Editors of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

Copyright © 2002 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 48, No.1 - Spring 2002

Editors of this issue: Violeta Kelertas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 2002 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

LOOKING TOWARD THE FUTURE,

THINKING ABOUT THE PAST

The Career Influences and Recent Work of Rimas VisGirda

CATHERINE JACOBI*

The phenomenon of seeing a piece of art more distinctly the further one steps back from it is the equivalent of understanding a homeland from the singular viewpoint of the foreigner. Both equations are distances, measuring the vantage pointone by the realization of phenomena, the other by the memory of it. A comparison by perspective, like the artist's outstretched thumb in the airboth shaped, given dimension by way of experience.

I, for one, know of no sweeter sight for a man's eyes than his own country.

Homer, Odyssey, tr. Rex Warner

A tour of Russia in 1988, as an exchange artist with the Soviet Artists' Union, routed Rimas VisGirda briefly to Vilnius, Lithuania. It was to become the first of many trips to the country he was born in and later fled from with his parents in 1944. VisGirda spent his formative years on both American coasts (Boston and Los Angeles). He accepted a series of Midwestern teaching positions from Bemidji to Des Moines and covered thousands of miles throughout the United States and abroad as a visiting ceramist. As odysseys go, it seems the traveler never really knows from where he is navigating, and the observer can only summarize by connecting the points. For VisGirda, this trip to Lithuania could have become just another point of departure, leaving the idea of beginnings or endings to fate. VisGirda, in the tradition of the traveler, understood that his traveling was necessary if he was to find meaning in his experience as an artistthe rare sort who knows his homeland only as nostalgia. And more importantly, this first return home would continue to be a powerful influence on his work almost a dozen years later.

Lithuania was a foreign idea in the midst of 1950s California kitsch. VisGirda describes himself during this time as the kid on the block with the open-toed sandals and the funny name. He had a unique American experience, for the most part unrecognized, during an overtly homogeneous postwar American attitude, he recalls an upbringing of primarily European influences. From the time of his departure from Lithuania, its language and culture were carried on and maintained at home in America. While assimilating, VisGirda recalls detaching himself from his family. To compensate for his foreignness he often overstated his Americanness.

In 1966, VisGirda finished his studies in Physics at California State University, Sacramento. After a brief career as a physicist, and a partner in a pottery in the Sierra foothills, he returned to the university to complete a graduate degree in Ceramics and Sculpture. Heavily influenced by these technological and scientific studies, VisGirda's first bodies of work dealt with basic ideas of pottery and process and were soon influenced by the narrative work of his mentors, Ruth Rippon and Robert Arneson. Rippon was a master at surface enrichment, utilizing sgraffito, sgraffito through engobe, wax resist and general surface decoration. For the most part, the work was high fire, porcelain or white engobe over stoneware, colored by oxides. A method of sketching on the engobe, filling in the color, waxing the entire piece, sgraffito the holding lines through the wax and then filling the lines with a heavy black engobe, gave way to experimentation. To introduce more vibrant color, he used the lusters and commercial colors that Arneson was using. This was a pivotal moment for VisGirda who, armed with this technique, began to wrestle with the weighty possibilities that Arneson introduced through his personal vision and emotive consequence. Themes from VisGirda's American experience began to reveal themselves on the surfaces of his vessels. Stylized, comic-style drawings with characteristic heavy black outlines, pulled from the dark influences of Crumb, Moscoso and Spain, captured an everyday existence. Challenging urban themes emerge via stockings, garters, empty cans and cigarette butts. More comfortable dialogues on American domesticity were debated through subjects like big dogs, anonymous women and voluptuous trucks. Titles like How Come My Dog Don't Bark When You Come Knockin' on My Door align with American country music or blues, and he often plays on the simple fulcrum of a cliche. This technique, subject matter and path of intent would serve VisGirda as a groundwork for variations and refinement for the next twenty years. Themes that fall nothing shy of coincidence and technical difficulties would necessarily be rethought.

Take away the cause, and the effect ceases; what the eye ne'er sees, The heart ne'er rues.

