Editor of this issue: M. G. Slavënas

Copyright © 2005 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 51, No.4 - Winter 2005

Editor of this issue: M. G. Slavënas ISSN 0024-5089 Copyright © 2005 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

NIJOLË SAVICKAS WORK BY FIRE

Stasys Goðtautas

Nijolë Savickas with her son Antanas |

Nijolë Sivickas was born in Lithuania but lived most of her creative life in Bogotà, Colombia. Since most Colombians cannot pronounce her name Nijolë – because of the “J,” they call her Nicole or the mother of Antanas, the mayor. For six years (1995-1997, 2000-2003) her son, Antanas Mockus, was mayor (“alcalde major”) of Bogotà. At present, he is a candidate for the country’s presidency. Antanas’s sister Ismelda is a medical doctor. |

* * *

Nijolë began her artistic career as a painter and graphic artist in the Visual Art Academy of Stuttgart (Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste) in 1946–1950, with G. Gollwitzer and Willy Baumeister as her teachers. That is why, perhaps, she tended towards German expressionism – an international movement that began just before World War I, when chaos became a metaphor for the world. In Nijolë’s work we observe a lot of disorder vs. the logic of the classical world, because that is her world.

Just married in 1950, she came to Colombia to work as an artist in newspapers and magazines. Later she joined the studio of Lithuanian potter Juozas Bagdonas. When he left for the United States, she inherited the studio and dropped the brush and the printer to concetrate on the rich tradition of pre-Colombian artifacts.

For the next fifty years Nijolë worked with fire and clay, producing an immense number of art objects of diverse dimensions and weights. Some of them are so heavy, 200 to 300 pounds, that one has to ask how a petite woman can lift such heavy objects. Other structures and installations take up a whole room, and if they don’t fit, they continue onto the roof or into the garden of her home.

At the time of Nijolë’s arrival in Colombia, the country’s artistic milieu was very much molded by the socialist and indigenist movements. Then few foreigners started to work in abstract art, producing a mixture of Kandinsky and American abstract expressionism. By the 60’s the milieu had changed completely and Bogotà became an international centre of Western culture and art. Nijolë’s philosophy of art also changed, and with time her work became less realistic and more creative. She was fascinated by the infinite variety of clay that she herself dug up every week from the Andes foothills, and brought back to her studio, which is also her home. Like her skillful predecessors, the Chibchas and Quimbayas (Colombian indigenous tribes) she created imaginative forms and shapes with rich patinas and colors obtained through oxides and fired up to 1,030° C in the kiln. Her son helped her to install and improve it.

Her art grew out of Colombia, her new home. She abandoned her Lithuanian artistic heritage and submerged herself in the rich Indian and Mestizo traditions, yet did not completely forget her native land. She taught her son and daughter the language and history of Lithuania, and a respect for their heritage. She spoke to them only in her native tongue.

Nijolë’s works with clay, iron and rope is difficult to classify. She is a sculptor, a creator of structures and installations, a ceramist. She could also be called an artisan who enjoys her work for its own, as many anonymous amateurs do. I would classify her mainly as a sculptor who works with clay and creates complex art objects for posterity. There is a monumentality to even her smallest installations.

In most cases, her work is not beautiful (“I am not looking for beauty” she says). Her work is strong, sometimes grotesque, and fantastic. The collection of iron, clay, carbon, and earth reminds us of the primitive forces that give life and are limitless in space. They hang above us, they intrude on our intimacy, they are not easy to understand or to accept. They are what they are, and the artist does not care. She looks with disdain at our amazement, and she is the one who asks the questions. Her work defines her and she accepts that definition gladly because, after all, nobody can really understand her work better than she herself.

Her works – if we persist in calling them ceramics – has no utilitarian purpose, you can’t drink or eat from them. You can put them in some corner and admire them as works of art, you can interact with them, touch them, push them, make sounds. After all, they have been baked at over a thousand degrees Celsius, they will last, like a rock, forever. Nijolë has given clay the same nobility as stone, marble or wood. She succeeds where many have failed. Her hands enjoy kneading the clay.

The colors of her finished pieces are dark red, yellow, black, according to the choice of the clay, and sometimes from the natural reactions of the oxides and glazes during firing. She used to work with lead. Lately, because of her fragile health, the Department of Health has intervened and stopped her chemical adventures, but who is Nijolë to listen?

All of life Nijolë’s life work could be defined in three stages. The first phase is one of expressionist paintings and prints. These are too close to what she learned at art school and were never truly hers. She knew this and abandoned them with disdain.

