Editor of this issue: Stasys Goštautas

Copyright © 2003 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 49, No.4 - Winter 2003

Editor of this issue: Stasys Goštautas ISSN 0024-5089 Copyright © 2003 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

M. K. ČIURLIONIS AND MARIANNE

VON WEREFKIN:

THEIR PATHS AND WATERSHEDS

LAIMA LAUČKAITĖ

Institute of Culture, Philosophy and Art, Vilnius

At the start of the twentieth century, the modern art world was marked by close international ties among the artists of Paris, St. Petersburg, Munich, Berlin, and Moscow. The work of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, however, became available to avant-garde artists of the time only after 1911: at large posthumous exhibitions in Moscow (1911/ 1912), and St. Petersburg and at a post-impressionist show in London (1912), where a few of his paintings were displayed. He must have been known earlier, however, because in 1910 he was invited to participate in an exhibition of the German avant-garde group Neue Künstlervereinigung München (The New Artists Association of Munich).1 Although the invitation came late2 and Čiurlionis's works were not sent to this show, the very fact of the invitation deserves attention. It indicates that his work had to be known not only to Lithuanian, Russian, and Polish avant-garde artists but also to the Germans. This invitationa mysterious and little-examined moment in Čiurlionis's biographyraises the following question: Who of the New Artists Association of Munich could have known Čiurlionis's work and suggested inviting him to this group's exhibition?

Formed in 1909 in Munich, the association was made up of young artists resolved to search for new paths in art. A distinct feature of the group was its internationalism. The initiators were the Russian artists Wassily Kandinsky, Alexej von Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin, and Gabriele Münter. Members included the German artists Alexander Kanoldt and Adolf Erbslöh and the Austrian Alfred Kubin. The Russians Wladimir von Bechtejeff, Alexander Sacharoff, and Moissey Kogan and the Italian Erma Bossi immediately joined the group. The French artists Pierre Girieud and Henri le Fauçonnier joined in 1910, The German painter Franz Marc in 1911; and the Russian Alexander Mogilevsky in 1912. This international group collaborated with the artistic avant-garde of Paris, St. Petersburg, and Moscow. The association mounted several exhibitions in Munich. In 1909 only the group's members participated. In 1910/1911 they invited French, Russian, and artists of other nationalitiesVladimir Burliuk, Georges Braque, Andre Derain, Kees van Dongen, Pablo Picasso, Maurice de Vlaminck; these also participated in the 1911/1912 show. The exhibitions were not uniform stylistically, containing clear examples of Fauvism, primitivism, synthétisme, and cubism. Although the association did not survive for long, its significance for the history of modern art is indicated by the fact that when this group dissolved in 1911 some of its members founded the noted German expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider).

Čiurlionis was among the invitees to the second, the most significant and extensive, exhibition of 1910/1911. Who of the association's members could have seen his works? The invitation, it seems, was signed by Kandinsky, the leader of the group; thus the first thought is that he recommended Čiurlionis.3 Moreover, in 1949 art historian Aleksis Rannit raised the hypothesis that Kandinsky knew the work of Čiurlionis and that the latter deserves the title of the founder of abstract art. However, Nina Kandinsky and art critic Will Grohmann, a specialist in Kandinsky's work, asserted that Kandinsky had not seen Čiurlionis's art before creating his own first nonfigurative works. The dispute arose over the following fateful question: Who deserves the name of the founder of abstract art, Kandinsky or Čiurlionis? Both sides wanted to win this debate unconditionally. Kandinsky could not have seen Čiurlionis's abstract works because the cycles of the Lithuanian artist that show signs of abstractionism were exhibited only in Vilnius and Kaunas. Creation of the World was displayed at the first Lithuanian Art Exhibition in 1908, while Winter Cycle was shown at the Second Lithuanian Art Exhibition in 1909. Perhaps Kandinsky could have seen Čiurlionis's paintings in Russia in 1910? This hypothesis must also be rejected because Čiurlionis's works were shown in the Seventh Exhibition of the Sojuz russkich chudoznikov (Union of Russian Artists) in Moscow at the end of 1909/beginning of 1910 and in St. Petersburg during February and March of 1910, but Kandinsky only visited Moscow in October and St. Petersburg in November of 1910. Thus the two artists missed each other.4

