Copyright © 2006 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 52, No.1 - Spring 2006

Editor of this issue: Stasys Goštautas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCE

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2006 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 52, No.1 - Spring 2006 Editor of this issue: Stasys Goštautas |

INFLUENCES OF "MLODA POLSKA"

[YOUNG POLAND] ON

EARLY ČIURLIONIS

ART

RASA ANDRIUŠYTĖ-ŽUKIENĖ

Rasa Andriušytė-Žukienė, Chairman of the Department of Fine

Arts at Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, Lithuania. Her mono-graph

“M.K. Čiurlionis: tarp simbolizmo ir modernizmo”

[Čiurlionis: between Symbolism and Modernism] was published in 2005.

To determine more precisely what influenced Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis’s (1875–1911) creative work, his themes and imagery, it would be useful to become better acquainted with Polish art – both its modern and Romantic underpinnings, which were largely formed at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. Having quickly absorbed the new developments in Western art at the beginning of the latter century, Polish modernism was one of the sources of Čiurlionis’s familiarity with this art. Are there similarities in Čiurlionis’s creative output to the works of some of Poland’s artists at the time? If we find such features, we can argue that Poland’s art scene – the modernistic “Mloda Polska” [“Young Poland”] movement – was the first step on the Lithuanian artist’s path to modernism.

Various creative individuals developed the “Mloda Polska” movement. It was not a unified movement in a stylistic sense, but really the creative endeavors of diverse outstanding individuals, which is why the late-nineteenth-, early-twentieth-century period of Polish painting is varied, not monolithic. Particular groups did not form in Poland, nor were there obvious trends. In such a case, the attempt to identify specific inspirations for Čiurlionis, flowing as much from Western as Eastern culture, is a complex and challenging task. Nevertheless, striving to understand the sources of Čiurlionis’s art we cannot ignore the work of his contemporary Polish artists because during the turn of the century members of the “Mloda Polska” circle created works close to the artistic quality of the art of Western Europe. The “Mloda Polska” group of writers and artists, having become the center of Polish symbolist art, were influential in cultural centers such as Warsaw, Lvov and Vilnius.

Čiurlionis’s Early Creative Works

We can assess the early stage of Čiurlionis’s work (1902-1906) from that part of his legacy – letters, drawings, and prints – housed in the National M. K. Čiurlionis Art Museum (NCAM) in Kaunas. This period showed especially significant originality in his style and the development of his artistic world. It was a time when the artistic atmosphere at the beginning of the century and Polish art or the works of foreign artists seen in Warsaw could have exerted a great inlfluence on him.

Currently, the NCAM holds eight notecards drawn by Čiurlionis, dated 1902-1904, some of which were done before the beginning of his art studies. The motifs are not very different from those used to create a symbolic language of art by Čiurlionis’s contemporaries in almost all European countries. The brightly colored, still somewhat naïve pictures have interest as Čiurlionis’s first artistic attempts, as sketches for future compositions, and as typical reflections of symbolism and the modern spirit. The compositions of the notecards reveal the aspiration to create symbolic, fantastical, and even somewhat frightening scenes.

During his studies at the Warsaw School of Fine Arts, Čiurlionis became interested in the fluorofort technique popular in Poland at the time. The graphics he did using this method for a few years (1905-1908) are some of the most unusual productions in Lithuanian graphic art. This technique also interested Leon Wyczulkowski, Stanislaw Wyspianski, and Ferdynand Ruszczyc.

Čiurlionis’s work stands out for its more firmly constructed composition and prominent motif – the scene is a church tower against the background of snowy city rooftops. From a technical standpoint, Čiurlionis’s effort is not the most accomplished, but the simple majesty of the motif and composition catches the eye, with some strokes accurately creating the effect of size, space, and distance. Compared to the compositions of the notecards, Čiurlionis’s “A Snow-Covered Village” housed in Kraków and other fluorofort pieces of his in the NCAM seem truly realistic works, although they were done later, during 1905-1906. The question arises as to why nature is depicted so accurately in these fluorfort works, done at least two years after the creation of the early symbolic paintings and graphic pieces (for example, “The Funeral Symphony,” 1903; “Peace,” 1903-1904; and the cycle “Wrath” and book-cover designs, all during 1904). Why did Čiurlionis then return to the simplest of nature studies? The Warsaw Art School conveyed certain academic principles. This school stood out for a somewhat unusual system of training artists: It paid great attention to the applied arts. As opposed to many other schools in Europe and Russia, the Warsaw school did not consider the academic drawing of plaster models of antiquity to be a very important discipline. Moreover, the students would frequently paint outside, plein air. Perhaps, this contact with such academic principles explains the return to nature studies in Čiurlionis’s fluoroforts of 1905-1906.

All of Čiurlionis’s prints of the time still evidence a sincere amateurishness, a lack of artistic maturity. This caused a certain stylistic indecisiveness, a balancing between realism and modernism. Čiurlionis’s graphic pieces show a clear observation of nature, sometimes enriched with elements of animistic fantasy. Thanks to these elements, some of the graphics (“Bell tower” and the colored monotype “Fantasy,” 1906) are expressive works.

