Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 57, No.1 - Spring 2011

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2011 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 57, No.1 - Spring 2011 Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas |

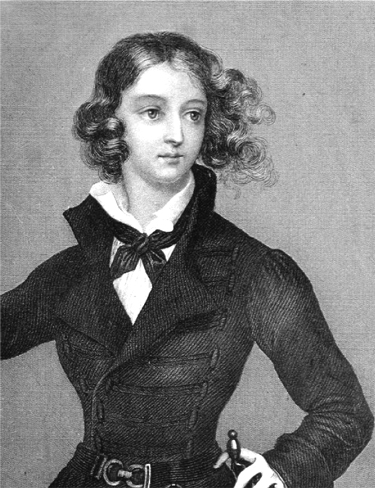

Emily Plater: ‘Frontispiece’ for Margaret Fuller’s Woman in the Nineteenth Century

PATRICK CHURA

Abstract

Margaret Fuller’s reading of Joseph Straszewicz’s

The Life

of Countess Emily Plater in 1844 apparently made a profound impression

on the American feminist-transcendentalist. In Woman in the Nineteenth

Century, Fuller included several admiring passages about Emily Plater

and suggested an portrait of the Vilnius-born countess for the

work’s frontispiece. Selecting Plater as the emblem of her

book

showed that Fuller had considered the meaning of Plater’s

life

and wanted readers of Woman in the Nineteenth Century to do the same.

Fuller’s strong response to the countess was grounded not

only on

the gender 80 barrier transgression Plater embodied as a female

military figure, but on a number of biographical details that the two

brilliant and forwardthinking women had in common. Looking at Woman in

the Nineteenth Century and The Life of Countess Emily Plater

side-by-side suggests that Straszewicz’s biography of Plater

was

a considerable influence on Fuller’s pioneering masterwork

and,

therefore, on the development of American feminist thought in its

earliest stages.

|

| Portrait of Margaret Fuller, Fuller Family Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University. |

Early in 1844, as the American transcendentalist writer Margaret Fuller was looking for material she could use to expand her ground-breaking feminist essay, “The Great Lawsuit”1 into a book-length manuscript, she came across a newly published biography of Polish-Lithuanian revolutionary Emily Plater (Emilija PliaterytŰ). A careful reading of Joseph Straszewicz’s The Life of Countess Emily Plater, translated from the French by J.K. Salomonski apparently made a profound impression on Fuller, who immediately incorporated several admiring passages about Plater into the text that became her 1845 masterwork, Woman in the Nineteenth Century.

One of the first passages Fuller added to her manuscript described Plater as an archetype of self-reliant female heroism and placed the Vilnius-born countess in a prominent honorific position:

The dignity, the purity, the concentrated resolve, the calm, deep enthusiasm, which yet could, when occasion called, sparkle up a holy, an indignant fire, make of this young maiden the figure I want for my frontispiece.2

Probably the fact that Plater's image was already in circulation - as the frontispiece of Straszewicz's widely read book - kept Fuller from actually inserting the countess's compelling portrait into her text. But the American feminist was decidedly stirred by the girl who became a captain in the First Lithuanian Infantry Regiment and a symbol of the 1829 November Uprising against imperial Russia. "Her portrait is to be seen in the book," Fuller pensively remarked, "a gentle shadow of her soul."3 Adopting the woman warrior as the emblem of her treatise showed that Fuller had not merely noticed and admired the countess's likeness; she had read Straszewicz's biography, considered the meaning of Plater's life, and decided that she wanted readers of Woman in the Nineteenth Century to do the same.

|

| J.

