Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

Copyright © 2004 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 50, No.3 - Fall 2004

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas ISSN 0024-5089 Copyright © 2004 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Theater Review

Modern Love: Cezaris Graužinis's The Taming of the Shrew

Among the most talked about developments in the current Lithuanian theater scene is the emergence of director Cezaris Graužinis and his new "Cezario Grupė," a cadre of five young actors whose talents are rapidly attracting an enthusiastic following. Last season, Graužinis's production of Arabian Nights earned international praise for the director and a Lithuanian "Golden Cross" award as the year's best debut for the Cezario Grupė. This season, Graužinis and his former acting students are reunited in an enchanting production of Shakespeare's Užsispyrėlės tramdymas (The Taming of the Shrew), premiering September 17, 18 and 19 at the Lithuanian Youth Theatre in Vilnius.

Judging from the play's June 30 "preview" performance, the new production will be successful and well attended when it officially opens in the fall. On a midweek summer evening in the Lithuanian capital, the play drew a large and eclecticnotably youthfulaudience, vocal in its appreciation of both the director and his high-energy troupe.

In keeping with Shakespeare's rather lighthearted intent in this play, Graužinis makes certain that comedy always controls the action. From the opening moments, an atmosphere of playful melodrama prevails. The pace is quick and spirited, the musical score of Giedrius Puskunigis correspondingly exuberant. The audience thoroughly enjoys the central action of the playthe alternately humorous and poignant battle between the shrewish Katharina of Brigita Aršobaitė and Petruchio, her tamer, played by Julius Žalakevičius.

|

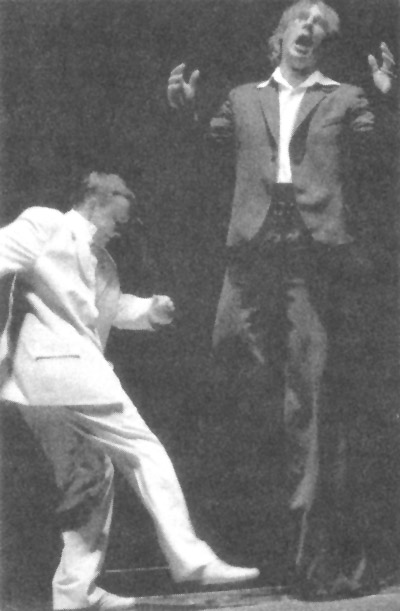

| Petrucio (Julius Žalakevičius and Grumio (Laisvūnas Raudonis) Dimitri Matayev photo |

The evening's unconstrained atmosphere is enhanced by elements of farce and slapstick. Petruchio's servant Grumio, played by Andrius Bialobžeskis, lumbers about on concealed stilts; he is an awkward, bungling giant who towers humorously over his diminutive master Petruchio. This physical contrastalong with the play's Italian setting, its depiction of marriage as a business transaction, and the suit-and-tie outfits of the play's male characterscasts the Petruchio-Grumio pairing as that of a stereotypical Mafia boss and his goonish bodyguard.

The play's Mafia motif works well and makes sense. Other directorial innovations, especially in the presentation of Petruchio, are more daring. Traditionally, the gentleman from Verona who tames the fierce Katharina is a supremely self-possessed character, exuding masculine charisma in a manner that satisfies Kate's inner longing for legitimate authority. When Petruchio appears at his wedding in outlandish attire, it usually signifies his bold defiance of social convention. In Graužinis's play, however, Petruchio appears at his wedding in almost no attire whatsoever. Bare to the waist in a white loincloth, he resembles an overgrown infant. In Shakespeare's text, Petruchio avers, "I am rough, and woo not like a babe." Graužinis obviously turns this line on its head, transforming Petruchio into a clownish squirt with a high-pitched voice and a tendency to make himself ludicrous. From this vainglorious Petruchio, the boastful recounting of courageous exploits"Have I not in my time heard lions roar?"becomes a parody of masculine prestige.

Through Petruchio, Graužinis may be attempting to outline an interesting contemporary turn in the battle of the sexes. Because Petruchio offers Kate the opposite of the masculine ideal, it is tempting to conclude that he is not forceful enough to account for or to justify the profound shaping of a will so formidable as Kate's. Kate's acceptance of Petruchio's authority, however, may simply mean that her needs are best answered by a combination of virtues in which traditional masculinity is tempered with offsetting traits-including a visible tenderness toward her that Zalakevičius manages to convey in several scenes. Within this updated standard of manly action, the chemistry between Kate and Fetruchio is palpable and believable.

|

|

Katharina (Brigita Arsobaitė) |

In a similar way, the hot-tempered Kate immediately becomes a sympathetic character, for it does not take long for a contemporary audience to understand that her anger stems from the expectations and limitations imposed upon her as an unmarried woman. This Kate begins the play as a witch and a sorceress, roles in keeping with her position as a woman tormented by antisocial rage. Though her acceptance of the marriage vow is appropriately presented as a traumatic and painful experience, Arsobaitė's Kate shifts convincingly into a mature, accepting demeanor that becomes the play's feminine ideal.

In contrast, Kate's sister Bianca, in whom an audience expects to see what Shakespeare terms "mild behavior and sobriety," is capricious, petulant, and calculating. In Shakespeare's text and in most versions of the play, her refusal to submit to her husband's will at play's end is subtly foreshadowed; here it is all but overtly asserted. It comes as no surprise when she rejects her newlywed Lucentio's summons in Act 5; she has already held her own in battles with Kate and forcefully dismissed the suitors Hortensio and Gremio. The courtship subplotspairing the romantic Lucentio with Bianca and the pragmatic Hortensio with the widowclearly convey the ominous long-term implications of such superficial relationships in contrast to the more solid Kate-Petruchio union.

Each of the three marriages that occur in Shakespeare's play are in some way commercial transactions, involving the exchange of significant property and large cash dowries. Graužinis, however, adds special emphasis to the mercenary motivations of the central characters. The two lines that elicit the loudest laughterPetruchio's urgent inquiry of Kate's father Baptista, "Kur pinigai?" (Where's the money?) as he prepares to marry Kate, and Petruchio's clever exaggeration of the dowry agreed upon by Baptistaare nowhere to be found in Shakespeare's text. These added lines leave no doubt that, even after he gets to know Kate, Petruchio's motives for marrying her are largely financial. When, however, Petruchio turns over his suitcase full of money to his new wife, the implication is that their strangely modern relationship somehow "works"that Petruchio is not completely selfish, nor is Kate as overmastered as she seems.

Overall, this Taming of the Shrew offers more evidence that the Lithuanian theater continues to enjoy a strongly creative phase. With directors such as Eimuntas Nekrošius, Oskaras Korsunovas and Cezaris Graužinis leading the way, young Lithuanians are flocking to the theatre in anticipation of productions that are thoughtful and dynamic in their treatment of both new plays and classics. This latest effort of Graužinis and the "Cezario Grupe" suggests that the high expectations of the new generation of theatregoers in Lithuania will continue to be met.

Patrick Chura