Copyright © 2006 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 52, No 2 - Summer 2006

Editor of this issue: Zita Kelmickaitė

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2006 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 52, No 2 - Summer 2006 Editor of this issue: Zita Kelmickaitė |

THE ARCHAIC LITHUANIAN POLYPHONIC CHANT Sutartinė

DAIVA RAČIŪNIENĖ-VYČINIENĖ

Daiva Račiūnaitė-Vyčinienė is head of the Ethnomusicology department at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theater. She has written extensively on the sutartinė, produced several CDs of Lithuanian folk music, founded a group of sutartinė singers and is the organizer of the International Folklore Festival in Vilnius.

In many countries, the Lithuanian sutartinė has become Lithuania’s “calling card” – these polyphonic chants are constantly presented to a wider audience abroad by folk music ensembles and papers read at international scholarly conferences. Nevertheless, the sutartinė is relatively unknown in the world: to many foreign listeners, they are exotica of unknown provenance that arose in a small corner of Europe – Lithuania. True, in the middle of the twentieth century, the tradition of collective chanting of the sutartinė died out from Lithuanian villages, so it doesn’t seem any less exotic to a portion of Lithuania’s inhabitants. Incidentally, this portion of inhabitants isn’t made up of younger people ignorant of tradition, but for the most part middle-aged people whose musical tastes were formed in a particular cultural context. Urban youth feel a certain intimacy with the sutartinė. For a number of contemporary people, the sutartinė has become a peculiar form of meditation; for others, it is a means of self-expression as well.

Thus, the traditional chanting of the sutartinė, now completely extinct in villages, is slowly taking root in urban folk music ensembles. The archaic Lithuanian polyphonic music style, or the socalled sutartinė, was once prevalent throughout a small area of Lithuania, the territory of northeastern Aukštaitija. The most characteristic traits of this style, uniting singing as well as instrumental musical traditions, are an abundant, frequently dominating, consonance of seconds and a complementary rhythmical structure. In spite of the originality of Lithuanian polyphonic music, some common features can also be found in the archaic polyphonic traditions of both proximate regions (the Setas region of Estonia; the Kursk, Belgorod, and Vornezh regions of Russia; Serbia; the Shopa region of Bulgaria; Albania; Aromania; Macedonia and others) and distant regions (the Pygmies in the Central African Republic; Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific, the Flores Island of Indonesia, Taiwan and many others).1

It was said of the performance of the sutartinė: “Saugimas... baisus gražumas, bet reikalau tam didelios taikos, idant sukriai ir gražiai sumušti.” 2 (The singing of the sutartinė is of great beauty, but it requires a great peace and concurrence, particularly to blend [the voices] beautifully and ingeniously.) This well-aimed remark, written by the historian Mykolas Miežinis around the year 1849, 3 testifies that the beauty of the ancient sutarinė’s sound was always dependent upon concord. Without it, neither the harmony of peoples, nor of man and his world, nor of the universe is possible. This is implicit in the name sutartinė (in dialects, sutarytė, sutartis, sutarinė, sutarytinė), derived from the verb sutarti, susitarti (to live together, to agree) or the noun sutartis (an agreement). Sutarti doesn’t just mean to agree about something or to be at peace, but also to be fitting or to match and be in harmony. So the sutartinė is a harmonious sound, or, in other words, an expression of universal harmony. Many old singers’ statements about striving for a harmonious sound while singing or blowing the panpipes or wooden horns have survived.

Perhaps because of this aim to harmonize, to agree, the sutartinė was not sung in large groups, as were many other traditional Lithuanian songs, but in smaller groups – most frequently of two, three, or four women. Despite the differing number of singers and the various styles of execution, there are almost always only two voices in the sutartinė. For this reason, the most simple and concise way of characterizing the essence of sutartinė music is to describe it as the playing of two different melodic parts at the same time. Most frequently, one musical part is vocalized in one register (that is to say, in one key or mode), and the other in another (for example, G-B and F-A-(C); D-E-F and C-D-E; etc.). As they intertwine, the melodies comprise the characteristic polytonal sound of the sutartinė; sometimes harsh (intervals of a second form between the different voice parts); sometimes playful and pulsating; less frequently, lyrical.

