius, influenced by ecclesiastical sculptures Jakštas had seen of King David with his lyre. Although, instead of a crown, there is a halo-like roof to protect the figure from rain.14 In his right arm, Dainius carries a dead warrior, a small, stiff figure wearing boots. He presses his hand against his thick beard and chest as he sings a song of lament for the fallen rider, meant to symbolize all patriots. In the chapel on the right is carved a steed, fallen to its knees, while the chapel on the left is empty, as if to suggest that the protective saint invoked by the passerby was absent at this moment, evoking the thoughts of desperate people that God has forsaken them during times of war. The inscriptions are from the folk lament, "Kur kuns gulėjorožės žydėjo, Kur galva kritoten rūtos dygo." ["Where a body layroses bloomed; where a head fell, there sprouted rue."]15 The base of the oak is carved with a saddle, stirrups and vines of roses. Jakštas imagined Dainius as emerging from the hollow of the tree, standing high above the implements of battle to proclaim peace. Perhaps Jakštas was delving into an ancient legend that told of the healing power released to a man crawling through the cavity of an oak tree.16 This carving, set in a small clearing amidst birch trees, is one that Jakštas frequently returns to in his mind. Again, some of his colleagues thought it was too bold, its height alone of five meters dwarfing all the others. In vindication of his efforts, Jakštas and several other craftsmen were awarded the 1986 folk art prize by the Ministry of Culture.

3. Dainius, 1986, detail of upper portion of oak carving. Šalčininkėliai, Šalčininkai district. Dedicated to United Nations Year of Peace.

The disruption of peaceful life by war is a recurring theme in Jakstas's work. In an ensemble of three carvings to honor partisan fighters, erected in a field by the village of Peršaukštis in 1982, the first totem depicts partisans returning from the guerrilla warfare of the forests to a life of peaceful normalcy. The second totem depicts birds flying out of the ancient forests as well, as if to signify that their natural habitat has been defiled and war has driven them from the breast of eternal nature. The third reflects the agrarian state of productivitythe true nature of Lithuanian life and prosperity. Visualized is a panorama of a wheat field and a man carrying a scythe with cornflowers blossoming above.

In Jakštas's mind, war is not the only thing that disrupts life and creates imbalance. His instinctive hostility to the industrialization, collectivization and mindless modernization imposed by the Soviet government is ruefully expressed in a pictorial mode on a series of seven has reliefs carved in oak. Each is divided into two scenes, on the left the primeval and pastoral landscapes that once existed, on the right, the destruction and desecration of Lithuania's natural beauty by the political regime. A maiden in folk costume walking serenely through a field of wildflowers is juxtaposed to a female collective farm worker wearing pants and operating a combine harvester. A solitary chamomile blossom curves gently over the bank of a river, while on the other bank a companion blossom has flat, pointed petals, and is pollenless, offering nothing to the bees whose honeycombs remain empty. A scene of orchards, a barefoot plowman and birds feeding their nestlings opposes the bland landscape on the right, with its empty bird's nest an collective farms and factories. In the final relief, churches symbolizing wisdom and spirituality on the left contrast with television towers on the right, erected to carry soulless messages and "information." The series, frequently submitted for exhibition and consistently rejected by authorities as too reactionary, is displayed in the Jakštas's farmhouse. As an iconophile, Jakštas affirms with these reliefs the need for a visible embodiment of the social drama being played out on the stage of the Lithuanian landscape. The person witnessing this drama is an imaginary pilgrim faced with two contrasting models of communityone autochthonous, traditional and historical; the other artificial, secular, alien and transient.

Jakštas uses his carving technique to search for answers to the mystery of the human dilemma in the oak sculptures he creates, but feels that he has learned little.

