Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

Copyright © 2001 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 47, No. 3 - Fall 2001

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 2001 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

RECLAIMING SHAKESPEARE: EIMUNTAS NEKROŠIUS'S LITHUANIAN OTHELLO

PATRICK CHURA

St. Louis University

More than sixteen years have passed since Arthur Miller's description of Lithuanian theater director Eimuntas Nekrošius as "some kind of genius."1 Commenting on a performance of Nekrošius's Pirosmani Pirosmani that the American playwright had witnessed during a November 1985 visit to Soviet Vilnius, Miller called the play, "something extraordinary... an unforgettable evening...one of the best things I've seen in my life." Profoundly impressed with the Lithuanian director, Miller lamented not only that Pirosmani Pirosmani could not be brought to New York, where he believed it would be "sensational," but also that Nekrošius directed his plays "in a country with a small language" and that his work would therefore have great difficulty finding an international audience. "If Nekrošius had been born in England or France," Miller concluded, "he'd be a world figure probably."

In those days, Miller could not have foreseen the end of the political barriers that separated Lithuanian talent from the West, but it now seems safe to say that the cultural and language barriers he referred to are being overcome. In the past decade, the international stature of Nekrošius has grown steadily, and his current creative phase has solidified his reputation as one of the premier directors in Europe. Nekrošius has recently completed a remarkably successful series of Shakespearean tragedies which began with Hamlet in 1997, continued with Macbeth in 1999, and culminated in the Vilnius premiere of Othello in November of 2000. On May 26 of this year, Nekrošius's fascinating interpretation of Shakespeare's tragedy of the Moor of Venice received the three highest awards at the Kontakt 2001 international theater festival in Torun, Poland. The Lithuanian Othello won the award for Best Production, Nekrošius received the Best Director prize, and veteran Lithuanian actor Vladas Bagdonas was recognized as Best Actor for the role of Othello.

On June 10, 2001, two weeks after its triumph in Torun, Nekrošius's Othello returned to Lithuania for a single performance before a sold-out Lithuanian National Theater in Vilnius. In this production, the foundational principles of Nekrošius's successhis abilities to compellingly blend an eclectic range of "multi-genric" effects and symbolically suggest relationships between ethnic Lithuanian and world culture while maintaining vital contact with the Shakespearean dramatic textwere clearly apparent.

"Genric Eclecticism"

Explaining his art, Nekrošius has said that a theater director "is required to know how to read the production vertically, like a musical arrangement."2 A production, Nekrošius believes, must not only "speak," but it must do so on several levels, using multiple systems of meaning, in concert, to achieve a cumulative, unified effect. In this play, for example, a powerful musical score develops concurrently with an array of sound effects, extending the range of non-verbal auditory communication from director to audience. Italian critic Valentina Valentini, author of a book-length treatment of Nekrošius's work, has described this characteristic use of sound: "In Nekrošius's theater, unspoken means of expression ... carry out a narrative function in which voices (whispers, murmurs) are interwoven with opera arias, familiar excerpts from classical works, and specific sounds from the natural world, unifying the action and lending a fluidity to the performance, coloring its moods in grotesque and lyric tones."3 In Othello, sounds of rain, thunder, fire wind, seagulls, opening and closing doors, flowing water, piano, trumpet and harmonica played by the actors, and a recorded symphonic scoreall are used with varying intensity to mark time shifts in the drama, signal psychological changes, and support meaning.

