Editor of this issue: M. Gražina Slavėnas

Copyright © 2001 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 47, No. 4 - Winter 2001

Editor of this issue: M. Gražina Slavėnas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 2001 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

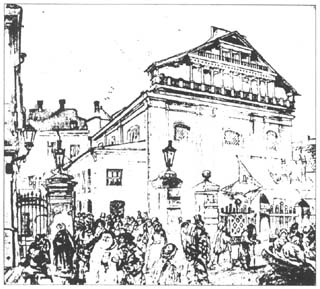

Great Synagogue of Vilnius (J. Kamarauskas, watercolor, 1899)

THE HARD LONG ROAD TOWARD THE TRUTH:

On The Sixtieth Anniversary Of The Holocaust In Lithuania

SOLOMONAS ATAMUKAS*

This is a difficult and painful theme from what seems to be a distant past. But history is such that problems do not vanish nor disappear with time, and the need to record past events becomes even more urgent as the number of participants and witnesses decreases. Sooner or later the truth has to be faced and events must take their rightful place in the historical process.

This year is the sixtieth anniversary of the Holocaust of Lithuanian Jewry, which began in Lithuania on June 22, 1941. This is also the date that marks the onset of the war between Nazi Germany and the USSR and the blitz advance of the German army into Soviet-occupied Lithuania. For the Jews of Lithuania, this date signifies the first step in the actual implementation of Hitler's ravings about racial purity and his desire to wipe out every trace of Jewish life from the face of Europe. Beginning in Lithuania, the Hitler regime began the actual implementation of the plan for mass executions of bigger and bigger groups of Jews in an organized and systematic way by special death squads composed of Germans and Lithuanians. Precise numbers will perhaps never be known, but at the end of 1941 and the beginning of 1942, out of a total of some 240,000 Lithuanian Jews, about 170,000-180,000 were killed in mass executions in various locations throughout Lithuania, most of them at the Kaunas Ninth Fort and in the forest of Paneriai (Ponary) near Vilnius. The liquidation of the Vilnius Ghetto on August 23, 1943, signaled the last phase of the destruction of Lithuanian Jewry on the very soil on which they had lived since the Middle Ages. In the words of Nobel Prize winner Eli Wiesel, "Not all Nazi victims were Jews. But all Jews were victims."

How was such horror possible? To this day, Lithuanian Jews who witnessed these gruesome events try to come to grips with the memory of their neighbors turning against them and to understand what is probably beyond understanding.

The Jewish community in Lithuania has very deep roots. Jewish history dates from the fourteenth century, when Jews were invited by Grand Duke Gediminas to settle in the lands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Lithuanian Jews continued to refer to the entire area of the former Grand Duchy as Lita and were themselves known as Litvaks. Learnedness, rational thinking and a dry sense of humor were personality traits characteristic for the Litvaks, distinguishing them from the neighboring Hassidic Jews. The dominant group was Ashkenazy which had migrated from Germany through Poland. For centuries, Vilnius (Jews call it Vilna or Wilno) was famous as the center of Jewish religious and cultural activity. It was a great center of Jewish worship and Talmudic learning and an important center of the Haskala movement. The first synagogue was built there in the sixteenth century. The legendary Great Synagogue of Vilnius, with its floor below ground level, had the dimensions of a cathedral. (See illustration on p. 4). Jews lived and worked among Lithuanians for many centuries in relative safety and escaped major dislocations or pogroms which occurred in neighboring countries. For the Jewish world, Lithuania was not a country of pogroms.

In 1918, Jewish leaders supported Lithuania's claim for independence and to Polish-occupied Vilnius. Several hundred Jews volunteered for the Lithuanian army to fight the Poles. The new republic adopted a modern democratic constitution that honored the rights of its minorities. Jews were granted full autonomy under the Constitution and were represented in the government. During the first years of the Republic, several Jewish officers served in the army and a number of senior Jewish officials in the administration, including a Minister for Jewish Affairs. Beginning with the Christian Democratic administration in 1923 and after the Smetona coup of 1926, Jews found themselves excluded from government service, and all offices were filled by ethnic Lithuanians. President Smetona, however, respected minorities and official anti-Semitism was not tolerated. The Jewish Community had its rights protected under the law and was loyal to Smetona. Abroad, Litvaks were Lithuania's best friends and advocates.

The loss of Vilnius to Poland in 1922 was a great loss for the Jewish community as well. It adjusted to the realities and moved its center to the temporary capital Kaunas. Before 1918, Lithuania was largely an agrarian society and in the early years of the republic, Lithuanians were unable to compete with Jews economically or professionally. Jews held a high proportion of urban positions and greatly outnumbered and excelled Lithuanians in business and in the educated professions. They also controlled commerce and banking. It is little appreciated that with their expertise and foreign contacts, Lithuanian Jews made significant contributions to the economic growth and prosperity of the new republic. They also greatly expanded their own educational system. There were some 300 private Jewish elementary schools, twenty high schools and a teacher's seminary, partially subsidized by the government. Lithuanian was also taught in Jewish schools. A new Yeshiva was built. Jewish hospitals also served Lithuanians. In pre-war Lithuania the Jewish Community, with about 7.6 percent of the population, became its largest, most visible and economically most successful minority. Their numbers increased significantly in 1939 after the return of Vilnius and the Vilnius region to Lithuania. In 1940, their number grew to 8-8.5 percent.

General assumptions to the contrary, the Jewish Community was not monolithic but multifaceted. In addition to the old rivalries between the Hassidic and the Orthodox, another struggle developed between Zionists and the socialist labor group, The Bund. Zionists promoted Hebrew while Bundists supported Yiddish, which was also the language most Lithuanian Jews spoke at home and especially in the small towns. There was also a small illegal Communist party.

With the rise of Nazi Germany, Lithuania, like the rest of Eastern Europe, was flooded with Nazi propaganda. Nazi theories about racial superiority and ethnic cleansing fell on fertile ground for many reasons. As in all Christian countries, there existed the usual prejudices and myths, especially in the countryside. Before 1917, the Jewish intelligentsia was steeped in Russian culture and literature. Lithuanians, having just gained their national identity, idealized their own language and culture. Patriotism was defined in national and religious terms which did not include other ethnic or religious groups. Chauvinistic young Lithuanians with their slogans of "Lithuania First" resented the use of Russian in public and were quick to ridicule Jewish accents and dress, especially in the countryside. The language question was so acute that a language requirement was instituted for students entering the university. This reduced the number of Jewish students. All in all, Lithuanian Jews made great progress in adapting to the emerging Lithuanian culture and the young generation was fluent in Lithuanian.

The major reason for the growing anti-Semitism was economic and professional competition. By the mid-thirties, fifty percent of the Lithuanian population was already in towns and aspired to jobs the economy was too weak to support. Lithuania was also hard hit by the worldwide economic crisis. Lithuania's new educated middle class inevitably came into professional conflict with its Jewish rivals. The traditional Jewish role in business and the professions became a cause for envy and resentment. The Lithuanian student corps even called for a quota system for university admissions. University presidents Stasys Šalkauskis and Mykolas Romeris denounced anti-Semitic manifestations among the student body.