He insists that he understands nothing, but is driven to visually represent his concepts of Good and Evil. For the en-seinble set in the pine forest covering the hills of the Kuršiai Lagoon of the Baltic Sea, known as the Hill of Witches, he joined a group of skilled master craftsmen who had been participating in Folk Art Society seminars for a decade.17 For the first time, Jakštas expressed open anger at the political system and frustration with his people. The early 1980s was a period when expressions of resistance to the promises and pressures of Communism were beginning to foment, and Jakštas felt the time was ripe to visually express his idea of resistance to a failing socialism.18 He created an allegory based on the legend of the Death of Neringa. When Neringa, one of the daughters of Adam and Eve, went out into the world looking for a place to live, she discovered the shore of the Baltic Sea and settled in a place as beautiful and idyllic as the Garden of Eden. She and her family invited all their relatives to visit. The relatives became very jealous and returned to their homes to prepare for war to usurp this perfect place. Neringa, wanting to protect her new homeland from the warring tribes to the west, planted dense forests of oak. To the east she carried sand from the Baltic coast in her apron and kept emptying it until she formed a barrier, a peninsula known as Neringa, which with its vast sand dunes shelters the Kuršiai Lagoon from the Baltic Sea to this day. The beautiful Neringa herself was swept up by a storm and lost at sea.

Jakštas's interpretation of the legend is an ensemble (Fig. 4) that combines a vertical totem flanked by two horizontal logs at its base. The monster figure represents evil, which at first dominates good. The horizontal members depict mermaids with long, beautiful flowing hair, which evokes the waves of the sea. The monster does not acknowledge the beauty of these creatures, but opens his jaws to swallow Neringa herself, whose face is turned away as if unaware of her horrible fate. According to Jakštas, the monster represents everything that is evil about the political-economic system, especially the destruction of the once pristine environment by the storage tanks, machines, and giant factories built as barrier zones to the sea. The innocent maiden is, of course, his beloved Lithuania. The passivity of the people is reflected in the calm faces of the mermaids who splash about, paying no heed.

4. Death of Neringa, 1981, oak. Hill of witches (Raganų kalnas), Juodkrantė.

In defiance of restraint, Jakštas had intended to carve the nose of the monster in the form of a huge sword about to plunge into the heart of the innocent maiden. However, his fellow folk artists persuaded him to mollify the imagery. The remains of the sword handle can still be seen in the forehead of the monster, which was recarved to look simply deeply furrowed. The seminar organizers refused to supply Jakštas with appropriate oaks for this work, so he himself found several ash instead and poured all his righteous anger into the massive trunks. Recently, the ensemble was mysteriously torched and has been replaced by a single carving of a more benign and neutral creature, with horns about to swallow the hapless Neringa.

The imagery in the Neringa and Though the Battle is Lost... carvings parallels the use of metaphor by the architect Antonio Gaudi on the facade of Case Batllo in Barcelona (1904-6). The lower two floors are articulated by carvings of bones and lava. The central portion of the facade is covered by a scene with an undulating sea and death masks. A phlegmatic dragon looks down from the roof. According to Charles Jencks, an interpreter of postmodern architectural meanings, the "building represents Barcelona's separatist hopes: her Patron Saint, St. George, kills the dragon of Spain who has eaten up the Catalan peoplethe bones and skeletons remain as monuments to the martyrs."19 Jencks offers the facade of the building as an example of extreme anthropomorphic imagery. The works sharenot identically, but with some notable resemblancesa politically charged iconography employed as a powerful tool in rendering the reactions to a political crisis by a people whose passions for resistance are ignited. What we see in Jakštas's manner of presentation is a directness of visual impact that is so characteristic of medieval art.

Jakštas does not devote his inexhaustible creativity exclusively to political and social causes. His role as teacher and mediator of Christian values is an integral part of his commitment to the community. Nowhere is this spiritual pledge more intensely fulfilled than in his work with local children and his intrepid dedication to freeing their young minds and hearts from the mundane and profane structures of modern society. Jakštas reveals his desire to propagate the faith by teaching Bible stories to children in the village school of the Reškutėnų parish, where he himself was raised. At the "Gandriukas" [The Little Stork] kindergarten in Švenčioniai, he created a sculpture ensemble known unofficially as Bethlehem. Using Aesopic allegory as protective evasion, he teaches a religious story by disguising it as an animal fable. An infant is asleep in a village hut under a roof covered with strawin other words, the Christ Child asleep in the manger. Instead of the usual animals coming to visit him, little rabbits encircle the sleeping child. Suddenly, a wolf appears. In order to prevent the wolf from attacking the child, the rabbits nail his tail to the ground. Under an evergreen, a rabbit scolds the wolf, telling him to be quiet and stop howling so that the sleeping child will not awaken. The birth of the child is announced by a stork on the roof. The charming carvings are laden with symbolism and metaphoric lessons about the power of faith and the means adults use to teach their children stories that illustrate the Christian message.