Cervantes, Don Quixote, tr. John Ozell

In 1989, the year after VisGirda's first return to Vilnius, he was invited to attend the First International Ceramics Symposium in Panevėžys. A small city of 100,000 in central Lithuania, Panevėžys was industrialized by the Soviets, specifically with a glass factory. At the time of this first invitational symposium, political protests in the country were still mounting, because Lithuania had not yet attained her independence from the Soviet Union. In the late eighties, visas and invitations into the country were not easy to come by. In fact, VisGirda and his colleague Phil Cornelius (the first Westerners to visit Panevėžys) received their papers only days before the event began.

The symposium (originally a ceramics seminar for local artists) invited, in all, sixteen artists to participate: six from Panevėžys, six from Vilnius (the capital of Lithuania), one from Moscow, one from Hungary, and two (VisGirda and Cornelius) from the United States. The artists worked for five weeks, using the city's glass factory during the summer holidays for clay and kilns. The finished work was curated into an exhibition, and selected work was first exhibited and later donated to the Panevėžys Civic Art Gallery. The gallery's director, Jolanta Lebednykienė, with the help of VisGirda, would eventually organize and develop this event into an annual symposium. In the following years, and as the country's politics changed and expanded, the symposium also expanded to host a broad spectrum of international talent.

Before processing what the unique cultural, social and psychological influences of being in Lithuania meant, or how these things would impact his work, VisGirda was abruptly brought back to everyday logistics. The size of the industrial kiln, (2 meters high x 3 x 4 meters, and firing at 1380°C), would be too large for his small vessels and too hot for his low-temperature technique. Therefore, creating large work became a practical necessity. The previous year he had been moved by the huge Soviet political sculptures he had seen, but the idea of sizeof sculpture versus vesselhad not yet revealed itself in his work.

A clear advantage in working in a larger scale was the ample supply of clay available at the factory. Unique to Eastern Block ceramics is a clay called Chamotte, which is a heavily grogged stoneware that vitrifies at Cone 13. VisGirda found the Panevėžys clay to have amazing strength and to be ideal for coil construction. The factory clay was brought in for the symposium by train from Ukraine. Half the quantity was fired (for as long as a week) to Cone 11 and then ground into various sizes of grog. The other half was pulverized, resulting in a white clay containing 40-60 percent grog.

Besides the physical necessity of making larger works, VisGirda had to reconcile how he could incorporate his repertoire of images, given the abundance of both space and cultural iconography. Pickup trucks were not an obvious part of the Lithuanian landscape. The overwhelming variety of religious and political symbols began to make their way into his pieces. VisGirda did this in the same way a foreigner, who is not quite foreign, creates a Creole of interpretations. Religious figureslike birds, snakes, the sun and moon, and oak trees originating from pagan symbols, but often translated into Catholic ideology and suppressed by the Soviets became powerful additions to his hybrid iconography.

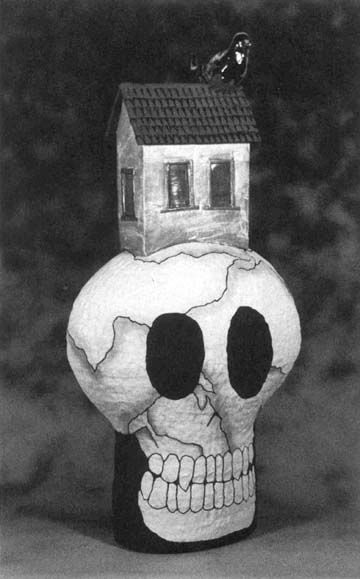

During the summer of 1989, the Soviets returned the bones of exiled Lithuanian intellectuals from the furthest points of Siberia. This intense political act moved VisGirda to incorporate bones as a symbol of change into his work. Portraits of Lenin, Stalin and other political figures that would soon become mere remnants of Soviet propaganda also found their way into this first body of work, by way of drawings, military medals, and sculptured busts. In the piece entitled Hope a huge skull with the world mapped on its surface reinforces the idea of loss, while it supports a simple house upon which a solitary bird is perched. The skull is cavernous. Eye sockets mirror the two unassuming windows on the modest house. VisGirda explains that the bird, transferred from Lithuanian iconography, where it occupies the space between heaven and earth, represents for him hope, dreams and the future.