Among the members of the Munich Association there was, however, another artist who maintained close ties not only with Russia but also with Lithuania: Marianne von Werefkin (in Lithuanian, Mariana Veriovkina). The paths of her life and work often paralleled those of Čiurlionissometimes they passed each other, sometimes they diverged, sometimes they converged. Jelena Hahl-Koch, a noted Kandinsky expert and curator of the Lenbachhaus Gallery in Munich, was the first to hypothesize that von Werefkin was the only member of The New Association of Munich Artists to have seen Čiurlionis's work.5

|

|

|

Marianne von Werefkin (1860-1938), a painter of Russian extraction, spent her youth in Lithuania because her father had an estate not far from Utena. She studied at Moscow's School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture and took private lessons with the painter Ilya Repin in St. Petersburg. Her early paintings-realistic portraits characterized by pictoriality and sketchy strokeswere exhibited in peredvizhniki shows ("Wanderers movement," so called because of their traveling exhibits). In 1896, together with the Russian painter Alexej von Jawlensky, von Werefkin went to Munich to further her studies and lived there until World War I. Energetic, intellectual, and talented, she quickly became involved in Munich's avant-garde movement. She created her own salon, which was frequented by artists, musicians, writers, politicians, Munich's bohemians and aristocrats. She "knew everyone and everything" in the art world. Continually visited by Russia's artists and other cultural figures, her home became an unusual cultural "embassy" in Munich.

Sometimes von Werefkin would return to Lithuania, which she considered her homeland. Having studied material yet unknown to Western art criticism (her abundant epistolary legacy housed in the manuscript section of the Lithuanian National Martynas Mažvydas Library), I can affirm that she really did visit Lithuania several times in the early part of the twentieth century, i.e., during 1909/1910 and in 1914.

In late 1909/early 1910 Marianne von Werefkin, because of a leg ailment, had a lengthy stay in Kaunas with her brother Peter von Werefkin, who was then governor of Kaunas. This visit is described in detail in her letters to her artist friend von Jawlensky in Munich. She describes her daily activities, events, visits, acquaintances, reflections on art, and so on. Čiurlionis is not mentioned in these letters. At the time, she would have been unable to see his work in Kaunas or even run into him since Čiurlionis was already ill and being treated in St. Petersburg and Druskininkai. She must have heard of him, however, and seen the Lithuanian Art Society's notecard reproductions of his work.

In 1908, the Second Lithuanian Art Exhibition was transferred from Vilnius to Kaunas; it included a large collec-tion of Čiurlionis's works. This show was not an ordinary event in the artistic life of Kaunas at the beginning of the twentieth century and enjoyed a great success with the public. During the opening ceremonies Peter von Werefkin gave an enthusiastic welcoming speech. A cultured, well-read man, Peter was the closest family member to Marianne. According to her letters, during her Kaunas visit, she spent long evenings with him discussing life, creative work, people.

Evenings Peter and I both stay up late into the night. And in front of our minds' eyes parade all the negative aspects of this life, all that debases it and converts events and people into nightmares. But in the morningagain the miracles of the visible world. These days spent together with Peter gave much to my soulall only good. And they gave much to my consciousnessall only bad. Sorrow becoming a physical pain, sorrow for all that is good which is disappearing in Russiathat was the result.6

Marianne painfully experienced the triviality of narrow-minded provincial life and interests:

Job and family concernsthe firm foundation, a bonus and promotionpleasant fantasies, scandalsdaily bread, and their joys remind one of those "common folk" sweets that you wouldn't dare put in your mouth. I think about Munich like about health. Here everything is torment, that aversion to beauty and that horrible existence and that solemn literature and the complete needlessness of art.7

Marianne's brother could not have failed to tell her about the rare exceptions in the indigenous life therethe higher manifestations of spiritual life, the art exhibition in Kaunas, and the artist-visionary Čiurlionis is attested by the fact that in 1911 he wanted to acquire Čiurlionis's painting Silence (1907).8

Marianne stayed in Kaunas from December 1909; she returned to Munich only after Easter in 1910. Could it be a coincidence that right after her return from Lithuania Čiurlionis became known to The New Artists Association of Munich and was sent an invitation to participate in this group's second exhibition?

