Editor of this issue: Stasys Goštautas

Copyright © 2003 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 49, No.4 - Winter 2003

Editor of this issue: Stasys Goštautas ISSN 0024-5089 Copyright © 2003 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Note from the Editor

M.K. ČlURLIONIS, THE FAMOUS UNKNOWN

STASYS GOŠTAUTAS

I.

Until just before Lithuanian independence [1991] Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis's [1875-1911] works were for decades the best kept secret in the Kaunas Museum that bears his name. There are many reasons why a decade ago the Lithuanian artist's works suddenly started to travel abroad.

Čiurlionis's paintings, mostly tempera painted on cheap cardboard, were slowly fading. Something had to be done. Vytautas Landsbergis, just before he became the hero of the independence movement, visited us in Westwood, Massachusetts in February 1988, seeking advice and assistance. My wife, Maryte, suggested engaging Polaroid to produce high quality reproductions. The Polaroid Corporation expressed interest and approved the project, but the Lithuanian Foundation in Chicago had other priorities. Today, almost the same quality can be attained with digital techniques not then available, but with every passing day, the paintings are fading irretrievably. For years, the Čiurlionis Museum in Kaunas has been under the guidance of the best restaurateurs of the world so, if not completely halted, the fading of the works has been somewhat slowed.

With the death of Valerija Čiurlionytė Karužienė [1897-1982], the sister of the artist, who argued against Čiurlionis's paintings leaving the country, the Lithuanian artist's works started to travel abroad. She firmly believed that the only way to preserve the art of her brother was to keep his works sequestered in Kaunas, not letting them be shown in any other part of the world, and she managed to keep Čiurlionis's art a secret for over seventy years. The only exceptions were the special shows held in the Academy of Arts of the USSR [1954] and Tretiakov Gallery [1975], both in Moscow. But these were limited exhibits, and very few if any of the world's connoisseurs got a chance to see him. As it happened, in the train to Moscow, some of Čiurlionis's paintings did get damaged by rain, confirming Valerija's worst fears.

As yet another exception, Čiurlionis's works were shown in West Berlin in 1979, as a late centennial homage, in the Charlottenburg Castle, with limited success. Ironically, the most important Čiurlionis scholar at that time, Vytautas Landsbergis, did not get permission from the Soviet authorities to leave the country. After 1989, Čiurlionis was shown almost yearly in some art capital of the world. The only capital he has not yet been shown is in Vilnius, which is too close to Kaunas, but too remote for most world travelers.

A long forgotten project to exhibit Čiurlionis in Washington or New York has been abandoned, because some overly ambitious compatriots decided that nothing but the Metropolitan Museum meets their standard. If we had the same attitude toward Paris and waited to show him in the Louvre, I am sure we would be waiting still. We refuse in effect the possibility of having Čiurlionis's works exhibited in, for example, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, part of the Smithsonian, for the remote chance to show him in the Metropolitan.

My personal conviction is that, in spite of the risk to his work, Čiurlionis should be seen by as many people as possible in case nothing can be done to preserve his paintings for posterity. The danger of oblivion that was his destiny in Kaunas is greater than the risk of damage to his works in transit around the world. At the least we can expect some serious studies to come of it. I know that some five doctoral dissertations are being written or have already been written in Wisconsin, Florida, London and Paris. I have not yet seen the texts, but they are more than was done in fifty years of Lithuanian exile, when no one wished to write without viewing the originals. The only exception was the unpublished thesis of Mindaugas Nasvytis ["The Work of Čiurlionis in Relation to his Period," 1972]. In Lithuania, a splendid doctoral dissertation has finally been written, long overdue after the attempt of Jonas Umbrazas (1967) to be independent from Soviet art propaganda, by Rasutė Andriušytė Žukienė ["M.K. Čiurlionis: between Symbolism and Modernism," 2000], which is yet to be published. However, the few chapters that have appeared here and there show that she has an independent mind and Landsbergis is not alone.