An even more ardent and vocal rival was the Lithuanian business class. Although government-subsidized Lithuanian cooperatives barred Jewish expansion, the Lithuanian Businessmen's Association demanded even more government restrictions for its Jewish competition. Openly anti-Semitic was its periodical Verslas (Trade), urging outright boycotts of Jewish businesses. The extreme fascist fringe, the "Iron Wolves", resented Jewish shop signs and imitated examples in Nazi Germany of anti-Jewish rhetoric and occasional acts of vandalism against Jewish business establishments, smashing windows and smearing Yiddish signs with anti-Jewish slogans. In view of these developments, about 20,000 Jews took advantage of opportunities to emigrate and left Lithuania, albeit taking with them their capital, investments, foreign contacts and expertise. Young Jews turned to the Communist Party, which proclaimed internationalism and ethnic equality. This added to the perception of Jewish allegiance to Communism. Stasys Yla, a Catholic priest, under the pseudonym Daulius, bluntly stated that Jews "wanted to rule the world" and could achieve it best through Communism" (J. Daulius, Komunizmas Lietuvoj, Kaunas: 1937,198-206).

Most disconcerting to the leaders of the Jewish community was the spread of radical Lithuanian nationalism coupled with Nazi ideology among young Catholic intellectuals and young radical nationalists in the Tautininkai (Nationalist) party. Adapting pseudoscientific theories about racial superiority and pure nation-states, the respected young philosopher Antanas Maceina, a Christian Democrat, attracted attention with his famous article "Tauta ir valstybė" (Nation and State) presenting the case that minorities were "incompatible foreign matter" in the "body of a nation" and unable to ever become a part of it. The article ended with the words: "...making our state a Lithuanian one....is our national honor and responsibility" (Naujoji Romuva <New Romuva> 1936. 7, 167-175). The geographer Stanislovas Tarvydas reiterated the all-Lithuanian formula in his book "The new state bases its existence not on citizenship but on nationality" (Geopolitika. Kaunas: 1939. 17, 277). Vytautas Alantas, editor of the semiofficial newspaper Lietuvos aidas (Lithuania's Echo) went as far as to advocate for a separate beach for Jews ("Aktualieji paplūdimo klausimai," 26 August 1938). Together with Vincas Rastenis and Bronys Raila he suggested to take lessons from the way Hitler's racial policies were implemented in Poland. A number of well-known scholars and statesmen raised their voices against extremism. Dr. Jonas Šliūpas, a distinguished veteran of the National Liberation Movement and editor of its publication Aušra (Dawn) as well as founder/editor of the first Lithuanian American newspaper in the U.S., wrote in 1939 that anti-Semitic manifestations are usually indications of serious troubles in a country or society ("The meaning of anti-Semitism." Laisvoji mintis <Free Thought>, 15 July 1939).

On the eve of World War II, Lithuania experienced serious political setbacks. The Smetona government was forced to accept two deeply humiliating ultimatums. In 1938, Lithuania had to reinstate diplomatic relations with Poland without getting back the city of Vilnius (Wilna) and surrounding areas. In March 1939, faced with German aggression, it signed over to Nazi Germany the city and territory of Klaipėda-Memel. The war broke out in September and Germany marched into Poland while the Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland, including Vilnius and the Vilnius area. On October 10, Lithuania accepted a Soviet ultimatum allowing the Soviet Union to establish military garrisons in the country. In return, The Soviet government promised to respect Lithuanian sovereignty rights and returned Vilnius and the surrounding area, creating a general feeling of euphoria among the Lithuanians and Jews. Faced with the Nazi alternative, at that moment in history, much of the country and the government viewed the Soviet alternative as a better choice. When in June of 1940 the Soviet Union demanded total access for its troops and the formation of a new "friendly" government, the majority in the government turned against President Smetona and agreed to these demands.

It must be kept in mind that all political decisions at that time were made by Lithuanians. Later accusations that Lithuania was "sold" to the Soviet Union by the Jews had no foundation. The Jewish Community had no representation in government to influence events and no say in these deliberations. Nor did Jewish members of the Communist party, which did not have a political program on Lithuania's future status. Realistically speaking, Jews had no other alternative. Young Jewish communists and some other disaffected segments within the Jewish community cheered the arrival of Soviet tanks. For Lithuanians, this was proof that Jews were Soviet supporters. Contrary to Lithuanian belief, the Jewish Community at large supported Lithuanian independence which safeguarded its own status therein. It also supported the President's policy of neutrality.

In June 1940, the Red Army moved its forces, including the secret police units (NKVD), into Lithuania, and placed it under Moscow's control. The Soviets introduced a system of political repression which culminated in the first massive deportation of Lithuania's civilian population to Siberia beginning on June 14,1941. Lithuanian authors tended to overlook that the deportation also included Jews and that proportionately more Jews than Lithuanians were deported. Yet the Jewish Community had to shoulder the blame for the activities of the small Communist minority which became active in the Soviet system. Not the guilty individuals, but the Jewish Community at large. This terrible accusation was first formulated in Berlin by an anti-Soviet resistance group called the Lithuanian Activists' Front (LAF).

LAF was created in Berlin under the initiative of former diplomat Col. Kazys Škirpa to function as the German-based center of underground resistance groups which began to form in Lithuania against the Soviet occupation. Its members were political refugees, among them the above-mentioned Yla, Maceina and Raila. Working in close cooperation with Nazi authorities, LAF attempted to maintain contact with the underground leaders in Lithuania. The Berlin Front attempted to coordinate the planned uprising in anticipation of the impending war. An important part of LAF activities was preparation and dissemination of anti-Semitic propaganda. For this purpose, an ideological commission and a propaganda section was created, with Maceina and Raila in charge. Utilizing already existing prejudices and resentments, LAF issued leaflets and communiqués in which Lithuanian Jews were denounced as traitors and KGB agents and were made responsible for the deportations and all other political repression by the "Bolshevik-Jewish" regime. All patriotic Lithuanians were urged to take up arms and create a "new" Lithuania free from the "Jewish yoke". In its program, LAF took it upon itself to revoke all previous Jewish rights and privileges. Virulent anti-Semitism was characteristic for LAF publications (cf. Valentinas Brandiškauskas "Lietuvių ir žydų santykiai 1940-1941 metais" <Lithuanian and Jewish Relations> and "Lietuvių Aktyvistų Frontas, Laikinoji vyriausybė ir žydų klausimas" <LAF, the Provisional Government and the Jewish Question>, both reprinted in Alfonsas Eidintas, ed., Lietuvos žydų žudynių byla <The Case of the Massacre of the Lithuanian Jews>. Vilnius: 2001. 688-693; 626-652).

On June 22, Germany declared war on the Soviet Union and marched into Lithuania. At the same time, the anti-Soviet uprising began. On June 23, a LAF member proclaimed in a radio address the restoration of Lithuania's independence and the formation of a Provisional Government that put itself in charge of the country and the nation-wide anti-Soviet uprising. The German army marched into Kaunas on June 24 in parade formation. On the night of June 25, an ugly German-inspired large-scale pogrom took place in Kaunas, followed by the gruesome massacre at the Lietūkis agricultural cooperative garage. The first killings occurred in border areas even before German troops reached Kaunas (Dov Levin, "Die Beteiligung der litauishen Juden im Zwei-ten Weltkrieg" <Participation of Lithuanian Jews in World War II>. Acta Baltica. 1976: 182-183; Valentinas Brandišauskas, Siekiai atkurti Lietuvos valstybingumą, ibid.).

