Editors of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

Copyright © 2002 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 48, No.2 - Summer 2002

Editors of this issue: Violeta Kelertas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 2002 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Elena Urbaitis, Works on Paper. With essays by Algimantas Patašius, Lolita Jablonskienė, and Elona Lubytė; translated from the original Lithuanian by Sigutė Jurkuvienė. Vilnius Academy of Arts Press, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2000. 240 pages. Price not specified. ISBN 9986-571-60-X.

The enduring relevance of a series of unique works spanning a full half-century of the artist's on-going career announces and asserts itself in these impressive full-color pages. The volume was assembled and first issued as a catalogue to document two separate exhibits under the same name that took place in Lithuania last year, the larger and more comprehensive of them at the Čiurlionis Art Museum in Kaunas. It has since acquired a distinction of its own by being designated one of the best designed Lithuanian books of the year. That it so extensively and judiciously reflects the work of a prominent Lithuanian artist who has been working primarily in the United States gives it a pronounced extraterritorial luster.

Lovely as the book is to look at, some credit for this surely must go to Alfonsas Žvilius and Mykolas Žvilius, who are on record for shaping its design and its layout, respectively. Particularly striking is a compact abundance that survives the abridgment of scale in each of the reproductions. The three introductory essays, translated into a sensible, reliable English, chart the background of the work from different yet complementary vantage points. The first of these, by Algimantas Patašius, plots the artist's progress from restless academic beginnings to a free development in the avant-garde. The second, by Lolita Jablonskienė, deftly and evocatively outlines the contextual tradition for nonobjective drawing. And the last one, by Elona Lubytė, assesses the cumulative effect of the drawings in light of contemporary trends.

Elena Urbaitis has pursued a working career over the last four decades as a painter and sculptor in New York. This was preceded by a protracted period of study, which began during wartime at an art school in her native Kaunas, was continued at the celebrated Akademie der Bildenden Kunste in Munich and on a postwar fellowship in Paris, and after her ultimate relocation to New York culminated in a fine arts degree from Columbia University. Simultaneously, the artist was evolving her output across the broad prevailing span in contemporary art and theoretical aesthetics.

On the basis of the assembled drawings, Urbaitis's line of development is firmly rooted in the Northern European naturalist tradition. The drawings and watercolors from the European years are all without exception studies of the human figure, from delicate portrait close-ups and hieratic character sketches to full-length studio anatomies. But already, as these works attest, with the artist's growing command of pencil-point and charcoal, brushes and tints, a thematic focus begins to emerge. Rather than being simply gestural or expressive, structural or static, the early academic studies begin to convey what for the artist would become, on the evidence of the last third of this book, the ultimate and predominant formal preoccupation, namely, to uncover and represent the multiplicity inherent in the dynamics of the human figure.

While a certain proclivity for patterning and, to some extent, textural disruption accompanies this last phase, the middle rangefrom her arrival in New York through to the early 1980sis a period of formal and thematic consolidation, when Urbaitis made her first mature works. New York City was especially generous to artists during the 50s and 60s, accommodating a profusion of styles from Abstract Expressionism to conceptual Minimalism. Within Pop Art alone, the multiform plethora is mind boggling. Urbaitis seems to have given each of these some consideration in turn and, with her blend of cautious absorption and empowered self-assurance, raided them gleefully to her advantage. Yet, while there are traditional European remnants throughout the 50s (in a whole series of watercolors from 1953-1954, for instance, that are outright Picasso), even more tentative forays brought in references from popular, nonvisual culture (several collages from the same period). Surrealist traces are playfully engaged to redeem clichés of transience in "Time Passage" from 1958. Two satirical, feminist etchings from 1960 depict the female at two extremes of imposed disadvantage: as a headless, armless nude classically recumbent in a setting of overt scintillation, "Underground," and as a full-grown, captive nude stunted and squat inside a uterine oval, "A Woman". There is, too, the stunning abstract singularity of "Blue Black" (1962), as emblematic in the scaled-down purity of its two colors as any of the far more grandiose "Spanish Elegies" by Robert Motherwell, if only for the bold, even intrusive, suggestion of space in its reduced state.