While visiting Vilnius in the spring of 1914, Marianne saw a comprehensive posthumous exhibition of Čiurlionis's works.9 At that time her temperas were being shown in the Seventh Exhibition of the Vilnius Art Association10. (Čiurlionis had belonged to this association; he had been one of its founders and his works had been exhibited in the group's first show in 1909.)11

It is elucidative to examine the aesthetic views of the two artiststo compare Čiurlionis's thoughts as expressed in his letters, articles, and diaries with von Werefkin's lecture on art given in Vilnius in 1914.12 Their understanding of the artist's role is similar, since both describe art as the highest divine sphere and the artist as the one chosen, the one called to serve and evangelize art. "Our entire life will burn on the altar of Eternal, Infinite, Omnipotent Art"13 Čiurlionis wrote to his wife, the writer Sofija Kymantaitė, in 1908. He perceived the meaning of life as a sacrifice to art, which he characterized with adjectives selected from the religious lexicon describing God. In her lecture von Werefkin presents a short analogous formula: "ArtGod; the artistits prophet. They understand each other. But how to reveal God to people, how to make the intangible intelligible through the help of symbols that are not understood by everyone?"14

The sources of this conception of art lie in the aesthetic of Romanticism, which was reborn in the views of neo-Romanticism and Symbolism at the end of the nineteenth century. Čiurlionis and von Werefkin are also bound to Romanticism through the exaltation of emotions, primarily love, because without love art is merely a lifeless, learned, mechanical craft: "Any art is a concentrated feeling of love elevated to a world view and translated into an artistic language of symbols",15 states von Werefkin. That same love motif is repeated in Čiurlionis's texts: "It [national art] is the first expression of love and love of art, the first manifestation of spiritual matters, the first expression of creation."16

For Čiurlionis as for von Werefkin the world is split in tworeality with its daily routine, its banality, its insignificant provincial-life concerns and a spiritual transcendent reality, which art is called upon to reveal. For this reason in Čiurlionis's work the fantasy rather than the real world appears; there are almost no scenes inspired by nature or reality. The artist is not interested in tangible, physical matter. In a similar way, von Werefkin describes her artistic credo in her diary-like Letters to a Stranger (1902):

I love what doesn't exist. I love love that doesn't exist, which extends above you like an invisible city, like uncapturable smoke, a love that evokes a longing for enchanted lands, which fills the head with magical scenes, which confers strength and grandeur, which leads all beings to perfection, which adorns you in marvelous clothes, which increases painting abilities, which crowns you king of all goals, which makes you a god of creation.17

In art she is interested in what does not exist in realitythe intangible, the invisible, the inaudible. She extols this spiritual world of creativity as perfect, wonderful, miraculous, powerful, divine. Describing her art she conforms to the biblical phrase "My kingdom is not of this world." Rejecting the principles of positivism and the images of realism and naturalism, all symbolist painters could affirm this statement.

The similarities between Čiurlionis's and von Werefkin's views are not accidental. Both artists belonged to the generation that matured under the influence of the ideas of Symbolism. Living in St. Petersburg, von Werefkin knew Russian symbolist literature well; she associated with the writers Leonid Andrejev, Konstantin Balmont, and Dmitri Merezhkov and was close to Sergei Diaghilev, the publisher of the journal Mir iskusstvo (World of Art).18 She also associated with painters of the World of Art group, Leon Bakst, Osip Braz, and Mstislav Dobuzinski19 and was friends with the painter Viktor Borisov-Musatov, leader of the Russian symbolist group Golubaja rosa (The Blue Rose). Čiurlionis developed in an environment influenced by Warsaw, where symbolist views also predominated. At the Warsaw School of Fine Arts he studied under Kazimier Stabrowski, Ferdynand Ruszczyca, and Konrad Krzyzhanowski, all graduates of the St. Petersburg Fine Arts Academy and erstwhile members of the World of Art circle. Thus when Čiurlionis appeared on the St. Petersburg art scene, he was accepted as a compatriot; his works were exhibited at the World of Art and the Union of Russian Artists group shows. Both Čiurlionis and von Werefkin were interested in and read widely the works of theosophy, philosophy, psychology, cosmogony, and astronomy that were popular at the time. They were also connected through music. Čiurlionis was a professional composer; von Werefkin understood music well, followed news of the music world, and knew the work of Arnold Schonberg. Both painters admired Richard Wagner, the leading figure in Romantic music and a proponent of the synthesis of the arts.