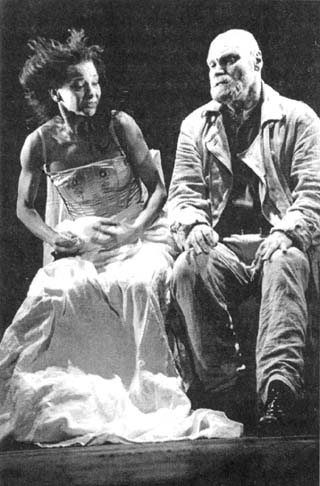

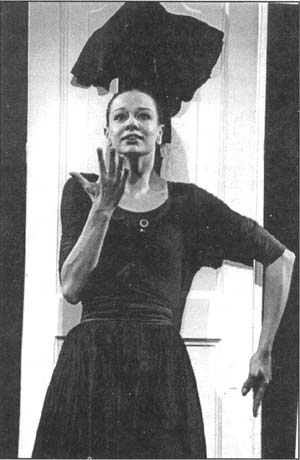

Actor movements and gestures are similarly amplified, transformed into powerfully suggestive postmodern dance. Nekrošius's choice of 24-year-old Lithuanian ballet star Eglė Špokaitė for the role of Desdemona both underscores an obvious generational contrast between the youthful Desdemona and the middle-aged Othello and allows Desdemona to express her most intense emotions through entrancing dance interludes. Her graceful movements and lithe figure are a foil to Bagdonas's military bearing of compact physical strength, and this theme is used productively throughout the play. The strong sexual nature of the love between Bagdonas's Othello and Špokaitė's Desdemona is suggested through a repeated, erotically charged duet incorporating themes of violence and tenderness, dominance and submission. As forces beyond her control or understanding alienate her from Othello, Desdemona uses dance to both reassert her power over Othello and to comfort her husband, to movingly, if temporarily, restore Othello's wavering faith in her.

Eglė Špokaitė as Desdemona. Vladas Bagdonas as Othello. (Dmitri Matveyev photo)

In this production, visual symbols proliferate. Many of the metaphors, such as Othello's sword, the contrast between light and dark, impenetrable doors, the four elements, and clearly opposed colors, are of recognizable universal meaning. The isolation and sexual innocence of Desdemona's life before Othello, for example, is suggested by the white door she carries on her back at her first appearance on stage. The black veil or ribbon attached to the door and positioned directly over Špokaitė's head foreshadows an ill-fated marriage. Later in the play, Desdemona's naiveté is poignantly conveyed when Othello's military sword, imposing and threatening under his control, becomes in Desdemona's hands an object of childish amusement, which she handles playfully. Finally, as Othello's jealousy intensifies, Desdemona's white chair and Othello's black chair gradually separate, moved apart by Desdemona as she dances frantically, but silently, between them, illustrating the estrangement of the principal characters.

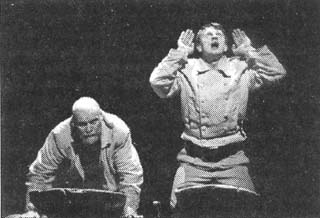

Othello (Vladas Bagdonas) and Iago (Rolandas Kazlas). (Dmitri Matveyev photo)

Critic Rasa Vasinauskaitė has called Nekrošius's Othello "a performance of visual contrastsblack and white, movement and stasis, horizontal and vertical." Though Vasinauskaitė praises the interconnectedness of the multiple forms of metaphors and their usefulness as an expression of the play's "total plan,' others have rejected Nekrošius's "genric eclecticism." A minority of critics have alleged that the director's efforts to "strengthen" or "materialize" the drama are actually a form of disguise and an insubstantial substitute for dramatic effecta heavy-handed attempt to indicate meaning that is not actually presented on stage. This criticism is certainly defensible, stemming probably from the perception that Nekrošius's stage is excessively "busy." Throughout Othello, there is seemingly always more than one active locus to the drama. Admittedly, not all of the numerous symbols and actions in Othello may be consciously registered by the audiencetheir effect is both liminal and subliminal. But as these examples illustrate, there is a textually justified consistency governing their presentation.

A "Culture-Specific" Othello

Though Nekrošius rarely discusses the social context of his art, he has repeatedly asserted the need for modern Lithuanians to maintain a strong sense of national culture.4 In Othello, objects of ethnic Lithuanian cultural significance are combined with another element of the director's customary dramatic vocabularythe four basic elements of earth, air, fire and water. Lithuanian geldostraditional wooden washing troughs from rural Lithuaniaare the most versatile and ubiquitous onstage props, holding fire for warmth, water for "washing, and the earth in which Desdemona's handkerchief is found. Collections of geldos are visually apparent in each of the play's three acts. When Othello travels from Venice to Cyprus, he takes these objects with him, dragging a fleet of themlike a burdenacross the stage. Later, the relationship between Othello and Iago is indicated by the varying distances between the two characters' fire-filled geldos. Finally, a large gelda serves as a floating funeral pyre for Othello's dead body.