Penniman frontispiece to

Straszewicz’s The Life of Countess Emily Plater (1843). |

While Plater's courageous military exploits certainly impressed the American feminist, it is likely that her temperament and psychology touched Fuller just as deeply. A second important passage in Fuller's book recounts Plater's skill in dealing with jealous superior officers just before and after the decisive 1831 battles at Vilnius, Kaunas, and Siauliai. During preparations for these engagements, Plater had been advised to withdraw from her regiment, relinquish her commission, and instead take up a "grand and noble profession" more suitable to women - that of nursing the wounded. Since Fuller abhorred such patronizing sexism, she gave special attention to Plater's handling of it: "The gentle irony of her reply to these self-constituted tutors (not one of whom showed himself her equal in conduct or reason), is as good as her indignant reproof at a later period to the general, whose perfidy ruined all."4

Here Fuller alluded to two incidents that took place in Straszewicz's chapters ten and thirteen respectively. In the first, Plater rejected the argument that she was too delicate to endure the fatigues of camp life and cleverly undermined her would-be advisors. With a hint of sarcasm, Plater affirmed her resolve to remain in the fighting ranks: "Gentlemen, I am a woman, and as such, cannot overcome the curiosity which impels me to assist in your battles, and be an eye-witness of your courage; and, finally, to dress your noble wounds on the spot, at the moment you receive them." The sardonic retort disarmed her fellow officers, who "durst not oppose her views any longer."5 Of certain significance to Fuller was the fact that Plater did not reject the tasks of nursing and wound dressing - she simply pointed out that she was better able to perform them on the battlefield. Plater's implication - that blind adherence to gender-based norms and preconceptions was self-limiting to both sexes - meshed seamlessly with ideas expressed by Fuller herself, who famously asserted that "Man cannot, by right, lay even well meant restrictions on woman."6

Plater's "indignant reproof" of a faithless general, the other incident Fuller found worthy of mention, took place just after the disastrous battle at Siauliai where, despite Plater's “great courage and intrepidity,” her unit had been forced to retreat from Lithuanian territory toward the safety of Poland. When the tattered army reached the Prussian border, the commanding Polish general, Dezydery Ch¨apowski, abruptly decided to lay down his arms to seek the protection of Prussia, a power technically neutral but nevertheless “still hostile” to the Polish-Lithuanian cause. According to Straszewicz, Plater “could not bring herself to believe that all was lost beyond hope.” Refusing to countenance what she saw as the general’s disloyalty, she dared to address Ch¨apowski directly:

You have betrayed the cause of freedom and of our country, as well as of honor. I will not follow your steps into a foreign country to expose my shame to strangers. Some blood yet remains in my veins, and I have still left an arm to raise the sword against the enemy. I have a proud heart, too, which never will submit to the ignominy of treason.7

Why this episode caught Margaret Fuller’s attention as she scanned Plater’s biography is not hard to imagine. Straszewicz describes the event as a “sublime scene” in Ch¨apowski’s tent, one in which “a female, weak and timid” displayed startling bravery in challenging her military commander. The American almost certainly saw in the Polish heroine’s defiance a powerful illustration of her own then-radical demand that women be allowed to “intelligently share” in the “ideal life of their nation.” Moreover, the affair could well have been the basis for Fuller’s declaration that “persistence and courage are the most womanly no less than the most manly qualities.”8 Among the most controversial concepts in Woman in the Nineteenth Century was Fuller’s claim that “Woman can express publicly the fullness of thought and emotion, without losing any of the peculiar beauty of her sex” – a concept perhaps best exemplified in Fuller’s era by Plater.9

As these examples show, Plater’s portrait would unquestionably have made an appropriate opening image for Fuller’s revolutionary book, the first major treatise of American feminism. But the reasons for choosing Plater as a figure who somehow captured the spirit of Woman in the Nineteenth Century are neither simple nor superficial. Fuller’s visceral response to the countess was grounded not only on the barrier-transgression she embodied as a female military figure – she is often referred to as a Polish-Lithuanian Joan of Arc – but on a number of biographical details that the two brilliant and forward-thinking women had in common.

