Copyright © 2006 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 52, No 4 - Winter 2006

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2006 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 52, No 4 - Winter 2006 Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas |

La Belle Époque in Vilnius

Laima Laučkaitė

Laima Laučkaitė is a senior researcher of the Institute of Philosophy, Culture and Art, Vilnius. She holds an MA in art history from Vilnius Art Institute and a Ph.D. from Moscow University. Seventeen Rendezvous in Vilnius (Vilnius: 2005, in English, German, French, Polish and Russian) is her most recent work.

Like other cities of Central and Eastern Europe, in the early twentieth century Vilnius was a multinational city with a variety of cultures and religions. According to the 1897 census, the Jews made up 40 percent, the Poles 30.9 percent, the Russians 20.1 percent, the Belorussians 4.2 percent and the Lithuanians 2.1 percent. The predominance of the Jews can be accounted for by the fact that tsarist laws prohibited their settlement in central Russia. Thus numerous Jewish communities emerged in the towns and cities on the western fringes of the empire, especially in Vilnius. The Polish community was large, although a lot of its members identified themselves with Lithuanians rooted in the tradition of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and based on the principle gente lituanus, natione polonus. This mentality was cherished mainly by the landed Lithuanian gentry, for whom the Polish language and culture were a natural historical heritage. Meanwhile, the Lithuanian national movement produced a modern concept of the nation, one that implied that a person is a Lithuanian if he or she was born in the territory of ethnic Lithuania, spoke Lithuanian, was of peasant origin and had not experienced Polonization. The number of the representatives of this viewpoint in Vilnius at the beginning of the twentieth century was scarce, but constantly increasing. The processes of national identification and ethnic tensions were taking place in the city.

|

| Nikolai

Sergeiev-Korobov. “New Vilnius, with the Church of Saints Philip and Jacob.” 1918, oil on canvas, 105 x 71 cm, Lithuanian Art Museum. |

Following Lithuania’s annexation by Russia in the late eighteenth century, the capital of the country, Vilnius, became an ordinary provincial town, suffering from tsarist repression, persecution of the non-Russian and non-Orthodox Christian inhabitants and press censorship. The situation changed for the better only after the 1905 revolution in Russia, when Tsar Nicholas II issued a reform decree on civil liberties. In Vilnius, this liberalization was realized in various ways. National movements of all ethnic communities became legal; their aftermath was the establishment of many organizations, unions, schools, the formerly forbidden publication of periodicals and books in national languages, as well as the organization of various campaigns and events. This aspect is covered most comprehensively in the historical literature. The other aspect characteristic of early-twentieth-century Vilnius was the cultural modernization of the city and its recreational life, denoted by the term la belle époque. The present paper is devoted to this relatively unstudied subject.

In art studies, the French term la belle époque 1 refers to the period between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that ended with World War I. It was an outcome of capitalist prosperity, a period when leisure time became a way of life for the middle class and a new artistic and entertainment culture blossomed in European cities. A new urban environment arose: spacious streets, avenues, and tree-lined boulevards – with banks, hotels, large shops, and fashionable cafés – were laid out. The urban population was lured by public amusements, social gatherings, trade fairs, and fashion shows. The urban nightlife and the world of theaters, restaurants, cafésconcerts, cabarets, and vaudeville shows was suffused with the rays of the newly invented electric light. In addition, there were leisure-time activities in the open air, strolling along boulevards and through parks, picnics and outings in summer gardens, as well as gambling at racecourses.

Did Vilnius experience all of this? It might be assumed that it was not amusements that the people of Vilnius had been drawn to. They were suffering from tsarist oppression, economic backwardness and provincial conservatism, and were above all concerned with national revival. Nevertheless, la belle époque was not a prerogative of just the major European capitals.