Curiously, there are two Lithuanian world-class and yet largely unknown artists. They could not be more dissimilar in time, approach and technique. Čiurlionis, who barely had time to complete some 300 paintings before his premature death in 1911, and Jurgis [George] Maciunas [1931-1978], who aimed to be an anti-artist and loved to play and shock his neighbors through his Fluxus movement [1963], a holdover from Dada and Pop and Happenings and anything minimal or outrageous, but who never expected to have his outbursts displayed in art museums. However, he gathered a creative group of artists, or anti-artists, around the world who were mutually inspired.

When, Čiurlionis's works were exhibited at the d'Orsay museum, in Paris in 2000-2001, more people saw them in three days than in Kaunas over a year. The same thing happened in Warsaw and Barcelona and Madrid. Now, having seen the originals, the art historians could evaluate the painter without having to interpret poorly made Soviet reproductions. Robert Rosenblum, in Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition [New York, Harper and Row, 1975, p. 71], wrote quite a sensible paragraph, but confessed to me that he had never seen Čiurlionis's originals. I don't know if any monographs appeared in response to these exhibits, but the catalogueswith few exceptionswere impressive; and the press everywhere gave him an outstanding ovation, as a major discovery of an important painter.

The Paris show especially, occurring simultaneously with the Art Nouveau exhibit in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, previously in London, put him in the context of world art in 1900, or the fin-de-siècle. Čiurlionis was part of the same brilliant generation that produced Gauguin, Van Gogh, Munch, Klimt, and of course, Kandinsky, Jawlensky, Kupka, Gaudi, Tiffany, Galle, and hundreds of other artists that we venerate so highly. [For more about this period in Munich, see the article by Laima Laučkaitė in this issue.]

Čiurlionis has been claimed by or interpreted as being part of every movement since the end of the nineteenth century, starting with the Pre-Raphaelites through Symbolism and Art Nouveau to Surrealism and Abstraction and in a way, he fits everywhere and yet nowhere. It is surprising for such a modest man of modest education and a rather limited knowledge of the art of painting.

As was the case with Cézanne, Proust, Mallarmé, the brothers Goncourt, and many of his contemporaries, most of his thoughts and dreams were put on paper in letters to his family and friends. The precious Polish correspondence of Čiurlionis, published in less-than-accurate Lithuanian translation in 1960, is being translated again and will be published in a bilingual edition soon. During the Leipzig period alone he wrote over one hundred letters to his brother Povilas and to his good friend in Warsaw Eugeniusz Morawski. There are so many questions we hope to answer through the new translation of his correspondence. By the way, Povilas Čiurlionis [1884-1945], a gifted musician and architect, like so many emigrants from the Tsarist empire, was a draft dodger, who worked for a while in the mills of Lawrence, Massachusetts, and played organ in the local Lithuanian church. In 1904, he was admitted to the School of Architecture at Columbia University.

For Čiurlionis it all began in the middle of 1901, when he decided to further his musical knowledge in a Master's program at Leipzig university, then a school famous for the arts. It was there that he decided to pursue his real love, painting, but without abandoning music, which supported him for the rest of his life. He worked as a music teacher and performer, but devoted most of his time to the fantasy of painting. There was a beautiful art museum that he frequented in Leipzig and there he came to admire the Symbolists. One year later he wrote to his brother Povilas on a postcard reproduction of Arnold Bocklin's Prometheus, boasting: "I have already painted one symbolistic painting." It could have been Composition [1903, pastel on paper], one of many so entitled, but the fact that he started as a Symbolist, already implies that he was part of the 1900 period. By the way, Bocklin, mentioned and admired by Čiurlionis, was a favorite of the Vienna Secession, one more link of the artist to the fin-de-siècle.

Čiurlionis would steal from his meager scholarship stipend for food, to buy paper and paint, and would justify this act by writing that man sometimes needs entertainment, and his was the brush. This need probably came thanks to his love of nature"I have a passionate desire to study nature" he wrote to his brother Povilas. Many artists of the time, weary of positivism and naturalism, turned to nature for inspiration and relief. Čiurlionis could not wait two years to complete the master's program and did it in one year and, as if escaping from prison, left abruptly for the city of his birth, Druskininkai. He soon enrolled in J. Kauzik's drawing studio in Warsaw and in the academy of Fine Arts as soon as it opened its doors [March 15, 1904]. Finally in school, at the age of 27, he was the happiest man in town, with his pencil and brushes working day and night, as if possessed.