Elements of a Romantic Imagination

In spite of a stormy process of change and the attempt to modernize, Polish painting of the nineteenth century is marked by Romanticism. For Čiurlionis’s emotional attitudes and creative works, like for the first phases of Polish mod¬ernism, the sources of symbolism are Romantic. One of the major features of the Romantic movement was a pantheistic worship of nature, considered the totality of creativity. After the Age of Enlightenment (in Poland, after the period of positivism), the Romantic movement foregrounded the power of emotion, imagination, and intuition to first place. Romanticism as well as modernism rests upon a similar basis – the principle of subjective interpretation, which is why it is uncommon to differentiate with which movement – romantic or symbolist – Polish painting or the oeuvre of individual artists is allied.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Polish painters and the young Čiurlionis were influenced by Polish Romanticism. The Vilnius Romantic school and its poets wrote about Lithuania’s past; these writers included Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Slowacki, Józef Ignacy Kraszweski, and Cyprian Kamil Norwid. According to the literary scholar R. KarmalaviČius, Lithuanians who studied in Poland at the beginning of the twentieth century, namely Sofija Kymantaitė, Juozas Albinas HerbaČiauskas, and Adomas Varnas, were true “apologists for the Romantic spirit.” Radoslaw Okulicz-Kozaryn has closely analyzed the inner bond between Čiurlionis’s creative output and the poetry of S¬o-wacki. In his opinion, Čiurlionis mined ideas from Slowacki’s King-Spirit, which the poet’s countrymen were un¬able to adopt even if they had tried (Okulicz-Kozaryn, 2003, 40-68).

The Romantic imagination, the part of the imagination as a type of envisioning, a type of psychological stress (Juszcak, 1997, 14), is the common denominator of many late-nineteenth- century artists, including Čiurlionis. It would not be totally accurate, however, if we confined ourselves solely to observations regarding commonality. Comparing the work of Čiurlionis to that of the Polish artists, it is evident at first glance that he is different, aesthetically and stylisti¬cally more original, not similar to and not to be confused with any painter of the “Young Poland” movement. And here arises the question of Čiurlionis’s modernism.

The

Historiosophical Character of Art and the

Concept of National Art

At the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth, Polish art showed a clear, pervasive historiosophical character, under the influence of the patriarch of nineteenth-century Polish painting Jan Matejko, longtime president of the Kraków Art Academy. The attitude to historical themes and history itself in Polish art at the beginning of the twentieth century was already quite altered; history was understood as the domain of emotions, moods, and generalized experiences (Szacki, 1971, 68-69).

In such a system of experiences the functions of art are comparable to the function of myth: the past is reconstructed according to the laws of fantasy, and art contributes to the strengthening of tradition, according it a greater worth and prestige. (Malinowski, 1958, 522). In this urgent awareness of history, Čiurlionis is quite close to Polish painters because the motifs of antiquity and the past, the search for spiritual ties with the past, and “making the past current” are especially evident in his mature works: “Eternity,” 1906; “The Altar,” 1909; “Fortress,” from “Fortress Fairy Tale,” 1909; “The Past,” 1907.

In addition to history, in the sense of the whole past instead of an individual event, Čiurlionis’s work evidences his interest in Biblical stories, the Orient, and the fairy tale as a type of painting. One cannot ignore, however, the many differences. Many Polish painters would constantly return to the storehouse of historical facts and legends, giving their paintings nuances of a primitive nationalism and subjective symbolism. If, for example, in the work of Stanislaw Wyspianski the past emerges as symbolic interpretations of historical facts or actual concrete scenes of Wawel Castle, the Wysla, or Kraków, in Čiurlionis’s compositions the past is revealed on the mythical or archetypal plane.

The Polish painters limited themselves to a national romantic program most important to them at the time. Heroic poems seem to be told in painting; the work has a clear purpose – the nation and its specific past, the awakening of a national spirit and consciousness. Nationalism was also important to Čiurlionis, as is especially evident during 1906-1907, when paintings with Lithuanian motifs and themes appear in his work. Judging from his letters to intimates at this time and from his earlier work, such national concerns were not evident in his thinking around 1900, during his studies in Warsaw and Leipzig. It turned out, however, that Čiurlionis quite soon experienced spiritual upheavals based on nationalism. A more critical attitude regarding the Poles must have developed. On returning to Warsaw, he became involved in Lithuanian organizations. In his Warsaw circle of friends, no one considered him a Pole. Thus it is not remarkable that Čiurlionis’s artistic path begins with themes broader than nationalism, begins with a feeling of a more generalized Romantic spirit, common to Poles, Germans and Scandinavians.

The Significance of Mood and Nature Scenes

The primary aspect of painting at the turn of the century was mood. In Polish painting at the beginning of the twentieth century this aspect was as important as the symbolic meaning of a work. The conveying of a mood was always linked with scenes of nature, since nature was the theme of major interest to Polish painters. Manifestations of the natural world – most frequently a panoramic view with clouds or a mysterious, misty chamber motif – are closely observed by the painters, seeking in them the echo of human psychic states and interpreting a landscape depending on those inspirations from nature. Nature is understood as the source of spiritual emanations, which is why landscapes are such an important genre.

Aleksander Gierymski formulated the “mood landscape,” which is not so much the definition of a natural landscape as of a compositional one: “Stimmung is the creation of a painting from feeling and memory” (Juszczak, 1997, 16). The mood is comparable to the artistic content: the mood is sought by simplifying the composition and motif – sometimes to a few perspective lines and matched colors (Popowski, 1900, 4). In Polish landscapes the most prominent effect is of emptiness, presupposing the moods of melancholy and pessimism, considered by critics of the time as the most typical features of Polish landscapes. Characteristic motifs are fields of grain, moonlight on the beach, the bends of rivers and wide meadows, whose emptiness is sometimes underscored by a lone tree or figure.

Autumnal scenes were especially popular in Polish painting of the time because of the association of dying plant life with the passage of time and temporariness. Scenes of autumn are generally rare in Čiurlionis’s work. As opposed to the Poles, emptiness and moods of sadness and melancholy are not the most characteristic of the Lithuanian artist. But the resignation of “Young Poland” can be found in Čiurlionis’s work “Sonata,” which has signs of Romanticism and musical structure.