In Vilnius, the new lifestyle mixed with the old standards and with religious festivals, especially Catholic wakes, processions and fairs. Crowds of people gathered around churches on the Feast of Saint Casimir, on Palm Sunday, and for the Way of the Cross; such festivals were accompanied by fairs. The most important spring fair was the feast of Saint Casimir, which took place in Cathedral Square and, following the building of a monument to Catherine II, was moved to Lukiškės Square. The fair was famous for ”the largest sale of homemade wood work.” Quite a large fair used to be held near the Church of Saints Peter and Paul during the Feast of St. Peter.

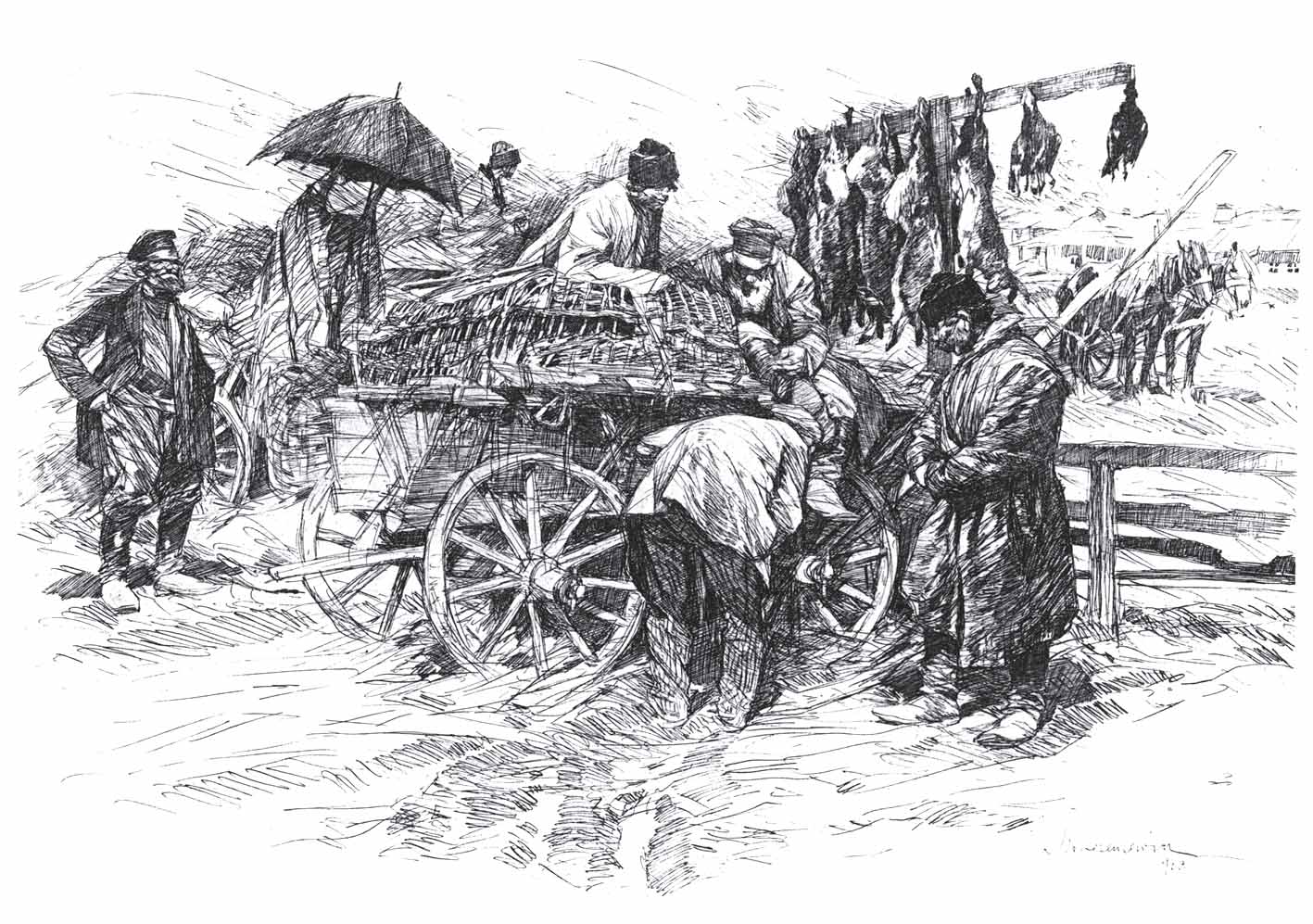

Spectacular and colorful saints’ feasts served as the favorite entertainment, although ordinary fairs, where rural elements mixed with urban types, attracted visitors as well. A masterly portrait of this side of life was revealed by the painter Stanisław Bohusz-Siestrzencewicz in his album entitled Pen-and- Ink Drawings (published in 1914). His witty and hilarious drawings are a small chronicle of Vilnius life: genre scenes of Vilnius markets, the sale of wild game, a moment of rest in an unharnessed cart, accidental flirtations, the bustle of the crowd... Bohusz-Siestrzencewicz was fascinated by the old, rural side of urban life.

|

| Stanisław Bohusz-Siestrzencewicz. “Sale of Wild Game in Vilnius.” 1903. Pen and ink drawing from Rysunki piórem (1914). |

However, another side of Vilnius existed as well – the city was modernizing. In 1903, a power station, which lit major streets, was completed, many public buildings and private houses were built and new streets laid out. St. George’s (now Gediminas) Avenue, lined with banks, cinematograph theaters, hotels, shops and a circus, was the most important among them.

The green islands of entertainment were famous – including Schumann’s restaurant with a vaudeville show and an amusement park in the Bernardine Garden and the summer residence of the Noblemen’s Club on the banks of the Vilnia River. Favorite places for strolls included the Bernardine Garden and Cielętnik at the foot of Gediminas Hill, where a town skating rink was located in