For most Lithuanians, the German invasion meant liberation from the hated Soviet regime and the hope of independence. For all Jews it meant Nazi persecution and Polish-style ghettoization. The only escape was to follow the retreating Red Army into the interior of the Soviet Union. Only about 8,000 to 10,000 young people without families succeeded in doing so. The community at large was not prepared for war and had no place to go anyway. Inflammatory anti-Semitic propaganda was continued in the LAF newspaper Į laisvę (To Freedom), creating anti-Semitic mass hysteria. As happened so often in Jewish history, the Jewish civilian population became a helpless target for a dangerous explosion of hate, revenge, ideology, patriotism, power, and greed.

The newly created Provisional Government was very short-lived. During the six weeks of its existence it implemented anti-Jewish legislation which hastened the destruction of Lithuanian Jewry. On June 30, the Provisional Government approved the formation of a concentration camp. All Jews in Kaunas were ordered to leave their residences and move to the new location. All had to wear yellow stars. Their property was confiscated, if not looted first. Their Lithuanian citizenship was revoked. These regulations were extended to Jews across Lithuania, isolating them from the rest of the population and leaving them outside the protection of the law.

Following German orders, the Provisional Government also authorized the formation of a so called home guard battalion (Tautinio darbo apsaugos batalionas, known as TDA), which was later expanded into auxiliary police battalions that resistance fighters were encouraged to join. Members of these battalions were identifiable by white armbands on the sleeves and were known by many names such as "nationalists," "rebels," "partisans," "police," "resistance fighters." They came under the control of German Einsatzgruppen, whose main task was to protect the German army by cleansing the area of communists and other hostile elements. In reality, this meant Jews. Two Lithuanian units were immediately assigned to their mission of rounding up, transporting, guarding, and finally shooting Jews. The first mass executions took place at the Kaunas Fort VII on July 4 and 6 (Stasys Knezys, "Kauno karo komendantūros Tautinio darbo batalionas 1941 m.", Genocidas ir rezistencija <Genocide and Resistance>, 1/7. 2000: 133). According to a top secret report of December 1, 1941 by SS Standartenführer Karl Jäger, Lithuanian battalions under the control of Special Unit 3 carried out the mass executions of July 4 and 6 ("Document No. 1" in Eidintas, 283-285). The image of white-banded militia men as murderers and tormentors is indelibly burned into Jewish memories and has become identical with the name Lithuanian. Several thousand German, Austrian and French Jews were also brought to Lithuania for mass execution (Arūnas Bubnys "Lietuvių karinės policijos struktūros ir žydų persekiojimas" in Eidintas, 694-698).

Mass executions in Kaunas were under the command of SS Standartenführer Karl Jäger. According to research by German historian Knut Stang, the most notorious death squad in the provinces was the mobile unit (Rollkommando) under Obersturmführer Joachim Hamann. It was made up of forty Germans and approximately sixty Lithuanians commanded by Bronius Norkus. The scenario of the mass executions in the provinces was simple. Hamann's group (two to ten Germans) would arrive in cars and a somewhat larger number of Lithuanians by truck just prior to the shooting, which they would then direct. Local authorities were responsible for local preparations such as digging the pits, herding the victims, and initiating and/or participating in the shooting. By Hamann's own calculations, during the short period July to October 1941, his Rollkommando killed some 60,000-70,000 Jewsmen, women and childrenin 55 Lithuanian settlements (Kurt Stang. Kollaboration und Massenmord. Die litauische Hilfspolizei, das Rollkomando Hamann und die Ermordung der litauichen Juden. Frankfurt/Main: 1996. 158 165; see also the above mentioned report by Jäger (Eidintas, op. cit. 283-291). Stang also provides useful new information about the relationship of the Hamann unit with the Lithuanian units. According to Stang's records, several hundred Lithuanian men defected after the first executions but a certain number returned. This does not qualify as mass desertion. Lithuanian historians have pointed out numerous errors of fact or interpretation in Stang's research, but are not questioning his main premise (Sužiedėlis, "Kas išžudė Lietuvos žydus?" <Who killed Lithuania's Jews?>. Akiračiai 1998/4). Additional research in Lithuanian has been made available by Rimantas Zizas ("Lietuvos kariai savisaugos batalionuose 1941-1944 m.," Lietuvos Archyvai. Vol. 11. Vilnius: 1998. 38-70. Also see "Lietuvos viešoji policija ir policijos batalionai,1941-1944", Genocidas ir rezistencija. 1/13 1998. 81-104. In view of all this it is surprising to read an article in the 1994, 5-6 issue of the magazine Karys (Soldier), about the activities of twenty-five battalions without a single mention of the executions.

A no less lethal all-Lithuanian special unit operated in Vilnius. This so-called Vilnius Special Unit (Ypatingas būrys) consisted of 100-120 Lithuanians who served by rotation. According to research by Arūnas Bubnys, this unit killed some 40,000 Jews by November 1941. It was mainly responsible for the mass killings in the Paneriai (Ponary) woods and other towns in the Vilnius district. Aleksandras Lileikis was in charge of the Security Police in Vilnius and authorized orders to deliver Jews to German authorities (Arūnas Bubnys, "Vokiečių Saugumo policijos ir SD ypatingasis būrys Vilniuje 1941-1944", Atminties dienos <The Days of Memory>, Emanuelis Zingeris, ed., International Conference in Commemoration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Liquidation of the Vilnius Ghetto, October 11-16,1993. Vilnius: 1996,181-189).

Lileikis was accused of war crimes but because of endless postponements of his trial, he died before his case was completed. Innocence as well as guilt must be determined by a court of law, not by friends, enemies, or public opinion. Alfonsas Eidintas, drawing on his experience as Lithuania's ambassador to the U.S., makes a point that the Lileikis case caused hundreds of letters and articles in Europe and the U.S. about Lithuania's unwillingness to bring accused war criminals to justice. Lithuania also lost significant support in the U.S. Congress and the State Department (Eidintas, 222-235).

During a panel discussion on Lithuanian TV, on the eve of September 23, 1999, Rimvydas Valatka, assistant editor of the daily Lietuvos Rytas, said the following: "Judges, courts, and politicians wait for these people to die. And yet, this is the worst possible choice, for death can neither convict nor exonerate... In many ways Lithuania is becoming more and more provincial... There are not enough people willing and able to face the truth with an open mind" ("Tiesos apie save nesibijojimas" <Not to be afraid of the Truth>. Lietuvos Jeruzalė 1999: 7-8).

On October 15, 1941, the head of Einsatzgruppe "A" operating in the Baltic countries, SS Brigadenführer and Police General Walter Stahlecker, wrote his much-cited report (used in the Nuremberg Trials) about the successful liquidation of Communists and Jews in the Baltic states with good participation by local nationalist forces. This fact was reiterated by Karl Jäger in secret report of December 11, 1941. By January 20, 1942, when the concept of the "Final Solution" was being formulated at the Wannsee Conference in Berlin, the "Final Solution" in Lithuania and the other Baltic countries was essentially completed. Before the establishment of the gas chambers in Auschwitz and Treblinka, approximately 94 percent of the Litvak community was shot to death. It is in the light of this immense tragedy that we read Dr. Elchanan Elkes' "Last Will and Testament" to his children written in 1943 and forever cursing Lithuanian murderers. The poet Sigitas Geda, translator of the "Song of Songs", republished Elkes's testament in Šiaurės Atėnai (Athens of the North) with the following preface: "We have not paid our debt. It does not matter that we didn't know we had a debt. It does not matter that we, or our parents, or our grandparents, did not kill anyone. We belong to a nation that raised murderers. I am afraid that any decent person reading this text will stop smiling. I feel it in myself and through myself" (13 May 1995).