Čiurlionis’s triptych “Raigardas” (1907) is filled with moods different from those of many Polish painters: not pessimistic, grim or frightening, but comforting and harmonious. Composing lines and patches of color, he finds a balance between untamed nature and its realistic depiction and “cultivated” meadows and grain fields (along with very decorative use of color) in a later part of the triptych. Such an observation allows the inference about the search for expressing a unified, harmonious world in this painting.

Because nature scenes in the work of Polish landscape painters are understood as corresponding to the inner states of human beings, the depiction of persons becomes insignificant. In this regard, Čiurlionis is somewhat similar to the Poles. People are rarely found in his paintings, and if present they are depersonalized, on a smaller scale, frequently in poses of praying or worshipping. People are so rarely depicted in Polish painting at the beginning of the twentieth century because of the primacy of pessimistic moods and a similar attitude toward the human being. This observation cannot be unconditionally applied to Čiurlionis’s work because in his compositions the human being is most often given the role of worshipper or herald of news.

Iconography and Motifs

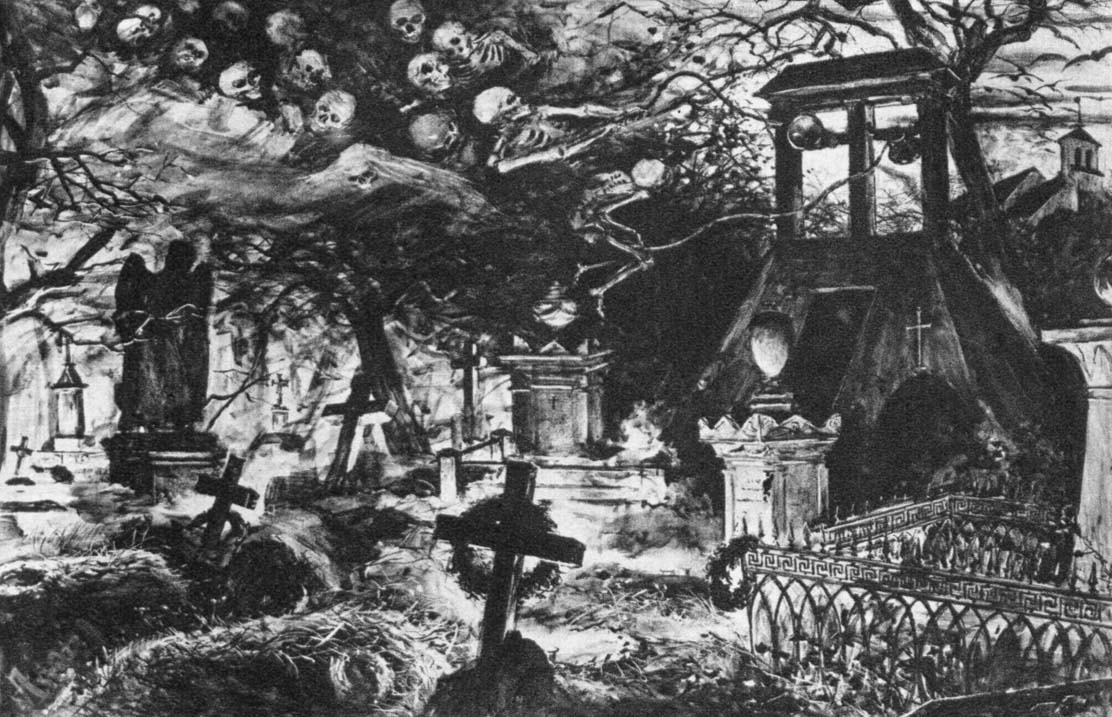

In order to understand the symbolism of the scenes in the paintings of “Young Poland,” it is necessary to consider the meanings of the most popular iconographic motifs. The paintings of these Polish artists are marked by a particularly distinctive iconography, influenced by a romantic and symbolic worldview. Regardless of the rather realistic method of portrayal, the motifs were given a clearly symbolic meaning. Especially popular were iconographic motifs that seemed to express the quintessence of the abstract fear and threat felt at the end of the nineteenth century.