Čiurlionis's work is symbolist, while von Werefkin's shows a distinct movement from Symbolism to Expres-sion-ism. It is known that when she arrived in Munich she did not paint at all for a while and began again only around 1906. The drawings done after her creative hiatus, for example, The Rocks and The Wave, in their composition and symbolism greatly resemble Čiurlionis's work and seem influenced by it. Their artistic styles soon begin to differ, however. Von Werefkin admired the new French style of painting, especially the combinations of pure striking colors, which she used in her own work and propagated among Munich's artistsfor which she was nicknamed "the Frenchwoman." As opposed to von Werefkin, Čiurlionis thought little of the French style. "The French painters produce the least novel things even though they push themselves forward and rush about the most,"20 he said in 1906 after viewing an exhibition of French painters during a visit to Munich. He used the shaded narrow range of colors valued at the end of the nineteenth centurybrownish yellows, greys, and greens.

In von Werefkin's work concrete motifs are transformed into painful and extreme expressionistic scenes because she uses a simplified rhythmic composition, primitive drawing, and bright striking colors. Čiurlionis's work is much more nuanced and subtle: fantastical fairy-tale motifs predominate, object forms seem to emerge through a mist, a complex musical rhythm shapes the composition, manifold perspectives appear. Both artists, however, are concerned with rendering not the visible but the inner spiritual world. The prevailing opinion in art criticism is that Symbolism and Expressionism have completely different artistic goals. But, as we see, von Werefkin's Expressionism, and Kandinsky's Abstractionism, inherit from Symbolism the conviction that art is an expression not of the real world but of a higher spiritual one. In this sense, the work of von Werefkin and of Kandinsky is related to that of Čiurlionis, although their artistic styles differ.

In the work of von Werefkin and Čiurlionis, iconographic motifs often coincide, expressing the Romantic tradition: a procession of travelers symbolizing the journey of life in the Funeral Symphony by Čiurlionis and the rhythmic line of figures liked by von Werefkinprocessions of women lugging bundles or heading to church (Return Home, 1909; The Path of the Cross, 1921). In both artists' work we find the motifs of a storm-battered sailboat and a lone tree in the mountains. We also find the Lithuanian variant of the cross in the countryside liked by the Romanticsa roofed, wayside shrine. Both artists knew this feature of the Lithuanian landscape well, but they interpreted it differently. In Čiurlionis's paintings a group of roofed posts becomes a harmonious cemetery landscape redolent of evening peace (Lithuanian Cemetery, 1909; Samogitian Cemetery, 1909). In her painting Early Spring (1907) beside a roofed post von Werefkin includes the figure of a tired man wearing a skull masksharply and expressionistically touching on the theme of death.

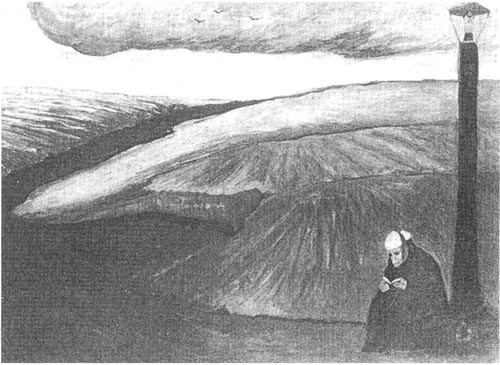

Marianne von Werefkin, "Early Spring", oil and tempera on

board, 55.2x73cm, 1907

The works of both artists show a liking for the motif of mountains, the embodiment of grandeur and eternity. In von Werefkin's later works mystical and religious sentiments intensify; her symbolic paintings convey the human states of loneliness, suffering, passion, and reconciliation with mortality. Her paintings from around 1917 to 1919 focus on dark, nocturnal mountain landscapes illuminated by an unearthly light; the works are full of apprehension, tension, trembling, the secret of supernatural forces (Holy Fire, 1919). In the 1920s, her temperas contrast huge mountains with a lonely, old, small person, suggesting the dichotomies of eternity and temporality, death and life, nature and humanity (The Evening of Life, 1922; One's Back Turned to Life, 1928). In her painting Via eterna an intoxicating, static, dark panorama of mountains is revealed; also, in a gorge a path of white snow guides a shepherd and his flockand in the same color as the snow a tiny church shines, like hope, on a mountaintop. With its visionary mood and its sensation of vast space and eternity, this work is close to those of Čiurlionis. Both artists are products of the fin-de-siècle epoch with its world-weary views, goals, and belief that "beyond this life there is another, one that attracts me more, mysterious, eternal"21a life both artists sought to reveal in their art.