It is now generally agreed that the mass executions were organized and supervised by the Nazi leadership, but placing the blame on Germans cannot exonerate participating Lithuanians. It appears that the hard-core shooting was accomplished by a relatively small number of men estimated to be at several thousand (the exact number will be established by the new International Commission for Research on Nazi and Soviet Genocide). But the entire process required the willing participation and cooperation of thousands of local authorities and police in various capacities. The role and participation of these "ordinary men" became an issue in many countries after the publication of Charles Browning's book Ordinary Men. Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (New York: 1992). The issue of collaboration, says historian Saulius Sužiedėlis, will be one of the "heaviest and most difficult issues in Lithuanian history that still lie ahead." ("Kas išžudė Lietuvos žydus?" <Who killed Lithuania's Jews?>. Akiračiai 1998/4 <298>, 4-5; see also his "Thoughts on Lithuania's Shadows of the Past: a Historical Essay on the Legacy of War. Part II." Vilnius. Magazine of the Lithuanian Writers' Union. Summer 1999: 177-208). It will be even more difficult because many participants are still alive.

For many years the Holocaust was perceived as a Jewish tragedy. It took almost fifty years for Western European leaders, and even the Roman Catholic Church, to look at themselves in a new way and to acknowledge the wrong they allowed to happen or participated in. In the course of the last ten years, the heads of various governments and churches have issued apologies and offered to make amends. Official commemorative days in honor of the victims were proclaimed in Poland, Germany, France, England, Italy, Sweden and the Slovak Republic. A Holocaust Memorial and Museum has just opened in Berlin, while the one in Washington draws hundreds of visitors each day, changing their perceptions and deepening their understanding of the scope of the catastrophe. After the restoration of its independence in March of 1990, most Lithuanians on both sides of the Atlantic showed an almost complete lack of awareness of this and their own participation in it. The very concept as it is used in the West was foreign to them. When the secret KGB archives were first opened, Lithuanian historians, understandably, turned their attention to the documentation of their own national losses under the Soviet regime. The Jewish Genocide was postponed for almost another decade. As a result, Lithuanians at large are only now getting to the point where they are confronted with a part of their history that had been repressed, distorted and denied for 50 years due to a legacy of silence both in Soviet Lithuania and in the post-war émigré community in North America.

In Soviet Lithuania, as well as in all Soviet-block countries, old prejudices went unchallenged and unexamined and were even reinforced by official anti-Semitism which lasted, with interruptions, until the onset of the reform period set in motion by Mikhail Gorbachev. Synagogues were closed or destroyed, cemeteries left to deteriorate. Even the revered Great Synagogue of Vilnius was leveled. A 1987 travel guide to Vilnius contains no references to the ancient Jewish tradition of the city which proudly called itself the Jerusalem of the North. Soviet-Lithuanian textbooks contained minimal information about Jews and nothing at all about their long history in Lithuania. The blame for war atrocities was ascribed to the fascist regime and fascist elements in the society. A small tombstone at the mass grave at Paneriai (Ponary) did not identify the victims as Jewish. Soviet historians were not allowed to engage in honest research. The KGB was busy monitoring and discrediting the post-war Lithuanian refugees in North America (cf. Arvydas Anusauskas, "Du KGB slaptosios veiklos aspektai." <Two aspects of KGB secret activities). Genocidas ir rezistencija. 1/13. 1998:30-34). As a result, the émigré community developed distrust for Soviet-published sources and dismissed it as "Soviet propaganda". It developed an overall defensive attitude hostile to research. Post-war refugees were for the most part people who had suffered under the Soviet system and devoted their lives and energies to publicizing Lithuania's plight. According to Valentinas Brandišauskas, emigre publications on the uprising and the Provisional Government were for the most part written by former participants and/or former members of LAF or the Provisional Government and presented a reconstructed "romanticized" version of the uprising as an "historic event of outstanding historical significance" ("The June Uprising of 1949," op. cit.). This view is adhered to by the Friends of the Front (Fronto bičiuliai) also known as Frontininkai, gathered around their publication Į laisvę (To Freedom). Members were and still are committed the ideal of a narrowly defined nationalism as opposed to the impending "cosmopolitanism" encroaching from abroad. They are now active in Lithuania and known as "Į laisvę Fondas lietuviškai kultūrai ugdyti".**

According to émigré interpretations, the Holocaust was a strictly German problem. Lithuanians were forced to participate at gunpoint, and those who did were for the most part characterized as "a handful of degenerates" or individuals who had suffered at the hands of Jewish KGB agents and were exacting revenge. The population at large was described as sympathetic and helpful to Jews. Alleged Jewish dominance in the Soviet government and the KGB /NKVD was treated as proven fact. A good example of this type of history is information under the entry "Jews" ("Žydai") in the émigré encyclopedia published in Boston in 1965. (Lietuvių enciklopedija, Vol. 35. Boston: 1966). Any deviations from the accepted interpretation by Lithuanian historians were viewed as influenced by "Soviet propaganda". For the same reason Western scholarship was perceived as biased. Thus the Lithuanian émigré community at large also remained uninformed.

It is to the great credit of forward-looking statesmen in the short formed Sąjūdis Council of 1989 that the government took steps to make amends almost from the start of Lithuania's independence. It also immediately guaranteed the rights of its minorities which were incorporated into the new Constitution on October 25, 1992. Elected as deputies and active in the Sąjūdis Council were two Jewish representatives Grigorijus Kanovičius and Emanuelis Zingeris. Zingeris remained an active member of parliament until recently and is presently heading the new International Commission for Research on Nazi and Soviet Genocide.

The tone for future developments was set during the Founding Congress of the Lithuanian-Jewish Cultural Association in Vilnius on March 5,1989. The keynote address was delivered by Vytautas Landsbergis on behalf of the Supreme Council of Sąjūdis. His address included an apology for the participation of Lithuanians in the Jewish Genocide and emphasized that there was no justification for this crime against the entire Jewish nation. It also added that, as a nation, the Jews had never harmed the Lithuanian people. Last but not least was a plea not to condemn the entire Lithuanian nation.

On May 8,1990, a new Parliament issued a statement of principle. For the first time, in the name of the entire nation, a state institution of the highest order unconditionally denounced the Jewish genocide and pledged to prosecute perpetrators without statutes of limitations. It also pledged support to the Jewish Community and non-tolerance for anti-Semitic manifestations.

Also in 1990, in commemoration of the liquidation of the Vilnius Ghetto in 1943, Seimas declared September 23 an official Day of Mourning. It was decreed that, on that day, the state flag would be marked with a black ribbon and the government would sponsor appropriate events to commemorate the Jewish Genocide. Subsequently, on June 20, 1991, a memorial was unveiled at Paneriai to mark the mass grave of 70,000 Jews killed and buried there. Lithuanian Prime Minister Gediminas Vagnorius delivered an address, again making amends for the crimes of the Lithuanians which cast "such a dark shadow" on the entire nation ("Gedulas ir viltis" <Mourning and Hope>. Lietuvos aidas. 5 July 1991). This established a tradition. From that day on, high government officials have participated in every official ceremony at Paneriai. This year the address was delivered by President Valdas Adamkus.