The interweaving of the two independent melodies is reminiscent of the process of weaving, during which the heddles dive one after another: at one moment rising up to view, at another sinking out of sight. It is this constant change that creates the multicolored cloth, too. The melody of a sutartinė sung with a meaningful text is called rinkinis (from the verb rinkti, “to collect; to select, to choose; to create”), while the refrain is called pritarinis (from the verb pritarti, “to approve, to agree with; to accompany”).

The singer singing the basic text or beginning the sutartinė is called the rinkėja, “the collector,” while the one repeating the refrain is called the pritarėja, “the accompanist”; giedotoja, “the singer,” and the like. There are many such descriptions–some of them (rinkėja, “the collector”; skaitytoja, “the reader”; sakytoja, “the speaker”; sumisliautoja, “the originator”; vadovė, “the leader”; etc.) reflect the development of the text, i.e., the creative process – others (giedotoja, “the singer”; suokėja, “the crooner”; sutartėja, “the harmonist”; patarėja, “the accompanist”; padaužėja, “the clanger”; etc.) reflect the accompaniment or its particular “framing of sound.” Sometimes, the sutartinė itself is called rinktinė. Interestingly, some of the traditional names for the sutartinė’s voice parts have corresponding weaving (plaiting) terms: there is a rinktinė sash, rinktiniai cloth or just rinkiniai (rinkinys is a patterned or multicolored cloth). In traditional thought, rinkimas is associated with the collection or creation of woven patterns, i.e., the technology of weaving patterned cloth.4 According to archaic mythological thought, all creative processes organized by strict rules, including singing, dancing, weaving, and plaiting, are perceived as a form of magic that transforms chaos into cosmic harmony. Therefore, the text of the sutartinė and the concept of the melody’s selection and harmony dovetails with a specific canonized understanding of musical “order,” that is, coherence.

The singing of the chants with an interval of a second was considered the most beautiful in folk tradition: the aim was to sumušti, “to beat, to blend”; or “sudaužyti, “to beat together” the voices as well as possible. Sometimes, the old singers compared sutartinė music to the sound of bells. It was said that “sutariant pašilėj, zvanku it varpai” (while harmonizing in the shade of the woods, it resonates like bells), “balsai susidaužia kaip zvanai” (the voices beat themselves together like bells), etc. It’s interesting that similar statements regarding polyvoice singing in seconds (that it sounds, or should sound, like bells) have been recorded by ethnomusicologists from the folksingers of various other ethnic groups in several places in Europe: Bosnia, Serbia, Bulgaria, Epyrus and elsewhere.5

Without question, the beauty of the sutartinė is unique; it is slow to reveal itself to contemporary listeners. It has been observed that the music of these chants takes hold of the listener with its somberness, its reserve, its peculiarly entrancing repetitive vocables (tūto, titity, tatatõ, kadijõ, linagõ, lingo, ritatõ, siudijõ, dūno, sadauto, siuji siujėl and other analogous words), and with the monotony of the rhythmic patterns. The listener of the sutartinė, as well as the singer, begins to be affected when it is listened to or sung for a long time. Listening to the wellsung music of an experienced group, it’s as if you yourself meld with their chants, and at the same time, it seems, with the universe, too.

Apparently, our ancestors’ knowledge and wisdom lies buried within the Lithuanian sutartinė, codified in its particular relationships of sounds, as it is in the ritual music of ancient cultures. Presumably, the first singers of the sutartinė once possessed and guarded their poetic and musical system of formulas suitable for ritual music-making, otherwise we wouldn’t be so affected by the sutartinė’s air of magic spreading from the depths of the ages. Unfortunately, the Lithuanians did not write any treatises about this ritual music nor leave such monuments of outstanding song and chant literature as the Chinese Shijing or Book of Songs, the ancient Persian Avesta, the Biblical Song of Songs, etc. The sutartinė tradition isn’t written down; it has come down to us through many generations. Nevertheless, the very structure of the sutartinė, the particulars of its performance as well as its folk terminology, reveal the once strict special rules of composition and singing.