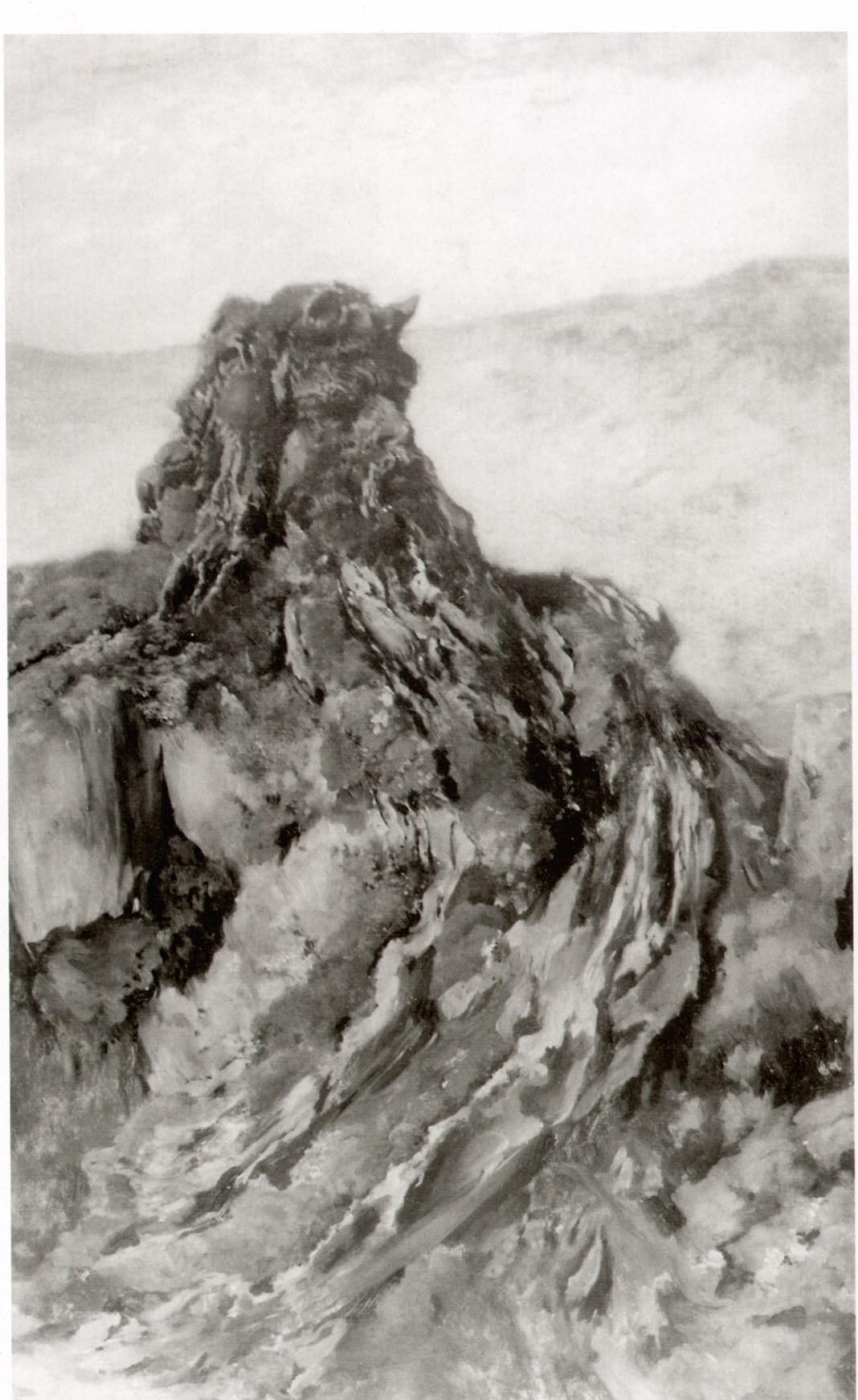

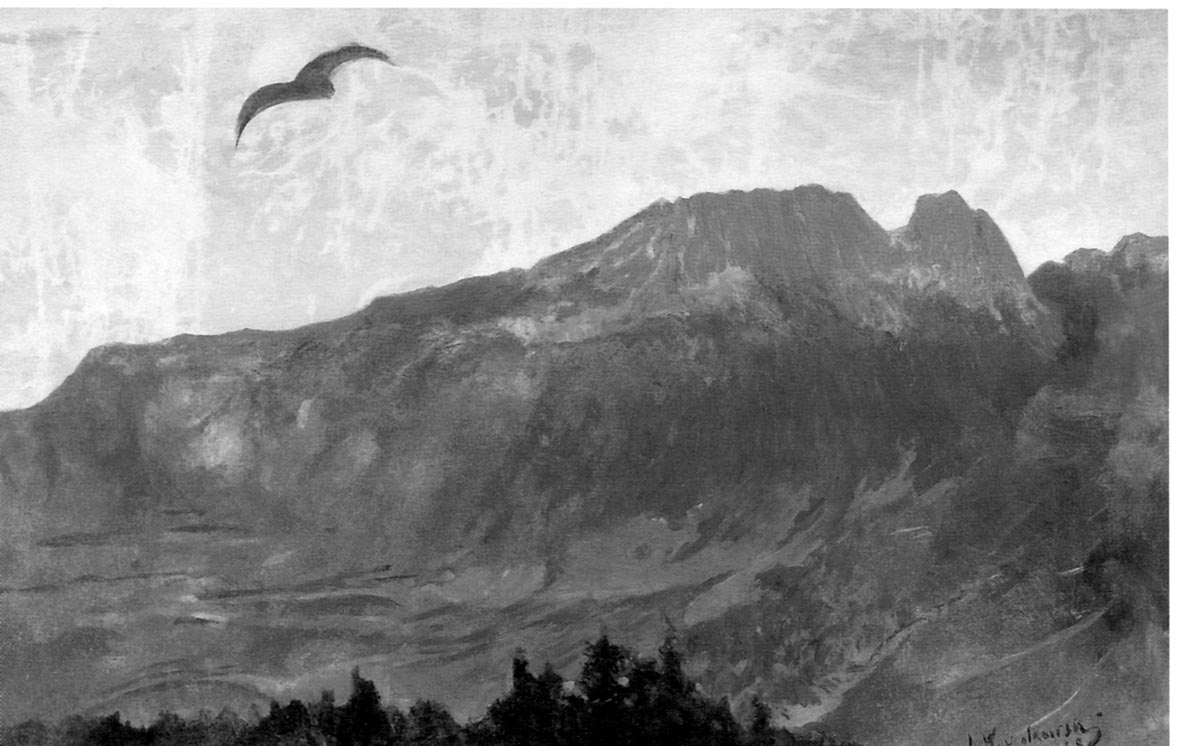

Another range of moods was available to the Polish painters from their fascination with mountain atmosphere and the constantly newly “discovered” Tatry Mountains. The silhouettes of ancient warriors are discovered in mighty cliffs; in a larger sense, in several paintings steep cliffs symbolized the dormant vital forces of nature.