On September 22, 1994, the eve of the Day of the Jewish Genocide, the new prime minister Adolfas Šleževičius made a statement in which he publicly acknowledged that the number of Lithuanians involved in the executions was greater than a "couple hundred", as heretofore claimed (Kauno diena. 23 September 1994). On February 15, 1995, Parliament passed a law condemning anti-Semitism, xenophobia and other manifestations of intolerance.

In February 1995, Lithuanian President Algirdas Brazauskas made his historic visit to Israel and delivered his famous statement to the Knesset: "As President of Lithuania, I bow my head in memory of the more than 200,000 murdered Lithuanian Jews.... I ask for forgiveness... The Jewish Catastrophe was Lithuania's tragedy as well. It is not enough to apologizewe must constantly be aware of what actually happened. That is our only path to a civilized European world... Let us not forget the past as we direct our gaze toward the future" (Kauno Diena, 4 March 1995).

At home, the President's apology was met with a great deal of criticism. Judging by responses in the press, the official stance taken by the government did not represent public opinion and the President's apology did not have broad public support. While some praised him, many more felt then as even todaythat there have been "enough apologies" and it was time to forget the entire matter. Inconceivably, some voices were raised that the President's apology and admission of guilt reinforced Lithuania's image as a country of war criminals and did further harm to Lithuania's international standing. Even today, a great many Lithuanians continue to cling to the cause-and-effect "two-genocide" theory and believe that the West does not understand their own losses and suffering. Even new research by Lithuanian historians is viewed by some people as "tarnishing" the nation. They fail to see that, in the words of Eidintas, there are no "secrets left" and "what seems new to us is already well known in Western scholarship" (Eidintas, 107) People still have to learn that pointing to so-called "Jewish crimes" is a morally unjustifiable argument which finds little sympathy in the West. It was well put by poet and former dissident Tomas Venclova, "The only way to lessen the crime is to first acknowledge it and then stop complaining that the entire world is conspiring against us, yielding to Communist propaganda or under pressure by international Jewry". ("Nereikia manyti, kad visada esame teisūs" <We shouldn't think we are always right> in Lietuvos Rytas <Lithuania's Morning> 15 July 1993).

The aim of this article is not so much to dwell on the past as to review positive developments at the present toward a true and honest re-evaluation of this painful, suppressed part of Lithuanian history. This movement, set in motion by Landsbergis and members of the Supreme Council of Sąjūdis, is continued by a growing number of people in the Lithuanian intellectual community and is gaining momentum. Its aim is to educate. Historian Vytautas Berenis wrote as recently as last year that to stand up against public opinion and the widely prevalent "mythologized nationalistic patriotism" was an act "requiring moral and personal courage" ("Faktų kalba ir interpretacijos" <Facts and Interpretations>. Šiaurės Atėnai. 24 June 2000). It is becoming less so as more people begin to examine the facts with an open mind and overcome the myths and prejudices which have been whipping up passions and clouding judgment.

In Soviet Lithuania, the wall of silence was first broken by the above mentioned Tomas Venclova on February 18, 1989, with his article "Žydai ir lietuviai" (Jews and Lithuanians) in the weekly Literatūra ir menas (Literature and art). The article appeared just in time before the Founding Congress of the Lithuanian Jewish Cultural Association (Lietuvos Žydų Kultūros Draugija) in Vilnius. The topic was picked up the following year, on January 13, 1990, by Antanas Terleckas, another former dissident, in the article "Once again about Lithuanians and Jews" (Kauno Tiesa <Kaunas' Truth>). Supplementing each other, both authors urged the public to face up to the truth without "national complexes and self-imposed censorship".

In 1990, the Canadian-Lithuanian weekly Tėviškės žiburiai (Beacon of the Homeland) printed a series of articles as a "Lithuanian-Jewish Dialogue", with Lithuanian authors attempting to present the "Lithuanian" point of view. Their interpretations of the massacres at the Lietūkis garage prompted a response by Professor Gražina Slavėnas from Buffalo quoted by Sara Ginaitė (op. cit., 39) : "We deny what cannot be denied, we justify what is unjustifiable. We blame Jews for being vindictive, but ourselves have forgotten and forgiven nothing. The two tragedies are so inextricably linked that we cannot move beyond this "settling of accounts" ("Events in Kaunas through Jewish and Lithuanian Eyes" <Tėviškės žiburiai>. 19 June 1990). The "Dialogue" was discontinued.

In 1991, historian Saulius Sužiedėlis published a groundbreaking article in which he disclosed some of the falsifications perpetuated in the emigre community concerning LAF and the Provisional Government ("1941 metų sukilimo baltosios dėmės" <The 1941 Uprising: its Blank Spots>. (Akiračiai 1991/9-10, 1992/1). On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Holocaust, he discussed the problem in its broader context in Metmenys ("Penkiasdešimčiai metų praėjus: lietuvių tautos sukilimo ir laikinosios vyriausybės istorijos interpretacijų disonansai" <Fifty years later: dissonance in interpretations). Metmenys 61,1991: 149-172). Sužiedėlis established a model to follow for a group of younger historians now actively engaged in research on this topic.

In 1992, Arnoldas Piročkinas, of the University of Vilnius, pointed out that Lithuanians had not yet grasped the full extent of their tragedy: "We should not leave the complications arising from this tragedy to future generations. It is important that we do it ourselves and give our children a solid foundation on which to build decent lives" ( "Kur tikroji žydų tragedijos esmė? <What is the real meaning of the Jewish tragedy?> Kauno Diena, 23 September 1992).

In 1993, The Gaon State Museum in Vilnius, in cooperation with the Lithuanian Jewish Community, organized a scholarly conference to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Vilnius Ghetto. This was the first such dialog in Vilnius between Lithuanian, Jewish and French scholars. The proceedings were published by the Museum in 1995 (Atminties dienos, op. cit.).

In 1993, Lithuanian historian Liudas Truska published his article "Lietuviai ir žydai. Apie vieną gajų mitą" (Lithuanians and Jewsa Tenacious Myth) in which he determined that many so-called "facts" used by Lithuanian authors cannot be substantiated by statistical data: "Unfortunately, nearly everything written thus far about Lithuanian-Jewish relations is not of a scholarly but of journalistic nature and based on personal impressions rather than on facts" (Literatūra ir menas, 24 April 1993). He also added that the stereotype "Jewish KGB agent" is as wrong as that of the "Lithuanian Jew killer". ("Ar žydai nusikalto Lietuvai" <Have Jews Wronged Lithuania?> (Akiračiai 1998/5).

Many Lithuanians firmly believe that most government offices in Soviet Lithuania in 1940-1941 were filled by Jews. Unfortunately, Lithuanian historians have failed to examine the matter in a larger context. In pre-war Lithuania, Jews were excluded from government service, except at the very beginning, and were confined to the private sector only. The new government in Soviet Lithuania proclaimed the principle of equality. Jews and other minorities were actively recruited to join the state power. With the private sector abolished, the majority of Jews lost their economic foundation and their main source of livelihood and were eager to fill the new positions which opened up for them in the public sector. For the intellectuals, after decades of isolation, it was an opportunity to play a role in the public, political and cultural life of the country. A Jewish section was formed within the Writers' Union. Many appreciated the prestige that went with the office. To many Lithuanians who had never seen a Jew in any state office, it now appeared that all official positions were filled by Jews. This generated even more anger and resentment and strengthened the public opinion that Jews were the major supporters of the new regime. It also led to a new type of competition for government jobs. Labels of a "Jewish government" arose form personal perceptions rather than facts. Lithuanians find it just as hard to acknowledge that Jews too were subject to Soviet political persecution.