Fuller could strongly identify, for example, with the conditions of Plater’s upbringing in an environment dominated by serious study and devoid of stereotypically feminine interests. “From her earliest years,” states Straszewicz, she “evinced tastes of a very different character from those generally displayed by young persons of her age and sex.” Shunning dolls, dancing, “soft and feminine music,” and “everything which belongs to a young girl,” Plater pursued drawing, the study of history, horseback riding, and target shooting. Plater’s biographer notes that as an adolescent she “would never act like other young persons of her own sex.”10 Later, as a woman of marriageable age, she was drawn to the study of mathematics, a science thought “little suited to the female mind,” but toward which Emily herself “had exhibited a decided aptitude.”11 The culmination of Plater’s radical gender nonconformity came in 1831, when she enacted a form of gender-passing on the battlefield, assuming a masculine persona by cutting her hair and joining the nationalist army fighting for Polish-Lithuanian independence.

Like Plater, Fuller received a strenuous education far beyond the norm for young women of her time. Under the relentless instruction of her father, she learned to read and write Latin at age six, and by her early teens she was studying the most challenging works of classic literature in Greek, French, and Italian. Fuller’s precocity and intellectual seriousness isolated her socially, intimidated her classmates male and female, and left her little time or desire for pursuits believed suitable for girls. Seeking what her biographers have referred to as “intellectual perfection,” the future author of Woman in the Nineteenth Century “strove to turn herself into an intellectual person worthy of a place at her father’s side as an equal, rather than try to meet the contrary expectation... that she be an enlightened feminine lady.”12 By the time she discovered Plater, Fuller was breaking down gender barriers in her own way. In 1843, she was allowed to conduct research in the Harvard libraries, the first woman so privileged, and in 1844 she was hired by Horace Greeley to write reviews and criticism for the New York Daily Tribune, making her one of the first American women to earn a living at full-time journalism.

Despite their obvious talents, both women were sometimes scrutinized and judged disapprovingly on the basis of male-imposed standards of outward appearance rather than on their actual merits. Fuller especially was never thought beautiful and was often labeled derisively for what her transcendentalist colleague Ralph Waldo Emerson called her “extreme plainness.” In his journal, Nathaniel Hawthorne denigrated Fuller’s figure and claimed she “had not the charm of womanhood.”13 Oliver Wendell Holmes later published harsh judgments about Fuller’s looks that were clearly based in part on his notion of her as a threatening feminist: sharp-witted, over-educated, and envious of male intelligence. Even during the twentieth century, Fuller’s appearance seemed important to some. In 1957, Harvard professor Perry Miller thought it necessary to reiterate the slur that Fuller was “phenomenally homely.”14 In the opinion of one Fuller biographer, Miller was so troubled by Fuller’s refusal to adhere to traditional gender roles that he “could not forgive [her] for being ugly.”15 Recent scholarly works identify the malice of the literary establishment toward Margaret Fuller as one source for the modern “feminist as unattractive woman” caricature that persists to this day.16

“Without being perfect in beauty,” Emily Plater “was nevertheless well calculated to inspire sentiments of deep attachment; especially in a man who can value the qualities of soul and mind, more than those of the body.”17 Straszewicz’s biography repeatedly described Plater’s ability to transcend the narrow presumptions of male onlookers. One passage in particular addressed a distinction between appearance-based expectations and the actual capabilities of women:

That Fuller responded ardently to this passage is not surprising. In her several-paragraph treatment of Plater in Woman in the Nineteenth Century, she observed that “Some of the officers were disappointed at her quiet manners; that she had not the air and tone of a stage-heroine. They thought she could not have acted heroically unless in buskins; [they] had no idea that such deeds only showed the habit of her mind.”19 Fuller was clearly intrigued by Plater’s triumph over chauvinism, a triumph based on the notion that although there was admittedly “nothing very striking in her person at first sight,” Plater’s courage and achievement were nevertheless recognized and celebrated.20 What the American feminist seems amazed by is that Plater had found a biographer who understood her – who was able to penetrate an exterior that did not suggest heroism in order to describe the real person who did. In her famous book, Fuller wistfully wrote: “But though, to the mass of these men, she was an embarrassment and a puzzle, the nobler sort viewed her with a tender enthusiasm worthy of her.” Paraphrasing from Straszewicz, Fuller rejoiced that “Her name... is known throughout Europe” and announced, “I paint her character that she may be as widely loved.”21