winter. The city had a number of concert halls: the Hall of the City (now Philharmonic); a summer theater in the Bernardine Garden; the winter theater in the Town Hall; a hall for Jewish theater that was installed in 1909 (currently Naugardukas St. 10); Liutnia theater established in 1909 (currently Gediminas Ave. 4); the so-called Great Theatre in the house of Isaak Smaženewicz (currently Gediminas Ave. 22–24); and finally, the new Polish Theatre emerged (currently Basanavičius St.) in 1913. They showed plays staged by professional and amateur actors. These were performed in Lithuanian, Polish, Russian, Jewish and Belorussian. Many visiting troupes used to come to Vilnius. The musical life of the city was active as well – concerts were given and the symphonic orchestra, organized in 1909, became an indispensable part of Vilnius artistic culture.

The cinema appeared in Vilnius in 1902: during a fair devoted to agriculture and industry, a ”biopleograph” – views of Warsaw and Vilnius – filmed by the engineer Kazimierz Proszynski, was demonstrated in the pavilion of the Bernardine Garden.2 A boom of cinemas in the city started in 1907, with the opening of the so-called electrotheaters – Iliuzion, Szary, Parad, and Biophon. Screen presentations included views of exotic countries and simple-plot features.

The people of the city were attracted by restaurants, cafés, and K. Sztrall’s patisseries – White Sztrall in Pilies Street, Red Strall at the corner of St George’s Avenue (currently Gediminas Ave.) and Totoriai Street, and Green Sztrall in Smazenewicz’s house on St George’s Avenue – that enjoyed high popularity. Ferdynand Ruszczyc and other painters, as well as theater people and literati, met at the restaurant of St George’s Hotel (currently Gediminas Ave. 20): its architecture and interior, designed by the architect Count Tadeusz Rostworowski, were appreciated by them above all the other entertainment places in the city. In summer, the environs of the city revived. People were invited to the restaurant Riviera in Lentvaris, on the shore of a lake. Trakai and the Green Lakes were popular places for outings and picnics, both for townspeople generally and various associations.