The second period is a search that lasted almost twenty years. The change of continents and of language and culture had an impact on her, and it took her a while to decide what steps to take next. This was a very poetic period, with some great successes, but still very much under the influence of German expressionism and too close to indigenous art.

Nijolë was not happy with the results and finally, almost twenty five-years ago, she turned to creating objects that do not exist in reality because according to her, if they do, why bother to repeat them. It seems like such a logical reflection that Nijolë had to think about why she hadn’t thought of this before. Here we discover her as a philosopher, a thinker and poet. In one show in Medellìn, Colombia (1994) she asks: “What are my objects doing in a building? They are my works, they look at people who come and go.“ For a while she refused to give them titles, but for practical reasons had to give in. The titles are poetic, all part of a puzzle that becomes the great symphony that is her entire work.

Although after her first exhibition in the noted Hall of the Biblioteca Nacional of Bogota in 1955, Nijolë swore not to exhibit anymore, she broke her oath eight years later, and in her fifty years as an artist has had more than twenty individual exhibitions around the world, participating in over a hundred collective shows in the United States, Lithuania, France, Australia, Puerto Rico, Venezuela and Ecuador.

* * *

The following interview with Nijolë Sivickas was written a few years ago by her son Antanas Mockus. It is a fictional interview created by Antanas, probably when he was President of Universidad Nacional de Bogotá. It is a short conversation, a beautiful piece of poetic truth.

Antanas. When you arrived in Colombia, did you bring your own views?

Nijolë. No. When you emigrate to a country you have to forget everything. Your profession, everything. An émigré is an émigré. His or her history is left behind.

A. When did you forget your status as an émigré?

N. When I started to communicate with nature and people.

A. When did this happen?

N. After some seven or ten years: When one forgets two words, “refugee” and “émigré,” even though one can never forget them totally.

A. How did you see Bogotá when you first arrived?

N. A lot of people with black hair, black dresses, a lot of ruanas, shawls and hats. I worked for several years as an artist for newspapers and magazines. I also decorated display windows. In other places, the émigrés had to work in forests or in the coal mines...

A. Your sculptures live in harmony with your feelings or coincide with the few moments of great expectations of the country, such as the process toward peace under Belisario Petancour (President of Colombia from 1982 to 1986) or the constitutional assembly called by César Gaviria (president from 1990 to 1994).

N. My work does not reflect hope, but I admit that made me feel better.

A. What do you like here the most?

N. The mountains.

A. How about the people?

N. You can’t understand them. They are always new. You are never bored with them. You can never understand a Colombian completely. They are always very skillful, very capable, very gifted. And also sentimental. But not very clear.

A. You mean they are unpredictable?

N. I don’t know if it happens in all of Latin America, but certainly it happens in Colombia. When you encounter a rupture of a relationship or you don’t keep your promises, the European or North American does not forget. He keeps reproaching.

But – changing the subject – can I ask you, my son, why you helped me in my art studio, in my work, in my exhibitions?

A. Because I did not know what to do with myself and I felt close to you. Your work seemed important to me. I felt my help was useful. At the same time I learned a lot. There is originality in your work.

N. Was there a fear of being part of everything? When they threw me out in some places, I did not look very good. You instead did better, after some fiasco, you came back stronger, and became famous.

A. What do you think of becoming famous? Why do you classify people or their trajectory as something “up” or „down”?

N. Because that is the way it is. Some people do better, others worse.

A. Could you have a more horizontal vision?

N. That’s impossible. If you don’t have it...you can’t rise. It is the word querer, which means I want. I want is a very important word. If you don’t have the word querer, if you cannot say “I truly want... I want to write, I want to do this or that,” then everything ends.

A. What do you want to accomplish? What would you like to see in your work?

N. That it would be good. That everything I make would be good, but that is impossible. There are people who think that everything they do, they like.

A. But could that mean that you demand too much of yourself, that you learned to make demands of yourself from your parents, your teachers?

N. No. But now, again, I would like to know about your life.

A. My responsibility now is enormous.

N. A few days ago, you used one short phrase which expressed more than anything else. I can’t repeat it; it was too strong. It was in reference to the water supply, Bogotá without water. A thirteen-year-old boy heard the curse. I asked him why you spoke in such strong language. He answered, “You taught him, he did it because of you.” I spoke little with the youngster about these things. But they listen. They remember.