L. Wyczólkowski’s “Giewont at Sunrise,” 1898, and “Kosciuszko’s Hill,” 1898, with Čiurlionis’s “Mountain,” 1906, are linked by similar motifs – a mountain, a bird, the sun. Both artists give an anthropomorphic shape to the silhouette of their mountain. But in Wyczólkowski’s painting the silhouette of the mountain cliff – a gigantic figure of a reclining knight – is a direct allusion to the Polish legend of King Boleslov the Brave’s fossilized knights, who can be awoken only by the regaining of national independence. The form of Čiurlionis’s “Mountain,” similarly to the works of many Polish artists, also reminds one of the profile of a living being. Čiurlionis, however, not only avoids specificity, but also generalizes: he seems to hide the two-fold meaning and make it less visible at first glance.

Comparing Wyczólkowski’s “Giewont” to Čiurlionis’s “News” (1904-1905), regardless of the same motif, reveals one principal difference. In the clear contrast of colors and lines, Wyczólkowski stresses the opposition of earth and sky. Čiurlionis pays most attention to conveying the illusion of sunlight, the medium of air, space, and flight. In “News” he is interested not so much in the multiple meanings of a single motif as in the semantics of a general, abstracted scene. We could say that Wyczólkowski created an essentially historiosophical landscape, while Čiurlionis pro¬duced a harmonious thematic composition. “News” is first a reflection of a pantheistic worldview, linked to the aesthetic of Romanticism. Wyczólkowski’s historical proposition is also linked to Romanticism, although his past, like historical time for the German Romantics, is the Middle Ages, specifically up to the campaigns of Boleslov the Brave. Wyczólkowski’s landscape is also an expression of a national consciousness and a love of country. Čiurlionis includes other aspects of Romanticism, the emotional significance of nature and the pondering of human existence and “eternal change.” It must be stressed that the sensitivity to the past in both works shows the habit of historical reflection

Unlike the Polish works, Čiurlionis

likes to compose his paintings using a sun motif. But like the Poles,

he also uses an analogous method of conveying light, underscoring its

presence with a painstaking drawing of a reflection or a falling

shadow. The paintings “The Past” and

“Raigardas” are typical examples of this technique,

appropriate to the principle of early-twentieth-century Polish art to

content oneself with the portrayal of the sun’s light, while

the motif of the sun itself, even during a summer day,

“remains beyond the canvas.” (Charazinska, 1997, 41). The sun, signifying

secrecy and danger, is a means of dictating the landscape’s

mood.

In addition to fatalistic, threatening, and mysterious scenes,

nineteenth- and twentieth-century Polish painting shows an aspiration

to harmony that is also linked to the searches for mood. The idea of

expressing harmony in painting influenced the principles of composition

and of the very motifs. Most often, harmony is linked with scenes of a

garden or park. When painting garden motifs, the Polish artists most

frequently convey a purely impressionistic fascination with the light

and color pulsating in nature.