Many recreational activities revolved around public organizations, which were abundant in the city. In the early twentieth century, there were clubs for noblemen and military officers, a city club, professional associations and other groups. After 1905, a number of national organizations were established that held parties, dances, and concerts with tableaux vivants. Especially impressive was the invasion of the Lithuanian Art Society into the cultural life of Vilnius, the artists Antanas Žmuidzinavičius, Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, and Petras Rimša organized festive vernissages, lotteries of art works, and concerts. Aristocratic society and the well-todo held parties, soirées, ”five o’clocks,” and other gatherings. Various more or less public events provided ladies with an opportunity to parade their dress and display their knowledge of high-fashion trends. It was Charles Baudelaire, a poet of contemporary life, who had already written about the modern Western artist exalting the world of beauty and fashion embodying the ideals of urban life. This keynote was reflected in the Vilnius art world as well. The recognized portraitists of prominent Vilnius citizens included the painters Bohusz-Siestrzencewicz and Ludomir Janowski, who were more concerned with reproducing good looks than psychological depth. Both were famous for their impressive representative portraits of Vilnius ladies; they also created intimate images of women’s fin-de-siècle spirit. The press wrote that Janowski should have lived in Paris for a long time and should have mixed in high society, but, in fact, he had never worked abroad. There were ladies displaying good knowledge of haute couture in Vilnius as well, and he was able to render it in his canvasses. Another type of modern woman – emancipated, educated, intellectual, and professional – is reflected in “Portrait of a Wife” painted by Antanas Žmuidzinavičius. The Lithuanian women of this type – writers, doctors, and teachers – played an important role in the national rebirth activities in Vilnius.

| Stanisław

Bohusz-Siestrzencewicz. “Vilniusite.” 1912. Tygodnik ilustrowany, 1912, No. 5. |

|

|

Antanas

Žmuidzinavičius. “Portrait of a Wife.” 1910. Oil on plywood. National M. K.Čiurlionis Museum of Art. |

The best opportunity to demonstrate garments was provided by balls and carnivals. The people of Vilnius had their traditional forms of entertainment, for example, carnival balls that were popular in nineteenth-century Vilnius, but came to be restricted by the tsarist administration after the uprising of 1863. They were revived and became an especially lively tradition following the political and cultural liberalization of 1905. Charity fund-raising carnivals took place in the halls, theaters, and hotels of the city from Christmas to Shrove Tuesday and were organized by associations and clubs. The most opulent carnivals were held at the winter hall of the Noblemen’s Club, where the whole beau monde of Vilnius was present as well as the gentry recently arrived from the provinces. A more democratic and liberal club was the one established by Vilnius bankers, uniting the Polish intelligentsia. The sets, scenery and costumes for these carnivals were in the hands of Vilnius artists. Carnivals were not just a haphazard exhibition of various masks; instead, they were thematic masquerades, in which costumes were linked together to make a scenographic whole. For example, early in 1909, a masked ball entitled In the Spider Web, with the set design by the painter Stanisław Jarocki, was held at the municipal hall; the Women’s Trusteeship Association organized a splendid dance ball Rainbow at the mansion of Countess Klementyna Tyszkiewicz, and the hall of St. George’s Hotel hummed with the colorful masquerade Butterfly.

Artists themselves used to hold parties and gatherings with music, concert programs and dances. As a way to raise funds for the organization and because of their popularity with the public, ”Saturday Gatherings” of the Vilnius Art Society were open to everyone. The public was attracted by masked balls, which members of the society prepared for in advance: in 1912, a special commission (consisting of Antanas Žmuidzinavičius, Ivan Rybakov and Ber Zalkind) was elected to coordinate such events. Echoes of Western life reached the city via the Vilnius artists studying and living abroad. In 1912, cabaret shows under such intriguing titles as Parisian Inn, A Stray Dog in the District of Montmartre, Hell, and At the Witch’s House were held. These were satirical and quite grotesque in character.