Translated by Aušra Kubilius

Southern New Hampshire University

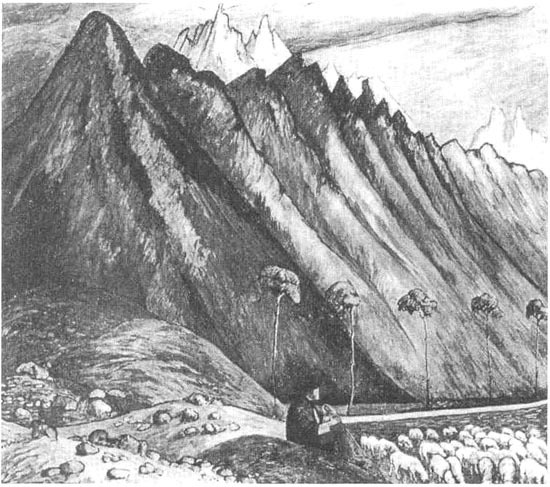

Marianne von Werefkin, "Evening of Life", tempera on cardboard,

67.5x72cm. 1922

1 We know about this invitation from a letter by Mrs. Sofija Čiurlionis to

M. Dobuzhinsky written on October 18, 1910. See M. K. Čiurlionis. Laiškai

Sofijai, Vilnius, 1973, p. 163.

2 It is not clear why Mrs. Čiurlionis in the above mentioned letter

complains that the invitation arrived too late, when the exhibit started in late

December. Ibid. (From the photostat copy published in this issue, it can

be seen that the invitation left in June and the reply had to arrive by August.

Editor's Note.)

3 Their paths crossed for the first time in 1904, when Čiurlionis was

a student at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, and Kandinsky in October of the

same year had an exhibition in the Salon of Krywult, Warsaw. See Polskie

zycie artystyczne w latach 1890-1918, Wroclaw-Warszawa-Krakow, 1967, p. 73.

4 Jelena Hahl-Koch. Kandinsky. Stuttgart, 1993, p. 134. For

documents on this subject, see M. K. Čiurlionis-Painter and Composer.

Collected Essays and Notes, 1906-1989. Vilnius: Vaga, 1994, pp. 210-231.

5 Jelena Hahl-Koch. "Mariannne Wcrcfkins russisches Erbe."

Marianne Werefkin. Gemälde und Skizzen. 28 09 80-23 11 80, Museum Wiesbaden,

p. 35.

6 Marianne Werefkin. "Life in Art. From the letters of Marianne

Werefkin to Alexej Jawlensky." Vilnius (in Russian), 1992, No. 3, p. 134.

7 Ibid., p. 128.

8 Lithuanian National Library of Martynas Mažvydas,

manuscript department, section 19, number 825,1.1.

9 A continuous Čiurlionis exhibition was held in Vilnius from October

1913 to November 1914, with minor interruptions.

10 Art Society of Vilnius 1908-1915 (Vilniaus dailės draugija)

Catalogue of the Exhibition. Vilnius, 1999, p. 8.

11 Ibid., p. 7.

12 Werefkin gave a lecture during a regular Art Society meeting, held

Saturdays, on March 22, 1914. The manuscript of the lecture is at the Marianne

Werefkin Foundation in the Comunale Museum of Ascona, without an invoice number.

13 M. K. Čiurlionis apie muziką ir dailę. Vilnius, 1960, p.

238.

14 Op. cit. As noted Werefkin gave a lecture during a regular

Art Society meeting, held Saturdays, on March 22,1914.12 ,1.20.

15 Ibid., 1.8.

16 M. K. Čiurlionis apie muziką ir dailę. Vilnius, 1960, p.

279.

17 Marianne Werefkin. Briefe an einen Unbekannten.1901-1905. Köln,

1960, p. 19.

18 Marianne Werefkin. "Life in Art. From the Letters of Marianne

Werefkin to Alexej Jawlensky." Vilnius (in Russian), 1992, No. 2, p. 99.

19 L. Laučkaitė-Surgailienė. "Du žvilgsniai į miesto peizažą XX a.

pradžioje: Mstislavas Dobuzinskis ir Mariana Veriovkina." Mstislavas

Dobužinskis ir Lietuva. Vilnius, 1998.

20 M. K. Čiurlionis apie muziką ir dailę. Vilnius, 1960, p. 196.

21 Op. cit. Werefkin gave a lecture during a regular Art Society

meeting, held Saturdays, on March 22,1914. 1.20.