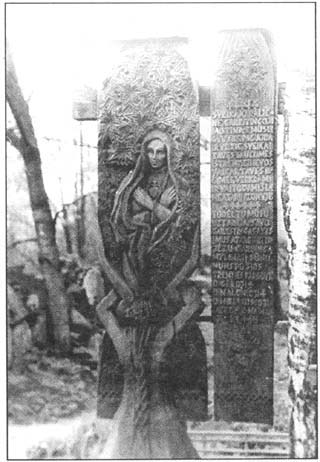

Jakštas's gentleness with children becomes even more compassion when dealing with memorials to women. When folk artist Irena Janovič died in 1985, her family and friends hesitated to erect a cross on her grave, even though she had been an activist for religious freedom, as well as a noted church mural painter. Jakštas's solution (Fig. 5) for her grave marker was to portray her soul returning to visit her place of final rest in the land she loved so much. The figure of the deceased woman is shown from the back, embracing the knees of the redemptive Madonna beside a prayer of intercession to the mother of God, as well as the patroness of Lithuania. The intertwining of the two figures forms a pattern that is repeated in the young woman's braid and in the abstract weaving on the background. The artist's paint brushes are carved at the bottom to immortalize her contribution to Christian art.

5. Irena Janovič, 1985, detail of oak gravemarker. Kliusčioniai Village Cemetery, Belarus (formerly Byelorussian Soviet socialist Republic).

Ancient Lithuanian belief held that certain trees were sacred because the souls of the dead lived in them.20 These folk beliefs are an integral part of Lithuanian cultural heritage and, like many people, Jakštas combines them with Christian teachings. In 1989, he visualized the soul of a Siberian mother, as transfigured into a cedar, in a slender totem (Fig. 6detail) twenty meters high, so precariously balanced it had to be reinforced by railroad tracks. The totem stands near the railroad station in Ignalina at the far eastern territory of Lithuania, and the railroad tracks are used to symbolize the mass deportations of Lithuanians to Siberia by train. This mother's children were also deported to Siberia. They are cold and hungry and are begging for food. What can the mother's soul do? She lowers her hand, transformed into a branch, and holds out a handful of pine cones to her children. The poignancy of this simple gesture reminds us of the sacrifices of many adults who deprived themselves of food in order to save children.21 In a call to faith, with her other hand, the mother holds up a crucifix to the sky. Christ glances down at the dying mother, as if to say, "Daughter, be of good comfort; thy faith hath made thee whole" (Matthew 9:22). The image of hope evoked in the raised crucifix echoes another passage, "Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted" (Matthew 5:4). The inscription on the totem itself reads, "Per Sibiro kančią į prisikėlimą." ["Through the suffering of Siberia to resurrection."] In Jakštas's conservative and mystical theology, the surest path to salvation is innocent suffering.

Jakštas is a man of and for his times. He is a stern prophet of contemporary life and its spiritual aridity and the occluded political philosophy. But he is also a profound commentator on history in its tragic and hopeful manifestations.22 Out of Jakštas's historical sensibilities comes the powerful application of his art as a mnemonic device. Remembrance is a recreation of the historical event and a way of connecting martyrs from the past with the living community.

6. Siberian Mother, 1989, detail of oak carving supported by railroad tracks. Ignalina.

During a road building project between Švenčioniai and Cirkliškiai, the remains of a large group of people were uncovered, of whom the names of 83 have been confirmed. It was a burial place for anti-Soviet resistance fighters following World War II. The people decided to erect a monument along the edge of the Labanorių forest and planted 83 oak trees on the gently sloping terrain. In addition, they erected a metal cross lying on its side to evoke the weapons of subjugation of the 1940 occupation. Nearby, Jakštas built a large wayside chapel with a life-size Contemplative Christ. Below are carved the defiant words, "Kas žūva už laisvęnežuvę." [Those who have died for freedom have not perished.]