|

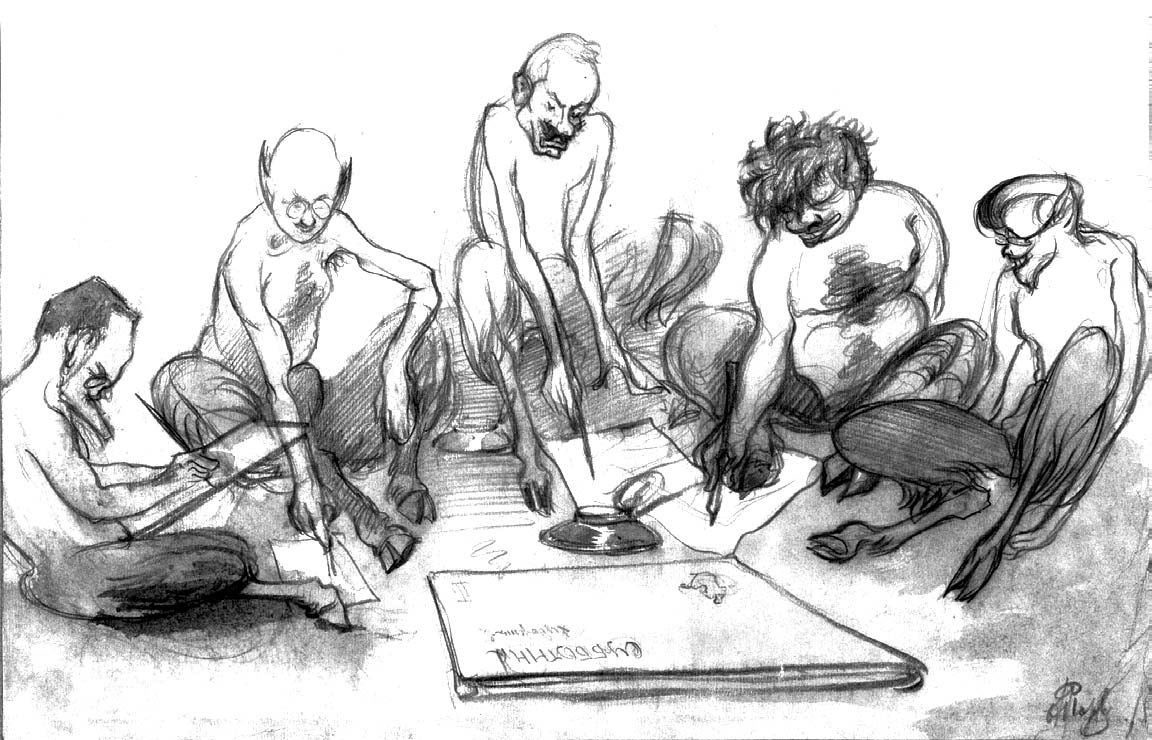

| Herman Torvirt.

Editorial Staff of the Journal “Artists’

Saturday.” 1913. Pencil, watercolor, 34.6 x 24 cm. Lithuanian Art Museum. |

Such parties were styled after cabaret shows, which were so admired in Munich and Paris in the last decade of the nineteenth century and which attracted artists, poets, musicians, actors, intellectuals and the curious well-to-do. Especially famous were the cabaret shows of Parisian bohemian artists; their pioneer was the artist Rudolf Steiner, who established the shocking cabaret Le Chat Noir 3 in Montmartre, which served as a gathering place for artists and poets, where exhibitions and balls took place, and a satirical periodical was issued. This tradition of artist gatherings was to continue through the Divan Japonais, the Lapin Agil and other cabarets. In Poland, the famous literary-artistic cabaret Zielony balonik (Green Balloon), was active in Michalik’s patisserie (known as Jama Michalika) in Cracow between 1905 and 1912 and served as a gathering place for the Young Poland poets. It was here that the humorous verse by Tadeusz Boy-Zelenski was created and the Sztuka group artists, who decorated the walls with their works, gathered; speeches were given here time and again by the Lithuanian writer Juozapas Albinas Herbačiauskas.