Assessing the plight of women in her time, Fuller declared confidently, perhaps with Plater in mind, that “the restraints upon the sex were insuperable only to those who think them so.”22 Surely the most legendary line in Woman in the Nineteenth Century is Fuller’s oft-repeated rejoinder to the question of what “offices” women may fill: “Let them be sea-captains, if you will.”23 Among the several historical figures mentioned with this passage as examples of “women well-fitted for such an office,” Plater is the only one who was a nineteenth-century contemporary of Fuller.

In a letter to her friend Caroline Sturgis written just after the publication of Woman in the Nineteenth Century, Fuller divulged that her public praise for the woman she referred to as “Countess Colonel Plater” had become controversial, garnering attention and disapproval in the popular press. After informing Sturgis where in Boston she could buy a copy of the “Memoir” about Plater, Fuller wrote, “The newspaper editors, who have not read the Memoir, are more indignant at my praise of Emily than at any of my other sins. They say it is evident that I would like to be a Colonel Plater!”24 This interesting disclosure affirms not only that the editors in question considered the Polish-Lithuanian rebel girl to be Fuller’s inspiration, but that Plater, who died in 1831 at the age of twenty-six, worried defenders of the American status quo as much as Fuller did. And while the antagonism of the press toward Fuller was reactionary and anti-feminist, its basic premise was accurate: Margaret Fuller did wish, on some level, to “be” an Emily Plater.

Three months after her letter to Sturgis, Fuller wrote to another close friend, Sarah Shaw, congratulating her on the birth of a daughter. “Heaven... must have some important task before us women, it sends us so many little girls,” she mused, opening the way to serious reflection about gender politics. At the close of the letter, Fuller informed Mrs. Shaw that an alternate use had been found for the image she had wanted as her book’s frontispiece. Alongside the “little crucifix” hanging on the wall above her writing table, Fuller explained, she had placed “a picture of Countess Emily Plater.”25

In a way, a portrait of the countess did appear in Fuller’s book, if only in the form of the American author’s sensitive internalization of Plater’s heroic model. As Robert Hudspeth recently observed, “Fuller found much of her own personality reflected in Plater.”26 Tragically, the epitaph for the “countess colonel” found in Woman in the Nineteenth Century could apply as well to Fuller, who died at the age of forty in a shipwreck off New York’s Fire Island: “Short was her career. Like the Maid of Orleans, she only did enough to verify her credentials, and then passed from a scene on which she was, probably, a premature apparition.”27

Looking at Woman in the Nineteenth Century and The Life of Countess Emily Plater side-by-side suggests a Fuller-Plater bond that is deep and significant. It also offers ample evidence that Straszewicz’s biography of Plater was a considerable influence on Fuller’s pioneering masterwork, and therefore on the development of American feminist thought in its earliest stages.

WORKS CITED

Fuller, Margaret. Woman in the Nineteenth Century 1845, rpt. 1999, New York: Dover Publications.

Hawthorne, Julian. Nathaniel Hawthorne and His Wife: A Biography 1884; rpt., Michigan State University Press, 1968.

Hudspeth, Robert N., ed. The Letters of Margaret Fuller, Vol. IV, 1845-1847. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1987.

McGavran Murray, Meg. Margaret Fuller, Wandering Pilgrim. Athens,Georgia and London: University of Georgia Press, 2008.

Miller, Perry. “I Find No Intellect Comparable to My Own,” American Heritage 8 (February 1957).

Straszewicz, Joseph. The Life of Countess Emily Plater. tr. J. K. Salomonski. New York: James Linen, 1843.