In honor of the Jewish people who were persecuted during the Nazi occupation from 1941 to 1944, Jakštas designed a monument that unites the menorah with natural tree roots rising from a Star of David pattern on the groundclaiming its place on Lithuanian soil. This giant oak carving stands in the center of the town green in Švenčioniai.

In the Švenčioniai cemetery a monument (Fig. 7) commemorating military officers killed during the Soviet occupation in 1941 was erected on the site of a nineteenth century chapel that had been built in memory of those who died in the 1963 uprising. The chapel had been torn down by Soviet authorities in 1965. The protruding nails of the simple cross made of two oak branches evoke pain and the passion of the crucified Christ. The board below, which resembles a torture instrument with teeth, carries an inscription which reads, "...Didesnio paminklo didvyriams nebus kaip vykdymas jų idealo." [There is no greater monument for heroes than the realization of their ideals."] These words already resonated in 1989, the year before independence was declared.

Although he can never forget or forgive the brutalities suffered by so many of his countrymen, Jakštas's faith remains deep and enduring. His carvings in celebration of the power of faith are, perhaps, the most stirring. In a monument to mark the tenth anniversary (1973-83) of the clandestine Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania,23 Jakštas depicted a book in the form of a chapel with a flame24 rising toward the sky through a wreath of sorrows held by four severed hands, symbolizing a family. Christ is portrayed bound by a thick, twisted rope. The memorial, weighing four tons, was secretly constructed and erected in the village of Virbaliai. A few days later the local parish priest, Sigitas Tamkevičius, was arrested. He was ą dissident who had repeatedly preached the Catechism and organized a Christmas festival for the children, but was even more feared for his role as editor of the Chronicle. He was sentenced to six years in the Gulag and five more years of exile. He was, however released as the independence movement gathered strength. At the top of the shrine is a large sun with ten rays, representing the ten years of publication of the Chronicle.

7. Monument to Soldiers and Officers of the Lithuanian Army Killed by Soviets in 1941, erected in 1989, oak, Švenčioniai Cemetery.

The sculpture Candle for the Christianity jubilee was designed to honor Reverend Bronislavas Laurinavičius, a human rights activist, who was persecuted and finally assassinated. According to Jakštas, the priest was like a candle, whose single flame burned for the Rebirth Movement toward independence. The carving is in the form of a giant candle with drops of wax representing historical figures. Christian martyrs hold a shroud in their hand with the face of Christ on it. A Pieta" appears at the very bottom. The artist's intention was for Lithuanians to see the ubiquitous presence of the Savior, and that His Passion for humankind and for the nation will burn for all time.

Jakštas was the unchallenged choice to. carve several memorials to celebrate the 600th jubilee of Christianity in Lithuania in 1987. His memorial in the churchyard of Mielagėnai is entitled Cantante Domino, and Lithuania is visualized as a large relief in the shape of a castle tower. Jakštas always carves from the bottom up and, when he carves in relief, he moves his knife over the wood like a painter, covering the canvas with thick impasto. The Lord, with finely chiseled noble, classical features, holds a wreath into which are woven jewels and native flowers. Each century of Christianity is represented by a single blossom, which opens only once. The largest blossom, the seventh, is for the century to come. Below, on the wide base of the relief, members of ancient royalty kneel on mounds of amber (the "gold" of the Baltic coast), bowing to Christ.

For one of the jubilee memorials in the church yard of his home town, Švenčionėliai, Christianity itself is depicted as an ark, with its sails as six triangular chapels on roofed poles rising from the ark. In each chapel there is a Contemplative Christ and a wrought iron decoration on top appropriate for the age. Out of the center of the ark rises a tall cross, almost three times the height of the others, symbolizing the promise of the century to come. Along its vertical shaft a series of small bells rings to remind the people of their eternal hymns. The metal wreath on the central cross reminds the populace that Lithuania will never be free without vigilance and preparedness to do battle against hostile forces. The central motif of the ark symbolizes the reemergence of power to preserve and to ensure the rebirth of spiritual life when the proper conditions are created. The monument thereby unites the celebration and reaffirmation of Christianity with the emerging independence movement.

8. Christ Triumphant, 1986-87, oak. Detail of manument commemorating the 600th Jubilee of Lithuanian Christianity. Švenčioniai churchyard.