One of his first series was called Let it Be or the Creation of the World, [1905], a beautiful world of nature inspired by his homeland, but also different, created by man. Again, in a letter to his brother, Povilas, he explains:

The last cycle Let it Be is unfinished; I think I will paint it all my life, depending, of course, on how many new ideas I get. It is the creation of the world, not our world, as in the Bible, but the creation of another fantastic world... [April 20, 1905]

Symbolism led Čiurlionis to Art Nouveauthe first global art movement. It is hard to say where it started, but almost immediately all around the world [Europe, the Americas, Japan] it produced robust samples of beautiful works designed for people to enjoy in their homes prior to being hung on museum walls. Čiurlionis found inspiration in the Young Poland (Mloda Polska) movement [see Radoslaw Okulicz-Kozaryn's illuminating paper in this issue] and of course the Vienna Secession, German Jugendstil, Italian Stile floreale, Belgian Le Style des Vingt, Catalan Modernismo, Russian Mir Isskusstvo ["World of Art"], and Neue Künstler-vereinigung München (The New Association of Munich Artists), which among many artists invited Robert Delaunay and Čiurlionis to the Second Exhibition of the Society in June 1910. One year later, the association evolved into Blaue Reiter. Art Nouveau came to Lithuania through Warsaw, St. Petersburg and Riga, especially the latter, where Mikhail Eisenstein [1867-1921, the father of film director Sergei Eisenstein,] an architect, embellished the city with Art Nouveau buildings. But for Čiurlionis all this was a little too late.

In Lithuania, Art Nouveau was mostly a poetic and patriotic movement, as envisioned in the romantic figure of Maironis, who wrote a book called Jaunoji Lietuva [Young Lithuania] in answer to the Mloda Polska, and was like a prelude to the Lithuanian independence of 1918. Čiurlionis was happy designing books, prints, and posters in the new style. He probably was the only figure representing Art Nouveau in Lithuania and was for a while misunderstood. Even now, people in Lithuania question his talent but like him, because he is Lithuanian and fantastic.

I do not agree with Akira Moriguchi, Assistant Director of the Sezon Museum of Art, that Čiurlionis did not paint in the fin-de-siècle mood. On the contrary, he was of that period and part of that very original generation.

It is not the purpose of this note to write a history of Art Nouveau but to

place Čiur

lionis among his contemporaries. The following list of exhibitions provides

further proof of how deeply involved the Lithuanian artist was with his

contemporaries. The latest exhibit in Madrid opened on November 5, 2003. It goes

deeply into the polemic that began fifty years ago, between Kandinsky and

Čiurlionis, for the primacy of abstraction. Perhaps this exhibition will help to

resolve the matter.

This is a copy of the communication inviting participation in the Catalogue of

the Second exhibition

of the Society "Neue Künstlervereinigung

München," dated June 1910, in German,

that

according to Mrs. Čiurlionis arrived late. An identical invitation was sent to

the artist in French.

II.

M.K. ČIURLIONIS EXHIBITS ABROAD

1. Duisburg 1989Čiurlionis und die litauische Malerei: 1900-1940.

Wilhelm-Lehmbruck-Museum.

Catalogue: Čiurlionis und die litauische Malerei:

1900-1940. Duisburg, Wilhelm-Lehmbruck-Museum, 1989. There were seventeen works

by Čiur

lionis.

2/3. Berlin, Bruxelles 1991Zum Raum wird hier die

Zeit: Die Symbolisten und Richard Wagner Akademie der Kiinste zu Berlin/De la

musique avant toute chose: Les Symbolistes Richard Wagner. Bruxelles, Maison du

spectacleLa Bellone.