It is possible to look beyond coincidence, then the distance of that looking becomes profound. With his footing in a homeland that was itself struggling to reclaim its own identityessentially VisGirda's cultural identityreferenced Lithuania as a familial habit, as he himself would be compared with its origins. A language he learned in a familiar way is lacking in a life outside of his upbringing and a 50-year lapse during which the country was forced to submit to an official Russian language. In a fateful way, VisGirda's personal references and the country's united aspirations coincide with a time before the Soviet invasion, and again at the beginning of independence.

VisGirda and his country, both in search of their Lithuanianness after years of suppression, prove to be an overwhelming bounty of inspiration: culturally, socially and psychologically. A heavy realization, impossible to forget or ignore even after leaving it.

It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.

Saint-Exupery, The Little Prince, tr. Katherine Woods

Since his first return in 1988, VisGirda has visited Lithuania six times. He is by self-proclamation an "official born-again Lithuanian." His association with the symposium since its beginning in 1989 has helped it to become a successful annual international event. His contacts because of and on behalf of the symposium have helped to promote a prolific exchange of artists to and from Lithuania.

In October 2000, VisGirda exhibited his most recent work at the Lithuanian Museum of Art (Lietuvių Dailės Muziejus) in Lemont, Illinois, a facility dedicated to promoting Lithuanian art and an adjunct to the Lithuanian World Center, a cultural and educational facility. Several pieces from the exhibition were selected for the Lithuanian Embassy Gallery in Washington, DC. for an exhibit from January 14 through the month of February, 2001.

The exhibition is a combination of transitional works those pieces incorporating a new iconography and technique and the next generation of these influences. The new work expresses a further resolution and refinement. The transitional pieces, dating from 1997 to earlier this year, continue with bold themes of personal horror by way of dark comedy. This work is more intimate in size and more focused on internal struggles than the social heroism of Hope. In pieces like Conversation, ominous masked heads with riveted patches covering every identifiable feature are brought to submission by the presence of a bird. The allegory of generations is leveled in Like Mother like Daughter. A single torso that balances two hooded heads triggers the same sense of caustic irony by way of a cleavage. Almost 8, poses a precarious notion of balance with the "7" billiard ball and hooded figure. Serious cultural divisions and social complexities are illustrated with VisGirda's hooded anonymous figure, who guards a piece of amber (particularly abundant and of excellent quality in Lithuania) that is worn at its heart. These ominous qualities are enhanced by singed smoke patterns, the product of a technique VisGirda refers to as charcoal firing. These characters are the evident remains of a struggle and serene submission. VisGirda presents us the realm of the absurd, a dark comedy inspired by the aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union and the constant reminder of our futile attempts to outwit our own nature.

Earlier this year, VisGirda began a body of work that sidesteps the awkwardness of having a foot in two places. Heroic busts and political irony give way to human poignancy. With the familiar idiomatic titles like Mamas, Don't Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Cowboys VisGirda gives us an insight into the pride of the character by way of a slightly turned head, a subtlety not possible in surface

drawings. The influence of the heavily grogged Chamotte from Lithuania is referenced by the use of a feldspar grog, a decomposed granite with glass-like bits that break through milky surfaces. While these figures carry some surface decoration, it is secondary to form. The importance of vessels versus pottery has diminished in these pieces behind a strength of character. The obligatory exhibition of technique and familiar graffiti signature remain only in subtle surface patterns with soft colors and a few commercial decals applied to the backs of the works. The decals function much like the titles of these pieces: as a point of departure meant to defuse the undeniable seriousness of human nature.

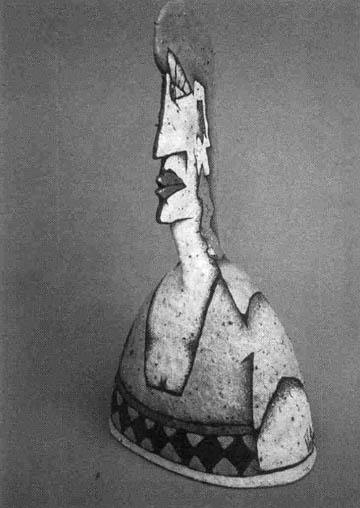

In There's Two Sides to Every Woman and Updraft Vis-Girda's earlier Every Woman character, who once represented sexuality and vitality, is remodeled into melancholy-on-its-way-to-dread. VisGirda's blue-eye-shadowed women look into the distance from a point of passing style and weighty expression. More philosophically charged, Looking Toward the Future, Thinking about the Past is a double figure that shares a torso and the brim of a hat and defies the definitions of front and back, hinging on the prospect of an infinite continuum.