The Jewish Community during the first Soviet occupation was very hard hit. Contrary to popular belief, it suffered disproportionately higher losses economically and politically than the Lithuanian population. Nationalization of industry, trade, transport and other private enterprises destroyed its economic foundation and sources of income. Hebrew was banned and all Jewish political, religious, cultural, educational, and charitable organizations were closed.

Most Jews were deeply religious people. Political repression of Jewish religious and community leaders is demonstrated by a top secret 20-page report "On the Counter-revolutionary Activities of Jewish Nationalist Organizations" dated March 29, 1941, to authorities in Moscow by Piotr Gladkov, Head of the Security Commissariat (NKGB) in Soviet Lithuania. According to this report, at the end of 1940, the NKGB was successful in crippling anti-Soviet activity by "Jewish counter-revolutionary organizations" with a "strong operative blow against their most active head units". This indicates that the NKGB was waging a specifically anti-Jewish campaign as early as the end of 1940. Eighty-nine Zionists and Bundists were arrested (Lietuvos ypatingas archyvas (Buvęs LTSR KGB archyvas). Fondas K-l. Apyrašas 10, Byla 4. Lapai 179-198).

The report also shows that by March 1941, 1,423 leaders of Jewish political and religious organizations were under investigation. Jewish organizations under suspicion in Vilnius and Kaunas included right-wing Betar and left-wing Hashomer ha-Tso'ir Zionist organizations, all accused of counterrevolutionary activities. The report lists names of people who were active in synagogues and yeshivas and were urging Jews to remain loyal to their faith and traditions and to view Soviet rule in Lithuania as temporary (ibid.). Many of the people named in the report were arrested and/or deported in June 1941. Ironically, the Jews in Siberia had at least a chance for survival. Gradually more and more information is becoming available on the life and demise of Jewish communities in smaller towns and cities.

In 1995, journalist Rimantas Vanagas published a book called Nenusigręžk nuo savęs (Don't turn away from yourself. Vilnius: 1995) with an account of the murder of 2,000 Jewish inhabitants in the town of Anykščiai at the hands of their neighbors. Among the dead was the highly respected physician N. Ginzburg. Writer Antanas Salynas published an even more heart-wrenching account about 1,800 Jews killed in Jurbarkas, and the destruction of an architectural masterpiece, a hand-carved wooden synagogue erected in 1790. (Nužudytų vėlės budi," <Dead Souls are Watching> Kauno Diena. 7-8 August, 23 September 1996). New research by Bubnys sheds additional information on the creation and liquidation of many other small Jewish ghettos across Lithuania. (Arūnas Bubnys, "Mažieji Lietuvos žydų getai ir laikinos izoliavimo stovyklos 1941-1943 metais"<Small Jewish Ghettos and Temporary Isolation Camps 1941-1943> Lietuvos istorijos metraštis 1999. <Yearbook of Lithuanian History 1999>. Vilnius: 2000).

In 1996, Liudas Truska published his research on the Russification of Lithuania's official institutions in 1940-1941 ("Lietuvos valdžios įstaigų rusifikavimas, 1940-1941". Based on archival documents of the Central Committee of the Lithuanian Communist Party, Truska's research shows that most positions in the KGB/NKVD and other repressive state structures were filled by ethnic Lithuanians and top positions were assigned not to Lithuanian Jews but to thousands of Moscow-sent Russians, Byelorussians and Ukrainians from the Soviet Union. "In all sectors, a Lithuanian served as the head, and a foreigner sent from Moscow, mostly Russian, as his assistant". (Darbai. Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo institutas. Proceedings. Lithuanian Research Institute on Genocide and Resistances V. 1996: 3-2.8).

According to Truska's research, in 54 towns and districts, no Jews served as chairmen or their assistants in executive committees. Among 279 secretaries and department heads there were 17 Jews (6%). There were 20 Jews (7.1%) among the 279 members in the NKVD People's Commissariat; two Jews (4.5%) served among a total of 44 as NKVD department heads or assistants in 22 towns and districts; 36 Jews (13%) among 285 in authority positions in the NKGB (Security Commissariat); and none among the 44 NKGB department heads or their assistants in 22 towns and districts. The majority in the party and in the state security apparatus were 2,184 Lithuanians (46.4%); 1,926 Russians and others (41%); of these 1,500 (29%) were sent by Moscow.

In the KGB/NKVD, positions of power were held by a total of 918 individuals, among them 70 (7.6%) Jews, most of these from outside the country. Lithuanian Jews in key positions were Danielius Todesas, Special Section Chief, Eusiejus Rožauskas, Interrogation Section Chief; Aleksandras Slavinas, Special Assignments. Active Jewish Communists in the party apparatus did not exceed a total of 1,000. This is a tiny fraction of the total Jewish population and in no way represented or reflected its position or aspirations. The number of Jews who were politically repressed is higher than that of the Communist activists. It must be noted that committed Communists did not hesitate to turn against their own people, knowingly destroying the Jewish elite and Jewish religious and cultural heritage in the name of their ideology. They brought great shame on themselves and the Jewish Community and should be brought to justice. But to make the entire community responsible is legally and morally not justifiable.

Research also shows that Soviet authorities did not trust Jewish Communists in the Party. During party purges, Jews became special targets. Many former underground party members were forced to resign for their non-proletarian background or prior affiliations with Zionist or other "foreign" organizations. Jewish membership in the Party was disproportionately high in 1940, but by June of 1941, it had dropped significantly. Of a total number of 4,703 members, only 593 were Jews.

In 1997, professor Alvydas Nikžentaitis, present president of the Lithuanian Historical Society, organized a conference in Nida in which Jewish historians participated. This helped bring to light more information and differing points of view. Slowly, more and more Lithuanians are beginning to comprehend that the Holocaust is also a Lithuanian tragedy. The burden now falls heavily on the shoulders of generations born after the war.

On October 8-9, 1998, the Lithuanian Catholic Academy of Science in cooperation with the Vilnius University and the Lithuanian History Institute organized a conference on the theme of Catholic Church in Lithuania and the role of the Lithuanian-Jewish relations in the 19th-20th century. Papers presented discussed religious anti-Jewish prejudices in historical perspective and touched upon the role of the Lithuanian Catholic Church during the German occupation and the Holocaust. A special attempt was made to list the names of individual priests who disregarding official Church policy took the initiative to shelter runaway Jews. These papers are now available in the Vol. 14, 1999 Academy's Yearbook Lietuvių Katalikų Mokslo Akademijos Metraštis.