Translated from the Spanish by Stasys Goßtautas

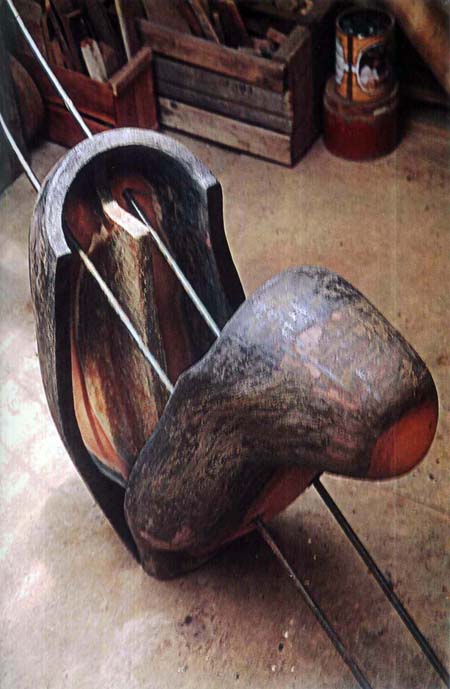

Nijolë Savickas. "I opened",

terra cotta, pigments and metal, 91x137x35 cm 1997-1999

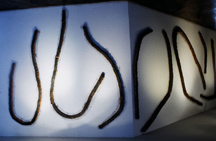

“Lines,” installation, various dimensions, maximum 191 cm, mesh,

high-fired clay, oxides, 2000.

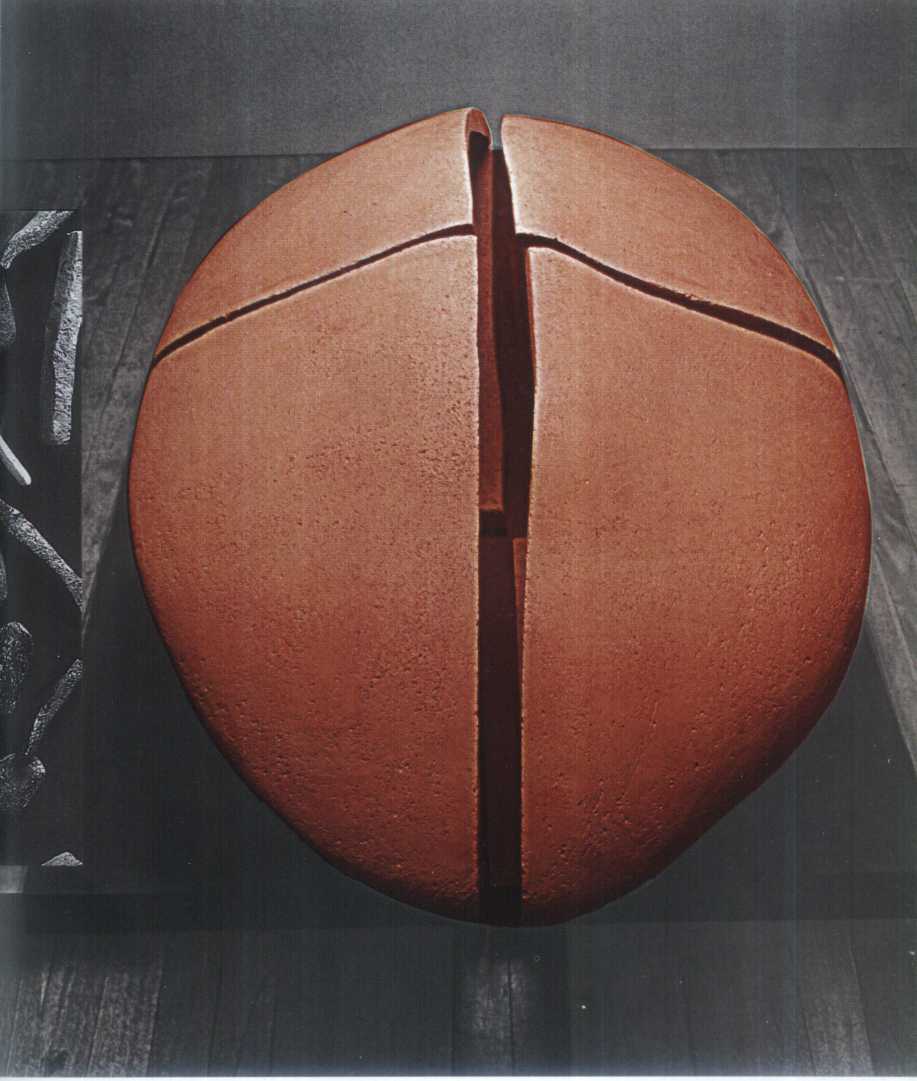

“Broken seed,”

high-fired clay and metal, 65x116x79 cm, 1997–1999

“Nucléolos,”high-fired clay, oxides, pigments and metal,

181x116x10 cm, 1999–2000.

“Nucléolos,”detail. |

“Nucléolos” (detail). |

“Press,” high-fired clay and metal, 1992.