While personal in nature, these pieces are not memoirs. They are instead realizations of the power of subtlety and the intimacy of universal expressions. But they still maintain the ultimate realization of the human conditionin which we all eventually do get home.

* Catherine Jacobi is a designer and partner at Ted Studios in Chicago.

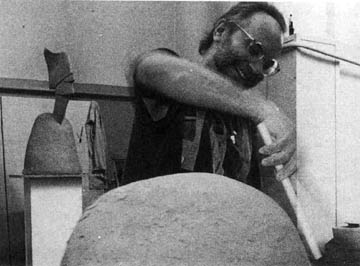

Photo: Sergejus Kašinas

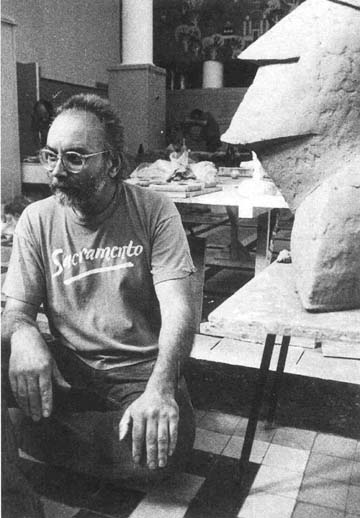

Rimas Visgirda working in the First International Panevėžys Ceramic Symposium, 1989.

"Melony and Dorothy", 11.5 " diam. x 21.5"

"Home is where the heart is", 112 " diam. x 1.5", stoneware, 1980's.

Rimas Visgirda working with Chamotte clay in LSSR First

International

Panevėžys Ceramic Symposium, Panevėžys , Lithuania, August 1989.

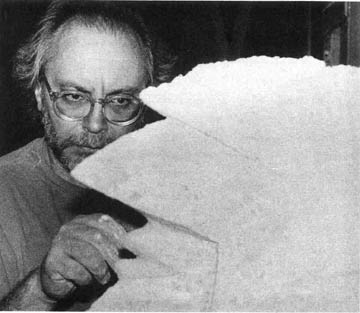

Rimas Visgirda working with Chamotte clay in LSSR First

International

Panevėžys Ceramic Symposium, Panevėžys , Lithuania, August 1989.

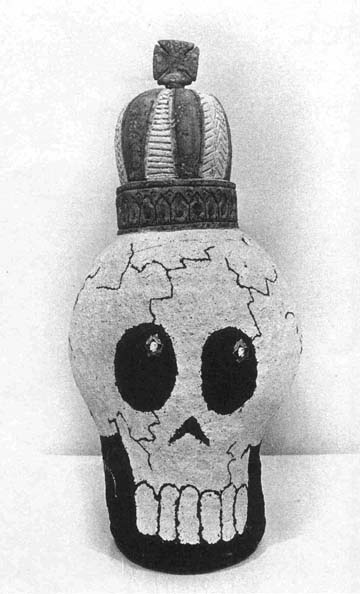

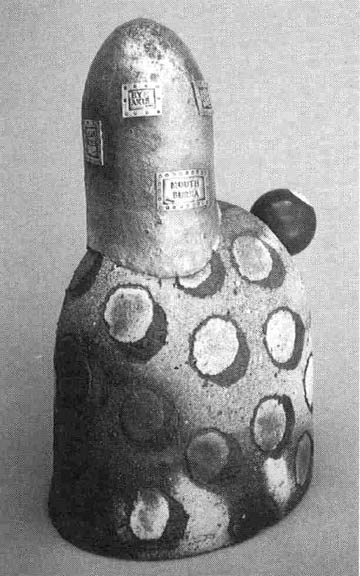

"The King", 49.5 cm high x 28cm x 13 cm.