Catalogue: Les Symbolistes Richard Wagner. Die Symbolisten

und Richard Wagner. Berlin, Edition Hentrich 1991. Five Čiurlionis works in the

exhibit.

4. Bonn 1992Territorium artis- Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle

der Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

Catalogue:Territorium artis. Bonn, Verlag

Gerd Hatje, 1992. Fourteen Čiurlionis works on display.

5. Tokyo1992Čiurlionis: Fantasist and Mystic of Fin-de-siecle

Lithuania. Tokyo, Sezon Museum of Art.

Catalogue: Čiurlionis: Fantasist and

Mystic of Fin-de-Siecle Lithuania. Tokyo, Sezon Museum of Art, 1992. The only

exhibit of the Lithuanian artist in the Far East. Sixty of his works on display.

Japan is the only country that formed a society,"Friends of Čiurlionis,"

before they had even seen his originals.

6. Bonn 1994Europa, Europa: Das Jahrhundert der Avantgarde in Mittel-

und Osteuropa, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

Catalogue: Europa, Europa: Das Jahrhundert der Avantgarde in Mittel- und

Osteuropa. The Century of the Avantgarde in Central and Eastern Europe. Bonn, Kunst- und Ausstelungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1994. Ten Čiurlionis

works on display.

7. Frankfurt am Main 1995Okkultism und Avantgarde:

von Munch bis Mondrian, 1900-1915.

Catalogue: Okkultism und Avantgarde: von

Munch bis Mondrian, 1900-1915. Occultism and Avantgarde: from Munch to Mondrian,

1900-1915. Frankfurt, Schirn Kunsthalle, 1995. With thirty works by the artist.

8. Koln 1998Die Welt als grosse Sinfonie. Mikalojus Konstan-tinas

Čiurlionis (1875-1911). Wallraf-Richartz-Museum.

Catalogue: Die Welt als grosse

Sinfonie. Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis (1875-1911). Koln, Oktagon-Verlag,

1998. Ninety-six Čiurlionis works on display.

9. Montreal 1999Cosmos.

From Romanticism to the Avant-garde. The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Jean Noel

Desmarais Pavilion.

Catalogue: Cosmos. From Romanticism to the Avant-garde.

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Prestel Verlag, 1999; Du Romantisme a

I'Avantgarde. Musee des Beaux-Arts de Montreal, Gallimard, 1999. The only

exhibit of Čiurlionis's works in North America. Only three samples of his work

on display.

10. Barcelona 1999/2000Cosmos. Del romanticismo a la

van-guardia 1801-2001. Barcelona, Centre de Cultura Contempo-rania de Barcelona.

Catalogue: Cosmos. Del romanticismo a la vanguardia 1801-2001. Centre de Cultura

Contemporania de Barcelona, Institut d'Edicions, 1999.

11/12. Madrid

1999/2000Barcelona 2000El Simbolismo ruso, Sala de Exposiciones de la

Fundacion "la Caixa." Barcelona, Centra Cultural de la Fundacion "la Caixa."

Catalogue: El Simbolismo ruso. Fundacion "la Caixa," 1999. Three works of the

artist on display.

13. Bordeaux 2000Le Symbolisme russe. Musee des

Beaux Arts de Bordeaux.

Catalogue: Le Symbolisme russe. Musee des Beaux Arts

de Bordeaux, 2000.

14. Nantes 2000Vision Machine. Musee des Beaux Arts de Nantes.

Catalogue: Vision Machine. Paris, Somogy editions d'art, 2000. Seventeen

Čiurlionis works on display.

15. Venice 2000Cosmos. From Goya to de

Chirico, from Friedrich to Kiefer. Art in Pursuit of the Infinite, Venice,

Palazzo Grassi.

Catalogue: Cosmos. From Goya to de Chirico, from Friedrich to

Kiefer. Art in Pursuit of the Infinite. Bompiani, 2000. Five works by the artist

in the exhibit.

16. Paris 2000/2001M.K. Čiurlionis (1875-1911), Musee

d'Orsay.

Catalogue: M. K. Čiurlionis (1875-1911). Paris, Editions de la

Reunion des musees nationaux, 2000. The most significant exhibit of Čiurlionis'

works abroad with ninety-seven on display.