The statements of the old singers testify to the existence of a special “secret knowledge” and a tradition of the sacred transmission of chants. For example, one singer told the nineteenth century linguist Mykolas Miežinis that their “mothers knew chants that they kept secret; they sang them only very rarely and honored their words without changing them.” 6 Keeping the chants secret and honoring words that could not be changed shows the sutartinė’s significance and sacredness. The sutartinė’s uniqueness and singularity is attested to by another statement, recorded by the famous Lithuanian expert in literature and folklore, Mykolas Biržiška:

|

Nyksta sutartinės, kurios mūsų gadynės žmonėms kartais atrodo esą slėpiningos: sutartinės [...], sako, paeiną nuo laumių arba laumaičių, kurias potam žmonės, jau būdami krikščionys, nekitaip vadino kaip raganomis. Jeigu kurios mergaitės mėgdavo jas dainuoti, tokios gaudavo ilgus metus neištekėti, nes bijodavo jaunikaičiai, idant jų pačios nebūtų raganos. 7 |

The sutartinė, which sometimes seems mysterious to the people of our age, is vanishing: the sutartinė [...], it is said, comes from fairies or sprites, which the people who came afterwards, being Christians, called witches. If girls liked to sing them, they remained unmarried for a long time, as suitors feared that they were witches themselves. |

Deeming the sutartinė singers fairies or witches (mythological beings or enchanters, sorceresses) precisely defines both the sutartinė’s essence and the status of its performers. In the second half of the twentieth century, a legend was recorded about three fairies living a few kilometers apart in the Molėtai region and singing the sutartinė.

The fact that the sutartinė is sung by fairies themselves (in Lithuanian mythology they are goddesses), leads me to surmise that this is particularly important evidence of the singularity and sacred significance of these chants. Of course, the above-mentioned stories could be considered inventions or “old wives’ tales.” According to the semiotician Algirdas Julius Greimas, however:

Even the most ridiculous-appearing thought or story has its cause and can be explained; the object of mythology isn’t the world or its artifacts, but what a human being thinks about the world, its artifacts, and himself. 8

Viewed thusly, the stories mentioned above unexpectedly reveal both of the sutartinė’s sacred sides: the positive and the negative. The first is associated with the origin of gods, with the glorification of light. The constant repetition of the vocables imparts a particular somberness and influence to the sutartinė. However, the same sound-words are enigmatic as well. It is a strange taboo, embodying the height of mystery and the invisibility of divine origin. Apparently, this innate mystery of the sutartinė determined people’s negative attitudes towards the sutartinė singers at the beginning of the twentieth century. In the understanding of that time, a witch was a woman capable of affecting people and nature by means of spells. They were to be guarded against and avoided. Therefore, the singers of the sutartinė – those enigmatic chants – as the guardians of old traditions, became themselves taboo.

It is difficult to say when the sutartinė’s “golden age” was. These chants began to be written down only at the end of the nineteenth century (except for a few examples written down at the beginning of the same century); therefore, any statements about their age can only be hypothetical. Investigators of the sutartinė do not seem to doubt their ancient origin. It is thought that their roots reach back possibly to prehistoric times, to the so-called hunter culture. There truly are many characteristics indicating the sutartinė’s ancient origin, among which could be included all of their components of syncretism: in the text: the nonstrophic text structure; the multitude of vocables or interjections; the multitextuality; the traces of patriarchal family relations and ancient trades, such as hunting and beekeeping, etc; in the choreography: walking in a circle or couples opposite couples; the dancing performed by only one sex (women); the specific steps, including hobbling or the stamping of the feet; in the particulars of the music: the narrow range of melody, the trumpet-like inflection, the lack of harmonic resolution, the syllabic relationship of the melody and the words, the complementary rhythmics, the polyphony in seconds (diaphony), heterophony, and others.