Both inwardly and outwardly, the production has a noticeably Lithuanian aspect. After murdering Desdemona, Othello's overarching grief and regret compel him to painstakingly adorn her lifeless figure with planted flowers in vases, then to water them, transforming the scene of her death into a carefully tended Lithuanian gravesite. Throughout the production, the male actorsfollowing a cue from the profuse maritime imagery of Shakespeare's text wear naval-style clothing, but the fabric is of Lithuanian folk originwhite linen. The women are in simple, classic dress that would not seem out of place at a Baltic song festival. In one scene, Othello resembles an artisan, laborer or farmer, carrying in place of his sword a large carving chisel. In this production, Othello's skin is not blackened; his insecurity is not, as in many productions, the result of his marginalized social status as a Moor in Venice. As Vasinauskaitė has aptly observed, "Othello is a soldier rather than a Moor." Othello and Desdemona are from different worlds of age and experience, but they seem to share a common Lithuanian cultural vocabulary.

"Contemporary Classicism"

Where Nekrošius has been most successful, his work has been described as "contemporary classicism."5 Whether or not this Othello is sufficiently "classical" or accurately Shakespearean has been a source of disagreement. Certainly, Shakespeare's dramatic text is only one of many tools used by Nekrošius to communicate meaning, and this fact is underscored by the long moments of silence that punctuate Othello. The play develops slowly and, of the more than four hours' duration of the production, less than half is spent on the recitation of the verbal text. There are numerous "plays within the play," some occurring as active ensemble movements set to music or sounds, others in prolonged, silent pantomime. Valentini has attempted to describe Nekrošius's rationale: "The silence seems to the audience an appropriate method of expression, uniting the felt, the sensed, the understood, the abstract and the allegorical, circumscribing and ordering the 'contemporary classicism' of Nekrošius's theatre."

Though there are, as in most modern productions of Shakespeare, omissions in the presentation of the written text, there are also several instances of notably effective textual interpretation, especially by Bagdonas's Othello. Lithuanian critic Daiva Stanevičiūtė has noted that Othello "is strongest when he is in the world of his monologues," and this is apparent from the opening moments of the play. Bagdonas's monologue explaining Othello's effect on Desdemona"She loved me for the dangers I had passed,/And I loved her that she did pity them" (I, iii)is forcefully, stridently delivered, on the edge of the proscenium and center stage, in the midst of the audience. As Vlada Kalpokaitė, critic for the Vilnius weekly Literatūra ir menas (Literature and Art) has observed, Bagdonas in this speech "transforms the proud, rude and inarticulate general into a heroic statue come to life, a true literary hero of humanity like Gulliver, Ilya Muromeca or some other colossus, whose steps shake the earth, whose head is in the clouds." In a later scene that unites several of the director's constructive techniques, Othello's final monologue describing himself as "one that loved not wisely but too well... perplexed in the extreme... whose hand... threw away a pearl richer than all his tribe" (V,ii) is movingly recited as the Moor measures and prepares his coffin-gelda.

Margarita Žiemelytė's Emilia also has moments of strong textual treatment, especially with Desdemona in the play's final act, as she resentfully explains her vexation with male-imposed standards of female behavior. Throughout the play, the speech and gestures used by Emilia with Iago, by Emilia with Desdemona and by Cassio with Bianca offer a contrast to the dialogue between Othello and Desdemona. Compared to the play's central couple, all others are juvenile pairings, whose love relationships are on a much diminished scale. Before giving Desdemona's handkerchief to Iago, for example, Emilia coquettishly forces Iago to twice kiss her foot.

Desdemona's youth, innocence and inexperience are clearly expressed in Eglė Špokaitė's spoken language and in her frequent playful behavior with Emilia, who appears to share a schoolgirlish friendship with Desdemona. Desdemona's lighter moods, however, are emphatically offset by the strong pathos she conveys when paired with Othello. When Othello is on stage, Špokaitė's expressions follow his every movement with fascination, seemingly worshipping him up until the moment she is murdered by him. Tall, beautiful and elegant, Špokaitė uses ballet as an extremely moving supplemental expression of Desdemona's inner nature.