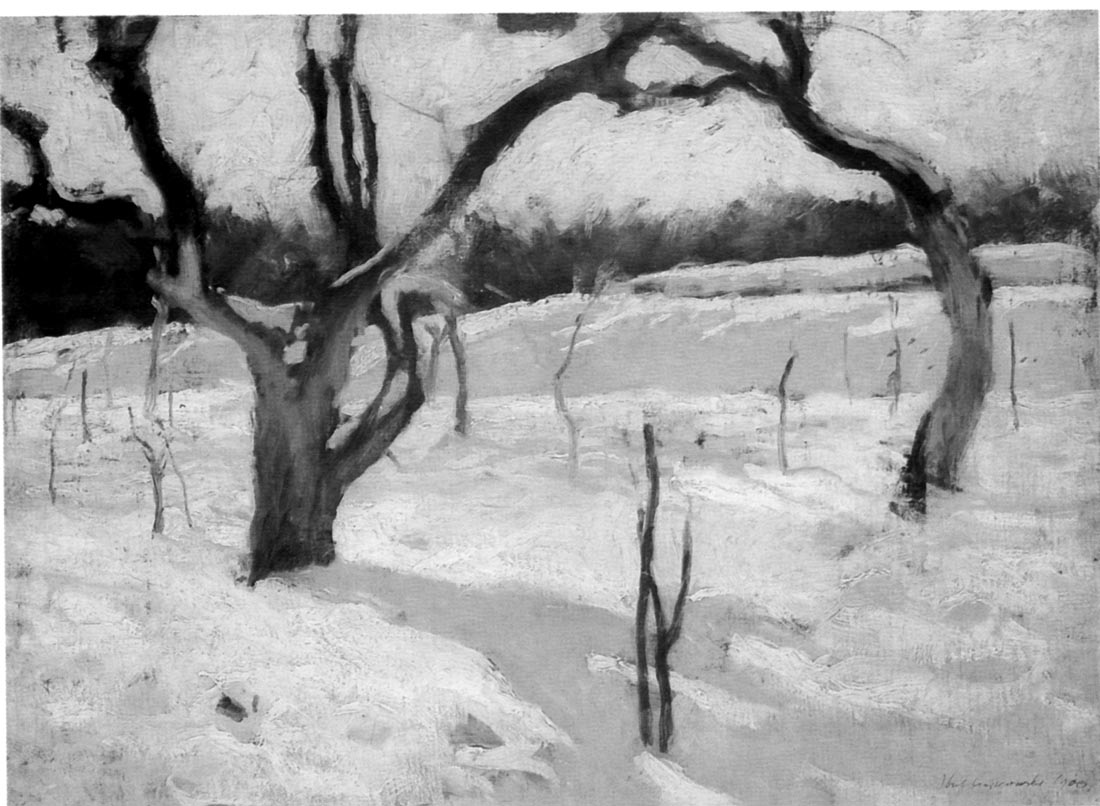

In many of Čiurlionis’s summer études there is free improvisation with various methods of painting, using technical effects (“Summer” and “Spring,” both 1907). Although it is not difficult to notice that these quite strongly rhythmical études are dominated by a conception that is somewhat different from that of the Poles. In Čiurlionis’s compositions with garden-park plant motifs, the primary note is the contem¬plation of nature; and he achieves the idea of a harmonious “ideal landscape,” not so much by looking for a “pretty site,” but by using a certain, usually symmetrical, composition and paying much attention to the architectonics of the painting (“The Little Yard” and two paintings called “Spring,” all 1907). To early-twentieth-century painters, enclosed scenes of nature seemed close to the ideal of harmonious beauty. Especially in Čiurlionis’s graphics we find many signs indicat¬ing the similarity of his artistic thought during 1905-1907 to that of such Polish painters as T. Rychter (“Trees in Winter,” 1904) and K. Mondral (“Young Apple Tree,” 1913). This is evident in the choice of an apple motif and a marked predilection for winter scenes.

Winter scenes play a significant role in Polish painting because the theme is particularly poetic – provoking lyrical, decorative choices. Winter scenes allowed not only a certain symbolic program, but also the possibility of formal compositional experimentation using white and black, the contrasts of light and dark colors. The most noted example is F. Ruszczc’s “A Winter’s Tale,” (1904). Many Polish painters approach winter motifs almost impressionistically, paying great attention to the vibration of shadows and light. The most frequent motifs chosen are a garden or individual trees. Using the fluorofort technique, Čiurlionis produced a few quite realistic winter scenes (for example, “Ribiniškės,” 1905-1906). Unlike the above mentioned Polish artists, he, while engraving yard and garden scenes, does not concentrate on problems of plein air, but focuses his complete attention on composition and the expressivity of black-white patches.

In Čiurlionis’s “Winter” Cycle (1907) the moment of change is clearly accented, and winter is presented as an inseparable part of the great cycle of change in nature. The various enclosed parts of “Winter,” unlike Wyspiaˆski and Ruszczyc are not static nor decoratively flat. Each part of the cycle shows a dynamic process, a change of rhythm and the transformation of elements. Čiurlionis’s cycle stands out strongly for its abstract space and its enlarged motif, as if the artist had observed from very close. The Polish painters liked a specific type of painting – a study of a lone plant or flower given symbolic significance. A plant on a large scale, seen against the background of a high horizon – such a composition could have been one of the prototypes for Čiurlionis’s “Winter” composition.

The second painting of the “Winter” cycle, with its dominant verticality, is most reminiscent of Ruszczic’s “A Winter Tale.” The major difference between them is that in the Čiurlionis cycle one does not see a sentimental worship of nature, but rather an emphasis on the elemental force of the natural process.

The cloud motif, even in bright summer landscapes, created an atmosphere of danger and fear. The Polish painters were without a doubt committed to this natural manifestation that stimulated the imagination. They liked compositions where the sky dominates a narrow strip of land or a river, or, conversely, the placement of the horizontal line is manipulated in the painting. They are “pure” landscapes saturated with a mood of emptiness and quiet. Čiurlionis much more boldly changes the clouds’ shapes, making them anthropomorphic creatures and creating individual scenes or even developing a complete story line (“Thoughts,” 1906; “The Prince’s Journey,”1907). His intentions are different also. Only in “Daytime,” from the “Full Day” cycle (1904-1905), one senses a certain mood of unease, more typical of the Polish painters, when the clouds seem to be the personification of danger.

Painters at the beginning of the twentieth century still acknowledged the divine structure of the world, but the conception of a non-monotheistic god evoked an almost mystical relationship with the eternal primordial elements – the earth and sky. Many of Čiurlionis’s works, as well as those of Stabrowski and Ruszczyc, are based on the oppositional juxtapositions of earth and sky, light and dark. We see a starkly dramatic realization of the opposition of earth-human-sky in Ruszczyc’s painting “Earth,” 1898. So is Čiurlionis’s “The Sun is Passing the Sign of Taurus” from his “Zodiac” cycle (1906?-1907) is like this too. Although the visual motifs coincide, one must note that Čiurlionis does not emphasize the contrast of the earth and the sky but, conversely, the unity and harmony of these elements. To maintain this effect, he does not include a human figure, although the other paintings of the Zodiac cycle contain one. In Ruszczyc’s painting the figure and the movement of a farmer make the scene more spontaneous, and the composition also gets a narrative flavor.

Čiurlionis and Ruszczyc are linked also by the princi¬ples of ideas and aesthetics. A tendency toward patriotic Romanticism is generally characteristic of Ruszczyc’s work, bringing him closer to Wyspianski and further away from Pszybyszewski and Gorski (for whom the aspect of patriotism in art conflicted with art’s very essence) and also from the “peasant genre” of painting of Sichulski and Tetmajer. The human figures painted by Ruszczyc, like the figures in Čiurlionis’s “Zodiac,” are full of the moods of the landscape, namely, mood is the most significant for both artists, concentrated to the point of a symbol. The difference is that Ruszczyc’ symbols are based on folkloric-mythological archetypes, while those of Čiurlionis, in regard to the “Zodiac,” cosmic symbols. On the whole, Ruszczyc in his work realized a positive patriotic program and it seems that as a teacher at the Warsaw School and a painter of the Vilnius region, he influenced Čiurlionis, whose artistic repertoire also included topics of a much wider nature. In both cases, however, it is obvious that the national and the artistic consciousness depended on each other. Neither Čiurlionis nor Ruszczyc were prone to analyze people’s inner problems, to psychologize. They searched for spirituality, not in the psychological analysis of inner life, but in nature and folklore.