However, determining a concrete date for the origin of the sutartinė isn’t quite that simple. There is no known written documentation of their existence until the sixteenth century. The first possible mention of the sutartinė is in Maciej Stryjkovski’s “Chronicle” (1582), where attention is drawn to singers singing opposite one another with their mouths open (this specific of the sutartinė performance caught the eye of later recorders of these chants as well); it describes the singing, the constant repetition of the refrain lado, lado (similar refrains are encountered in the sutartinė); clapping (many dancing sutartinės are accompanied by clapping); and mentions the blowing of long horns (there are later records of two daudytės, long wooden trumpets, which were used to perform the sutartinė in the northern part of Aukštaitija). All the same, these descriptions by Stryjkovski and other sixteenth and seventeenth century authors are open to question – it cannot be confirmed that they are really talking about the performance of the polyphonic chants (instrumental works) that interest us here. The most credible information about the sutartinė reaches us only from the start of the twentieth century, when the priest Adolfas Sabaliauskas’s and the Finnish professor Aukusti Robert Niemi’s collection Lietuvių dainos ir giesmės šiaurrytinėje Lietuvoje (Lithuanian songs and chants in northeastern Lithuania) appeared in 1911. In 1916, the melodies for this collection were published in Lietuvių dainų ir giesmių gaidos (Melodies of Lithuanian songs and chants). The most important work about the sutartinė is held to be Zenonas Slaviūnas’s collected sutartinės in three volumes.9 Here are collected all of the sutartinės, which until then had been in various publications and manuscripts (a total of 1,820 songs, 1,000 of them with melodies). All of them, with the exception of a few chance documentations, were collected in northeast Aukštaitija. In this territory, particularly its northern section, the sutartinė was not just sung, but also played on the skudutis or panpipe; the daudytė, a long wooden trumpet; and the lamzdelis, or fife; as well as strummed on the five-string kanklės, a zither or psaltery. (The same is true for the closely related polyphonic music played on five to seven horns or a set of skudutis pipes).

The articles in Slaviūnas’s introductory tome, as well as his publication of the older singers’ commentary, show the sutartinė’s once close connection with various jobs (the harvesting of linen, rye, hay), with the family (weddings and christenings), as well as with festival rituals (Shrovetide, Whitsunday, St. John’s Day, etc.). Nevertheless, the sutartinė had already lost touch with its original surroundings a hundred years ago. Now we can only imagine the time when, according to the old singers, the fields “rang” with sutartinės:

|

Būdavo, nusiveža ažu Švenčionėlių pjaut rugių, vasarojaus, būdavo, kap išeisim–laukai žvaga šitom keturinėm... |

It used to be, they’d take us to Švenčionėliai to harvest rye and spring wheat, it used to be, when we went out, the fields rang with these foursomes... |

On the morning of a wedding, the bride and groom would be awakened with these chants:

| Keturios moterys susikabindavo ir šokdamos dainuodavo: Keliesi, martele, ir t. t. Po to jaunoji išeidavo iš svirno ir dainininkes pavaišindavo karvoliumi. | Four women would hold hands and sing while they danced: Awake, awake, daughter-in-law, and so on. After that, the bride would come out of the granary and serve the singers wedding cake. |

On harvest evenings, they would accompany the setting sun:

| Pamatį, kad saula sėda, māterys pasideda prieky savį rugių pėdų ir subeda pjautuvus pėdan. Atsigrįžį un saułį ir gieda šitų sutartinį, dėkavodamas saulai ažu dienų. Susėdį, runkas sudėjį, žiūri un saułį, linguoja priekin ir atgal, nusilinkdamos saulai, ir gieda. | Seeing that the sun was setting, the women put the sheaves of rye down in front of them and stick their sickles into the sheaves. They turn to the sun and sing this sutartinė, thanking the sun for the day. They sit, their hands folded, look at the sun, rock back and forth, bowing to the sun, and sing. |

With the connection to rituals weakening, the sutartinė began to be sung whenever, at whatever time: “Kadu užeidavā un sailās, tai ir tūtuodavām” (Whenever the urge came on, we would start tooting). Eventually, they stopped being only part of a ritual and became a unique school of vocal professionalism. As the Lithuanian ethnomusicologist Jadvyga Čiurlionytė wrote, “It isn’t easy to sing in parallel seconds – it requires continual practice. It isn’t surprising that [...] a group of sutartinė singers would associate for their entire lives and perfect their art without respite, continually searching for new means of combining their voices.” 10 Small groups of women specializing in singing sutartinės (apparently, as they themselves confirm, the sutartinė isn’t a nut that anyone can crack), for some time unwittingly continued the elite tradition of these groups of singers and guardians (perhaps in the deep past these were pagan sorcerers?)