17. Grenoble 2001M.K. Čiurlionis (1875-1911), Musee de Grenoble [same

content as above].

18. Bellinzona 2001Figurazioni Ideali. M.K.

Čiurlionis. Alberto Martini. Albert Trachsel. Museo Villa dei Cedri.

Catalogue: Figurazioni Ideali. M. K. Čiurlionis. Alberto Martini. Albert

Trachsel. Bellinzona, Museo Villa dei Cedri, 2001. Thirty-nine Čiurlionis works

in the exhibition.

19. Warsaw/Poznan 2001M.K. Čiurlionis (1875-1911)

Twor-czosc, osobowosc, srodowisko. Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie.

Catalogue:

M.K. Čiurlionis. Tworczosc, osobozuos'c, srodowisko. Nacionalinis M.K.

Čiurlionio dailes muziejus, 2001. First exhibit of his works since his death. A

total of 134 works are shown. Exhibits of 115 works in Poznari: October 21,

2001-November 28, 2001.

20. Madrid 2003Musical Analogies. Kandinsky and His Contemporaries,

Museum Thyssen-Bornemisza.

Catalogue: Analogias Musicales. Kandinsky y sus

Contemporaneos. Madrid, Fundacion Colleccion Thyssen-Bornemisza, 2003. Nineteen

Čiur

lionis's works on display.

21. Paris 2003At the Origins of Abstraction 1800-1914. D'Orsay, Twelve

works on display, November 5, 2003February 22, 2004.

Since Čiurlionis and

abstraction have always been a point of controversy, for the record, here are

the twelve works included in this exhibit:

Fugue. From the diptych "Prelude. Fugue," 1908.

Sonata No. 5 (Sonata of the Sea,) Allegro, Andante, Finale, 1908.

Lithuanian Graveyard, 1909.

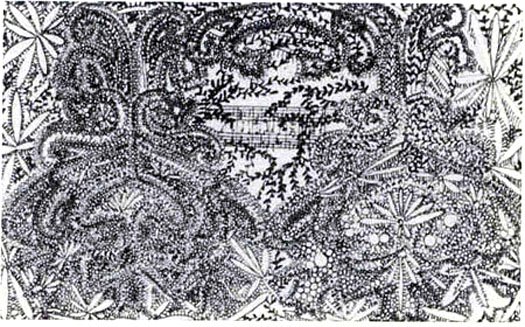

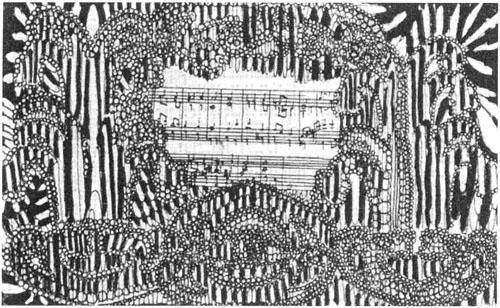

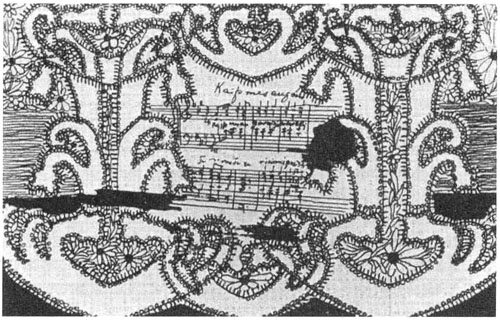

Vignette for the folk song "The dark night will fall," 1909.

Vignette for the folk song "Saturday night party," 1909.

Vignette for the folk song "The dark night will fall" [second version],1909.

Vignette for the folk song "When we were growing up," 1909.

Vignette for the folk song "On Yonder side of the Nemunas," 1909.