But by far the artist's most extensive and enduring investigations have focused on capturing multiple-physical realignments on the single plane of the drawing paper. There is already a strong hint of this in various early overlapping drawings, including the clear ambiguity of a seated "Figure" (1961), whose broad strokes may be seen to represent either one: a nondescript person with legs crossed and a small head pinched into anonymity, or the gaping profile of an oversized head propped precariously on a shrunken body. Later explorations, however, took a turn away from the exclusive delineation of a single subject and toward formal repetition, image duplication, and serial variation. One manifold permutation registers the same image in two monoprints: "Group" (1989) shows four standing nudes from the back, or a single nude in four slightly different postures, and "Star" (1993) has exactly the same arrangement, with the background chromatically reversed and an overlay of disparate elements, including four alphabetical characters.

A number of the more recent drawings are detailed preliminary studies for multipanel paintings and sculptures on a monumental scale. As time may be said to be a dense coalition of separate, intricate moments, the overall persistence of the figural subject is aligned intrinsically with movement. Urbaitis persuades us that the resulting image has less to do with an arrested or stop-action moment as with a rhythmic design that intimates and even invites repetition. As much as the abstraction may relate to or arise from a specific figure or pattern of figures, its actual depiction traces and already maintains the definitive outline it will come to resolve in.

Vyt. Bakaitis

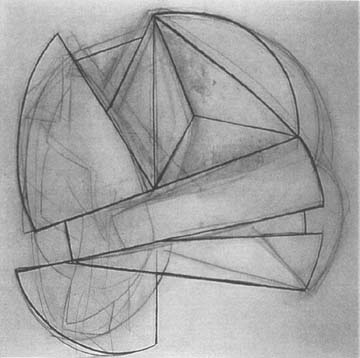

N709

1993, 53" x 51", charcoal on paper

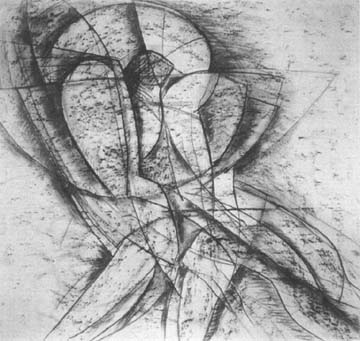

N 706

1993, 43"x 47", charcoal on paper

Sitting Male

1993, 12" x 9", pen and ink on paper

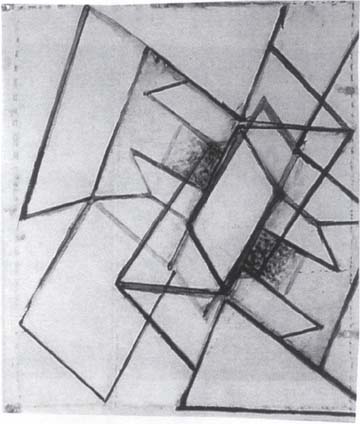

Untitled,

1992, 17"x 15", monoprint

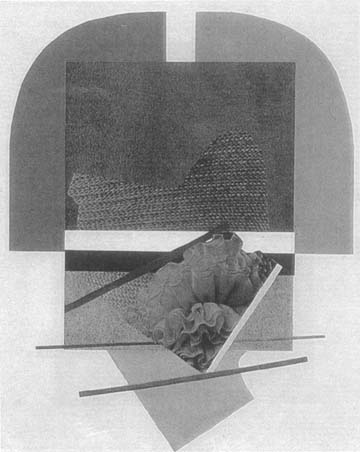

Fragile,

1974, 17.5"x 14", collage

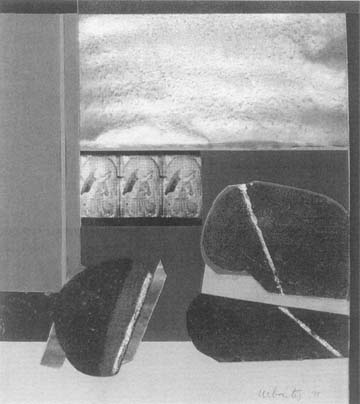

Digressed Angels,

1975, 19"x 11", collage

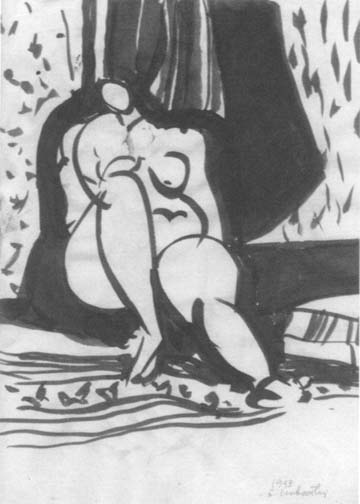

Sitting Nude III,

1993, 12"x 19", pen and ink on paper