In the early twentieth century, cabarets started spreading in Russia. Here the best-known cabaret was The Stray Dog, which was established in St. Petersburg in 1911 by Nikolai Kulbin. A small restaurant located in the cellar served as a nightclub for artists, where they could gather to discuss the news and to improvise. Shows were given on Saturdays and Wednesdays. Especially mirthful were the Shrovetide carnivals.

Following the renovation of the premises of the Vilnius Art Society in 1913, one of the rooms, designed by painter Rybakov, was called the Bohemian Cabaret and was devoted to the parties and masquerades held by the society. In 1912, at the suggestion of Lithuanian artist Žmuidzinavičius, caricature parties were started and natural-size caricatures produced during the get-together adorned the walls of the society‘s premises. In 1913, the artists issued a manuscript satirical journal titled Subbotnik khudozhnikov (The Saturday of Artists). Only one copy of this journal (issue No 2) is preserved by the Lithuanian Art Museum: the caricatures mock the life and problems of the artists. For example, one of them tells the story of how the members of the Association pawn their wives and children after realizing that the Association‘s coffers are empty. The caricatures for the journal were produced by the artists Rybakov, Moishe Leibovski, and Zalkind. In one of the caricatures, they ironically pictured their group as antique satyrs – half-men and half-goat – preparing the material for the journal. Along with art, cartoons reflected musical events; they included caricatures of local and touring stars.

|

| Ber Zalkind. “Cartoon of Violinist Eugene Isaya.” 1913. Pencil, watercolor, 28 x 24.5 cm. Lithuanian Art Museum. |

In January 1913, the Vilnius Art Society organized a

masquerade entitled Contemporary

Artistic Trends with masks

mocking ”classics, realists, impressionists, symbolists,

pointillists,

the triangle, decadents, futurists, the donkey’s tail,

landscape painters, marine painters, painters of battle-scenes,

caricaturists, animal painters, decorators”; and in November

of

the same year, cubo-futurists were parodied during a Saturday

gathering of artists.

Lithuanians living in Vilnius started liberating themselves from a peasant mentality as well. The Rūta association was holding masked balls4 and eventually, in 1913, the first Lithuanian cabaret performance in celebration of the New Year was given. The program included humorous couplets on topical themes and national issues; the audience was especially delighted by the Chanticleer cabaret.5 These were the manifestations of a modern urban culture, the seeds of which took root in Vilnius. In addition, the Lithuanian community held salon gatherings with artists. For example, the intelligentsia and artistic society, which included Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, Ona Pleirytė-Puidienė and Liudas Gira, frequently gathered in the apartment of Julija and Antanas Smetona before World War I.

Various combined literary and artistic circles started gathering in Vilnius. Around 1909, a Polish group named Banda (Clique) was established. Its members included the writers Benedykt Hertz, a young poet Jerzy Jankowski, the painter Ferdynand Ruszczyc, as well as actors and musicians from Vilnius who aimed at rousing the city from the commonplace banality and burgher morals and tastes. The actress Maria Morozowiczowna, a member of the Banda group, wrote:

Here, in a wonderful courtyard near the Vilnia River, the parties of ours, Banda members, took place – eagerly awaited and spent dancing and singing... I danced like the barefooted Duncan, creating expressive scenes against a background of music, Jerzy Jankowski improvised, and in what an extraordinary manner! Benio (Benedykt Hertz) amused us all with his stories; Ludomir Rogowski improvised boisterously on the piano... 6