Desdemona. (Dmitri Matveyev photo)

Rolandas Kazlas's Iago is at times quite clearly an adolescenthis relationship to Othello is that of a pupil to his master. Even as he proclaims his hatred for the Moor, he is in awe of Othello, and his fear of the Moor is evident. In the presence of Othello, Iago hesitates unwillingly and in spite of himself, always allowing the general to physically precede him across the stage. As he plots against the Moor, he is frequently interrupted and sent scurrying into hiding by the appearance of the figure of Othello in the backstage darkness.

To several critics, this unusual Iago has presented a difficult and enigmatic problem. Stanevičiūtė has straightforwardly noted that "this drama cannot be accounted for by Iago's intrigues." In Kauno diena (Kaunas Day), Vaidas Jauniškis ended his review of the play's premiere with a question that reveals a fundamental ambiguity in Kazlas's portrayal: "Is Iago, seated beside Othello's coffin with a raised flaming finger, a grieving mourner, or a demon, testifying to the existence of pure evil?" Konstantin Stanislavsky, one of Nekrošius's acknowledged mentors, has written of the "double nature' of Iago,6 the division between Iago's weaker public self and his stronger private persona, which is aggressively vindictive toward Othello. Here, however, Iago advances the plot against Othello at those moments when he is ruled by weakness, not strength. Certainly, one cannot imagine Kazlas's somewhat cowardly and fragile Iago glorying either in his triumph over Othello or in the wider effect of his intrigues, the compulsion for which is never made fully clear by either Shakespeare or Nekrošius. Nekrošius's Iago seems to destroy Othello almost unwillingly, more a servant of evil than its author.

Noting the frequent references to and uses of water in the play, Jauniškis explains the possibility of both "elemental" and human sources for the tragedy: "Perhaps the water does not represent [Iago's] deceit, but is simply a natural element, upon which we are all sailors, in geldos split apart by passions?" The play's storms, rain and flowing water coincide with Othello's growing anger, and the audience strongly senses that it is some inevitable factor in the environment in which Othello and Desdemona exist, not Iago's evil, which is the primary stimulus to the tragedy.

Inarguably, Nekrošius's focus on the love relationship between Desdemona and Othello develops at some expense to an emphasis on the Othello-Iago plot. Nevertheless, Stanevičiutė's assertion that "... the conception of Iago's relationship with Othello is the weakest part of the whole performance" is not necessarily indicative of an artistic shortcoming in the production. Though Nekrošius is well-known for his stance that "for a person of talent, tradition does not exist," this non-traditional Iago represents much more than an uninformed iconoclasm. A comparison of this treatment of Iago with the dominant portrayals of the Soviet era, during which Nekrošius learned his craft, suggests that Iago's changed role in the drama may have less to do with Nekrošius's rejection of the past than with a calculated desire to reconsider and transform it.

Removing "layers of ideological dust"

It was no accident that Othello, not Hamlet or King Lear or Macbeth, was by far the most often staged play on the highly politically pre-occupied Soviet stage. As major Soviet Shakespeare criticism suggests,7 Othello had often been used by Soviet political authority as a convenient vehicle for exploring and depicting what Smirnov refers to as "the epoch of primary accumulation" (64) or what Morozov terms "the rise of the bourgeoisie" (44). That there were only 14 productions of Hamlet and 78 productions of Othello in the USSR between 1945 and 1957 testifies not simply to the ideological intractability in a Soviet context of the former, but to the amenability of the latter.8 According to Soviet theory, the play's initial setting in cosmopolitan, commercial Venice came to represent the bourgeois capitalist state, and Othello the Moor stood for the humanism through which Shakespeare himself expressed opposition to the bourgeois world view. Iago was the clear focus of the play's presentation of a concentrated evil that was under the terms of Soviet socialist realism always presented in a highly specific form. According to Soviet-era Lithuanian critic E. Kuosaitė in 1964, Iago embodied the "autonomous and intolerant forces" of historical regressivism and represented the "injustice" of the "old world" that wished to "prevent humanity from establishing a brighter future."9 Dovydas Judelevičius, a Lithuanian theater scholar whose 1964 Gyvasis Šekspyras (The Living Shakespeare) is still the major critical evaluation of Shakespeare on the Lithuanian stage, provides a telling Kruschev-era synopsis of the play's meaning under Soviet hegemony:

Iago is cynical and selfish, and his individualistic mindset accurately characterizes the cruel ethic of the entire historical epoch. ... Though Iago is a scoundrel in many small ways, he is a more dangerous "Machiavellian" in his entire life philosophy, demonstrating a consistent, sober program of cynicism. Bourgeois critics like to say that Iago seems to personify man's inherent evil. But Shakespeare actually created him more suitable to another purposethat in his actions, as in a tiny droplet or in a sharp focus, would be concentrated the darkest characteristics of the historical epoch that both opposed Othello's humanism and cleared the way for the ethic of the bourgeoisie (Judelevičius 19-20).

Clearly, it is a long way from this formidable Iago to Nekrošius's Iago, referred to by Jauniškis as "a schoolboy in a T-shirt." But if Iago's evil had traditionally been the center of the play's political meaning, Nekrošius's deemphasis of the role is neither inexplicable nor surprising. In this first post-Soviet production of Othello on the Lithuanian stage, in fact, several of the properties the play had acquired under Soviet ownership are extensively redefined. Forces of passion, not politics, dominate this play, and so, as Vasinauskaitė has observed, it is in one sense "Desdemona's youthful charm, childish naiveté and purity, rather than Iago's evil, that causes Othello's envy and the tragic end." Shifting the focus from Iagobesides accentuating Špokaitė's engaging Desdemonaalso helps Nekrošius to foreground the figure of Othelloa valiant relic from the distant cultural and historical past, a figure whose cross-generational relationship with Desdemona struggles painfully against the leveling, elemental and universal forces of time and change within a culture-specific Lithuanian setting.

Othello's status as the obvious elder of Nekrošius's play stresses his role as a physical link to a remote, romantic and tragic past. Surrounded by young actors, Bagdonas is a patriarchal figure. As Shakespeare's text clearly indicates, and as Bagdonas's Othello powerfully asserts, Othello woos Desdemona with the story of his past, with the "passing strange" and "wondrous pitiful" life history that he relates as Desdemona listens "with a greedy ear." She adores Othello for the "dangers" he has "passed," and the Moor loves her "that she did pity them." The large age-difference between Othello and every other character in the play lends credence to the authority and effect of his tale.

Seemingly recognizing this reflection of cultural antiquity in Othello, Vlada Kalpokaitė has described Bagdonas's Moor as "an ancient... a hero from a past age, when everything was said and done in capital letters, when there existed a concept of 'heroism' and 'duty'... when all was serious and painful... who painfully reminds the sporting boys and girlsIago, Desdemona and the entire worldthat there were indeed once heroes." As the play develops, the terms of this cross-generational liaison between the Moor and Desdemona strongly suggests a commensurate cross-generational relationship between an obviously pre-Soviet Lithuanian past and its younger counterpart, manifested physically on stage in Špokaitė and Bagdonas. In this way, the working out of the tragedy manages to speak more directly about the relationship of the Lithuanian past to the Lithuanian present than it does about the vague form of evil embodied in Iago.

In Soviet days, it had been fashionable to assert that Soviet ideology had rescued Shakespeare's humanism from the ash heap of history, from what Smirnov referred to as the "gigantic moral cataclysm" of the "downfall" of the bourgeoisie. In 1964, Judelevičius, had described this politically oriented position:

Soviet directors have opened up a new Shakespeare. From the heights of socialist realism the contemporary relevance of Shakespeare's philosophical wisdom has been proclaimed. Shakespeare's philosophy has been rid of the thick layers of ideological dust from the nineteenth century (43-44).

The essence of Nekrošius's beautiful Othello certainly is not (as had often been the case with the play in the Soviet era) a grossly conveyed political moral or ideological agenda. The contrasts between this production and its Soviet predecessors, however, are striking, and they indicate that Nekrošius's own creative processremoving "layers of ideological dust" from the play's antecedents, thereby proclaiming a new "contemporary relevance" for the dramanecessarily conveys and contains both cultural and political meaning. As critics have noted, a formal iconoclasm or "contemporary classicism" has always been a distinguishing feature of Nekrošius's work, but it would be naive to claim that this artistic stance could ever be historically uninvolved or politically neutral, if not in content, at least in its effect. Considered in its historical context, Nekrošius's Othello not only confirms the director's brilliance and furthers his international standing, but also clearly reflects the apparent reordering of the terms and power relations governing Shakespeare reception in Lithuania.