First International Symposium, Panevėžys , Lithuania, 1989.

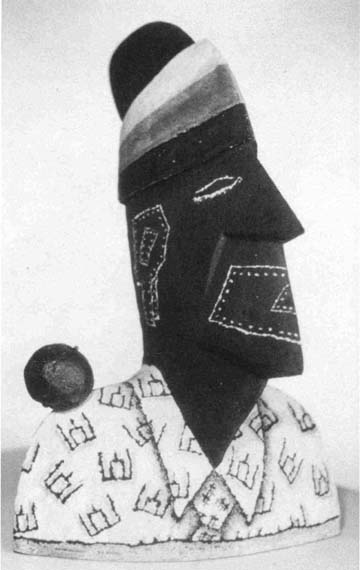

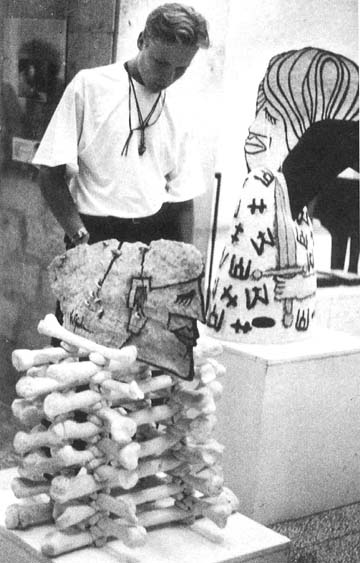

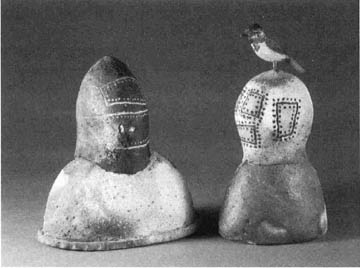

Work created at Panevėžys Ceramic Symposium, 1989.

"Rimas Visgirda at Panevėžys Ceramic Symposium, 1989.

"Hope", 60" high x 28" x 19 ".

"Fourth International symposium, Panevėžys, Lithuania, 1992.

Pieces in exhibition at Panevėžio dailės galerija.

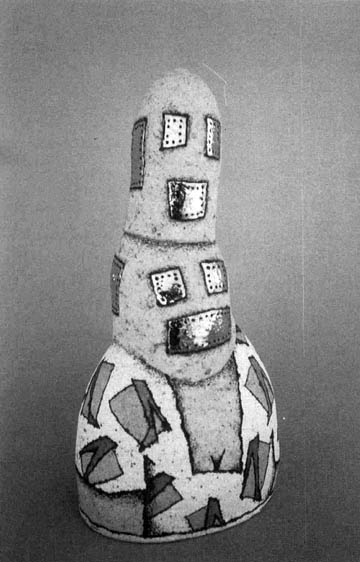

Foreground: "Three years in the making", 80 cm high x 60 cm x 45 cm.

Background: " First year man", 112 cm high x 50 cm x 54 cm.

"Almost 8", 14" high x 8" x 6", stoneware, charcoal fired, billiard ball, silver, 2000.

"Conversation", 12" high x 11 x 7", 1997.

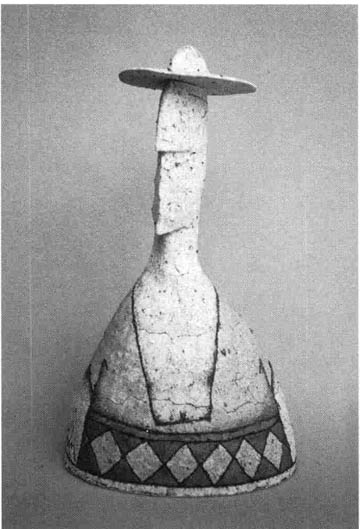

"Mamas don't let your babies grow up to be cowboys", 16.5" high x 9.5" x 6.5".

"There''s 2 sides to every woman", 19" high x 10" x

8",

"Updraft", 23" high x 11" x 8".

"Looking toward the future thinking about the past", 2000, 15" high x 11" x 6.5",

"Like mother, like daughter", white stoneware, lusters, 1998, 16" high x 8" x 6"