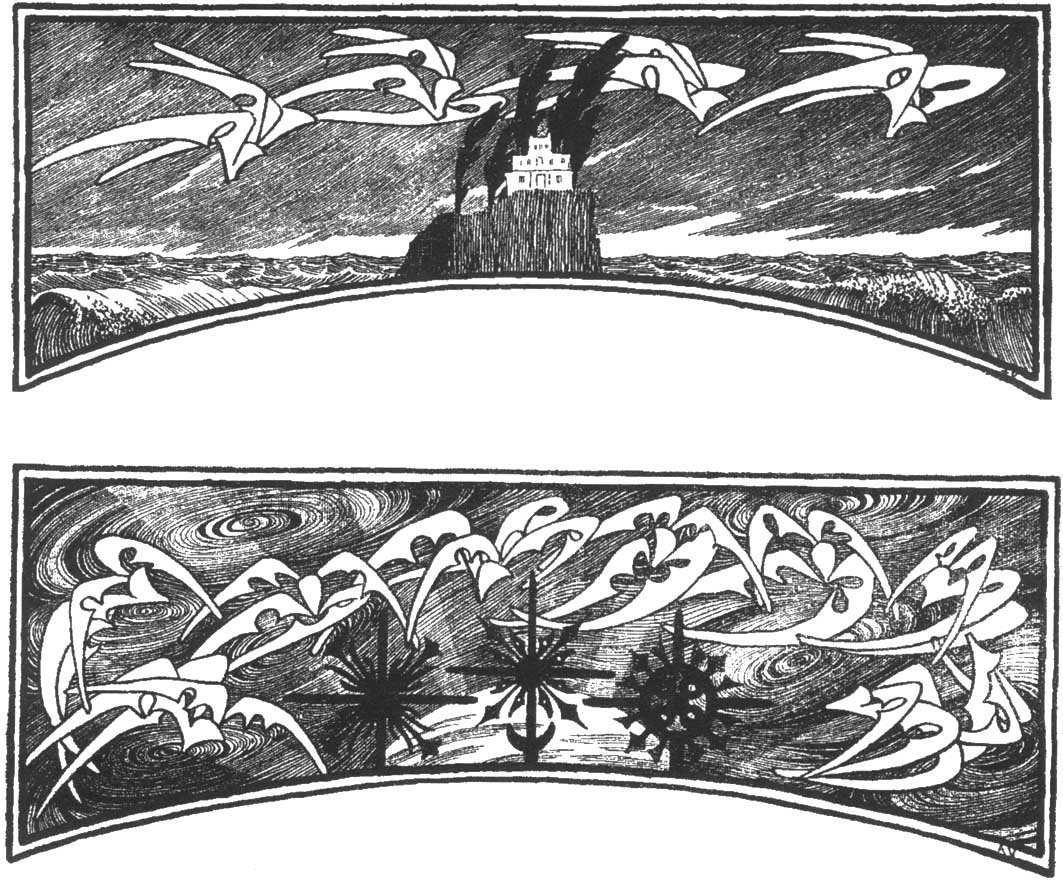

The product of their communication was Żorawce (Cranes), the finest art almanac in Vilnius in the early twentieth century designed by Ruszczyc. The Lithuanians published their own almanac Pirmasis baras, (The First Furrow), and a splendid literary magazine Vairas (The Helm), the illustrations for which were produced by the artists Adomas Varnas, Petras Rimša and Vilius Jomantas.

|

| Adomas Varnas. “Headpieces of the almanac Pirmasis baras.” 1914. |

The members of Banda included the inseparable couple of the feature writer Hertz and the composer Ludomiras Ragauskas; the former created humorous texts for songs, vaudevilles, and cabaret shows; the latter composed music. An especially famous Vilnius cabaret was Ach (Ah). Each year between 1908 and 1914, at the end of January, the cabaret presented one performance, which attracted masses of visitors and ticket prices reached incredible levels. Ach had two authors: the artist Bohusz- Siestrzencewicz staged cabarets and designed scenery and costumes, while the physician Michal Minkiewicz created humorous verses. Ach was made up of amateur singers along with professional performers: its enthusiastic participants were Lithuanian aristocrats and landowners – the Broel-Platers, the Rostworowskis, the Meysztowiczes, the Römers and others. The performances were of a non-commercial nature – the funds raised were donated to St. Anthony’s orphanage in Vilnius.

|

|

Stanisław

Bohusz-Siestrzencewicz. “Vilnius Cabaret

’Ach’”. 1911.