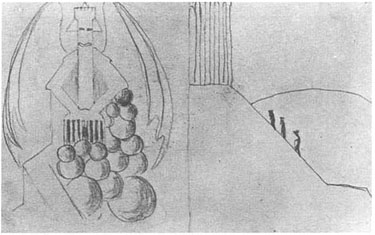

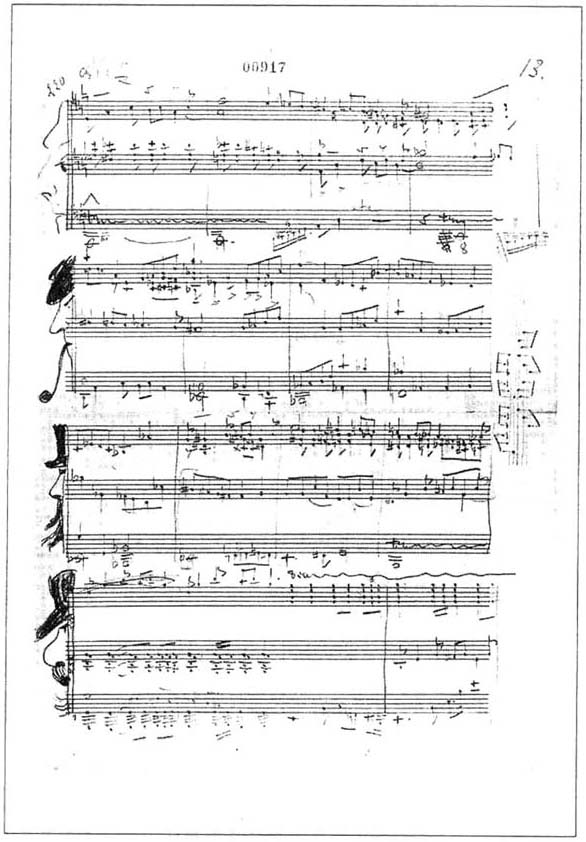

Sketch for the diptych "Prelude. Fugue" in the sketch book, 1907.

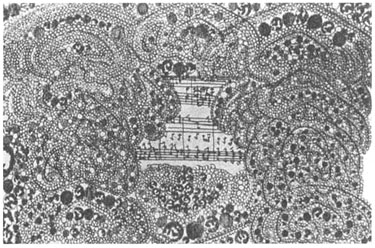

Transcription of the symphonic poem "The Sea" for the piano, 1903.

Sketch from the diptych "Prelude. Fugue," 1908.

Vignette for the folk song "On Yonder side of the Nemunas," 1909.

Vignette for the folk song "The dark night

will fall," 1909.

Vignette for the folk song "The dark night will fall" [second version],1909.

Vignette for the folk song "Saturday night party," 1909.

Vignette for the folk song "When we were growing up," 1909.

Transcription of the symphony poem "The Sea" for piano,

India ink on paper, 10x19.5cm.

EpilogueFor organizing these twenty-one exhibits around the globe, credit goes to Osvaldas Daugelis, the director of the Museum; Nijole Adomavičienė, the curator of the collection; and the dedicated staff, members like Birutė Federavičienė, the person most responsible for the catalogue raisonne of M.K. Cturlionis; Milda Kulikauskienė, the ex curator and responsible for the Japanese exhibit; and Vaiva Kavaliauskaite Laukaitiene, who is always ready and willing to help.

Also, each issue of Lituanus would be impossible without a team of translators, who humbly do the impossible task rendering the text from different languages into English. My sincere thanks to Prof. Aušra Kubilius from Southern New Hampshire University and Magdalena Zapędowska from Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan.

Finally, this is the fifth issue in which Lituanus features the Lithuanian painter and composer. If we analyze the first issues, we find that most of the contributors were Lithuanian émigrés. Recently, most of them are foreigners or natives from Lithuania. We also, humbly claim that Lituanus is the only academic journal that has devoted so many issues to M.K. Čiurlionis over the past fifty years [1954-2004] .

The titles and the English translation of Čiurlionis's works in this issue are taken from M.K. ČiurlionisPainter and Composer. Collected Essays and Notes, 1906-1989. Vilnius: Vaga, 1994.

Stasys Goštautas, Guest Editor