An unexpected event of far-reaching significance, which may forever change the previous direction of the Roman Catholic Church and have a profound effect on forming the mindset of a new generation of Roman Catholic Christians around the world was the famous document We Remember: Reflections on the Shoah, issued on March 12, 1998, by Pope John Paul II and the Vatican hierarchy. With this document, the Church in essence acknowledged its role in the creation and perpetuation of anti-Jewish stereotypes, especially the deicide and blood-libel myths, which were well-known in pre-World War II Lithuania. The demonization of Jews by Christians had for centuries kept Jewish communities isolated from Christians as an alien and dangerous people and justified the terrorization of Jewish communities by Christians in many countries, beginning with the Crusades and continuing through the Middle Ages into modern times. This mindset prepared the ground for the easy spread of Hitler's political and racial persecution and ultimately the Shoah. The Pope reiterated his repentance and apology during the unprecedented papal visit to Jerusalem in May 2001. On April 14, 2000, the Lithuanian Roman Catholic Church hierarchy issued its own Apostolic Letter denouncing the policy of silence and urging the faithful to enter the new century in a spirit of repentance and with determination not to repeat old sins. The core of the letter deals with the Holocaust. The Church publicly admitted its regrets that "some of its children" during the Second World War placed "nationalistic egotism" above the teachings of the Gospels and were lacking in "Christian love" for the persecuted Jews and lacking resolve to "influence those who assisted the Nazis in their gruesome task". The Church also added its concern about continued manifestations of anti-Semitism. The letter was signed by Archbishop Sigitas Tamkevičius, President of the Lithuanian Conference of Bishops, and Bishop Jonas Boruta, JS, Secretary General. On April 15, 2000, the Lithuanian Roman Catholic Church also observed a "Day of Penance and Pardon" at the Vilnius Cathedral ("Letter of the Bishops", "Conference of the Bishops", Jerusalem of Lithuania 2000/3-4).

Disregarding all these significant developments, on August 12, 2000, enough members of the Lithuanian Seimas voted to pass a law to honor the 1941 anti-Soviet uprising by declaring it an official Day of Remembrance and legitimizing the restoration of Lithuanian independence proclaimed by the Provisional Government on June 23, 1941, thus also legitimizing the Provisional Government. Passage of this law indicates a glaring lack of sensitivity if not outright ignorance among members of parliament who voted for it, presumably in the name of nationalistic pride and patriotism. June 23, 1941, of course, coincides with the outbreak of the German-Russian war and the beginning of the Jewish Holocaust in Lithuania, which the Provisional Government facilitated. It was good to note that passage of this law resulted in an immediate outcry of indignation by many members of the Lithuanian intellectual and academic community and signed protests from numerous civic organizations, the House of Memory, the Lithuanian-Jewish Community and others. President Adamkus called it a disgrace, indicating a serious gap in awareness among certain segments of the population. Parliament immediately repealed the law, but the harm was already done and there was another round of negative repercussions abroad.

It is not the intention of this paper to discuss the role of the Provisional Government in the destruction of Lithuanian Jewry. Thorough research is being conducted by Lithuanian historians. The falsifications and omissions in the writings of former members of LAF and the Provisional Government have been exposed. Repeated declarations by Juozas Ambrazevičius-Brazaitis, that the August 1 Decree on the "Jewish Situation" was a Soviet fabrication have also been proven untrue. This and other documents and other originals, edited by historian Arvydas Anusauskas, have been reprinted by the Lithuanian Center for Genocide and Resistance Research in Vilnius, in 2001. Until the creation of the Ostland government, the Provisional Government functioned as a more or less legitimate government and was tolerated by the Nazis by obligingly passing its anti-Jewish measures. According to Brandiškauskas, its stance was "anti-Communist and anti-Jewish" ("The June Uprising of 1941," op. cit.). It has been claimed by its supporters that the Government acted under duress and did all it could to help Jews. This is a very lame argument. The Government knowingly passed laws which placed Lithuanian Jews outside the law and provided German authorities with a Lithuanian-made legal framework to implement their own progressively more deadly policies. Nazi leadership at that time was still concerned with preserving its image by having Lithuanians do the dirty work. Thus there was some room to maneuver. Yet the Provisional Government made no attempt to stop, punish or condemn the ongoing executions, not even at the end of its existence. A protest would have provided the disoriented country with some guidance and moral example. Instead, by encouraging hundreds if not thousands of young men, including patriotic resistance fighters, to sign up for service in the auxiliary police battalions, it facilitated their becoming drawn into their murderous tasks. Its legislation and propaganda in effect exonerated actual and potential murderers from any moral or legal responsibility. Only a few of the original LAF members were members of the Government, which was controlled by Christian Democrats, but the consistently virulent anti-Semitic propaganda in its publication Į laisvę demonstrates that most members shared the ideology as it was first proclaimed by the LAF Center in Berlin. The various writings by former members demonstrate unconcern for the fate of the Jewish population. Last but not least, it must be kept in mind that it was not recognized by any other country or even by the Lithuanian diplomatic Corps in Exile. President Smetona in U.S. exile denounced it in the Lithuanian-American press. It needs mentioning that members of the above mentioned Fronto bičiuliai (Friends of the Christian Democratic Front) are now active in Lithuania and have been petitioning the Lithuanian government to recognize the significance of the 1941 uprising by legalizing the Declaration of Independence proclaimed by the Provisional Government on June 23, 1941. During their Studies Conference (Studijų Savaitė) this summer (2001) in Trakai, members and supporters of the Front continued with their interpretations in the name of nationalism and religion. Zenonas Rekašius, editor of Akiračiai, makes a strong point that it is detrimental for Lithuanians to identify the uprising with the Provisional Government and that it would be more honorable for former participants to acknowledge the errors of the past and not mislead the entire country with their self-serving interpretations ("1941 metų satelitinės Lietuvos valstybės modelis" <The 1941 Model of Satellite Government> Akiračiai, 2001/9).

Many of the present positive developments have taken shape during the administration of President Valdas Adamkus. A very important step was the creation of the new government-sponsored International Commission on Nazi and Soviet Crimes in Lithuania (Tarptautinė komisija nacių ir sovietų nusikaltimamas Lietuvoje įvertinti). Numerous conferences with international presenters have been taking place and serious research is conducted by historians at the Lithuanian Center for Research on Genocide and published in its journal Genocidas ir rezistencija.

At the invitation of the Lithuanian government, an International Forum on the restoration of Holocaust looted property was held in Vilnius on October 4-5, 2000. The event was a continuation of previous conferences held in London in 1997, Washington in 1998, and Stockholm in 2000. Representatives from 40 countries and dozens of international organizations attended the Vilnius Forum, which passed a resolution acknowledging the mass theft of personal and cultural items. The Lithuanian government has turned over to Jewish religious communities an invaluable Tora collection safeguarded at the national Mažvydas Library. This was very well received.

Jews and Lithuanians work together in trying to locate and honor individuals and families who offered charity and refuge to persecuted Jews. The penalty for hiding Jews for "compassionate reasons" was death, and it was often carried out instantly to discourage others. The exact number of Lithuanians killed or punished is still unknown, but a search is underway. To hide a runaway Jew, one family was seldom sufficient. It often necessitated a community of people working together in utmost secrecy. Many of them have been hesitant to come forward even after the war. According to verified data collected at the Jewish Gaon State Museum in Vilnius, about 2,300 families have already been positively identified. About 3,000 Jews were saved, among them many Jewish children, and some are active on Lithuanian behalf. Professor Irena Veisaitė, long-term President of the Open Society in Lithuania Foundation, is one of them.

The first "Righteous among Nations" awards were awarded in 1953 to Ona Šimaitė, Julija Vitkauskienė, Sofija Binkienė and others. The first book was published by Philip Friedman in New York and Vilnius in 1957 (Their Brother's Keepers. New York: 1957; Mūsų brolių gelbėtojai. Vilnius: 1957). Sofija Binkienė succeeded in publishing the first and for a long time only collection of names Ir be ginklo kariai <Unarmed Soldiers>. Vilnius: 1967). However, further research was frowned upon by the Soviet authorities.