Tygodnik

ilustrowany, 1911,

No. 5.

|

The Ach performances combined various genres: comedy, revue, amateur theater, ballet, and satire, and addressed various current themes. For example, a performance given in 1909 depicted how stunning innovations, accompanied by the noise of cars, electric trams and aeroplanes, were encroaching on the traditional everyday life of a nobleman.7 A performance in 1911 pictured Pierre searching for his beloved (a lady with a white rose), while belles of various styles and periods as well as mechanical dolls were passing by. The poetic, lyrical spirit of the turn of the century was united in them with irony, sarcasm and phantasmagoria. “Ach is a yearly colorful and live chronicle, at the same time being a wonderful poem of lines and colours.” 8 Audiences were offered Ach publications, containing cabaret illustrations and texts, and caricatures of the spectators were drawn before each performance.

The aesthetics of the turn of the century demonstrated a special appreciation for the spirit of witticism, satire and irony. Consequently, humorous illustrated magazines gained a huge popularity in Europe. The best-known publication was Simplicissimus, which was published in Munich. Since 1904, when the tsarist prohibition of the Latin alphabet in Lithuania was revoked, a fair amount of periodicals in various languages appeared, and humorous publications became popular in Vilnius as well. Judging by their abundance (more than thirty titles), which seems surprising today, the demand for them was huge. In most cases, they were nonperiodical publications of ephemeral character: usually only several or a dozen issues were published. They contained caricatures that were very uneven in artistic quality and ranged from amateur drawings to vivid, individual stylizations. The caricatures by Bohusz-Siestrzencewicz and Adomas Varnas, which are characterized by a slender rhythm and a touch of secession style, remain unsurpassed. Examining both serious and trivial themes – from the stinging ridicule of human foibles to a parody of tense relations between nations and witty commentaries on the city news – the humorous magazines contributed to the development of the art of caricature in Vilnius in the early twentieth century.

Various forms of entertainment and witty publications became particularly numerous in the early 1910s. The closer the First World War was, the more active was the artistic and merry-making life of the city. It was a period of formation for modern urban culture, reflecting a new, capitalist way of life. The new forms of entertainment and leisure – cinematograph, cabaret, carnival, parties and matinées of various societies, art almanacs and illustrated humorous magazines – attested to the cosmopolitan nature of la belle époque. Its creators in Vilnius were artists of diverse nationalities, while the public was multiethnic and multilinguistic, consisting of Poles, Jews, Russians and Belorussians. It should be noted that the Lithuanian intelligentsia of peasant origin who actively participated in the cultural activities of Vilnius soon took on the modern urban lifestyle.

1. La Belle Epoque,

1978.

2. Romanowski, 1998, 60.

3. Counter Culture,

1999. n./a.

4. Lietuvos žinios,

1912, 3.

5. Litwa,

1913, 22.

6. Romanowski, 1999, 106.

7. Bezmenny, 1910, 3.

8. F.H. February 1910. 16.

WORKS

CITED

Bairati, Eleonora. La

Belle Epoque: Fifteen Euphoric Years of Europe History 1900-1914, New

York: William Morton & Company, 1978.

Bezmienny, ‘Ach!,’ Goniec wileński,

February 3, 1909.

Counter Culture: Parisian

Cabarets and the Avantgarde 1875–1905,

Washington: Grey Art Gallery, New York University Press, 1999.

F.H. [Franciszek Hryniewicz], ‘Ach!’, Goniec wileński,

February 16, 1910.

Litwa,

1913, 22.

Romanowski, Andrzej. Młoda

Polska wileńska, Kraków, 1999, p. 106.

_____ and Włodek, Romuald. “Kino pradžia Vilniuje (iki 1915

m.)”, Naujoji

Romuva, No. 2, 1998.

„Rūtos” kaukių balius, Lietuvos žinios,

January 12, 1912.