Another memorial is highly architectonicalthough it appears to be made of several pieces, it is actually a single block of oak (Fig. 8). A robed Christ is shown standing Triumphant above a niche formed by a folded patterned weaving. A small wayside shrine is carved behind a fence in the niche amidst a garden of rue flowers. A crucifix appears on the shrine, thus uniting in one monument two different images of Christ, perhaps reflecting both the Eastern and Western Christian traditions Jakštas had studied in religious illustrations. The sculpture is designed from the ground up to narrate the belief that everything that is permanent and peaceful comes thorough Baptism and suffering. On the reverse side of the sculpture are carved the words from the Gospel of St. John the Evangelist (1.1), "In the beginning was the Word..." In Lithuanian mythology the oak was the most widely worshipped tree and a symbol of endurance, strength and triumph. It was also the tree most often to be struck by lighting and, therefore, related to the worship of the pagan god Perkūnas. With the adoption of Christianity and the merging of pagan with Christian beliefs, the oak was resanctified from the pagan gods to Christ by the ritual of carving a cross on the trunk.25 In this oak sculpture, Jakštas has merged the creative forces of folk belief with Christian optimism.

The central tenet in Jakštas's highly personal philosophy is the idea of Manichean dualism and the struggle of good and evil. His carvings illustrate bold oppositions and almost mystical contradictions. His works, on the one hand, are powerful and stable, but on the other full of spirit and drama. At times they express a quiet sadness, while still asserting a life-reinforcing aspect. He never pleads for your attention, but boldly states the living truth of the Christian message as he feels it through the personal relationship with Christ he works out in his sculptural narration. Jakštas leads us into his own privateeven intimateworld of genuinely original conception. He never evades the rich complexities of cultural creationhe never submits to a single vision of the sacred as he projects human feelings into inanimate objects. For Jakštas, the Christian vision is basically sound, but needs to be articulated in new ways for a more complex world. As he reacts to this complexity, he does so as his craftsman counterparts did in the Middle Ages, by visualizing abstract theological concepts in concrete, but highly symbolic, imagery.

1 Johan Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages (New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1954): 151.

2 This essay is based on fieldwork throughout Lithuania, as well as interviews and correspondence with Juozas Jakštas over the last ten years. The period of his work covered is up to Lithuanian independence in 1990. The research project was partially supported by the Art History Department and Graduate School of Boston University. I am deeply grateful to Prof. Vacys Milius at the History Institute of the Lithuanian Academy of Arts and Sciences for introducing me to Mr. Jakštas and for his enthusiastic support of my research. My warm thanks to Prof. Jurgis Stašaitis of Vilnius University who, during a bitterly cold winter, accompanied me on productive research trips. It is impossible to adequately thank the Butvilą and Sabaliauskas families for their most generous and kind hospitality. In the United States, I benefited greatly from discussions with Prof. Margaret Yocom, who gave generously of her time and expertise.

3 Tomas Venclova, "Ethnic Identity and the Nationality Issue in Contemporary Soviet Literature," Studies in Comparative Communism 21 (1988): 327. Also discussed in John Hiden and Patrick Salmon, The Baltic Nations and Europe: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in the Twentieth Century (London: Longman Group Limited, 1991,1994).

4 Most often Jakštas's work is mentioned with a photograph or two and a few lines identifying the maker. I am currently collaborating with historian Valdas Striužas, ethnographer Alė Počiulpaitė and the artist himself on a bilingual monograph.

5 Good" synopses of the role the Hill of Crosses has played in Lithuanian culture may be found in the following publications: Ričardas Dailidė, Kryžių kalnas [The Hill of Crosses] (Vilnius: Special Issue of Veidas, 1993); Hubertas Smilgys, Kryžių kalnas [Hill of Crosses] (Šiauliai: Momentas, 1991). The sociology of Christian pilgrimage is discussed by Victor Turner in his Dramas, Fields and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1974) and in a work co-authored with his wife Edith Turner, Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture (New York: Columbia university Press, 1978). Acknowledging the importance of the Hill of Crosses to Lithuanian culture, the Vatican chose it as the site for the open air Mass celebrated by Pope John Paul II during his visit in September 1993. Following his trip, the Pope sent a gift of a crucifix carved by sculptor E. Manfrini, which has been placed in the open area in front of the main path across the hill.