After Lithuania's independence this matter was a high priority of the Jewish Community. Numbers are changing and new award ceremonies are taking place all the time. To date, the Yad Vashem Institute has awarded about 400 Lithuanians with the title of the "Righteous among Nations", and the Lithuanian President has honored more than 300 persons with the "Rescue Cross". The important work of finding and honoring these brave people or their descendants is being carried on to this day.

The Jewish Gaon State Museum started publishing a serial publication Gyvybę ir duoną nešančios rankos (Hands bringing Bread and Life), compiled by Viktorija Sakaitė, with Mikhail Erenburgas and Dalija Epštaineitė (Vilnius: 1997; 2001). Viktorija Sakaitė published an article on Lithuanian priests and nuns who hid Jews. (Žydų gelbėjimas" <Rescue of Jews>. Genocidas ir Rezistencija. 1998 2-4). The latest book (Išgelbėję pasaulį <Saving the World> Vilnius: 2001) was compiled by Dalia Kuodytė, President of the Lithuanian Center for Research on Genocide, and Rimantas Stankevičius. According to verified records, 3,000 Jews were rescued.

These are indeed the "Golden Pages" of Lithuanian history. Nevertheless, it is a historical falsification to claim that most Lithuanians were helpful or even sympathetic to Jews, as presented in a high school textbook by Juozas Pumputis published in Vilnius in 1995. The book skims over the Holocaust and conveniently sums it up with a statement about "Jewish rabbis expressing special gratitude to Lithuanians for their compassionate help"! (Lietuvos istorija <Lithuanian History>).

Linas Vildžiūnas, editor of Septynios Meno Dienos, founded the House of Memory. At the Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, the "Sugihara Center" sponsors research and cultural activities. The young filmmaker Saulius Beržinis has released a new documentary Sunset in Lithuania, based on many hours of interviews with eye witnesses and survivors. Educators and journalists are getting involved in projects raising awareness and fostering tolerance. For young people, preparations are underway for a nationwide program of Holocaust education in schools.

A wide variety of publications on the Holocaust, both original and in translation, have become available, many of them sponsored by the Open Society Foundation. Books by survivors are being translated into Lithuanian. Author Markas Zingeris compiled selections from Yiddish literature and published an anthology (Šiaurės gėlės <Northern Flowers> Vilnius: 1997). Theater director Rimvydas Tuminas won numerous international awards for his stage adaptation of novels by Gregorijus Kanovičius "Nusišypsok mums, Viešpatie" (Smile at us, Lord). Cultural and musical events and concerts by Jewish performers have attracted large audiences. Poet Sigitas Geda put together an anthology of selected poems on the Holocaust by Lithuanian poets. The best Lithuanian poets writing at that time responded to the Jewish tragedy as soon as censorship relented, at about the same time as the Russian poet Evgenyi Evtushenko published his famous poem "Baby Yar". Among them were Justinas Marcinkevičius, Vytautas Bložė, Janina Degutytė, Judita Vaičiūnaitė, Violeta Palčinskaitė, Alfonsas Bukontas. The anthology also includes poetry by emigre poets. (Mirtis, rečitatyvas ir mėlynas drugelis. Lietuvių poetai apie Holokaustą. <Death, Recitations and a Blue Butterfly. Lithuanian Poets about the Holocaust>. Vilnius: 2000).

At the University of Vilnius the Center for Stateless Cultures has been established under the direction of Dovid Katz. Professor Katz himself is involved in collecting and analyzing remnants of Yiddish language and culture in Lithuania and Belarus and teaching Yiddish and Judaic Studies at the University of Vilnius. As a result, there is an upsurge of interest among the younger generation to learn about the lost Litvak culture. In this context, it is well to remember that we are talking here merely about resurrecting and preserving a heritage of the past, remnants of a once great culture. In the words of Vytautas Landsbergis, neglecting preservation of the Yiddish heritage would be tantamount to a "second, spiritual holocaust" ("Galime ir turime neleisti" <We cannot and will not allow it> Lietuvos Jeruzalė. 1995/3-54). Yiddish is now taught at universities as a dead language.

A remarkable event this summer was the first Litvak Conference on August 24-30, 2001, organized by the concerted efforts of the Jewish Community in commemoration of this anniversary. It was attended by about 300 people with Litvak rootslitvakesfrom all around the world and offered a rich historical and a cultural program. The opening took place at the Vilnius City Hall and was attended by high government officials, foreign ambassadors, politicians and several hundred Lithuanian and foreign intellectuals and academics. The opening address was delivered by President Adamkus. Other distinguished speakers were Prime Minister Algirdas Brazauskas, Seimas Speaker Artūras Paulauskas and the newly appointed Ambassador to Israel Alfonsas Eidintas.

All these are welcome new trends indicative of a new spirit on all sides to come together and establish a mutually productive dialog. Among the stereotypes and prejudices that have plagued Lithuanian-Jewish relations is also that of "collective guilt" perpetuated by extremists on both sides. Ilja Lempertas made the point last year that no public: official in Israel has accused the entire Lithuanian nation or demanded any apologies. This is also the position of the Jewish Community in Lithuania, as repeatedly stated by its president Simonas Alperavičius.

As in all post-Communist countries, newly acquired independence led to at first an idealization of their pre-World War II, pre-Communist history but then also, painfully, an examination of their role during the war toward their Jewish minorities. Open debate of this most sensitive issue progresses slowly. It has come furthest in Poland. In Lithuania it has just begun.

I would like to end with the words of Irena Veisaitė at the International Forum in Stockholm in January 2000: "Attitudes and judgments change slowly. But the process of building bridges has begun. Dialogue and mutual understanding require time and good will on both sides." ("Tam reikalui būtinas laikas ir gera valia" Lietuvos Jeruzalė, 2000/ 1-2).

*

Dr. Solomon (Solomonas) Atamukas is the author of Lietuvos žydų kelias. Nuo XI amžiaus iki XX a. pabaigos (The journey of Lithuanian Jewry from the llth to the end of the 20th century). Vilnius: Alma

Littera, 1998. A shorter version has appeared in German as Salamon Atamuk, Juden in

Litauen. Bin geschichtlicher Überblick (Jews in Lithuania, A Historical Survey).

Konstanz: Hartung Gorte Verlag, 2000. For any clarification, please consult these publications.

The above article was adapted and translated for this issue from Lithuanian into English by

M.G. Slavėnas.

** Editor's note: This group, although vocal, did and does not represent the entire emigre community. No less active was the emigre association Santara-Šviesa, founded in 1957, which fostered open discussion among intellectuals and academics on controversial subjects in its annual conferences and supported the publication of the biannual Metmenys (Outlines) edited by the late Vytautas

Kavolis, presently by Violeta Kelertas and Rimvydas Šilbajoris. This association lists among its members persons who have reached prominence in Lithuanian affairs, foremost among them Lithuania's present president Valdas Adamkus and his advisors Raimundas Mieželis and Julius Šmulkštys. Its members are also associated with Metmenys and Akiračiai and have been serving on the executive board of AABS (Association for Advancement of Baltic Studies). An early article on the present topic was published in Metmenys by Julius Šmulkštys ("Mitai ir Lietuvos išlaisvinimas" <Myths and Lithuania's liberation). 11/1996: 293-294). A session on the Holocaust in Lithuania was organized by Romas Misiūnas during the 1978 of AABS in Toronto.