Nekrošius's Othello will be performed in Parma, Italy on October 6 and 7, and St. Petersburg, Russia on October 14. It is scheduled to return to Lithuania for performances in November and December, of this year.

Emilia, Desdemona, and Bianca. In the foreground, a collection of geldos. (Dmitri Matveyev photo)

WORKS CITED

"Arthur Miller in Vilnius: An Interview." Baltic Forum 3.1 (Spring

1986).

Jauniškis, Vladas. '"Otelas tarp Vilniaus ir Venecijos." Kauno diena 9

December 2000.

Judelevičius, Dovydas. Gyvasis Šekspyras (The Living Shakespeare). Vilnius:

Vaga, 1964.

Kalpokaitė, Vlada. "Tarp verkiančių durų." Literatūra ir menas

(Literature and Art) 8 December 2000:1,8.

Kuosaitė, E. "Šekspyras ir dabartis (Shakespeare and the Present)" Švyturys (Lighthouse) (March 1964) 20-21.

Stanislavsky, Konstantin. Stanislavsky Produces Othello, tr. Helen Nowak. London: Geoffrey Bles, 1948.

"Valentina Valentini kalbasi su Eimuntu Nekrošiumi." (Valentina Valentini Talks with Eimuntas Nekrošius). Teatras (Theater in

Lithuania). 2.8 (2000): 50-51.

Valentini, Valentina. Eimuntas Nekrošius, tr. Inga Tuliševskaitė (translated into Lithuanian from the Italian) in Teatras (Theater in Lithuania). 2.8

(2000): 52-55.

Vasinauskaitė, Rasa. "Dvi gulinčios figūros" 7 Meno dienos 1

December 2000, 1.4.

1

See "Arthur Miller in Vilnius: An Interview." Baltic Forum 3.1

(Spring 1986).

2

See "Valentina Valentini kalbasi su Eimuntu Nekrošiumi." (Valentina Valentini Talks with

Eimuntas* Nekrošius). Teatras (Theater in Lithuania). 2.8 (2000): 50-51.

3 See Inga Tuliševskaitė's excerpt (translated into Lithuanian from the

Italian) from Eimuntas Nekrošius, Valentini's 1999 book-length text. Teatras (Theater in Lithuania). 2.8

(2000): 52-55.

4

In the aforementioned interview with Valentini, for example, Nekrošius asserts, "I don't believe in multicultural orientation. People must develop roots in their own culture and become deeply rather than superficially immersed in it. I would put it this way: it is better to know less but know it well, than to understand superficially. I am against fragmentary culture, against the 'merry-go-round of images'."

5

Valentini has foregrounded this term, but several other critics, Lithuanian and foreign, have used it as well.

6

See Stanislavsky Produces Othello, tr. Helen Nowak. London: Geoffrey

Bles, 1948.

7

Helpful works in this area include those, of Nikolai Gorchakov, Dovydas Judelevičius, P.A. Markov, Eleanor Rowe, R.

Samarin, M. Morozov, and A.A. Smirnov. See also my article, "Hamlet and the Failure of Soviet Authority in Lithuania" in Lituanus 46.4 (December 2000): 8-46.

8 From 1945 until 1957, Othello was staged seventy-eight times in the

Soviet Union, Romeo and Julietfifty times. During the same period, King Lear was

premiered sixteen times and Hamlet fourteen" (Judelevičius 140). In Shakespeare on the Soviet Stage (1947)

Mikhail Morozov had acknowledged that "Hamlet is performed on the

Soviet stage comparatively seldom... Whereas... Othello has had over one

hundred and fifty productions"(44).

9 See Kuosaitė, E. "Šekspyras ir dabartis (Shakespeare and the

Present)" Švyturys (Lighthouse) (March 1964) 20-21.