6 Victor Turner, Dramas, Fields,..: 212.

7 Details of this event may be found in Valdas Striužas, "Didysis kryžius," in Dienovidis (March 11,1995): 11. Several attempts had been made by the Soviets to raze the Hill of Crosses by bulldozing its monuments. Following each demolition, new crosses immediately appeared.

8 "The Catholic-Protestant struggle, which was at its height from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-seventeenth centuries, is

symbolized in the famous story of Our Lady of Šiluva, a small town in Samogitia. In 1457 a local nobleman, Petras Gedgaudas, built a Catholic church there dedicated to Mary... During the Reformation, the Calvinist Sofia Wnuczko... acquired the town and surrounding estate, confiscated the Catholic holdings, and established a school for Protestant ministers. Around 1606 the local Catholics... sued for the return of their properties. Tradition holds that in 1608 a weeping apparition of Our Lady appeared before a Calvinist catechist and some shepherds on the spot where Catholics had once worshipped. The Šiluva parish chronicle indicated that soon afterward there followed the remarkable discovery of parish records, including the original deed, which enabled the Catholics to win their court case in 1622. A grateful Father Kazakevičius built a chapel on the site of the apparition and restored the local Catholic church; eventually, successively larger structures were built, until in 1786 a large brick church was consecrated before a throng of thirty thousand. The cult of Our Lady of Šiluva grew continuously,... the yearly festivities attract thousands, despite Soviet attempts to curtail the celebration (during Soviet occupation]. For Lithuanians, Šiluva holds much the same religious and historic significance as, for example, Czestochowa does for the Poles." From Saulius Sužiedėlis, The Sword and the Cross. A History of the Church in Lithuania (Huntington, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitor, Inc., 1988): 66. See also "The Counter-Reformation," in Zigmantas Kiaupa, Jūratė Kiaupienė, Albinas Kuncevičius, The History of Lithuania before 1975 (Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2000): 285-288. The veneration of Our Lady of Šiluva was carried to the West by post-World War II immigrants. In the Great Upper Church of the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., the Chapel of Our Lady of Šiluva, donated by Lithuanian Catholics of America and dedicated in 1966, is located across the nave from the Polish chapel of Our Lady of Czestochowa. The border of the mosaic arch that frames the Šiluva chapel is decorated with pine cones (symbols of immortality), illustrating the meaning of the name which is related to the Lithuanian word šilas pine forest. The colorful mosaic and stained glass decorations

on the altar, chapel walls and ceiling refer to other Lithuanian Marian titles as well as a broad range of historical and cultural references, including the Hill of Crosses. Michael P. Warsaw, The National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception: America's Church (Washington, D.C, The national Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, 1990): 32-33.

9 Following a series of uprisings, the 1863 Revolt of the Lithuanian and Polish peoples against the Russians interrupted land reform and plans for the emancipation of the serfs under Czar Alexander II (1855-1881). These gestures could not alleviate the passionate nationalist movements and patriotic leaders who urged for more radical and speedy reforms. An attempt to draft some of the more outspoken members of the population into Russian military service triggered the insurrection on January 22,1863. Led by Polish and Lithuanian nobles, the poorly equipped guerrilla warfare was ineffective from the start against the Russian forces. General Michael Muraviev was appointed Governor General of Lithuania and implemented ruthless methods to suppress the revolt by 1865. He then proceeded to Russify the province by improving the lot of serfs to win their support, suppressing the Catholic Church and severely persecuting the press. However, his methods met with little success against the resistance of the people to the Russification of literature, religion and education, and in 1904 the Lithuanian press was restored by Czar Nicholas II. Algirdas M. Budreckis, An Introduction to the History of Lithuania (Private printing, 1984): 89-107; Albertas Gerutis, Lithuania 700 Years (New York: Manyland Books, 1969, rpt. 1984): 110-144; Bronius Makauskas, Lietuvos istorija (Kaunas: Šviesa, 2000): 199-243, especially 218-230. A number of memorials were erected on the Hill of Crosses in honor of those lost or exiled during the uprisings against the Czarist Russian occupation from 1795- to 1915.