Conclusion

There are similarities and differences between the works of Čiurlionis and the most important turn-of-the-century Polish painters. The essential questions of creativity, national and transcendental spirituality, self-expression and originality are relevant to the Polish artists and also to Čiurlionis, who was formed in the same environment. Also common to both is a gradual search to overcome naturalism – a desire to come closer to ideal, metaphysical domains.

Regardless of the common basis of their ideas and the romantic imagination, we cannot consider these manifestations as equivalent. Čiurlionis’s work does not allow for his easy inclusion in the “Young Poland” circle. In what lie the difference and the incompatibility?

Markedly more than his Polish colleagues, Čiurlionis was able to move his artistic work from the level of earthly life to the metaphysical world, which is why his artistic language is more abstract. Compared to the artists of “Young Poland,” he was able to create works in new forms, in truth, somewhat surpassing them in time: the turning point in his work occurred during 1906-1907, while the most creative period of the “Young Poland” movement was already over at that time. While Čiurlionis’s images, like those of the Poles, were quite concrete, their semantic meanings are not analogous because their motivation is different.

The Polish artists were not yet able to renounce conclusively a conception of art that was of the Enlightenment and historiosophical. Recent historical events cloaked in a mist of emotion and mysticism and rounded out with allegorical and symbolic figures, remained the singularity of the work of the major “Young Poland” symbolists. Although we speak about Polish symbolism as a component of Polish modernism, it is clear that it arose in the field of Romantic art and aesthetics. But rhetorical speech and prophetic intonations would be difficult to find in Čiurlionis’s work. Yet Paul Verlaine called for the elimination of rhetoric, and Jean Moréas criticized didacticism and declamatory intonations in poetry. Although on the whole Romantic features were prominent in the aesthetic consciousness of both Čiurlionis and the Poles, in his mature work, marked especially by the principles of calm and anti- rhetorical language, the Lithuanian artist appears quite modern. He expresses the language of plastic art strongly. Not only the composition, but also technical “inventions” become the source of a painting’s beauty and the objective of the interpretation. The very language of art is an important artistic goal. Expressing this language, Čiurlionis advances more deeply into modernism than any of his contemporaries in Warsaw or Kraków.

Can we conclude then that the presence of Western modernism in Čiurlionis’s work is stronger than that of neoromantic “Polish modernism”? Regardless of the contact with modern artistic language, it is evident that the common features of Čiurlionis’s work – individualism, lyricism, symbolism, transcendentalism, nationalistic goals – are still Romantic features, characteristic, by the way, not only of Polish but also Russian, Czech, and Scandinavian artists. It is possible to say that the “Young Poland” painters understood theoretically the basic principle of the aesthetics of modernism – that creativity is first of all an aesthetic value – although in practice they did not discover new ways to realize it, maintaining the naturalistic-realistic style in their works. Čiurlionis, on the contrary, did not intone the “art for art’s sake” slogan. In practice, he approached the goal of Polish modernism, concentrating on plastic problems and on changing the form of a work. And that is the most significant characteristic of Čiurlionis, distinguishing him from the Polish artists, while at the same time allowing a discussion about the Lithuanian artist’s connection with the “Young Poland” movement.

Thanks

to Aušra Kubilius

for helping translate and edit this paper.

Ed.

WORKS

CITED

Charazinska, E. Pejzarzy

rodzimy. Koniec wieku: Sztuka polskiego modernizmu 1890–1914.

Warszawa: Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie, 1997. 37–48.

Goštautas, Stasys.

“The Fantastic Art of Čiurlionis.“

Lituanus, Vol. 29:2(1983) 52-64.

———, ed. Čiurlionis: Painter

and Composer, Collected Essays and Notes, 1906–1989.

Vilnius: Vaga, 1994.

Gryglewicz, T. Malarstwo Europy srodkowej

1900–1914. Tendencje modernistyczne i wczesnoawangardowe.

Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloˆski, 1992.

Juszczak, W. Stanislawski.

Warszawa: Panstwowe

Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1972.

———. Teksty o malarzach: Antologia polskiej krytyki artystycznej.

1890–1918. Warszawa: Auriga, 1976.

———. Modernizm polski. Koniec

wieku: Sztuka polskiego modernizmu 1890–1914.

Warszawa: Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie, 1997. 13–20.

——— and Liczbiˆska, M. Malarstwo

Polskie. Modernizm. Warszawa: Auriga, 1977.

Juščiakas, V. Apie

simbolizmą, ekspresionizmą, erdvę.

Čiurlioniui 100. Compiled by J. Bruveris. Vilnius: Vaga, 1977.

130–137.

Koniec wieku. Sztuka polskiego modernizmu 1890–1914:

katalog wystawy. Ed. E. Charazinska,

Warszawa: Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie, 1997.

Kozakowska, S., Ma¬kiewicz, B. Malarstwo polskie od

oko¬o 1890 do 1945 roku. Kraków: Muzeum Narodowe,

1997.

Krzysztofowicz-Kozakowska, S. Sztuka kręgu

Sztuki. Towarzystwo artystów polskich „Sztuka,“

1897–1950. Kraków: Muzeum Narodowe, 1995.

Krzyzanowski, J. Neoromantyzm

polski 1890–1918. Warszawa: Zakù. narod.

im. Ossolinskich, 1971.

Malinowski, B. Szkice z teorii kultury. Warszawa: Panstwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1958.

Matuszewski, I. Slowacki

i nowa sztuka (Modernizm). Wyd. II. Warszawa, 1904.

———. “Malarstwo japonskie.” Tygodnik

Illustrowany. (49)1900.

Miloszas, Cz. Lenkų literatūros

istorija. Vilnius: Baltos lankos, 1997.