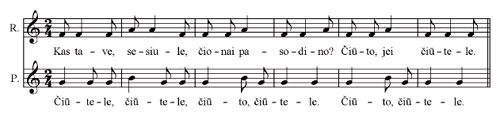

The age, robustness and richness of the tradition of singing the sutartinė is shown by the nearly forty methods of singing that still remained at the beginning of the twentieth century.11 According to the number of singers they are called dvejinė (twosomes), trejinė (threesomes), and keturinė (foursomes). These names also reflect the principles of joining voices: dvejinė and keturinė – contrapuntal, trejinė – canonal. However, whatever the number of performers, there are always only two voices – that is, two separate voice parts.

With the sutartinė retreating from the daily life of village people in the first half of the twentieth century, the mood among folklore specialists was pessimistic. In 1949, J. Čiurlionytė confirmed: “[...] young people aren’t interested in them, and that’s natural. In today’s musical culture, the sutartinė is a musical rarity. To an ear accustomed to today’s music, they seem strange [...]” 12 At the same time, some composers living and writing during that period saw the sutartinė as part of modern culture.

Edwin Geist, a German composer and musicologist of Jewish origin who lived and worked in Lithuania from 1933 to 1942, compared the sutartinė with the work of famous twentieth century modern composers, for example, Igor Stravinsky. According to Geist: “[...] the very concept of so-called atonality shows a conscious or unconscious connection with the sutartinė. Those parallel intervals of seconds and fourths are, in their harshness, just as typical of the music of today as of the sutartinė.” Geist maintains that the sutartinė represents an early type of atonal music. “In the sutartinė we can espy a precursor to the atonal direction of twentieth century art.” 13

The revival of the sutartinė began at a concert in 1969 by the Povilas Mataitis Folk Music Theater group. It was the first time sutartinė music sounded in public in a city. The concert reviewer J. Čiurlionytė wrote enthusiastically: “[...] the long-since doomed sutartinė forced its way out of the archives, emerged on the concert stage and rang out in young, attractive voices. And it became obvious that the sutartinė wasn’t an archaic relic, but a song brimming with life [...].14 Since that fateful concert, we once more hear the lively sound of the sutartinė in cities at performances of folklore ensembles. Thus, the tradition of singing the sutartinė didn’t fade out, but was reborn into a new, quantitatively different life.

For twenty years now the sutartinė rings out each year in Vilnius at the International Folklore Festival “Skamba skamba kankliai.” Special evenings are organized for the sutartinė. At this event you can see all of Vilnius’s folklore ensembles singing, dancing and playing the sutartinė with various instruments. In recent years, a space has been found that best reveals the sutartinė’s nature, embodying its sacrum. This is the fifteenth century Gothic Bernardine Church of Vilnius. These surroundings provide the opportunity for the singers to stand in a circle at the center of the shrine and allow the listeners to be immersed in the endless sound of the sutartinė’s music; that is, the uninterrupted “circle,” which I have written about many times. This positioning of the singers in a circle, or “mouth to mouth,” is necessary not just so that they can hear each other and “beat” their voices together better, but most importantly, to create a certain enclosed space, a space in which the singers become participants in the ritual of the music. As is generally recognized, the perception of rituals in various cultural traditions is similar: “Humans do it the same way gods do.” Perhaps the singers of the sutartinė continue the tradition of this kind of perception, seemingly unwittingly standing in a circle, which for people of the cosmological epoch was a symbolic guarantee of safety and comfort. The positive comments made by listeners, one of which I cite here, testify to the suitability of the Bernardine Church to the nature of the sutartinė:

As with any good work of art, there were oppositions, two poles. From the battered, pale brick altar, the large empty picture frames, the crumbling columns [...] cold emanated from the walls and floor. And there – girls, young women adorned with the traditional white wimples, young men with horns and chalumeaux. Most importantly – the most archaic Lithuanian songs and melodies, performed festively and very artistically. These two poles – the cold ruins and the bright warmth – are united by the church’s space and its exceptionally good acoustics. The onlookers here aren’t bystanders: they are extremely receptive, intently watching the action as if they were rituals [...]15

Obviously, the “Skamba skamba kankliai” evenings at the Bernardine Church cannot be the only mode of spreading the sutartinė in our modern culture. On the other hand, a yearly musical ritual of performing the sutartinė is a peculiar “tuning” of us all, a cleansing of the spirit – an idea that is attractive and worthy of support.