10 For a discussion of the transition from religious to secular figures in Lithuanian folk sculpture, see essays by Alė Počiulpaitė, Milda Richardson and Rūta Saliklis in the exhibition catalog Sacred Wood: The Contemporary Lithuanian Woodcarving Revival, Rūta T. Saliklis, ed. (Madison, Wisconsin: Elvehjem

Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, May 30-July 12,1998).

11 The discussion of exorcism is based on William Ferns, "Folk Art and the American South," in Alice Rae Yelen, Passionate Visions of the American South. Self-Taught Artists from 1940 to the Present (New Orleans Museum of Art, distributed by the University Press of Mississippi, 1993): 14. This exhibition catalog also includes excellent essays by Alice Rae Yelen on "Religions and Visionary Imagery", pp. 135-143, and "Patriotism", pp. 233-236, in which she discusses the presence of national and religious symbols in the work of self-taught artists and their relationship to the common culture in which they thrive. In "Self-Taught Artists: Who They Are", Yelen describes the innate artistic impulses and internal ideation of artists who lack conventional training: 17-20.

12 For the role the Folk Art Society played in the power struggle for cultural and national identity, see Milda B. Richardson, 'The Heritage of Community Art in Lithuania," Advances in Program Evaluation, Vol. 4 (Stamford, Connecticut and London, England: JAI Press, Inc., 1998): 55-71. The formation and growth of the society are described in Feliksas Marcinkus, Liaudies meno draugija (Vilnius: Lithuanian Ministry of Culture, 1986).

13 Juozas Kudirka, Šalčininkėlių smulkiosios architektūros ansamblis (Vilnius: Mokslas, 1989). This photograph album on the project clearly shows the stark contrast between the more original contribution by Jakštas and the shrines of the other artists who closely follow the tradition, except for the secularization of the figures.

14 For typical examples, see figures 162, 167 or 181 in Marija Matušakaitė, Senoji medžio skulptūra ir dekoratyvinė drožyba Lietuvoje [Ancient Sculpture and Decorative Carving in Lithuania] (Vilnius: Baltos lankos, 1998).

15 The rūta or rue, is the national flower of Lithuania.

16 Maria Leach, ed.. Standard Dictionary of Folklore Mythology and Legend (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1972): 633.

17 Feliksas Marcinkas, Liaudies meno draugija (Vilnius: Lithuanian Ministry of Culture, 1986), passim; Milda Richardson, "The Heritage of Community Art in Lithuania,"

Advances in Program Evaluation, Vol. 4 (Stamford, Connecticut and London, England: JAI Press, Inc., 1998): 55-71 and "Lithuanian Wayside Shrines," Sacred Wood: The Contemporary Lithuanian Woodcarving Revival, Rūta T. Saliklis, ed. (Madison, Wisconsin: Elvehjem Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, May 30-July 12, 1998): 23-30; Vytenis Rimkus, Liaudies meno meistrų seminarai [The Seminars of Folk Art Masters]. Kaunas, Lithuania: Šviesa, 1984 and Lietuvių liaudies skulptūra: raiška ir funkcionavimas [Lithuanian Folk Sculpture: Expressiveness and Function], unpublished Ph.D. dissertation (Šiauliai Pedagogical Institute, 1994).

18 Beginning with May 14,1972, the day on which a young man named Romas Kalanta (1953-72) immolated himself in a Kaunas park to protest the Soviet occupation, numerous non-violent popular actions were enacted throughout Lithuania in its steady revolution against Soviet totalitarianism. It was a quiet revolution played out in subtle ways. It was, according to Zbigniew Brzezinski in 1989, a defeat by "force of ideas and political resistance." Quoted by Adam Roberts in Civil Resistance in the East European and Soviet Revolutions (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Albert Einstein Institution, 1991), Monograph Series Number 4:2. The moral dimension of life, which had been neglected by the Soviet regime, slowly became visible in many artistic expressions in this period of civil resistance. Folk artists like Jakštas in a low-keyed manner, but in a forceful style, expressed the ideas that the general populace related to. Many details of resistance efforts, including partisan activities, may be found in recent publications, such as Izidorius Ignatavičius, Lietuvos naikinimas ir tautos kova (1994-1998) (Vilnius: Vaga, 1999).