Okulicz-Kozaryn, Radoslaw.

“The language of Radiant Love... .“. Lituanus,

Vol. 49:4 (2003). 40-68.

Podraza-Kwiatkowska, M. Symbolizm i symbolika w poezji Mlodej Polski.

Kraków: Universitas, 1994.

Siedlecka, J. Mikolaj

Konstanty Čiurlionis:

Preludium warszawskie. Warszawa: Agart, 1996.

———. “Warszawskie lata

Miko¬aja Konstantego Čiurlionisa,” Lithuania.

1995. No 3. (16). 118–121.

Szacki, J. O tzw. historyzmie w naukach spo¬ecznych.

Metodologiczne problemy

teorii socjologicznych., Ed. S. Nowak, Warszawa: Panstwowe wydawnictwo naukowe, 1971.

67–83.

Wierzchowska, W. W¬adys¬aw Podkowiˆski.

Warszawa: Sztuka, 1957.

Witkiewicz, S. Sztuka i krytyka u nas. Warszawa,

1891.

Leon Wyczolkowski. Petrified Idol.

1894(?), oil on canvas.

152x91 cm. National Museum of Art. Warsaw

J. Czajkowski, Garden in Winter. 1900, oil on

canvas, 52,5 x 72 cm.

National Museum of Art, Cracow.

L. Wyczulkowski, Giewont at Sunrise. 1898, oil on

canvas, 101 x 159 cm.

Private collection.

F. Ruszczyc, A Winter Tale. 1904, oil on canvas,

132 x 159 cm.

National Museum of Art, Cracow.

W. Podkowinski, Cemetery. 1890–1892,

pencil on paper.

National Museum of Art, Warsaw.

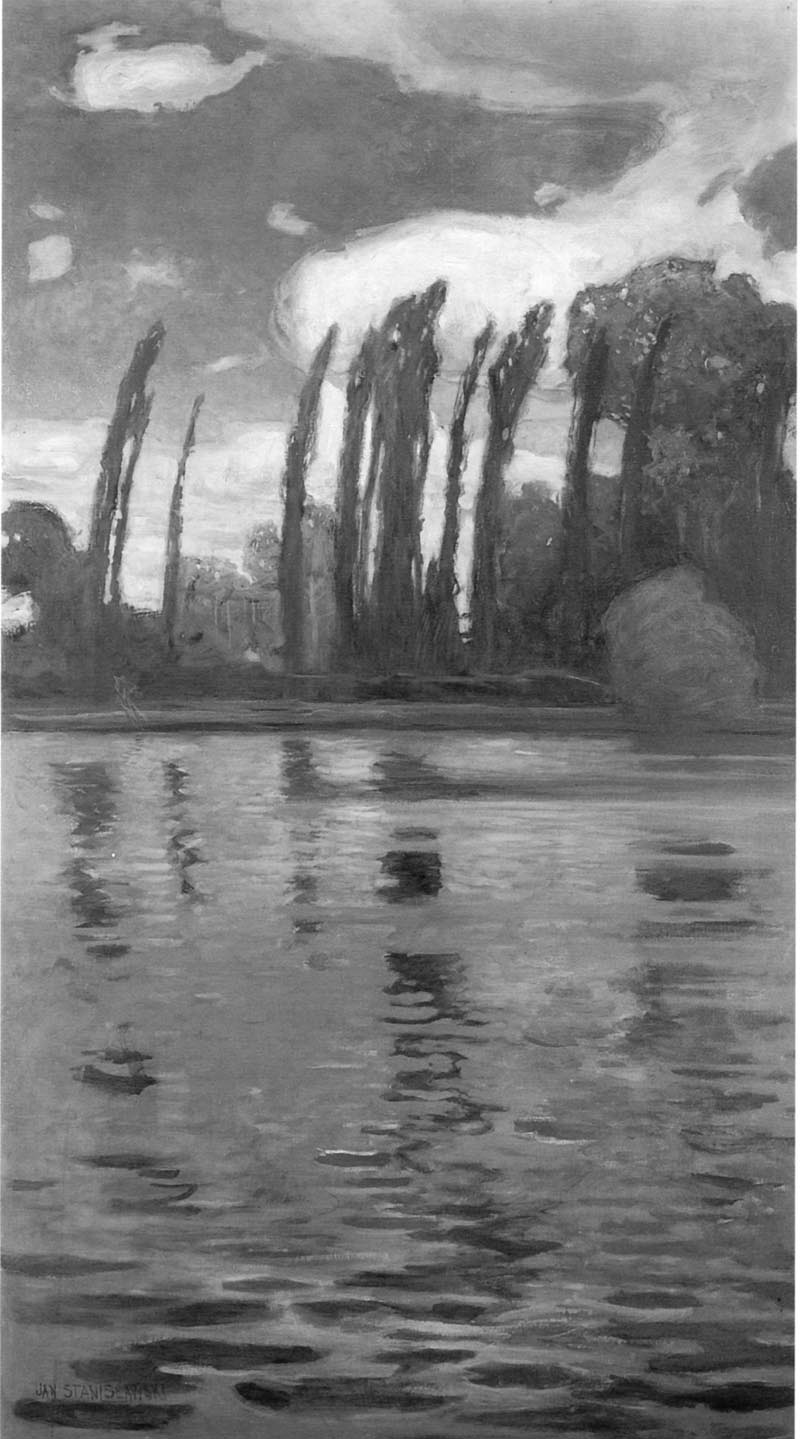

J. Stanislawski, Poplars by the Water. 1900, oil on

canvas, 145 x 80.5 cm. National Museum of Art, Cracow.

J. Stanislawski. Cloud. 1903.

National Museum of Art, Warsaw.