In recent years, the question of the preservation or extinction of authentic folklore (and consequently the sutartinė) in today’s culture has frequently been considered. It is believed that only by becoming a part of youth’s identity can the sutartinė be preserved as a part of living tradition. I agree entirely with these thoughts, however, I do not believe that the sutartinė has to become a part of popular culture, a cheap ware offered to the young in “their own musical language.” When the sutartinė lands in the pop music grinder, it speaks to the listener only in the language of pop music, and in the meantime the chants themselves are silent. You can feel this while listening to folkrock groups like “Žalvarinis” or “Atalyja.”

Relying on these examples, I would claim that the sutartinė’s modernity shouldn’t only be tied to mass culture – its integration into modern culture doesn’t have to mean the loss of its sacrum, or its transformation into profanum. There are other artistically valuable forms of spreading the sutartinė in the modern world. This could be the combination of authentic performance with visual or applied arts, pantomime, etc. The archaic incantation of the sutartinė combined with modern art should be interesting and attractive to today’s viewer. All the more since the music of the sutartinė itself (its acute harmonies, its both angular and monotonic rhythms, its minimal set of pitches), as the composers at the beginning of the twentieth century perceived, is a bridge to the modern world. Therefore the sutartinė should sound “the highest note” in today’s culture – it should become one of the most striking symbols of Lithuanian spiritual culture.

Translated by E. Novickas

An elderly group of sutartinės singers from the

village of

Smilgiai dancing.

(Photograph by Balys Biračas, 1936).

1. For more on this

subject, see Račiūnaitė-Vyčinienė, D., 2002, 55–

77.

2. “Saugimas” is the

singing of the sutartinė – the term is

apparently

from the Latvian word saukt, “to shout,

scream out loud; to sing.”

3. Slaviūnas,

1959, 1195.

4. Tumėnas, 2002.

5. Brandl, 1989,

59.

6. Русское

географическое общество, 89.

7.

Biržiška, 1921, 3.

8. Greimas, 1990,

29.

9. Slaviūnas,

1958–1959.

10. Čiurlionytė, 1969a, 126.

11. For more on this subject, see Račiūnaitė-Vyčinienė, D., Lithuanian

Polyphonic Songs. Sutartinės. Vilnius: Vaga, 2002.

12. Чюрлëните, 1949, 64.

13. Geist, 1938, 284.

14. Čiurlionytė, 1969b, 47.

15. Žukas, 1997, 48–50.

WORKS CITED

Biržiška, Mykolas. Dainos keliais.

Vilnius: Švyturys, 1921.

Brandl, R. “Die Schwebungs-Diaphonie–aus musikethnologischer und systematisch-musikwissenschaftlicher Sicht. Südosteuropa- Studien.” Band 40, Schriftenreihe der Hochschule für Musik in München. v. 9. Volks- und Kunstmusik in Südosteuropa: eds.

Eberhardt, C., and Weiss, G., Regensburg, 1989.

Čiurlionytė, Jadvyga. Lietuvių liaudies dainų melodikos bruožai. Vilnius: Vaga, 1969.

_____. “Skamba sutartinės.” Kultūros barai, 1969, No. 2.

Geist, Edwin. “Kelios pastabos ir mintys apie lietuvių liaudies dainas.” Muzikos barai, 1938, No. 11–12.

Greimas, Algirdas J. Tautos atminties beieškant. Vilnius–Chicago: Mokslas, 1990.

Русское географическое общество (The Geological Society of Russia), опиcь 1, No. 31.

Račiūnaitė-Vyčinienė, Daiva. “Lithuanian Schwebungsdiaphonie

and its South and East European Parallels.” The

World of Music.

Traditional Music in Baltic Countries [Editor Max Peter

Bauman],

vol. 44 (3), 2002. Berlin: Verlag für Wissenschaft und

Bildung.

_____. Lithuanian Polyphonic Songs. Sutartinės.

Vilnius: Vaga, 2002.

Slaviūnas, Zenonas. Sutartinės: Daugiabalsės lietuvių liaudies dainos. Vilnius, Vol. 1-2, 1958; Vol. 3, 1959.

Tumėnas, Vytautas. “Lietuvių tradicinių rinktinių juostų ornamentas. Tipologija ir semantika.” Lietuvos etnologija v. 9. Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas, 2002.

Žukas, V. “Po sutartinių skliautais.” Liaudies kultūra, 1997, No. 4.