19 Charles A. Jencks, The Language of Post-Modem Architecture (NY: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1977): 117.

20 Jonas Balys, "Miškas ir medžiai" [The Forest and Trees], Lietuvių liaudies pasaulėjauta [World Conception in Lithuanian Folklore] (Chicago: Lietuvių tautinis akademinis sambūris, 1966): 62-70. See also "Medžio sakralumas" [Sacredness of Trees] Irena Čepienė, Etninė kultūra ir ekologija [Ethnic Culture and Ecology], (Kaunas: Šviesa, 1999): 47-79.

21 For example, Laima Sruoginytė (Sruoginis), translator, "Lithuanians by the Laptev Sea: The Siberian Memoirs of Dalia Grinkevičiūtė," Lituanus, Vol. 36, No. 4(1990): 37-67. Excerpt from memoirs by the same title (Vilnius, Lithuania: Pergalė, 1988).

22 Jakštas and many other courageous artists and writers, who dared to speak out through their mediums, represent what Prof. Thiemann of the Harvard Divinity School calls "connected critics." "Connected criticism of the public intellectual oscillates between the poles of critique and connection, solitude and solidarity, alienation and authority. Connected critics are those who are fully engaged in the very enterprise they criticize, yet are alienated by the deceits and shortcomings of their own community. Because they care so deeply about the values inherent in their common enterprise, they vividly experience the evils of their society, even as they call their community back to its better nature. Connected critics recognize that fallibility that clings to the life of every political or social organization, and they seek to identify both the virtuous and vicious dimensions of the common life in which they participate. Connected critics exemplify both the commitment characteristic of the loyal participant and the critique characteristic of the disillusioned dissenter. This dialectic between commitment and critique is the identifying feature that distinguishes acts of dissent that display genuine moral integrity from those that represent mere expediency of self-interest." Ronald F. Thiemann, "Prisoners of Conscience," Religion and Values in Public Life, Vol. 8, No. 3 (Fall 2000): 60; supplement to the Harvard Divinity School Bulletin.

23 The Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania was an underground journal which began in 1972 and for 17 years, until 1989, documented the Lithuanian Catholic struggle to survive under an atheistic and totalitarian regime. For the first eleven years, its editor was Archbishop Sigitas Tamkevičius, S.J., until his arrest for anti-Soviet propaganda. The journal circulated through participants who typed copies for private distribution along with other samizdat (self-published materials). It was smuggled out of Lithuania in parts, translated and disseminated in the United States under the auspices of Lithuanian

Catholic Religious Aid in New York. A particularly moving memoir by Nijolė Sadūnaitė, one of the leaders of this underground movement, is A Radiance in the Gulag (Manassas, Virginia: Trinity Communications, 1987). For an excellent discussion of the Chronicle's activities, see chapter 9 of The Sword and the Cross. A History of the Church in Lithuania by Saulius Sužiedėlis (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, Inc.): 207-234. Anatol Lieven discusses the participation of the Catholic activists in the rise of the national movements 1987-90 in The Baltic Revolution (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993): 219-227. Based on careful archival research, Arūnas Streikus offers more details in his chapter entitled "The Resistance of the Church to the Soviet Regime from 1944 to 1967," The Anti-Soviet Resistance in the Baltic States (Vilnius: Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, 1999): 84-112. The classic study on this subject is by Prof. V. Stanley Vardys, The Catholic Church. Dissent and Nationality in Soviet Lithuania (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978).

24 In Jakštas's work, images of fire are related to the pagan worship of the fire spirit invoked as Sacred Gabija or Gabieta (from gobti, gaubti, to pile or put together) for protection of home and homestead. As an agent of destruction and regeneration, in the Christian tradition this is carried on with the fire of Easter. Jonas Balys, op. cit., "Ugnis" [Fire]: 23-30. The use of fire in ethnographic reenactments of folk customs, especially Joninės (St. John's Eve), when the house fire is extinguished and a new one is brought from the festival pyre, may be seen in the 1999 video Kalendorinės šventės [Calendar Holidays] produced by Arvydas Barysas.

25 Maria Leach, Ibid.: 906.

Photo Credits: Figures 1-6 and 8, courtesy of Valdas Striužas. Figure 7, courtesy of Prof. Vacys Milius.